Sample space

| Probability theory |

|---|

|

In probability theory, the sample space of an experiment or random trial is the set of all possible outcomes or results of that experiment.[1] A sample space is usually denoted using set notation, and the possible outcomes are listed as elements in the set. It is common to refer to a sample space by the labels S, Ω, or U (for "universal set").

For example, if the experiment is tossing a coin, the sample space is typically the set {head, tail}. For tossing two coins, the corresponding sample space would be {(head,head), (head,tail), (tail,head), (tail,tail)}. For tossing a single six-sided die, the typical sample space is {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6} (in which the result of interest is the number of pips facing up).[2]

A well-defined sample space is one of three basic elements in a probabilistic model (a probability space); the other two are a well-defined set of possible events (a sigma-algebra) and a probability assigned to each event (a probability measure function).

Multiple sample spaces

For many experiments, there may be more than one plausible sample space available, depending on what result is of interest to the experimenter. For example, when drawing a card from a standard deck of fifty-two playing cards, one possibility for the sample space could be the various ranks (Ace through King), while another could be the suits (clubs, diamonds, hearts, or spades).[1][3] A more complete description of outcomes, however, could specify both the denomination and the suit, and a sample space describing each individual card can be constructed as the Cartesian product of the two sample spaces noted above (this space would contain fifty-two equally likely outcomes). Still other sample spaces are possible, such as {right-side up, up-side down} if some cards have been flipped in shuffling.

Equally likely outcomes

In some sample spaces, it is reasonable to estimate or assume that all outcomes in the space are equally likely (that they occur with equal probability). For example, when tossing an ordinary coin, one typically assumes that the outcomes "head" and "tail" are equally likely to occur. An implicit assumption that all outcomes in the sample space are equally likely underpins most randomization tools used in common games of chance (e.g. rolling dice, shuffling cards, spinning tops or wheels, drawing lots, etc.). Of course, players in such games can try to cheat by subtly introducing systematic deviations from equal likelihood (e.g. with marked cards, loaded or shaved dice, and other methods).

Some treatments of probability assume that the various outcomes of an experiment are always defined so as to be equally likely.[4] However, there are experiments that are not easily described by a sample space of equally likely outcomes— for example, if one were to toss a thumb tack many times and observe whether it landed with its point upward or downward, there is no symmetry to suggest that the two outcomes should be equally likely.

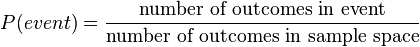

Though most random phenomena do not have equally likely outcomes, it can be helpful to define a sample space in such a way that outcomes are at least approximately equally likely, since this condition significantly simplifies the computation of probabilities for events within the sample space. If each individual outcome occurs with the same probability, then the probability of any event becomes simply:[5]:346-347

Simple random sample

In statistics, inferences are made about characteristics of a population by studying a sample of that population's individuals. In order to arrive at a sample that presents an unbiased estimate of the true characteristics of the population, statisticians often seek to study a simple random sample— that is, a sample in which every individual in the population is equally likely to be included.[5]:274-275 The result of this is that every possible combination of individuals who could be chosen for the sample is also equally likely (that is, the space of simple random samples of a given size from a given population is composed of equally likely outcomes).

Infinitely large sample spaces

In an elementary approach to probability, any subset of the sample space is usually called an event. However, this gives rise to problems when the sample space is infinite, so that a more precise definition of an event is necessary. Under this definition only measurable subsets of the sample space, constituting a σ-algebra over the sample space itself, are considered events. However, this has essentially only theoretical significance, since in general the σ-algebra can always be defined to include all subsets of interest in applications.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Albert, Jim (21 January 1998). "Listing All Possible Outcomes (The Sample Space)". Bowling Green State University. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ↑ Larsen, R. J.; Marx, M. L. (2001). An Introduction to Mathematical Statistics and Its Applications (Third ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 22. ISBN 9780139223037.

- ↑ Jones, James (1996). "Stats: Introduction to Probability - Sample Spaces". Richland Community College. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ↑ Foerster, Paul A. (2006). Algebra and Trigonometry: Functions and Applications, Teacher's Edition (Classics ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 633. ISBN 0-13-165711-9.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Yates, Daniel S.; Moore, David S; Starnes, Daren S. (2003). The Practice of Statistics (2nd ed.). New York: Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-4773-4.