Sami languages

| Sami | |

|---|---|

| Lappish | |

| Saami | |

| Native to | Finland, Norway, Russia, and Sweden |

| Region | Sápmi (Lapland) |

| Ethnicity | Sami people |

Native speakers | 20,000–25,000 (ca. 1992)[1] |

|

Uralic

| |

Early forms |

Proto-Samic

|

| Official status | |

Official language in | Sweden and some parts of Norway; recognized as a minority language in several municipalities of Finland. |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

Variously: sia – Akkala sjd – Kildin sjk – Kemi sjt – Ter smn – Inari sms – Skolt sju – Ume sje – Pite sme – Northern smj – Lule sma – Southern |

Historically verified distribution of the Sami languages: 1. Southern Sami, 2. Ume Sami, 3. Pite Sami, 4. Lule Sami, 5. Northern Sami, 6. Skolt Sami, 7. Inari Sami, 8. Kildin Sami, 9. Ter Sami. Darkened area represents municipalities that recognize Sami as an official language. | |

Sami /ˈsɑːmi/[2] is a group of Uralic languages spoken by the Sami people in Northern Europe (in parts of northern Finland, Norway, Sweden and extreme northwestern Russia). Sami is frequently and erroneously believed to be a single language. Several names are used for the Sami languages: Saami, Sámi, Saame, Samic, Saamic, as well as the exonyms Lappish and Lappic. The last two, along with the term Lapp, are now often considered derogatory.[3]

Classification

The Sami languages form a branch of the Uralic language family. According to the traditional view, Sami is within the Uralic family most closely related to the Finnic languages (Sammallahti 1998). However, this view has recently been doubted by some scholars, who argue that the traditional view of a common Finno-Sami protolanguage is not as strongly supported as has been earlier assumed,[4] and that the similarities may stem from an areal influence on Sami from Finnic.

In terms of internal relationships, the Sami languages are divided into two groups: western and eastern. The groups may be further divided into various subgroups and ultimately individual languages. (Sammallahti 1998: 6-38.) Parts of the Sami language area form a dialect continuum in which the neighbouring languages may be mutually intelligible to a fair degree, but two more widely separated groups will not understand each other's speech. There are, however, some sharp language boundaries, in particular between Northern Sami, Inari Sami and Skolt Sami, the speakers of which are not able to understand each other without learning or long practice. The evolution of sharp language boundaries seems to suggest a relative isolation of the language speakers from each other and not very intensive contacts between the respective speakers in the past. There is some significance in this, as the geographical barriers between the respective speakers are no different from those in other parts of the Sami area.

Western Sami languages

- Southwestern

- Southern Sami (600)[5]

- Åsele dialect

- Jämtland dialect

- Ume Sami (20)[6]

- Southern Sami (600)[5]

- Northwestern

Eastern Sami languages

- Mainland

- Inari Sami (300)[10]

- Kemi Sami (extinct)

- Skolt Sami (420)[11]

- Akkala Sami (extinct)

- Peninsular

- Kildin Sami (500)[12]

- Ter Sami (2[13]-10[14])

Note that the above figures are approximate.

Geographic distribution

The Sami languages are spoken in Sápmi in Northern Europe, in a region stretching over the four countries Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia, reaching from the southern part of central Scandinavia in the southwest to the tip of the Kola Peninsula in the east. The border between the languages does not follow the political borders.

During the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age now extinct Sami languages were also spoken in the central and southern parts of Finland and Karelia and in a wider area on the Scandinavian peninsula. Historical documents as well as Finnish and Karelian oral tradition contain many mentions of the earlier Sami inhabitation in these areas (Itkonen 1947). Also loanwords as well as place-names of Sami origin in the southern dialects of Finnish and Karelian dialects testify of earlier Sami presence in the area (Koponen 1996; Saarikivi 2004; Aikio 2007). These Sami languages, however, became extinct later, under the wave of the Finno-Karelian agricultural expansion.

History

The Proto-Samic language is believed to have formed in the vicinity of the Gulf of Finland between 1000 BCE to 700 CE deriving from a common Proto-Sami-Finnic language (M. Korhonen 1981).[15] However reconstruction of any basic proto-languages in the Uralic family have reached a level close to or identical to Proto-Uralic (Salminen 1999).[16] According to the comparative linguist Ante Aikio, the Proto-Samic language developed in South Finland or in Karelia around 2000–2500 years ago, spreading then to northern Fennoscandia.[17] The language is believed to have expanded west and north into Fennoscandia during the Iron Age reaching central-Scandinavia during the Proto-Scandinavian period (Bergsland 1996).[18] The language assimilated several layers of unknown Paleo-European languages from the early hunter gatherers, first during the Proto-Sami phase and second in the subsequent expansion of the language in the west and the north of Fennoscandia that is part of modern Sami today. (Aikio 2004, Aikio 2006).[19][20]

Written languages and sociolinguistic situation

At present there are nine living Sami languages. The largest six of the languages have independent literary languages; the three others have no written standard, and of them, there are only few, mainly elderly speakers left. The ISO 639-2 code for all Sami languages without its proper code is "smi". The six written languages are:

- Northern Sami (Norway, Sweden, Finland): With an estimated 15,000 speakers, this accounts for probably more than 75% of all Sami speakers in 2002.[citation needed] ISO 639-1/ISO 639-2: se/sme

- Lule Sami (Norway, Sweden): The second largest group with an estimated 1,500 speakers.[citation needed] ISO 639-2: smj

- Southern Sami (Norway, Sweden): 500 speakers (estimated).[citation needed] ISO 639-2: sma

- Inari Sami (Enare Sami) (Inari, Finland): 500 speakers (estimated).[citation needed] SIL code: LPI, ISO 639-2: smn

- Skolt Sami (Näätämö and the Nellim-Keväjärvi districts, Inari municipality, Finland, also spoken in Russia, previously in Norway): 400 speakers (estimated).[citation needed] SIL code: LPK, ISO 639-2: sms

- Kildin Sami (Kola Peninsula, Russia): 608 speakers in Murmansk Oblast, 179 in other Russian regions, although 1991 persons stated their Saami ethnicity (1769 of them live in Murmansk Oblast)[21] SIL code: LPD

The other Sami languages are critically endangered or moribund and have very few speakers left. Pite Sami has about 30–50 speakers,[22] and a dictionary and an official orthography is under way. Ume Sami likely has under 20 speakers left,[citation needed] and ten speakers of Ter Sami were known to be alive in 2004.[23] The last speaker of Akkala Sami is known to have died in December 2003,[24] and the eleventh attested variety, Kemi Sami, became extinct in the 19th century.

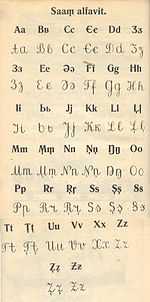

Orthographies

The Sami languages use Latin alphabets.

Northern Sami: Áá Čč Đđ Ŋŋ Šš Ŧŧ Žž Inari Sami: Áá Ââ Ää Čč Đđ Šš Žž Skolt Sami: Ââ Čč Ʒʒ Ǯǯ Đđ Ǧǧ Ǥǥ Ǩǩ Ŋŋ Õõ Šš Žž Åå Ää (+soft sign ´) Lule Sami in Sweden: Áá Åå Ńń Ää Lule Sami in Norway: Áá Åå Ńń Ææ Southern Sami in Sweden: Ïï Ää Öö Åå Southern Sami in Norway: Ïï Ææ Øø Åå

Note that the letter Đ is a capital D with a bar across it (Unicode U+0110) also used in Serbo-Croatian etc., and is not the capital eth (Ð; U+00D0) found in Icelandic, Faroese or Old English, to which it is almost identical.

Note also that the different characters used on the different sides of the Swedish/Norwegian border merely are orthographic standards based on the Swedish and Norwegian alphabet, respectively, and don't denote different pronunciations.

Kildin Sami now uses an extended version of Cyrillic (in three slightly different variants): аА а̄А̄ ӓӒ бБ вВ гГ дД еЕ е̄Е̄ ёЁ ё̄Ё̄ жЖ зЗ һҺ/ʼ иИ ӣӢ йЙ јЈ/ҋҊ кК лЛ ӆӅ мМ ӎӍ нН ӊӉ ӈӇ оО о̄О̄ пП рР ҏҎ сС тТ уУ ӯӮ фФ хХ цЦ чЧ шШ (щЩ) ъЬ ыЫ ьЬ ҍҌ эЭ э̄Э̄ ӭӬ юЮ ю̄Ю̄ яЯ я̄Я̄

Skolt Sami uses ˊ (U+02CA) as a soft sign; due to technical restrictions, it is often replaced by ´ (U+00B4).

Official status

Norway

Adopted in April 1988, Article 110a of the Norwegian Constitution states: "It is the responsibility of the authorities of the State to create conditions enabling the Sami people to preserve and develop its language, culture and way of life". The Sami Language Act went into effect in the 1990s. Sami is an official language of the municipalities of Kautokeino, Karasjok, Gáivuotna (Kåfjord), Nesseby, Porsanger, Tana, Tysfjord, Lavangen and Snåsa.

Finland

In Finland, the Sami language act of 1991 granted Sami people the right to use the Sami languages for all government services. Three Sami languages are recognized: Northern, Skolt and Inari Sami. The Sami language act of 2003 made Sami an official language in Enontekiö, Inari, Sodankylä and Utsjoki municipalities.

Sweden

On 1 April 2002, Sami became one of five recognized minority languages in Sweden. It can be used in dealing with public authorities in the municipalities of Arjeplog, Gällivare, Jokkmokk and Kiruna. In 2011 this list was enlarged considerably. In Sweden the Umeå and Uppsala Universities have courses in North Sami, and Umeå University has also Ume Sami and South Sami.

Russia

In Russia, Sami has no official status. Sami has been taught at the Murmansk University since 2012; before then, Sami was taught at the Institutе of Peoples of the North (Институт народов севера) in Saint Petersburg (Leningrad).

See also

- Sami parliaments of Finland, Norway, and Sweden

References

- ↑ Akkala reference at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

Kildin reference at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

Kemi reference at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

Ter reference at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

Inari reference at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

Skolt reference at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

(Additional references under 'Language codes' in the information box) - ↑ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- ↑ Karlsson, Fred (2008). An Essential Finnish Grammar. Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-415-43914-5.

- ↑ T. Salminen: Problems in the taxonomy of the Uralic languages in the light of modern comparative studies. — Лингвистический беспредел: сборник статей к 70-летию А. И. Кузнецовой. Москва: Издательство Московского университета, 2002. 44–55. AND

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Southern Sami

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Ume Sami

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Pite Sami

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Lule Sami

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Northern Sami

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Inari Sami

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Skolt Sami

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Kildin Sami

- ↑ Pravda - The 5 Smallest Languages of the World

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Ter Sami

- ↑ Korhonen, Mikko 1981: Johdatus lapin kielen historiaan. Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seuran toimituksia ; 370. Helsinki, 1981

- ↑

- Problems in the taxonomy of the Uralic languages in the light of modern comparative studies. — Лингвистический беспредел: сборник статей к 70-летию А. И. Кузнецовой. Москва: Издательство Московского университета, 2002. 44–55.

- ↑ Aikio, Ante (2004), "An essay on substrate studies and the origin of Saami", in Hyvärinen, Irma; Kallio, Petri; Korhonen, Jarmo, Etymologie, Entlehnungen und Entwicklungen: Festschrift für Jorma Koivulehto zum 70. Geburtstag, Mémoires de la Société Néophilologique de Helsinki 63, Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, pp. 5–34

- ↑ Knut Bergsland: Bidrag til sydsamenes historie, Senter for Samiske Studier Universitet i Tromsø 1996

- ↑ Aikio, A. (2004). An essay on substrate studies and the origin of Saami. Irma Hyvärinen / Petri Kallio / Jarmo Korhonen (eds.), Etymologie, Entlehnungen und Entwicklungen: Festschrift für Jorma Koivulehto zum 70. Geburtstag, pp. 5–34. Mémoires de la Société Néophilologique de Helsinki 63. Helsinki.

- ↑ Aikio, A. (2006). On Germanic-Saami contacts and Saami prehistory. Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 91: 9–55..

- ↑ Russian Census (2002). Data from http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_nac_02.php?reg=0

- ↑ According to researcher Joshua Wilbur and Pite Sami dictionary committee leader Nils Henrik Bengtsson, March 2010.

- ↑ Tiuraniemi Olli: "Anatoli Zaharov on maapallon ainoa turjansaamea puhuva mies", Kide 6 / 2004.

- ↑ Microsoft Word - Nordisk samekonvensjon hele dokumentet 14112005.doc

- General

- Fernandez, J. 1997. Parlons lapon. - Paris.

- Itkonen, T. I. 1947. Lapparnas förekomst i Finland. - Ymer: 43–57. Stockholm.

- Koponen, Eino 1996. Lappische Lehnwörter im Finnischen und Karelischen. - Lars Gunnar Larsson (ed.), Lapponica et Uralica. 100 Jahre finnisch-ugrischer Unterricht an der Universität Uppsala. Studia Uralica Uppsaliensia 26: 83-98.

- Saarikivi, Janne 2004. Über das saamische Substratnamengut in Nordrußland und Finnland. - Finnisch-ugrische Forschungen 58: 162–234. Helsinki: Société Finno-Ougrienne.

- Sammallahti, Pekka (1998). The Saami Languages: an introduction. Kárášjohka: Davvi Girji OS. ISBN 82-7374-398-5.

External links

| Northern Sami edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Sami languages test of Southern Sami language at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Sami languages test of Kildin Sami language at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Sami languages test of Ter Sami language at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Sami languages test of Inari Sami language at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Sami languages test of Lule Sami language at Wikimedia Incubator |

- Ođđasat TV Channel in Sami languages

- On line radio stream in various sami languages

- Introduction to the history and current state of Sami

- Kimberli Mäkäräinen "Sámi-related odds and ends," including 5000+ word vocabulary list

- Risten Sámi dictionary and terminology database.

- Giellatekno Morphological and syntactic analysers and lexical resources for several Sami languages

- Divvun Proofing tools for some of the Sami languages

- Sámedikki giellastivra - Sami language department of the Norwegian Sami parliament (in Norwegian and Northern Sami)

- Finland - Sámi Language Act

- Sami Language Resources All about Sami Languages with glossaries, scholarly articles, resources

- Álgu database, an etymological database of the Sami languages (in Finnish and North Sámi)

- Sami anthems, Sami anthems in various Sami languages

- , The Internationale in Northern Sami

- An extensive intro to Saami languages and grammar from How To Learn Any Language

- Sámi dieđalaš áigečála the only peer-reviewed journal in Saami languages

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||