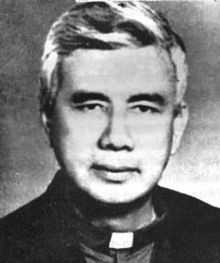

Rutilio Grande

Rutilio Grande García, S.J. (5 July 1928, El Paisnal - 12 March 1977, Aguilares) was a Jesuit priest in El Salvador and a promoter of liberation theology. He was assassinated in 1977, along with two other Salvadorans. Rutilio Grande was the first priest assassinated before the civil war started. He was a close friend of Archbishop Óscar Arnulfo Romero. After his death, the Archbishop changed his conservative attitude toward the government and urged the government to investigate the murder.

Life and work

Grande was recruited into the priesthood by Archbishop Luis Chávez y González. Grande was trained at the seminary of San José de la Montaña, where he became friends with Romero, a fellow student. Grande was ordained a priest in 1959, and went on to study abroad, mainly in Spain.[1] He returned to El Salvador in 1965 and was appointed director of social action projects at the seminary in San Salvador, a position he held for nine years.[2] From 1965 to 1970 he was also prefect of discipline and professor of pastoral theology in the diocesan seminary.[3] Grande was master of ceremonies at Romero’s installation as bishop of Santiago de María in 1975.[4]

He began to serve in the parish of Aguilares in 1972. Grande was responsible, along with many other Jesuits, for establishing Christian base communities (CEBs, in Spanish) and training Delegates of the Word to lead them.[5] Local landowners saw the organization of the peasants as a threat to their power.

Father Grande also challenged the government in its response to actions he saw as attempts to harass and silence Salvadoran priests. Father Mario Bernal Londono, a Colombian priest serving in El Salvador, had been kidnapped January 28, 1977 — allegedly by guerrillas — in front of the Apopa church near San Salvador, together with a parishioner who was safely released.[6] He later was cast out of the country by the Salvadoran government. On February 13, 1977, Grande preached a sermon that came to be called "the Apopa sermon," denouncing the government's expulsion of Father Bernal, an action that some later believed helped to provoke Grande's murder:

- I am fully aware that very soon the Bible and the Gospels will not be allowed to cross the border. All that will reach us will be the covers, since all the pages are subversive—against sin, it is said. So that if Jesus crosses the border at Chalatenango, they will not allow him to enter. They would accuse him, the man-God ... of being an agitator, of being a Jewish foreigner, who confuses the people with exotic and foreign ideas, anti-democratic ideas, and i.e., against the minorities. Ideas against God, because this is a clan of Cain’s. Brothers, they would undoubtedly crucify him again. And they have said so.[7]

Death and aftermath

On Saturday, March 12, 1977, the priest, accompanied by Manuel Solorzano, 72, and Nelson Rutilio Lemus, 16, was driving through the sugar fields near the village of El Paisnal in the Aguilares parish on their way to evening Mass, when all three were slaughtered by machine gun fire.[7][8]

Upon learning of the murders, the archbishop went to the church where the three bodies had been laid and celebrated Mass. Afterward, he spent hours listening to stories of suffering local peasant farmers, and hours in prayer. The next morning, after meeting with his priests and advisers, Romero announced that he would not attend any state occasions nor meet with the president — both traditional activities for his longtime predecessor — until the death was investigated. As no investigation ever was conducted, this decision meant that Romero attended no state occasions whatsoever in his three years as Archbishop.[9]

On Monday, March 14, 1977, the Archbishop's office published a bulletin specifically directed at refuting claims made in the two major national newspapers, El Diario de Hoy and La Prensa Gráfica. The bulletin denied assertions in the papers repeating official claims by a medical examiner as to the bodies of the three men, and also put forth a detailed account of Romero's views on the murders:

- The true reason for [Grande's] death was his prophetic and pastoral efforts to raise the consciousness of the people throughout his parish. Father Grande, without offending and forcing himself upon his flock in the practice of their religion, was only slowly forming a genuine community of faith, hope and love among them, he was making them aware of their dignity as individuals, of their basic rights as words, his was an effort toward comprehensive human development. This post-Vatican Council ecclesiastical effort is certainly not agreeable to everyone, because it awakens the consciousness of the people. It is work that disturbs many; and to end it, it was necessary to liquidate its proponent. In our case, Father Rutilio Grande.[7]

The following Sunday, in protest of the killings of Grande and his companions, newly appointed Archbishop Romero canceled Masses throughout the archdiocese, in favor of one single Mass in the cathedral in San Salvador. The move drew criticism from church officials, but more than 150 priests joined the Mass as celebrants and over 100,000 people came to the cathedral to hear Romero's address, which called for an end to the violence.[9][10]

The film biography Romero (1989) depicts Grande's friendship with Romero, his community work and activism, and his assassination. (Grande was played by American actor Richard Jordan.) In the film, Grande's death becomes a major motivation in Romero's shift toward an activist role within the church and the nation. This view is supported in various biographies of Romero.[9][11]

Since 1977

- On March 15, 1991, a group of Salvadorans returning from Nicaragua after 11 years of being refugees founded Comunidad Rutilio Grande. Among the group's many projects is "Radio Rutilio," a radio station featuring local youth as broadcasters of community news and announcements.[12] The community also participates in a partnership with a Lutheran congregation in the United States to provide secondary education to children in the Rutilio Grande community.[13] In addition, the community has also maintained a sister city relationship with the town of Davis, California since 1996.[14]

- As of 2005, Grande's nephew Orlando Erazo was the parish priest in El Paisnal.[10]

Notes

- ↑ http://fssca.net/pastreports/rutilio/rutilio2007.html, Father Rutilio Grande, Another Salvadoran "Revolutionary"

- ↑ RUTILIO GRANDE, SJ

- ↑ Remembering a Salvadoran Martyr

- ↑ "Archbishop Oscar Romero: A Saint for the Rest of Us", by Bea Scott, Just Good Company: A cyber journal of religion and culture, April 2003

- ↑ Penny Lernoux, The Cry of the People, New York: Penguin Books, 1982.

- ↑ Incident Listing in MIPT Terrorism Knowledge Base

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Report on the Situation of Human Rights in El Salvador, Chapter II: Right to Life, Organization of American States' Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (translated from Spanish), November 17, 1978

- ↑ A Century of Jesuit Martyrs, Company Online!: A Magazine of the U.S. Jesuits

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Óscar Romero", by Haydee Rodriguez, CatholicIreland.net, originally for the Irish Jesuit publication AMDG (undated)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Paul Jeffrey. After 25 years 'St. Romero of the World' still inspires, National Catholic Reporter, April 15, 2005

- ↑ Jon Sobrino, SJ, trans. Robert R. Barr, Archbishop Romero: Memories and Reflections, Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1990

- ↑ Greater Milwaukee Synod Sister Community: Rutilio Grande (accessed August 25, 2006)

- ↑ Greater Milwaukee Synod El Salvador Committee Newsletter, 2006

- ↑ Sister Cities: Rutilio Grande

External links

- Remembrances and Discussion of Rutilio Grande, CRISPAZ (Christians for Peace in El Salvador), SalvaNet, May/June 1997 (pp. 8–11)

- Carta a las Iglesias (Letter to the Churches), Universidad Centroamericana "José Simeón Cañas", Year 17, No. 371, February 1–15, 1997 (in Spanish - full edition devoted to Rutilio Grande and his legacy, includes text of the February, 1977 sermon)

References

- Martin Maier, Oscar Romero: Meister der Spiritualität. Herder (2001)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|