Run average

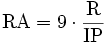

In baseball statistics, run average (RA) refers to measures of the rate at which runs are allowed or scored. For pitchers, the run average is the number of runs—earned or unearned—allowed per nine innings. It is calculated using this formula:

where

- R = Runs

- IP = Innings pitched

Run average for pitchers differs from the more commonly used earned run average (ERA) by adding unearned runs to the numerator. This measure is also known as total run average (TRA) or runs allowed average. For batters, the run average is the number of runs scored per at bat.[1]

Run average for pitchers

Although presentations of pitching statistics generally feature the ERA rather than the RA, the latter statistic is notable for both historical and analytical reasons. For early leagues or leagues for which statistics must be calculated from box scores, such as the Negro leagues, data on earned runs may be unavailable and RA may be the only statistic available.[2] The analytical case for RA appeared as early as 1976, when sportswriter Leonard Koppett proposed that RA would be a better measure of pitcher performance than ERA.[3] Subsequently, sabermetrician Bill James wrote, "I think that the distinction between earned runs and unearned runs is silly and artificial, a distinction having no meaning except in the eyes of some guy up in the press box."[4]

In baseball, defense—that is, preventing the opponent from scoring runs—is the joint responsibility of the pitcher and the fielders. ERA attempts to adjust for some of the influence of the fielders on a pitcher's runs allowed by removing runs that are scored because of fielding errors—that is, unearned runs. However, removing unearned runs doesn't adequately adjust for the effects of defensive support, because it makes no adjustment for other important aspects of fielding, such as proficiency at turning double plays, throwing out base stealers, and fielding range. Errors are the only aspect of fielding that ERA adjusts for, and are generally regarded as a small part of fielding in modern baseball.[5]

Another problem with ERA is the inconsistency with which official scorers call plays as errors. The rules give scorers considerable discretion regarding the plays that can be called as errors. Researcher Craig R. Wright found large differences between teams in the rate at which their scorers called errors, and even found some evidence of home team bias—that is, calling errors to favor the statistics of players for the home team.[6]

While ERA doesn't charge the pitcher for the runs that result from errors, it may tend to over correct for the influence of fielding. Even though unearned runs would not have scored without an error, in most cases the pitcher also contributes to the scoring of the unearned run—either by allowing the opposing player to reach base via a walk or hit, or by allowing a subsequent batter a hit that advances and scores the runner. During the early days of baseball history, this over correction for fielding errors caused pitchers on bad teams to be overrated in terms of ERA.[7]

Removing unearned runs in calculating ERA may be useful if they are unrelated to pitcher performance, but Wright concludes that fielding errors are somewhat dependent on a pitcher's style. Because errors occur most often on ground balls, pitchers with high strikeout rates who give up fly balls are likely to give up fewer unearned runs than groundball control-type pitchers. For example, Ron Guidry—a flyball power pitcher—and Tommy John—a groundball control pitcher—were teammates on the Yankees from 1979 to 1982, supported by the same defense. During that period, 13.7% of John's runs allowed were unearned, compared to 9.8% of Guidry's. Wright concludes that this difference is attributable to their pitching styles, and thus, that unearned runs are partially attributable to the pitcher.[8]

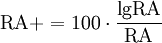

Adjusted RA+

Similar to adjusted ERA+, it is possible to adjust RA for the ballpark effects and compare it to the league average. The formula for this adjustment is:

where

- lgRA = park-adjusted league run average

- RA = the pitcher's run average.

Values of RA+ above 100 indicate better-than-average pitching performance. Unlike unadjusted RA, which must be higher than unadjusted ERA, a pitcher's adjusted RA+ can be either higher or lower than his adjusted ERA+.

See also

Notes

References

- Holway, John B. (2001). The Complete Book of Baseball's Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History. Fern Park, FL: Hastings House Publishers. ISBN 0-8038-2007-0.

- James, Bill (1986). The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: Villard Books. ISBN 0-394-53713-0.

- James, Bill (1987). The Bill James Baseball Abstract 1987. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-34180-5.

- Thorn, John; Pete Palmer (1982). The Hidden Game of Baseball. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-18283-X.

- Wright, Craig R.; Tom House (1989). The Diamond Appraised. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-67769-1.