Rule 30

Rule 30 is a one-dimensional binary cellular automaton rule introduced by Stephen Wolfram in 1983.[2] Using Wolfram's classification scheme, Rule 30 is a Class III rule, displaying aperiodic, chaotic behaviour.

This rule is of particular interest because it produces complex, seemingly random patterns from simple, well-defined rules. Because of this, Wolfram believes that Rule 30, and cellular automata in general, are the key to understanding how simple rules produce complex structures and behaviour in nature. For instance, a pattern resembling Rule 30 appears on the shell of the widespread cone snail species Conus textile. Rule 30 has also been used as a random number generator in Mathematica,[3] and has also been proposed as a possible stream cipher for use in cryptography.[4]

Rule 30 is so named because 30 is the smallest Wolfram code which describes its rule set (as described below). The mirror image, complement, and mirror complement of Rule 30 have Wolfram codes 86, 135, and 149, respectively.

Rule set

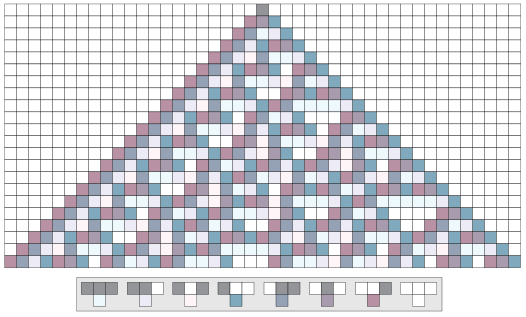

In all of Wolfram's elementary cellular automata, an infinite one-dimensional array of cellular automaton cells with only two states is considered, with each cell in some initial state. At discrete time intervals, every cell spontaneously changes state based on its current state and the state of its two neighbors. For Rule 30, the rule set which governs the next state of the automaton is:

| current pattern | 111 | 110 | 101 | 100 | 011 | 010 | 001 | 000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| new state for center cell | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

The following diagram shows the pattern created, with cells colored based on the previous state of their neighborhood. Darker colors represent "1" and lighter colors represent "0". Time increases down the vertical axis.

Structure and properties

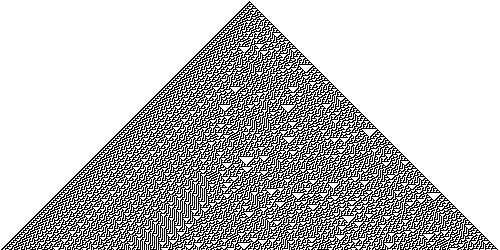

The following pattern emerges from an initial state in a single cell with state 1 (shown as black) is surrounded by cells with state 0 (white).

Rule 30 cellular automaton

Here, the vertical axis represents time and any horizontal cross-section of the image represents the state of all the cells in the array at a specific point in the pattern's evolution. Several motifs are present in this structure, such as the frequent appearance of white triangles and a well-defined striped pattern on the left side; however the structure as a whole has no discernible pattern. The number of black cells at generation  is given by the sequence

is given by the sequence

and is approximately  .

.

As is apparent from the image above, Rule 30 generates seeming randomness despite the lack of anything that could reasonably be considered random input. Stephen Wolfram proposed using its center column as a pseudorandom number generator (PRNG); it passes many standard tests for randomness, and Wolfram uses this rule in the Mathematica product for creating random integers. Although Rule 30 produces randomness on many input patterns, there are also an infinite number of input patterns that result in repeating patterns. The trivial example of such a pattern is the input pattern only consisting of zeros. A less trivial example, found by Matthew Cook, is any input pattern consisting of infinite repetitions of the pattern '00001000111000', with repetitions optionally being separated by six ones. Many more such patterns were found by Frans Faase. See Repeating Rule 30 patterns.

Sipper and Tomassini have shown that as a random number generator Rule 30 exhibits poor behavior on a chi squared test when applied to all the rule columns as compared to other cellular automaton-based generators.[5] The authors also expressed their concern that "The relatively low results obtained by the rule 30 CA may be due to the fact that we considered N random sequences generated in parallel, rather than the single one considered by Wolfram." (page 6 [6])

Chaos

Wolfram based his classification of Rule 30 as chaotic based primarily on its visual appearance, but it was later shown to meet more rigorous definitions of chaos proposed by Devaney and Knudson. In particular, according to Devaney's criteria, Rule 30 displays sensitive dependence on initial conditions (two initial configurations that differ only in a small number of cells rapidly diverge), its periodic configurations are dense in the space of all configurations, according to the Cantor topology on the space of configurations (there is a periodic configuration with any finite pattern of cells), and it is mixing (for any two finite patterns of cells, there is a configuration containing one pattern that eventually leads to a configuration containing the other pattern). According to Knudson's criteria, it displays sensitive dependence and there is a dense orbit (an initial configuration that eventually displays any finite pattern of cells). Both of these characterizations of the rule's chaotic behavior follow from a simpler and easy to verify property of Rule 30: it is left permutative, meaning that if two configurations C and D differ in the state of a single cell at position i, then after a single step the new configurations will differ at cell i + 1.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ Stephen Coombes (February 2009). "The Geometry and Pigmentation of Seashells". www.maths.nottingham.ac.uk. University of Nottingham. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- ↑ Wolfram, S. (1983). "Statistical mechanics of cellular automata". Rev. Mod. Phys. 55 (3): 601–644. Bibcode:1983RvMP...55..601W. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.55.601.

- ↑ "Random Number Generation". Wolfram Mathematica 8 Documentation. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ Wolfram, S. (1985). "Cryptography with cellular automata". Proceedings of Advances in Cryptology - CRYPTO '85. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 218, Springer-Verlag. p. 429. See also Meier, Willi; Staffelbach, Othmar (1991). "Analysis of pseudo random sequences generated by cellular automata". Advances in Cryptology: Proc. Workshop on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques, EUROCRYPT '91. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 547, Springer-Verlag. p. 186.

- ↑ Sipper, Moshe; Tomassini, Marco (1996). "Generating parallel random number generators by cellular programming". International Journal of Modern Physics C 7 (2): 181–190. Bibcode:1996IJMPC...7..181S. doi:10.1142/S012918319600017X.

- ↑ Sipper, Moshe; Tomassini, Marco (1996). "Generating parallel random number generators by cellular programming". International Journal of Modern Physics C 7 (2): 181–190. Bibcode:1996IJMPC...7..181S. doi:10.1142/S012918319600017X.

- ↑ Cattaneo, Gianpiero; Finelli, Michele; Margara, Luciano (2000). "Investigating topological chaos by elementary cellular automata dynamics". Theoretical Computer Science 244 (1–2): 219–241. doi:10.1016/S0304-3975(98)00345-4. MR 1774395.

- Wolfram, Stephen, 1985, Cryptography with Cellular Automata, CRYPTO'85.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rule 30. |

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Rule 30", MathWorld.

- Rule 30 in Wolfram's atlas of cellular automata

- Rule 30: Wolfram's Pseudo-random Bit Generator. Recipe 32 at David Griffeath's Primordial Soup Kitchen.

- Repeating Rule 30 patterns. A list of patterns that, when repeated to fill the cells of a Rule 30 automaton, repeat themselves after finitely many time steps. Frans Faase, 2003. Archived from the Original on 2013-08-08

- Paving Mosaic Fractal. Basic introduction to the pattern of Rule 30 from the perspective of a LOGO software expert Olivier Schmidt-Chevalier.

- TED Talk from February 2010. Stephen Wolfram speaks about computing a theory of everything where he talks about rule 30 among other things.