Rule 110

The Rule 110 cellular automaton (often simply Rule 110) is an elementary cellular automaton with interesting behavior on the boundary between stability and chaos. In this respect it is similar to Game of Life. Rule 110 is known to be Turing complete. This implies that, in principle, any calculation or computer program can be simulated using this automaton.

Definition

In an elementary cellular automaton, a one-dimensional pattern of 0's and 1's evolves according to a simple set of rules. Whether a point in the pattern will be 0 or 1 in the new generation depends on its current value, as well of that of its two neighbors. The Rule 110 automaton has the following set of rules:

| current pattern | 111 | 110 | 101 | 100 | 011 | 010 | 001 | 000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| new state for center cell | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

The name "Rule 110" derives from the fact that this rule can be summarized in the binary sequence 01101110; interpreted as a binary number, this corresponds to the decimal value 110.

History

Around 2000, Matthew Cook published a proof that Rule 110 is Turing complete, i.e., capable of universal computation, which Stephen Wolfram had conjectured in 1985. Cook presented his proof at the Santa Fe Institute conference CA98 before the publishing of Wolfram's book. This resulted in a legal affair based on a non-disclosure agreement with Wolfram Research. Wolfram Research blocked publication of Cook's proof for 2 years.[1]

Interesting properties

Among the 88 possible unique elementary cellular automata, Rule 110 is the only one for which Turing completeness has been proven, although proofs for several similar rules should follow as simple corollaries, for instance Rule 124, where the only directional (asymmetrical) transformation is reversed. Rule 110 is arguably the simplest known Turing complete system.[1][2]

Rule 110, like the Game of Life, exhibits what Wolfram calls "Class 4 behavior", which is neither completely stable nor completely chaotic. Localized structures appear and interact in various complicated-looking ways.[3]

Matthew Cook proved Rule 110 capable of supporting universal computation. Rule 110 is a simple enough system to suggest that naturally occurring physical systems may also be capable of universality— meaning that many of their properties will be undecidable, and not amenable to closed-form mathematical solutions.[4]

Turing machine simulation overhead

The original emulation of a Turing machine contained an exponential time overhead due to the encoding of the Turing machine's tape using a unary numeral system. Neary and Woods (2006) modified the construction to use only a polynomial overhead.[5]

The proof of universality

Matthew Cook presented his proof of the universality of Rule 110 at a Santa Fe Institute conference, held before the publication of NKS. Wolfram Research claimed that this presentation violated Cook's nondisclosure agreement with his employer, and obtained a court order excluding Cook's paper from the published conference proceedings. The existence of Cook's proof nevertheless became known. Interest in his proof stemmed not so much from its result as from its methods, specifically from the technical details of its construction [citation needed]. The character of Cook's proof differs considerably from the discussion of Rule 110 in NKS. Cook has since written a paper setting out his complete proof.[1]

Cook proved that Rule 110 was universal (or Turing complete) by showing it was possible to use the rule to emulate another computational model, the cyclic tag system, which is known to be universal. He first isolated a number of spaceships, self-perpetuating localized patterns, that could be constructed on an infinitely repeating pattern in a Rule 110 universe. He then devised a way for combinations of these structures to interact in a manner that could be exploited for computation.

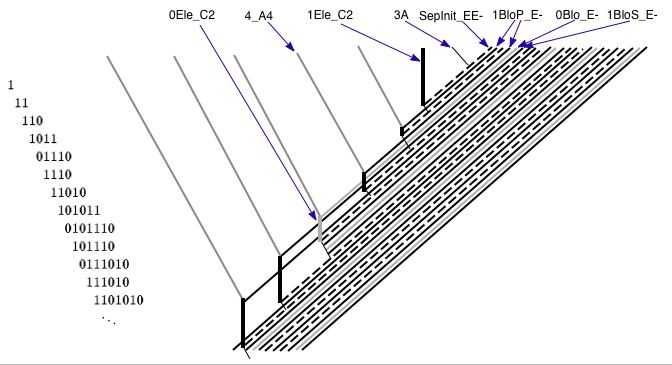

Spaceships in Rule 110

The function of the universal machine in Rule 110 requires an infinite number of localized patterns to be embedded within an infinitely repeating background pattern. The background pattern is fourteen cells wide and repeats itself exactly every seven iterations. The pattern is 00010011011111.

Three localized patterns are of particular importance in the Rule 110 universal machine. They are shown in the image below, surrounded by the repeating background pattern. The leftmost structure shifts to the right two cells and repeats every three generations. It comprises the sequence 0001110111 surrounded by the background pattern given above, as well as two different evolutions of this sequence.

In the figures, time elapses from top to bottom: the top line represents the initial state, and each following line the state at the next time.

The center structure shifts left eight cells and repeats every thirty generations. It comprises the sequence 1001111 surrounded by the background pattern given above, as well as twenty-nine different evolutions of this sequence.

The rightmost structure remains stationary and repeats every six generations. It comprises the sequence 111 surrounded by the background pattern given above, as well as five different evolutions of this sequence.

Below is an image showing the first two structures passing through each other without interacting other than by translation (left), and interacting to form the third structure (right).

There are numerous other spaceships in Rule 110, but they do not feature as prominently in the universality proof.

Constructing the cyclic tag system

The cyclic tag system machinery has three main components:

- A data string which is stationary;

- An infinitely repeating series of finite production rules which start on the right and move leftward;

- An infinitely repeating series of clock pulses which start on the left and move rightward.

The initial spacing between these components is of utmost importance. In order for the cellular automaton to implement the cyclic tag system, the automaton's initial conditions must be carefully selected so that the various localized structures contained therein interact in a highly ordered way.

The data string in the cyclic tag system is represented by a series of stationary repeating structures of the type shown above. Varying amounts of horizontal space between these structures serve to differentiate 1 symbols from 0 symbols. These symbols represent the word on which the cyclic tag system is operating, and the first such symbol is destroyed upon consideration of every production rule. When this leading symbol is a 1, new symbols are added to the end of the string; when it is 0, no new symbols are added. The mechanism for achieving this is described below.

Entering from the right are a series of left-moving structures of the type shown above, separated by varying amounts of horizontal space. Large numbers of these structures are combined with different spacings to represent 0s and 1s in the cyclic tag system's production rules. Because the tag system's production rules are known at the time of creation of the program, and infinitely repeating, the patterns of 0s and 1s at the initial condition can be represented by an infinitely repeating string. Each production rule is separated from the next by another structure known as a rule separator (or block separator), which moves towards the left at the same rate as the encoding of the production rules.

When a left-moving rule separator encounters a stationary symbol in the cyclic tag system's data string, it causes the first symbol it encounters to be destroyed. However, its subsequent behavior varies depending on whether the symbol encoded by the string had been a 0 or a 1. If a 0, the rule separator changes into a new structure which blocks the incoming production rule. This new structure is destroyed when it encounters the next rule separator.

If, on the other hand, the symbol in the string was a 1, the rule separator changes into a new structure which admits the incoming production rule. Although the new structure is again destroyed when it encounters the next rule separator, it first allows a series of structures to pass through towards the left. These structures are then made to append themselves to the end of the cyclic tag system's data string. This final transformation is accomplished by means of a series of infinitely repeating, right-moving clock pulses, in the right-moving pattern shown above. The clock pulses transform incoming left-moving 1 symbols from a production rule into stationary 1 symbols of the data string, and incoming 0 symbols from a production rule into stationary 0 symbols of the data string.

Cyclic tag system working

The reconstruction of a CTS in Rule 110 was using a regular language to Rule 110 over an evolution space of 56,240 cells to 57,400 generations. Writing the sequence 1110111 on the tape of cyclic tag system and a leader component at the end with two solutions.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Complex Systems 15, Issue 1, 2004.

- ↑ Stephen Wolfram, A New Kind of Science p.169.

- ↑ Stephen Wolfram, A New Kind of Science p.229.

- ↑ Rule 110 – Wolfram Alpha

- ↑ Neary, T. and Woods, D., P-completeness of cellular automaton Rule 110, Automata, Languages and Programming, 2006

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rule 110. |

- Cook, Matthew (2004) "Universality in Elementary Cellular Automata", Complex Systems 15: 1-40.

- Cook, Matthew (2008) "A Concrete View of Rule 110 Computation", In The Complexity of Simple Programs, T. Neary, D.Woods, A. K. Seda, and N. Murphy (Eds.), 31-55.

- Martínez, Genaro J.; Adamatzky, A.; Chen, Fangyue; Chua, Leon (2012) "On Soliton Collisions between Localizations in Complex Elementary Cellular Automata: Rules 54 and 110 and Beyond", Complex Systems 21 (2): 117-142.

- Martínez, Genaro J.; Adamatzky, A.; Stephens, Christopher R.; Hoeflich, Alejandro F. (2011) "Cellular automaton supercolliders", Int. J. of Modern Physics C 22 (4): 419-439.

- Martínez, Genaro J.; McIntosh, Harold V.; Mora, Juan C. S. T.; Vergara, Sergio V. C. (2003-2008) "Reproducing the cyclic tag systems developed by Matthew Cook with Rule 110 using the phases fi_1", Journal of Cellular Automata 6 (2-3): 121-161.

- Martínez, Genaro J.; McIntosh, Harold V.; Mora, Juan C. S. T.; Vergara, Sergio V. C. (2008) "Determining a regular language by glider-based structures called phases fi_1 in Rule 110", Journal of Cellular Automata 3 (3): 231-270.

- Martínez, Genaro J.; McIntosh, Harold V.; Mora, Juan C. S. T.; Vergara, Sergio V. C. (2007) "Rule 110 objects and other constructions based-collisions", Journal of Cellular Automata 2 (3): 219-242.

- Martínez, Genaro J.; McIntosh, Harold V.; Mora, Juan C. S. T. (2006) "Gliders in Rule 110", Int. J. of Unconventional Computing 2: 1-49.

- Martínez, Genaro J.; McIntosh, Harold V.; Mora, Juan C. S. T. (2003) "Production of gliders by collisions in Rule 110", Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2801: 175-182.

- Martínez, Genaro J.; McIntosh, Harold V. (2001) "ATLAS: Collisions of gliders as phases of ether in rule 110".

- McIntosh, Harold V. (1999) "Rule 110 as it relates to the presence of gliders".

- McIntosh, Harold V. (2002) "Rule 110 Is Universal!".

- Neary, Turlough; and Woods, Damien (2006) "P-completeness of cellular automaton Rule 110", Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4051: 132-143.

- Stephen Wolfram (2002) A New Kind of Science. Wolfram Media, Inc. ISBN 1-57955-008-8

External links

- Rule 110 in Wolfram's atlas of cellular automata

- For a nontechnical discussion of Rule 110 and its universality, see: A New Kind of Science p.690

- Wolfram Science – Rule 110

- Rule 110 repository