Rough music

Rough music, also known as ran-tan or ran-tanning, is an English folk custom, a practice in which a raucous punishment is dramatically enacted to humiliate one or more people who have violated, in a domestic or public context, standards commonly upheld within the community.[1] Frequent during the 18th and 19th centuries and probably earlier, it survived into the 20th century in a few places, such as Rampton, Nottinghamshire (1909),[2] Middleton Cheney (1909) and Blisworth (1920s and 1936), Northamptonshire.[3]

The Skimmington ride or Skimmity ride, as described by Thomas Hardy in The Mayor of Casterbridge, also known as riding the stang, is a version of this custom. Other local names include "tin-canning", "tin-kettling", "banging-out", "lew-belling" or "lowbelling" (all recorded from parts of Northamptonshire).[3]

Description

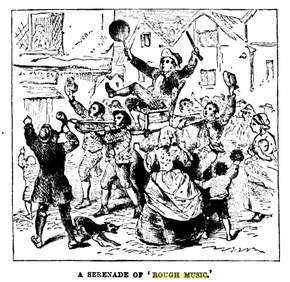

Noisy, masked processions were held outside the home of the supposed wrongdoer, involving the cacophonous rattling of bones and cleavers, the ringing of bells, hooting, blowing bull's horns, the banging of frying pans, saucepans, kettles, or other kitchen or barn implements with the intention of creating long-lasting embarrassment to the alleged perpetrator.[4] During a rough music performance, the victim could be displayed upon a pole or donkey (in person or as an effigy), their "crimes" becoming the subject of mime, theatrical performances or recitatives, along with a litany of obscenities and insults.[4]

Alternatively, one of the participants would "ride the stang" (a pole carried between the shoulders of two or more men or youths) while banging an old kettle or pan with a stick and reciting a rhyme (called a "nominy") such as the following:

- With a ran, tan, tan,

- On my old tin can,

- Mrs. _______ and her good man.

- She bang'd him, she bang'd him,

- For spending a penny when he stood in need.

- She up with a three-footed stool;

- She struck him so hard, and she cut so deep,

- Till the blood run down like a new stuck sheep![5]

The participants were generally young men temporarily bestowed with the power of rule over the everyday affairs of the community.[4] Issues of sexuality and domestic hierarchy most often formed the pretexts for rough music,[4] including acts of domestic violence or child abuse. Where effigies of the "wrongdoers" were made they were frequently burned as the climax of the event (as the inscription on the Rampton photograph indicates[2]) or "ritually drowned" (thrown into a pond or river). Ran-tanning would often be repeated for three nights running, unless the humiliated victims had already fled.[3]

A rough music song originating from South Stoke, Oxfordshire:[6]

- There is a man in our town

- Who often beats his wife,

- So if he does it any more,

- We'll put his nose right out before.

- Holler boys, holler boys,

- Make the bells ring,

- Holler boys, holler boys.

- God save the King.

As forms of vigilantism that were likely to lead to public disorder, ran-tanning and similar activities were banned under the Highways Act of 1882.[2]

Equivalents include the German haberfeldtreiben and katzenmusik, Italian scampanate and French charivari.[4] Instances of rough music in the United States were known as shivarees.

Similar customs

Many folk customs around the world have involved making loud noises to scare away evil spirits.[7]

Tuneless, cacophonous "rough music", played on horns, bugles, whistles, tin trays and frying pans, was a feature of the custom known as Teddy Rowe's Band. This had taken place annually, possibly for several centuries, in the early hours of the morning, to herald the arrival of Pack Monday Fair at Sherborne, Dorset, until it was banned by the police in 1964 because of hooliganism the previous year.[8] The fair is still held, on the first Monday after Old Michaelmas Day (10 October)[9] – St Michael's Day in the Old Style calendar.

The Tin Can Band at Broughton, Northamptonshire, a seasonal custom, takes place at midnight on the third Sunday in December. The participants march around the village for about an hour, rattling pans, dustbin lids, kettles and anything else that will make a noise.[10][11] The council once attempted to stop the tin-canning; participants were summoned and fined, but a dance was organised to raise money to pay the fines and the custom continues.[3][11] The village is sufficiently proud of its custom for it to feature on the village sign.[12]

See also

- Skimmington

- Chivaree

References

- ↑ Thompson, E. P. (1992). "Rough Music Reconsidered" (PDF). Folklore 103: 3–26. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1992.9715826. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 The Nottinghamshire Heritage Gateway: Folklore and customs, by Dr Peter Millington Includes a rare photograph of a ran-tan at Rampton, Nottinghamshire (1909)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Dorothy A Grimes, Like Dew Before the Sun – Life and Language in Northamptonshire, pp. 6–8, Privately published, Stanley L Hunt (printers), Rushden, 1991. ISBN 0-9518496-0-3

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Cox, Christoph (2004). Audio Culture. London: Continuum. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-8264-1614-4.

- ↑ Archive.org: John Brand, The Popular Antiquities of Great Britain, (1905 edition) p. 563 (quoting Costume of Yorkshire, 1814)

- ↑ Bloxham, Christine (2005). Folklore of Oxfordshire. Tempus. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-7524-3664-3.

- ↑ Bartleby.com The Golden Bough (1922 edition), Sir James George Frazer, Ch 56 The Public Expulsion of Evils §1 The Omnipresence of Demons

- ↑ Hole, Christina (1978). A Dictionary of British Folk Customs, pp291–292, Paladin Granada, ISBN 0-586-08293-X

- ↑ Visit Dorset: Sherborne Pack Monday Fair

- ↑ John Kirpatrick, Sleeve notes for Wassail! A Traditional Celebration of an English Midwinter, John Kirpatrick et al., Fellside Records, FECD125 (1997)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Information Britain: Broughton Tin Can Band, Northamptonshire

- ↑ Broughton Parish Plan (pdf)

External links

- Notbored.org: Rough music

- Thomas Hardy, The Mayor of Casterbridge (1884), chapters 36, 39. ISBN 0-00-424535-0

- Terry Pratchett, I Shall Wear Midnight (2010), chapter 2. ISBN 978-0-385-61107-7

- Patrick Gale, Rough Music (2000) ISBN 978-0-00-655220-8

- Archive.org: John Brand, The Popular Antiquities of Great Britain, (1905 edition) pp. 551–552. Several early examples of rough music, skimmington rides and similar unnamed customs between 1562 and 1790, including one in Seville (1593)

- Archive.org: John Brand, The Popular Antiquities of Great Britain, (1905 edition) p. 563. Descriptions of Riding the Stang, including a ran-tan rhyme