Romanian subdialects

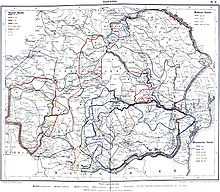

The Romanian subdialects (subdialecte or graiuri) are the several varieties of the Romanian language, more specifically of its Daco-Romanian dialect. All linguists seem to agree on classifying the subdialects into two types, northern and southern, but further taxonomy is less clear, so that the number of subdialects varies between two and five, occasionally twenty. Most recent works seem to favor a number of three clear subdialects, corresponding to the regions of Wallachia, Moldavia, and Banat (all of which actually extend into Transylvania), and an additional group of varieties covering the remainder of Transylvania, two of which are more clearly distinguished, in Crișana and Maramureș, that is, a total of five.

The main criteria used in their classification are the phonetic features. Of less importance are the morphological, syntactical, and lexical particularities, as these are too small to provide clear distinctions.

All Romanian subdialects are mutually intelligible.

Terminology

The term dialect is often avoided when speaking about the Daco-Romanian varieties, especially by Romanian linguists, for two main reasons. First, according to many linguists, the Romanian language (in the wider sense) is already divided into four dialects: Daco-Romanian, Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, and Istro-Romanian; these, according to other linguists, are separate languages. The second reason is that, in Romanian, the term dialect is used in its narrow sense of large group of speech varieties that show considerable differences compared to the reference language (standard Romanian in this case), while other terms are used for smaller, more similar divisions. Unlike other Romance languages, all Daco-Romanian varieties are very similar to each other,[1][2] so that usually they are called subdialects.

Criteria

Early dialectal studies of Romanian tended to divide the language according to administrative regions, which in turn were usually based on historical provinces. This led sometimes to divisions into three varieties, Wallachian, Moldavian, and Transylvanian,[3] or four, adding one for Banat.[4] Such classifications came to be made obsolete by the later, more rigorous studies, based on a more thorough knowledge of linguistic facts.

The publication of a linguistic atlas of Romanian by Gustav Weigand in 1908 and later, in the interwar period, of a series of dialectal atlases by a team of Romanian linguists,[5] containing detailed and systematic data gathered across the areas inhabited by Romanians, allowed researchers to elaborate more reliable dialectal descriptions of the language.

The criteria given the most weight in establishing the dialectal classification were the regular phonetic features, in particular phenomena such as palatalization, monophthongization, vowel changes, etc. Only secondarily were morphological particularities used, especially where the phonetic features proved to be insufficient. Lexical particularities were the least relied upon.[6]

Phonetic criteria

Only the most systematic phonetic features have been considered in dialectal classifications, such as the following.

- fricatization and palatalization of the affricates [t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ];

- closing of the unstressed non-initial [e] to [i];

- closing of word-final [ə] to [ɨ];

- opening of pre-stress [ə] to [a];

- monophthongization of [e̯a] to [e] or [ɛ] when the next syllable contains [e];

- pronunciation of [e] and [i] after fricatives [s z ʃ ʒ] and affricate [t͡s];

- pronunciation of [e] after labials;

- pronunciation of the words cîine, mîine, pîine with [ɨj] or [ɨ].

- presence of a final whispered [u];

- the degree of palatalization of labials;

- the degree of palatalization of dentals;

- palatalization of the fricatives [s z] and the affricate [t͡s];

- palatalization of fricatives [ʃ ʒ].

For ease of presentation, some of the phonetic features above are described by taking the standard Romanian pronunciation as reference, even though in dialectal characterizations such a reference is not necessary and etymologically speaking the process might have had the opposite direction. A criterion such as "closing of word-final [ə] to [ɨ]" should be understood to mean that some Romanian subdialects have [ɨ] in word-final positions where others have [ə] (compare, for instance, Moldavian [ˈmamɨ] vs Wallachian [ˈmamə], both meaning "mother").

The most important phonetic process that helps in distinguishing the Romanian subdialects concerns the consonants pronounced in standard Romanian as the affricates [t͡ʃ] and [d͡ʒ]:

- In the Wallachian subdialect they remain affricates.

- In the Moldavian subdialect they become the fricatives [ʃ, ʒ].

- In the Banat subdialect they become the palatal fricatives [ʃʲ, ʒʲ].

- In the Transylvanian varieties they diverge: [t͡ʃ] remains an affricate, whereas [d͡ʒ] becomes [ʒ].

Classification

The Romanian subdialects have proven hard to classify and are highly debated. Various authors, considering various classification criteria, arrived at different classifications and divided the language into two to five subdialects, but occasionally as many as twenty:[7][8]

- 2 subdialects: Wallachian, Moldavian;[9]

- 3 subdialects: Wallachian, Moldavian, Banat;[10]

- 4 subdialects: Wallachian, Moldavian, Banat, Crișana;[11]

- 4 subdialects: Wallachian, Moldavian, Banat–Hunedoara, northern Transylvania;[12]

- 5 subdialects: Wallachian, Moldavian, Banat, Crișana, Maramureș.[13]

- 20 subdialects.[14]

Most modern classifications divide the Romanian subdialects into two types, southern and northern, further divided as follows:

- The southern type has only one member:

- the Wallachian subdialect (subdialectul muntean or graiul muntean), spoken in the southern part of Romania, in the historical regions of Muntenia, Oltenia, Dobruja (the southern part), but also extending in the southern parts of Transylvania. The orthoepy as well as the other aspects of the standard Romanian are largely based on this subdialect.[15][16][17]

- The northern type consists of several subdialects:

- the Moldavian subdialect (subdialectul moldovean or graiul moldovean), spoken in the historical region of Moldavia, now split among Romania, the Republic of Moldova, and Ukraine (Bukovina and Bessarabia[18]), as well as northern Dobruja;

- the Banat subdialect (subdialectul bănățean or graiul bănățean), spoken in the historical region of Banat, including parts of Serbia;

- a group of Transylvanian varieties (graiuri transilvănene), among which two or three varieties are often distinguished, those of Crișana (graiul crișean), Maramureș (graiul maramureșean), and sometimes Oaș (graiul oșean).[19] This distinction, however, is more difficult to make than for the other subdialects, since the Transylvanian varieties are much more finely divided and show features that prove them to be transition varieties of the neighboring subdialects.

Bibliography

- Vasile Ursan, "Despre configurația dialectală a dacoromânei actuale", Transilvania (new series), 2008, No. 1, pp. 77–85 (Romanian)

- Ilona Bădescu, "Dialectologie", teaching material for the University of Craiova.

Notes

- ↑ Vasile Ursan, in "Despre configurația dialectală a dacoromânei actuale", p. 77, says: "The Daco-Romanian varieties are characterized by an exceptional linguistic unity."

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, entry on "Romanian"

- ↑ Mozes Gaster, 1891

- ↑ Heimann Tiktin, 1888

- ↑ Atlasul lingvistic român, in several volumes, coordinated by Sextil Pușcariu and based on field work by Sever Pop and Emil Petrovici.

- ↑ Such criteria were proposed and used by Emil Petrovici, Romulus Todoran, Emanuel Vasiliu, and Ion Gheție, among others.

- ↑ Marius Sala, From Latin to Romanian: The historical development of Romanian in a comparative Romance context, Romance Monographs, 2005. p. 163

- ↑ Marius Sala, Enciclopedia limbilor romanice, 1989, p. 90

- ↑ According to Alexandru Philippide, Iorgu Iordan, Emanuel Vasiliu.

- ↑ According to Gustav Weigand, Sextil Pușcariu (in his earlier works).

- ↑ According to Emil Petrovici, in certain analyses. He called the Crișana variety "the north-western subdialect".

- ↑ According to Ion Gheție and Al. Mareș.

- ↑ According to Sextil Pușcariu (in latter works), Romulus Todoran, Emil Petrovici, Ion Coteanu, and current handbooks.

- ↑ According to Gheorghe Ivănescu, Istoria limbii române, Editura Junimea, Iași, 1980, cited by Vasile Ursan.

- ↑ Mioara Avram, Marius Sala, May we introduce the Romanian language to you?, The Romanian Cultural Foundation Publishing House, 2000, ISBN 973-577-224-8, ISBN 978-973-577-224-6, p. 111

- ↑ Mioara Avram, Marius Sala, Enciclopedia limbii române, Editura Univers Enciclopedic, 2001 (Romanian) At page 402 the authors write: "The Romanian literary or exemplary pronunciation is materialized in the pronunciation of the middle-aged generation of intellectuals in Bucharest. While the orthoepy has been formed on the basis of the Wallachian subdialect, it departs from it in certain aspects, by adopting phonetic particularities from other subdialects."

- ↑ Ioana Vintilă-Rădulescu, "Unele inovaţii ale limbii române contemporane şi ediţia a II-a a DOOM-ului" (Romanian) Page 2: "The literary or exemplary language use, in general, is materialized in the speech and writing of the middle generation of intellectuals, first of all from Bucharest."

- ↑ Marius Sala, From Latin to Romanian: The historical development of Romanian in a comparative Romance context, Romance Monographs, 2005. p. 164

- ↑ Institutul de Cercetări Etnologice și Dialectologice, Tratat de dialectologie româneascǎ, Editura Scrisul Românesc, 1984, p. 357 (Romanian)

| ||||||||||||||||||||