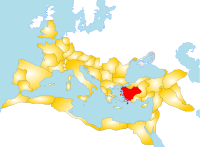

Asia (Roman province)

| Provincia Asia ἐπαρχία Ἀσίας | |||||

| Province of the Roman Empire | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Ephesus | ||||

| Historical era | Classical Antiquity | ||||

| - | Conquest of the Kingdom of Pergamon | 133 BC | |||

| - | Division by emperor Diocletian | c. 293 | |||

| - | Anatolic Theme established | 7th Century | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

The Roman province of Asia or Asiana (Greek: Ἀσία or Ἀσιανή), in Byzantine times called Phrygia, was an administrative unit added to the late Republic. It was a Senatorial province governed by a proconsul. The arrangement was unchanged in the reorganization of the Roman Empire in 211.

Geography

Asia province originally consisted of Mysia, the Troad, Aeolis, Lydia, Ionia, Caria, and the land corridor through Pisidia to Pamphylia. Aegean islands except Crete, were part of the Insulae (province) of Asiana. Part of Phrygia was given to Mithridates V Euergetes before it was reclaimed as part of the province in 116 BC. Lycaonia was added before 100 BC while the area around Cibyra was added in 82 BC. The southeast region of Asia province was later reassigned to the province of Cilicia. During, the empire, Asia province was bounded by Bithynia to the north, Lycia to the south, and Galatia to the east.[1]

Background

Antiochus III the Great had to give up Asia when the Romans crushed his army at the historic battle of Magnesia, in 190 BC. After the Treaty of Apamea (188 BC), the entire territory was surrendered to Rome and placed under the control of a client king at Pergamum.

With no apparent heir, Attalus III of Pergamum having been a close ally of Rome, chose to bequeath his kingdom to Rome. Upon Attalus’s passing in 133 BC, Manius Aquillius formally established the region as Asia province.[2] The bequest of the Attalid kingdom to Rome presented serious implications for neighboring territories. It was during this period of time that Pontus rose in status under the rule of Mithridates VI. He would prove to be a formidable foe to Rome’s success in Asia province and beyond.[3]

Exploitation

Rome had always been very reluctant to involve itself in matters to the east. It typically relied on allies to arbitrate in the case of a conflict. Very rarely would Rome send delegations to the east, much less have a strong governmental presence. This apathy did not change much even after the gift from Attalus in 133 BC. In fact, parts of the Pergamene kingdom were voluntarily relinquished to different nations. For example, Great Phrygia was given to Mithridates V of Pontus.[4]

While the Senate was hesitant in involving itself in Asian affairs, others had no such reluctance. A law passed by Gaius Gracchus in 123 BC gave the right to collect taxes in Asia to members of the equestrian order. The privilege of collecting taxes was almost certainly exploited by individuals from the Republic.[5]

In case a community was unable to pay taxes, they borrowed from Roman lenders but at exorbitant rates. This more often than not resulted in default on said loans and consequently led Roman lenders to seize the borrower’s land, their last remaining asset of value. In this way and by outright purchase, Romans dispersed throughout Asia province.[6]

Mithridates and Sulla

By 88 BC, Mithridates VI of Pontus had conquered virtually all of Asia. Capitalizing on the hatred of corrupt Roman practices, Mithridates instigated a mass revolt against Rome, ordering the slaughter of all Romans and Italians in the province.[7] Contemporary estimates of casualties ranged from 80,000 up to 150,000.[2]

Three years later, Lucius Cornelius Sulla defeated Mithridates in the First Mithridatic War and in 85 BC reorganized the province into eleven assize districts, each central to a number of smaller, subordinate cities. These assize centers, which developed into the Roman dioceses, included Ephesus, Pergamum - the old Attalid capital, Smyrna, Adramyttium, Cyzicus, Synnada, Apamea, Miletus, and Halicarnassus. The first three cities - Ephesus, Pergamum, and Smyrna - competed to be the dominant city-state in Asia province.[2] Age-old inter-city rivalry continued to inhibit any sort of progress towards provincial unity.

Military presence

Other than to quell occasional revolts, there was minimal military presence in Asia province, until forces led by Sulla set forth in their campaign against Mithridates VI. In fact, Asia province was unique in that it was one of the few ungarrisoned provinces of the empire. While no full legions were ever stationed inside the province, that is not to say that there was no military presence whatsoever.[8]

Legionary detachments were present in the Phrygian cities of Apamea and Amorium. Auxiliary cohorts were stationed in Phrygian Eumeneia while smaller groups of soldiers regularly patrolled the mountainous regions. High military presence in rural regions around 3rd century AD caused great civil unrest in the province.[9]

Augustus

After Augustus came to power, he established a proconsulship for the province of Asia, embracing the regions of Mysia, Lydia, Caria, and Phrygia. The proconsul spent much of his year-long term traveling throughout the province hearing cases and conducting other judicial business at each of the assize centers.[2] Rome’s transition from the Republic to the early Empire saw an important change in the role of existing provincial cities, which evolved from autonomous city-states to Imperial administrative centers.[10]

The beginning of the principate of Augustus also signaled the rise of new cities in Mysia, Lydia and Phrygia. The province grew to be an elaborate system of self-governing cities, each responsible for its own economics, taxes, and law in its territory. The reign of Augustus further signaled the start of urbanization of Asia province, as public building became the defining characteristic of a city.[11]

Emperor worship

Emperor worship was prevalent in provincial communities during the Roman empire. Soon after Augustus came to power, temples erected in his honor sprang up across Asia province. The establishment of provincial centers of emperor worship further spawned local cults. These sites served as models followed by other provinces throughout the empire.[12]

Emperor worship served as a way for subjects of Asia province to come to terms with imperial rule within the framework of their communities. Religious practices were very much a public affair and involved citizens in all its aspects including prayer, sacrifice, and processions. Rituals held in honor of a particular emperor frequently outnumbered those of other gods. No other cult matched the imperial cult in terms of dispersion and commonality.[13]

Decline

The 3rd century AD marked a serious decline in Asia province stemming in part from epidemic disease, beginning with the Antonine plague, the indiscipline of local soldiers and also the diminishing instances of voluntary civic generosity. The Gothic invasions of the 250s and 260s, part of the Crisis of the Third Century, contributed to failing feelings of security. Furthermore, as political and strategic emphasis shifted away from Asia province, it lost much of its former prominence.

In the 4th century, Diocletian divided Asia province into seven smaller provinces. During the 5th century and, until the mid-sixth century the cities and provinces western Anatolia experienced an economic renaissance. But after the great plague of 543 many cities towards the interior of the province declined to the point where they were indistinguishable from common villages by the time of the Persian and Arab invasions of the 7th century. On the other hand, leading cities from the early empire including Ephesus, Sardis, and Aphrodisias retained much of their former glory and came to serve as the new provincial capitals.[2] Asia remained a center of Roman and Hellenistic culture in the east for centuries. The territory remained part of the Byzantine Empire until the end of the 13th century.

Episcopal sees

Ancient episcopal sees of the Roman province of Asia I that are listed in the Annuario Pontificio as titular sees include:[14]

- Adramyttium

- Aegae (Nimrud-Kalesi)

- Algiza (Baliapasakov)

- Anaea (Anya)

- Anineta

- Antandrus (near Derveni)

- Arcadiopolis in Asia (Thira)

- Assus (Behram, Behramköy)

- Attaea (Dikeliköy)

- Aureliopolis in Asia (Freneli)

- Bareta (in the valley of the Cayster River)

- Briula (Billara)

- Caloe

- Colophon

- Cyme (Lamurt, Namurtköy)

- Dioshieron (Birgi? - lliceköy)

- Elaea

- Ephesus

- Erythrae

- Euaza (in the valley of the Cayster River)

- Lebedus

- Magnesia ad Maeandrum

- Mastaura in Asia

- Metropolis in Asia (ruins at Tratsa)

- Myrina

- Nea Aule

Ancient episcopal sees of the Roman province of Asia II that are listed in the Annuario Pontificio as titular sees include:[14]

- Clazomenae

- Magnesia ad Sipylum

- Phocaea

See also

- List of Roman governors of Asia

- Early centers of Christianity#Anatolia

References

- ↑ "Asia, Roman province." The Oxford Classical Dictionary. 3rd ed. 1996: p. 189-90

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 The Oxford Classical Dictionary. pp. 189f

- ↑ Mitchell, Stephen. Anatolia. Volume 1. (New York: Oxford University Press), 1993. p. 29

- ↑ Anatolia. p. 29

- ↑ Anatolia p. 30

- ↑ Anatolia p. 30

- ↑ Appian, History of Rome: The Mithridatic Wars.

- ↑ Anatolia p. 121

- ↑ Anatolia p. 121

- ↑ Anatolia p. 198

- ↑ Anatolia p. 198

- ↑ Anatolia p. 100

- ↑ Anatolia p. 112

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), "Sedi titolari", pp. 819-1013

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roman Asia. |

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||