Robert Hanbury Brown

Robert Hanbury Brown, AC FRS[1] (31 August 1916 – 16 January 2002) was a British astronomer and physicist born in Aruvankadu, India. He made notable contributions to the development of radar and he later conducted pioneering work in the field of radio astronomy.[2] He was rumoured to have been the original radar scientist who inspired the term boffin during World War II.[citation needed]

Early Years

Robert was born in India in 1916, the son of an army officer. His grandfather, Sir Robert Hanbury Brown, K.C.M.G., a notable irrigation engineer, was also one of the early pioneers of radio. Following his parents' divorce, his legal guardian was a consulting radio engineer.[3]

Career

After attending Tonbridge School, Brown studied electrical engineering at the University of London, from where he received a Master's degree in telecommunication in 1935. From 1936 to 1942 he worked for the Air Ministry, where he helped to develop radar.[4] He then joined the Tizard Mission and spent 3 years in Washington, D.C. to work with the Combined Research Group at the Naval Research Laboratory. After the end of the war he returned to Britain and rejoined the scientific civil service. A consultancy that had been set up by Sir Robert Watson-Watt, the father of radar, offered more interesting prospects for the conversion of wartime developments into peacetime technologies. Hanbury Brown allowed himself to be recruited and worked as a consulting engineer until Watson-Watt decided to move the firm to Canada. After pondering a number of career possibilities, he returned to academia in the autumn of 1949, when he joined Bernard Lovell's radio astronomy group at the University of Manchester.

Contributions

Hanbury came back to England because he wanted a higher title in the university so he and Ciril Hazard with his 218-ft radio telescope show that some cosmic radio waves were emanating from the Andromeda spiral galaxy, that was 2 million light years away from our own galaxy. This was an impression science they had thought that they were the origins of such emissions. Years later he and Hazard were in an investigation and discover the quasi-stellar objects that nowadays are known as the most disnt and oldest obejcts in the universe. Later he start thinking about a radio interferometer that would allow to measure the angular size of the two strongest radio sources in the sky, the Cygnus A and the Cassiopeia but he knew he needed an interforemeter so it could reach thousands of kilometers so he thought of a sound basis and then by 1952 he actually invented it.

Hanbury tried to prove that his intensity interferometer was functional. He did that by measuring the Dog Star’s diameter called Sirius despite the bad conditions in the sky at the time, being Winter in Britain between 1955 and 1956. After that, he looked for more stars which could have something special in them located in the Southern Hemisphere where there were the sky was less cloudy. He departed without his personal chair in Manchester. Moving to the University of Sidney during the year of 1962. He joined the Extraordinary Physiscs Department, and was put with Harry Messei as his roommate. This department was the first one to be multi-professional in Australia. The next interferometer from Hanbury was built in a sheep paddock, just outside Narriabi in New South Wales. His telescopes were 23 ft in diameter and were composed of 250 mirrors, moving in a track of 600 ft in diameter. The animals provided diversion and disruption. Some of the characteristics of the area were that droughts and floods were very common. Despite the non-coopertating features of the place, the interferometer

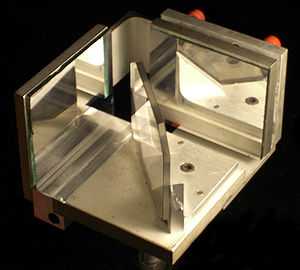

At the Jodrell Bank Observatory of Manchester University, Hanbury Brown developed some of the earliest devices to be used in radio astronomy. He worked closely with the mathematician Richard Q. Twiss on the development of, amongst other things, radio intensity interferometry and the first optical stellar intensity interferometer, using army surplus searchlights as infinity focused photon collectors. Using this instrument he became the first person to measure the angular diameter of the star Sirius. In 1962 he relocated to New South Wales in Australia to oversee the construction of the Narrabri Stellar Intensity Interferometer. Two years into the task he resigned from the chair that had been created for him at Manchester and took up an appointment at the University of Sydney. After the Narrabri interferometer was decommissioned in 1974, having completed its task (to measure the angular diameter of 32 main sequence stars), he stayed on in Sydney to design a next generation instrument. This was not to be another intensity interferometer, but a modernised Michelson interferometer. As Hanbury Brown himself was keen to emphasize, the development of this technologically exceedingly demanding instrument—the Sydney University Stellar Interferometer (SUSI) -- became essentially the project of his colleague John Davis (1932–2010).[5] The SUSI opened in 1991.

Brown died in Andover, Hampshire.

Honours and awards

In March, 1960 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London and in 1971 was awarded their Hughes Medal for " his efforts in developing the optical stellar intensity interferometer and for his observations of Spica".[6] In 1968, he received the Eddington Medal jointly with Twiss (see Hanbury Brown and Twiss effect). He also won the Thomas Ranken Lyle Medal of the Australian Academy of Science in 1972.[7] In 1982 he was named President of the International Astronomical Union, a title he retained until the end of his term in 1985. In 1986 he was made a Companion in the Order of Australia. He was awarded the Albert A. Michelson Medal of the Franklin Institute in 1982, jointly with Richard Q. Twiss.[8]

Publications

He wrote an autobiographical account of the development of airborne and ground based radar, and his subsequent work on radio astronomy. Since he was rumoured to have been the original boffin who inspired the term, he called these recollections Boffin: A Personal Story of the Early Days of Radar, Radio Astronomy and Quantum Optics

- Hanbury Brown and Twiss, A test of a new type of stellar interferometer on Sirius Nature, Vol. 178, pp. 1046 1956

- Hanbury Brown et al., The angular diameters of 32 stars Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc., Vol. 167, pp 121–136 1974

- Hanbury Brown, Boffin : A Personal Story of the Early Days of Radar, Radio Astronomy and Quantum Optics ISBN 0-7503-0130-9.

- Hanbury Brown, The Wisdom of Science - its relevance to Culture & Religion (ISBN 0-521-31448-8).

References

- ↑ Davis, J.; Lovell, B. (2003). "Robert Hanbury Brown. 31 August 1916 - 16 January 2002 Elected FRS 1960". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 49: 83. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2003.0005. JSTOR 3650215.

- ↑ Radhakrishnan, V. (July 2002). "Obituary: Robert Hanbury Brown". Physics Today 55 (7): 75–76. doi:10.1063/1.1506758.

- ↑ Papers and correspondence of Robert Hanbury Brown

- ↑ Lovell, Bernard; May, Robert M. (7 March 2002). "Obituary: Robert Hanbury Brown (1916–2002)". Nature 41: 34. doi:10.1038/416034a.

- ↑ Sydney Observatory, "In Memory – Emeritus Professor John Davis"

- ↑ "Library and Archive Catalog". Royal Society. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ↑ Thomas Ranken Lyle Medal, Australian Academy of Science, retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ↑ "Franklin Laureate Database - Albert A. Michelson Medal Laureates". Franklin Institute. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

Further reading

- D. Edge and M. Mulkay, Astronomy Transformed. The Emergence of Radio Astronomy in Britain (John Wiley, 1976)

- J. Agar, Science and Spectacle. The Work of Jodrell Bank in Postwar British Culture (Harwood Academic, 1997)

External links

- The papers of Robert Hanbury Brown have just been processed by the NCUACS, Bath, England . They can now be consulted in the Archives of the Royal Society.

| ||||||||||||||||||||