Ringing artifacts

In signal processing, particularly digital image processing, ringing artifacts are artifacts that appear as spurious signals near sharp transitions in a signal. Visually, they appear as bands or "ghosts" near edges; audibly, they appear as "echos" near transients, particularly sounds from percussion instruments; most noticeable are the pre-echos. The term "ringing" is because the output signal oscillates at a fading rate around a sharp transition in the input, similar to a bell after being struck. As with other artifacts, their minimization is a criterion in filter design.

Introduction

The main cause of ringing artifacts is due to a signal being bandlimited (specifically, not having high frequencies) or passed through a low-pass filter; this is the frequency domain description. In terms of the time domain, the cause of this type of ringing is the ripples in the sinc function,[1] which is the impulse response (time domain representation) of a perfect low-pass filter. Mathematically, this is called the Gibbs phenomenon.

One may distinguish overshoot (and undershoot), which occurs when transitions are accentuated – the output is higher than the input – from ringing, where after an overshoot, the signal overcorrects and is now below the target value; these phenomena often occur together, and are thus often conflated and jointly referred to as "ringing".

The term "ringing" is most often used for ripples in the time domain, though it is also sometimes used for frequency domain effects:[2] windowing a filter in the time domain by a rectangular function causes ripples in the frequency domain for the same reason as a brick-wall low pass filter (rectangular function in the frequency domain) causes ripples in the time domain, in each case the Fourier transform of the rectangular function being the sinc function.

There are related artifacts caused by other frequency domain effects, and similar artifacts due to unrelated causes.

Causes

Description

.svg.png)

By definition, ringing occurs when a non-oscillating input yields an oscillating output: formally, when an input signal which is monotonic on an interval has output response which is not monotonic. This occurs most severely when the impulse response or step response of a filter has oscillations – less formally, if for a spike input, respectively a step input (a sharp transition), the output has bumps. Ringing most commonly refers to step ringing, and that will be the focus.

Ringing is closely related to overshoot and undershoot, which is when the output takes on values higher than the maximum (respectively, lower than the minimum) input value: one can have one without the other, but in important cases, such as a low-pass filter, one first has overshoot, then the response bounces back below the steady-state level, causing the first ring, and then oscillates back and forth above and below the steady-state level. Thus overshoot is the first step of the phenomenon, while ringing is the second and subsequent steps. Due to this close connection, the terms are often conflated, with "ringing" referring to both the initial overshoot and the subsequent rings.

If one has a linear time invariant (LTI) filter, then one can understand the filter and ringing in terms of the impulse response (the time domain view), or in terms of its Fourier transform, the frequency response (the frequency domain view). Ringing is a time domain artifact, and in filter design is traded off with desired frequency domain characteristics: the desired frequency response may cause ringing, while reducing or eliminating ringing may worsen the frequency response.

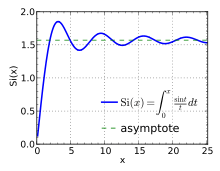

sinc filter

The central example, and often what is meant by "ringing artifacts", is the ideal (brick-wall) low-pass filter, the sinc filter. This has an oscillatory impulse response function, as illustrated above, and the step response – its integral, the Sine integral – thus also features oscillations, as illustrated at right.

These ringing artifacts are not results of imperfect implementation or windowing: the ideal low-pass filter, while possessing the desired frequency response, necessarily causes ringing artifacts in the time domain.

Time domain

In terms of impulse response, the correspondence between these artifacts and the behavior of the function is as follows:

- impulse undershoot is equivalent to the impulse response having negative values,

- impulse ringing (ringing near a point) is precisely equivalent to the impulse response having oscillations, which is equivalent to the derivative of the impulse response alternating between negative and positive values,

- and there is no notion of impulse overshoot, as the unit impulse is assumed to have infinite height (and integral 1 – a Dirac delta function), and thus cannot be overshot.

Turning to step response,

the step response is the integral of the impulse response; formally, the value of the step response at time a is the integral  of the impulse response. Thus values of the step response can be understood in terms of tail integrals of the impulse response.

of the impulse response. Thus values of the step response can be understood in terms of tail integrals of the impulse response.

Assume that the overall integral of the impulse response is 1, so it sends constant input to the same constant as output – otherwise the filter has gain, and scaling by gain gives an integral of 1.

- Step undershoot is equivalent to a tail integral being negative, in which case the magnitude of the undershoot is the value of the tail integral.

- Step overshoot is equivalent to a tail integral being greater than 1, in which case the magnitude of the overshoot is the amount by which the tail integral exceeds 1 – or equivalently the value of the tail in the other direction,

since these add up to 1.

since these add up to 1. - Step ringing is equivalent to tail integrals alternating between increasing and decreasing – taking derivatives, this is equivalent to the impulse response alternating between positive and negative values.[3] Regions where an impulse response are below or above the x-axis (formally, regions between zeros) are called lobes, and the magnitude of an oscillation (from peak to trough) equals the integral of the corresponding lobe.

The impulse response may have many negative lobes, and thus many oscillations, each yielding a ring, though these decay for practical filters, and thus one generally only sees a few rings, with the first generally being most pronounced.

Note that if the impulse response has small negative lobes and larger positive lobes, then it will exhibit ringing but not undershoot or overshoot: the tail integral will always be between 0 and 1, but will oscillate down at each negative lobe. However, in the sinc filter, the lobes monotonically decrease in magnitude and alternate in sign, as in the alternating harmonic series, and thus tail integrals alternate in sign as well, so it exhibits overshoot as well as ringing.

Conversely, if the impulse response is always nonnegative, so it has no negative lobes – the function is a probability distribution – then the step response will exhibit neither ringing nor overshoot or undershoot – it will be a monotonic function growing from 0 to 1, like a cumulative distribution function. Thus the basic solution from the time domain perspective is to use filters with nonnegative impulse response.

Frequency domain

The frequency domain perspective is that ringing is caused by the sharp cut-off in the rectangular passband in the frequency domain, and thus is reduced by smoother roll-off, as discussed below.[1][4]

Solutions

Solutions depend on the parameters of the problem: if the cause is a low-pass filter, one may choose a different filter design, which reduces artifacts at the expense of worse frequency domain performance. On the other hand, if the cause is a band-limited signal, as in JPEG, one cannot simply replace a filter, and ringing artifacts may prove hard to fix – they are present in JPEG 2000 and many audio compression codecs (in the form of pre-echo), as discussed in the examples.

Low-pass filter

If the cause is the use of a brick-wall low-pass filter, one may replace the filter with one that reduces the time domain artifacts, at the cost of frequency domain performance. This can be analyzed from the time domain or frequency domain perspective.

In the time domain, the cause is an impulse response that oscillates, assuming negative values. This can be resolved by using a filter whose impulse response is non-negative and does not oscillate, but shares desired traits. For example, for a low-pass filter, the Gaussian filter is non-negative and non-oscillatory, hence causes no ringing. However, it is not as good as a low-pass filter: it rolls off in the passband, and leaks in the stopband: in image terms, a Gaussian filter "blurs" the signal, which reflects the attenuation of desired higher frequency signals in the passband.

A general solution is to use a window function on the sinc filter, which cuts off or reduces the negative lobes: these respectively eliminate and reduce overshoot and ringing. Note that truncating some but not all of the lobes eliminates the ringing beyond that point, but does not reduce the amplitude of the ringing that is not truncated (because this is determined by the size of the lobe), and increases the magnitude of the overshoot if the last non-cut lobe is negative, since the magnitude of the overshoot is the integral of the tail, which is no longer canceled by positive lobes.

Further, in practical implementations one at least truncates sinc, otherwise one must use infinitely many data points (or rather, all points of the signal) to compute every point of the output – truncation corresponds to a rectangular window, and makes the filter practically implementable, but the frequency response is no longer perfect.[5]

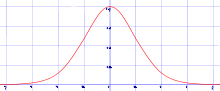

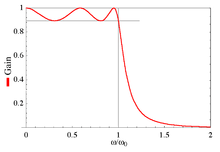

In fact, if one takes a brick wall low-pass filter (sinc in time domain, rectangular in frequency domain) and truncates it (multiplies with a rectangular function in the time domain), this convolves the frequency domain with sinc (Fourier transform of the rectangular function) and causes ringing in the frequency domain,[2] which is referred to as ripple. In symbols,  The frequency ringing in the stopband is also referred to as side lobes. Flat response in the passband is desirable, so one windows with functions whose Fourier transform has fewer oscillations, so the frequency domain behavior is better.

The frequency ringing in the stopband is also referred to as side lobes. Flat response in the passband is desirable, so one windows with functions whose Fourier transform has fewer oscillations, so the frequency domain behavior is better.

Multiplication in the time domain corresponds to convolution in the frequency domain, so multiplying a filter by a window function corresponds to convolving the Fourier transform of the original filter by the Fourier transform of the window, which has a smoothing effect – thus windowing in the time domain corresponds to smoothing in the frequency domain, and reduces or eliminates overshoot and ringing.[6]

In the frequency domain, the cause can be interpreted as due to the sharp (brick-wall) cut-off, and ringing reduced by using a filter with smoother roll-off.[1] This is the case for the Gaussian filter, whose magnitude Bode plot is a downward opening parabola (quadratic roll-off), as its Fourier transform is again a Gaussian, hence (up to scale)  – taking logarithms yields

– taking logarithms yields

|

|

In electronic filters, the trade-off between frequency domain response and time domain ringing artifacts is well-illustrated by the Butterworth filter: the frequency response of a Butterworth filter slopes down linearly on the log scale, with a first-order filter having slope of −6 dB per octave, a second-order filter –12 dB per octave, and an nth order filter having slope of  dB per octave – in the limit, this approaches a brick-wall filter. Thus, among these the, first-order filter rolls off slowest, and hence exhibits the fewest time domain artifacts, but leaks the most in the stopband, while as order increases, the leakage decreases, but artifacts increase.[4]

dB per octave – in the limit, this approaches a brick-wall filter. Thus, among these the, first-order filter rolls off slowest, and hence exhibits the fewest time domain artifacts, but leaks the most in the stopband, while as order increases, the leakage decreases, but artifacts increase.[4]

Benefits

While ringing artifacts are generally considered undesirable, the initial overshoot (haloing) at transitions increases acutance (apparent sharpness) by increasing the derivative across the transition, and thus can be considered as an enhancement.[8]

Related phenomena

Overshoot

.svg.png)

Another artifact is overshoot (and undershoot), which manifests itself not as rings, but as an increased jump at the transition. It is related to ringing, and often occurs in combination with it.

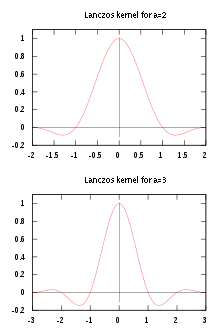

Overshoot and undershoot are caused by a negative tail – in the sinc, the integral from the first zero to infinity, including the first negative lobe. While ringing is caused by a following positive tail – in sinc, the integral from the second zero to infinity, including the first non-central positive lobe. Thus overshoot is necessary for ringing, but can occur separately: for example, the 2-lobed Lanczos filter has only a single negative lobe on each side, with no following positive lobe, and thus exhibits overshoot but no ringing, while the 3-lobed Lanczos filter exhibits both overshoot and ringing, though the windowing reduces this compared to the sinc filter or the truncated sinc filter.

Similarly, the convolution kernel used in bicubic interpolation is similar to a 2-lobe windowed sinc, taking on negative values, and thus produces overshoot artifacts, which appear as halos at transitions.

Clipping

Following from overshoot and undershoot is clipping. If the signal is bounded, for instance an 8-bit or 16-bit integer, this overshoot and undershoot can exceed the range of permissible values, thus causing clipping.

Strictly speaking, the clipping is caused by the combination of overshoot and limited numerical accuracy, but it is closely associated with ringing, and often occurs in combination with it.

Clipping can also occur for unrelated reasons, from a signal simply exceeding the range of a channel.

Ringing and ripple

In signal processing and related fields, the general phenomenon of time domain oscillation is called ringing, while frequency domain oscillations are generally called ripple, though generally not "rippling".

A key source of ripple in digital signal processing is the use of window functions: if one takes an infinite impulse response (IIR) filter, such as the sinc filter, and windows it to make it have finite impulse response, as in the window design method, then the frequency response of the resulting filter is the convolution of the frequency response of the IIR filter with the frequency response of the window function. Notably, the frequency response of the rectangular filter is the sinc function (the rectangular function and the sinc function are Fourier dual to each other), and thus truncation of a filter in the time domain corresponds to multiplication by the rectangular filter, thus convolution by the sinc filter in the frequency domain, causing ripple. In symbols, the frequency response of  is

is  In particular, truncating the sinc function itself yields

In particular, truncating the sinc function itself yields  in the time domain, and

in the time domain, and  in the frequency domain, so just as low-pass filtering (truncating in the frequency domain) causes ringing in the time domain, truncating in the time domain (windowing by a rectangular filter) causes ripple in the frequency domain.

in the frequency domain, so just as low-pass filtering (truncating in the frequency domain) causes ringing in the time domain, truncating in the time domain (windowing by a rectangular filter) causes ripple in the frequency domain.

Examples

JPEG

JPEG compression can introduce ringing artifacts at sharp transitions, which are particularly visible in text.

This is a due to loss of high frequency components, as in step response ringing. JPEG uses 8×8 blocks, on which the discrete cosine transform (DCT) is performed. The DCT is a Fourier-related transform, and ringing occurs because of loss of high frequency components or loss of precision in high frequency components.

They can also occur at the edge of an image: since JPEG splits images into 8×8 blocks, if an image is not an integer number of blocks, the edge cannot easily be encoded, and solutions such as filling with a black border create a sharp transition in the source, hence ringing artifacts in the encoded image.

Ringing also occurs in the wavelet-based JPEG 2000.

JPEG and JPEG 2000 have other artifacts, as illustrated above, such as blocking ("jaggies") and edge busyness ("mosquito noise"), though these are due to specifics of the formats, and are not ringing as discussed here.

Some illustrations:

| Image | Lossless compression | Lossy compression |

|---|---|---|

| Original |  |  |

| Processed by Canny edge detector, highlighting artifacts. |

|  |

Pre-echo

In audio signal processing, ringing can causes echoes to occur before and after transients, such as the impulsive sound from percussion instruments, such as cymbals (this is impulse ringing). The (causal) echo after the transient is not heard, because it is masked by the transient, an effect called temporal masking. Thus only the (anti-causal) echo before the transient is heard, and the phenomenon is called pre-echo.

This phenomenon occurs as a compression artifact in audio compression algorithms that use Fourier-related transforms, such as MP3, AAC, and Vorbis.

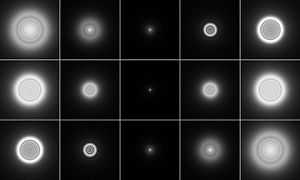

Similar phenomena

Other phenomena have similar symptoms to ringing, but are otherwise distinct in their causes. In cases where these cause circular artifacts around point sources, these may be referred to as "rings" due to the round shape (formally, an annulus), which is unrelated to the "ringing" (oscillatory decay) frequency phenomenon discussed on this page.

Edge enhancement

Edge enhancement, which aims to increase edges, may cause ringing phenomena, particularly under repeated application, such as by a DVD player followed by a television. This may be done by high-pass filtering, rather than low-pass filtering.[4]

Special functions

Many special functions exhibit oscillatory decay, and thus convolving with such a function yields ringing in the output; one may consider these ringing, or restrict the term to unintended artifacts in frequency domain signal processing.

Fraunhofer diffraction yields the Airy disk as point spread function, which has a ringing pattern.

.svg.png)

The Bessel function of the first kind,  which is related to the Airy function, exhibits such decay.

which is related to the Airy function, exhibits such decay.

In cameras, a combination of defocus and spherical aberration can yield circular artifacts ("ring" patterns). However, the pattern of these artifacts need not be similar to ringing (as discussed on this page) – they may exhibit oscillatory decay (circles of decreasing intensity), or other intensity patterns, such as a single bright band.

Interference

Ghosting is a form of television interference where an image in repeated, though this is not ringing; it can be interpreted as convolution with a function which is 1 at the origin and ε (the intensity of the ghost) at some distance, which is formally similar to the above functions (a single discrete peak, rather than continuous oscillation).

Lens flare

In photography, lens flare is a defect where various circles can appear around highlights, and with ghosts throughout a photo, due to undesired light, such as reflection and scattering off elements in the lens.

Visual illusions

Visual illusions can occur at transitions, as in Mach bands, which perceptually exhibit a similar undershoot/overshoot to the Gibbs phenomenon.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Bankman, Isaac N. (2000), Handbook of medical imaging, Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-077790-7, section I.6, Enhancement: Frequency Domain Techniques, p. 16

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Digital Signal Processing, by J.S.Chitode, Technical Publications, 2008, ISBN 978-81-8431-346-8, 4 - 70

- ↑ Glassner, Andrew S (2004), Principles of Digital Image Synthesis (2 ed.), Morgan Kaufmann, ISBN 978-1-55860-276-2, p. 518

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Microscope Image Processing, by Qiang Wu, Fatima Merchant, Kenneth Castleman, ISBN 978-0-12-372578-3 p. 71

- ↑ (Allen & Mills 2004) Section 9.3.1.1 Ideal Filters: Low pass, p. 621

- ↑ (Allen & Mills 2004) p. 623

- ↑ Op Amp applications handbook, by Walter G. Jung, Newnes, 2004, ISBN 978-0-7506-7844-5, p. 332

- ↑ Mitchell, Don P.; Netravali, Arun N. (August 1988). "Reconstruction filters in computer-graphics". ACM SIGGRAPH International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques 22 (4). pp. 221–228. doi:10.1145/54852.378514. ISBN 0-89791-275-6.

- Allen, Ronald L.; Mills, Duncan W. (2004), Signal analysis: time, frequency, scale, and structure, Wiley-IEEE, ISBN 978-0-471-23441-8