Rhumb line

In navigation, a rhumb line (or loxodrome) is a line crossing all meridians of longitude at the same angle, i.e. a path derived from a defined initial bearing. That is, upon taking an initial bearing, one proceeds along the same bearing, without changing the direction as measured relative to true or magnetic north.

Introduction

The effect of following a rhumb line course on the surface of a globe was first discussed by the Portuguese mathematician Pedro Nunes in 1537, in his Treatise in Defense of the Marine Chart, with further mathematical development by Thomas Harriot in the 1590s.

A rhumb line can be contrasted with a great circle, which is the path of shortest distance between two points on the surface of a sphere, but whose bearing is non-constant. If you were to drive a car along a great circle you would hold the steering wheel fixed, but to follow a rhumb line you would have to turn the wheel, turning it more sharply as the poles are approached. In other words, a great circle is locally "straight" with zero geodesic curvature, whereas a rhumb line has non-zero geodesic curvature.

Meridians of longitude and parallels of latitude provide special cases of the rhumb line, where their angles of intersection are respectively 0° and 90°. On a North-South passage the rhumb line course coincides with a great circle, as it does on an East-West passage along the equator.

On a Mercator projection map, a rhumb line is a straight line; a rhumb line can be drawn on such a map between any two points on Earth without going off the edge of the map. But theoretically a loxodrome can extend beyond the right edge of the map, where it then continues at the left edge with the same slope (assuming that the map covers exactly 360 degrees of longitude).

Rhumb lines which cut meridians at oblique angles are loxodromic curves which spiral towards the poles.[1] On a Mercator projection the North and South poles occur at infinity and are therefore never shown. However the full loxodrome on an infinitely high map would consist of infinitely many line segments between the two edges. On a stereographic projection map, a loxodrome is an equiangular spiral whose center is the North (or South) Pole.

All loxodromes spiral from one pole to the other. Near the poles, they are close to being logarithmic spirals (on a stereographic projection they are exactly, see below), so they wind round each pole an infinite number of times but reach the pole in a finite distance. The pole-to-pole length of a loxodrome is (assuming a perfect sphere) the length of the meridian divided by the cosine of the bearing away from true north. Loxodromes are not defined at the poles.

- Three views of a pole-to-pole loxodrome

-

-

-

Etymology and historical description

The word "loxodrome" comes from Greek loxos : oblique + dromos : running (from dramein : to run). The word "rhumb" may come from Spanish/Portuguese rumbo/rumo (course, direction) and Greek ῥόμβος.[2]

The 1878 edition ofThe Globe Encyclopaedia of Universal Information describes loxodrome lines as:[3]

- Loxodrom'ic Line is a curve which cuts every member of a system of lines of curvature of a given surface at the same angle. A ship sailing towards the same point of the compass describes such a line which cuts all the meridians at the same angle. In Mercator's Projection (q.v.) the Loxodromic lines are evidently straight.[3]

Mathematical definition

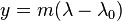

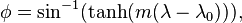

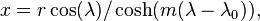

Let β be the constant bearing from true north of the loxodrome and  be the longitude where the loxodrome passes the equator.[4] Let

be the longitude where the loxodrome passes the equator.[4] Let  be the longitude of a point on the loxodrome. Under the Mercator projection the loxodrome will be a straight line

be the longitude of a point on the loxodrome. Under the Mercator projection the loxodrome will be a straight line

with slope  . For a point with latitude

. For a point with latitude  and longitude

and longitude  the position in the Mercator projection can be expressed as

the position in the Mercator projection can be expressed as

Then the latitude of the point will be

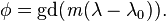

or in terms of the Gudermannian function gd  In cartesian coordinates this can be simplified to

In cartesian coordinates this can be simplified to

Finding the loxodromes between two given points can be done graphically on a Mercator map, or by solving a nonlinear system of two equations in the two unknowns tan(α) and λ0. There are infinitely many solutions; the shortest one is that which covers the actual longitude difference, i.e. does not make extra revolutions, and does not go "the wrong way around".

The distance between two points, measured along a loxodrome, is simply the absolute value of the secant of the bearing (azimuth) times the north-south distance (except for circles of latitude for which the distance becomes infinite).

The above formulas assume a spherical earth; the formulas for the spheroid are of course more complicated, but not hopelessly so.

Application

Its use in navigation is directly linked to the style, or projection of certain navigational maps. A rhumb line appears as a straight line on a Mercator projection map.[1]

The name is derived from Old French or Spanish respectively: "rumb" or "rumbo", a line on the chart which intersects all meridians at the same angle.[1] On a plane surface this would be the shortest distance between two points. Over the Earth's surface at low latitudes or over short distances it can be used for plotting the course of a vehicle, aircraft or ship.[1] Over longer distances and/or at higher latitudes the great circle route is significantly shorter than the rhumb line between the same two points. However the inconvenience of having to continuously change bearings while travelling a great circle route makes rhumb line navigation appealing in certain instances.[1]

The point can be illustrated with an East-West passage over 90 degrees of longitude along the equator, for which the great circle and rhumb line distances are the same at 5,400 nautical miles (10,000 km). At 20 degrees North the great circle distance is 4,997 miles (8,042 km) while the rhumb line distance is 5,074 miles (8,166 km), about 1½ percent further. But at 60 degrees North the great circle distance is 2,485 miles (3,999 km) while the rhumb line is 2,700 miles (4,300 km), a difference of 8½ percent. A more extreme case is the air route between New York and Hong Kong, for which the rhumb line path is 9,700 nautical miles (18,000 km). The great circle route over the North Pole is 7,000 nautical miles (13,000 km), or 5½ hours less flying time at a typical cruising speed.

Some old maps in the Mercator projection have grids composed of lines of latitude and longitude but also show rhumb lines which are oriented directly towards North, at a right angle from the North, or at some angle from the North which is some simple rational fraction of a right angle. These rhumb lines would be drawn so that they would converge at certain points of the map: lines going in every direction would converge at each of these points. See compass rose. Such maps would necessarily have been in the Mercator projection therefore not all old maps would have been capable of showing rhumb line markings.

The radial lines on a compass rose are also called rhumbs. The expression "sailing on a rhumb" was used in the 16th–19th centuries to indicate a particular compass heading.[1]

Early navigators in the time before the invention of the chronometer used rhumb line courses on long ocean passages, because the ship's latitude could be established accurately by sightings of the Sun or stars but there was no accurate way to determine the longitude. The ship would sail North or South until the latitude of the destination was reached, and the ship would then sail East or West along the rhumb line (actually a parallel, which is a special case of the rhumb line), maintaining a constant latitude and recording regular estimates of the distance sailed until evidence of land was sighted.[5]

Generalizations

On the Riemann sphere

The surface of the earth can be understood mathematically as a Riemann sphere, that is, as a projection of the sphere to the complex plane. In this case, loxodromes can be understood as certain classes of Möbius transformations.

Spheroid

The formulation above can be extended for a spheroid; see, e.g.,.[6]

See also

- Great circle

- Small circle

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Oxford University Press Rhumb Line. The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea, Oxford University Press, 2006. Retrieved from Encyclopedia.com 18 July 2009.

- ↑ Rhumb at TheFreeDictionary

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ross, J.M. (editor) (1878). "The Globe Encyclopaedia of Universal Information", Vol. IV, Edinburgh-Scotland, Thomas C. Jack, Grange Publishing Works, retrieved from Google Books 2009-03-18;

- ↑ James Alexandre, Loxodromes: A Rhumb Way to Go, "Mathematics Magazine", Vol. 77. No. 5, Dec. 2004.

- ↑ A Brief History of British Seapower, David Howarth, pub. Constable & Robinson, London, 2003, chapter 8.

- ↑ Hoffman-Wellenhof et at. (2003) Navigation

External links

- Constant Headings and Rhumb Lines at MathPages

Note: this article incorporates text from the 1878 edition of The Globe Encyclopaedia of Universal Information, a work in the public domain