Republic of Kosovo

| Republic of Kosovo |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

Anthem: Europe [1] |

||||||

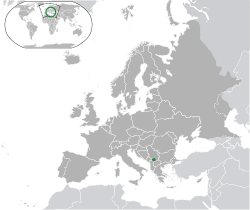

Location and extent of Kosovo in Europe.

|

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Pristina 42°40′N 21°10′E / 42.667°N 21.167°E | |||||

| Official languages | ||||||

| Recognised regional languages | ||||||

| Demonym |

|

|||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | |||||

| - | President | Atifete Jahjaga | ||||

| - | Chairman of the Assembly | Jakup Krasniqi | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Hashim Thaçi | ||||

| Legislature | Assembly of Kosovo | |||||

| Establishment | ||||||

| - | Republic of Kosova | 2 July 1990 | ||||

| - | UN Security Council Resolution 1244 | 10 June 1999 | ||||

| - | Independence from Serbia | 11 June 1999 | ||||

| - | UN-administered Kosovo | June 1999 | ||||

| - | Republic of Kosovo | 17 February 2008 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 10,908 km2 4,212 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | n/a | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2011 estimate | 1,733,842b | ||||

| - | 1991 census | 1,956,196c | ||||

| - | Density | 159/km2 412/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2011 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $12.859 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $7,043 | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2011 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $6.452 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $3,721 | ||||

| Gini | 30.0[3] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2012) | high |

|||||

| Currency | Euro (€)d (EUR) |

|||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +381e | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | XK | |||||

| a. | Only partially recognised internationally. | |||||

| b. | Preliminary results of 2011 census, which excluded four northern Serb-majority municipalities where it could not be carried out. | |||||

| c. | This census is a reconstruction, as it was mostly boycotted by the ethnic Albanian majority. | |||||

| d. | Adopted unilaterally; Kosovo is not a formal member of the eurozone. | |||||

| e. | +381 for fixed lines; Kosovo-licenced mobile-phone providers use +377 (Monaco) or +386 (Slovenia) instead. +383 from 2015. | |||||

| f. | XK is a "user assigned" ISO 3166 code not designated by the standard, but used by European Commission, Switzerland, the Deutsche Bundesbank and other organisations. | |||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Kosovo |

|---|

|

| Early History |

|

| Middle Ages |

|

| Ottoman Kosovo |

| 20th century |

|

| Recent history |

| See also |

|

|

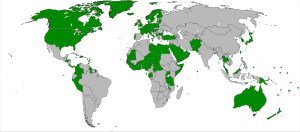

The Republic of Kosovo /ˈkɒsəvoʊ, -ˈkoʊ-/[5] (Albanian: Republika e Kosovës; Serbian: Република Косово / Republika Kosovo) is the Government and Civil authority administering all of the region of Kosovo in the Balkan Peninsula of Southeastern Europe and is recognised as a sovereign state by 108 UN member states, though its status is disputed. Its largest city and capital is Pristina. Kosovo is landlocked and is bordered by the Republic of Macedonia to the south, Albania to the west and Montenegro to the northwest. The nature of the remaining line of demarcation is the subject of controversy — seen by proponents of Kosovan independence as the Kosovo-Serbia border and seen by opponents of the independence as the boundary between Central Serbia and the claimed Serbian Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija.[6] Kosovo institutions have control over all of the country as the Brussels agreement abolished all Belgrade's institutions. Pristina now appoints the police commander of north Kosovo, upon proposal of the Kosovo Serb community, and has complete power in judicial matters.

After a failure to produce results from non-violent resistance to Serbian rule from 1990,[7] and an armed insurgency by Albanians from 1997–99, NATO launched a 78-day assault on FR Yugoslavia to halt the war in Kosovo. In 1999 the United Nations through UNMIK began overseeing the administration of the province after a UN Security Council (UNSC) resolution. On 17 February 2008 Kosovo's Parliament declared independence, as the "Republic of Kosovo", which has received recognition from some sovereign states. With the Brussels agreement Serbia recognized the secession of Kosovo and its autonomy from Serbia but does not formally recognize it as an independent country.

The Republic of Kosovo has been recognised by 108 UN member states and is a member of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, International Road and Transport Union (IRU), Regional Cooperation Council, Council of Europe Development Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.[8] 23 of 28 countries of the European Union have recognised the Republic of Kosovo.

History

Disintegration of Yugoslavia

Inter-ethnic tensions continued to worsen in Kosovo throughout the 1980s. The 1986 Memorandum of the Serbian Academy warned that Yugoslavia was suffering from ethnic strife and the disintegration of the Yugoslav economy into separate economic sectors and territories, which was transforming the federal state into a loose confederation.[9]

On 28 June 1989, Slobodan Milošević delivered the Gazimestan speech in front of a large number of ethnic Serbs at the main celebration marking the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo at the Gazimestan. Many think that this speech helped Milošević consolidate his authority in Serbia.[10] In 1989, Milošević, employing a mix of intimidation and political manoeuvring, drastically reduced Kosovo's special autonomous status within Serbia and started cultural oppression of the ethnic Albanian population.[11] Kosovo Albanians responded with a non-violent separatist movement, employing widespread civil disobedience and creation of parallel structures in education, medical care, and taxation, with the ultimate goal of achieving the independence of Kosovo.[12]

On 2 July 1990 a majority of members of the Kosovo Assembly passed a resolution declaring the Republic of Kosova within the Yugoslav Federation; in September 1991 (after the dissolution of the Assembly by Serbia) they passed a Constitution which would have given the Republic effective sovereignty but which might have also been compatible with a Yugoslav confederation if this had existed; in September 1992 they declared the Republic a sovereign and independent state.[13] In May 1992, Ibrahim Rugova was elected president.[14] During its lifetime, the Republic of Kosova was only officially recognised by Albania; it was formally disbanded in 2000, after the Kosovo War, when its institutions were replaced by the Joint Interim Administrative Structure established by the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK).

Kosovo War

In 1995 the Dayton Agreement ended the Bosnian War, drawing considerable international attention. However, despite the hopes of Kosovar Albanians, the situation in Kosovo remained largely un-addressed by the international community, and by 1996 the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), an ethnic Albanian guerrilla paramilitary group, had prevailed over the non-violent resistance movement and had started offering armed resistance to Serbian and Yugoslav security forces, resulting in early stages of the Kosovo War.[11][15]

By 1998, as the violence had worsened and displaced scores of Albanians, Western interest had increased. The Serbian authorities were compelled to sign a ceasefire and partial retreat, monitored by Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) observers according to an agreement negotiated by Richard Holbrooke. However, the ceasefire did not hold and fighting resumed in December 1998. The Račak massacre in January 1999 in particular brought new international attention to the conflict.[11] Within weeks, a multilateral international conference was convened and by March had prepared a draft agreement known as the Rambouillet Accords, calling for restoration of Kosovo's autonomy and deployment of NATO peacekeeping forces. The Serbian party found the terms unacceptable and refused to sign the draft.

Between 24 March and 10 June 1999, NATO intervened by bombing Yugoslavia aimed to force Milošević to withdraw his forces from Kosovo,[16] though NATO could not appeal to any particular motion of the Security Council of the United Nations to help legitimise its intervention. Combined with continued skirmishes between Albanian guerrillas and Yugoslav forces the conflict resulted in a further massive displacement of population in Kosovo.[17]

During the conflict, roughly a million ethnic Albanians fled or were forcefully driven from Kosovo. In 1999 more than 11,000 deaths were reported to Carla Del Ponte by her prosecutors.[18] Some 3,000 people are still missing, of which 2,500 are Albanian, 400 Serbs and 100 Roma.[19] Ultimately by June, Milošević had agreed to a foreign military presence within Kosovo and withdrawal of his troops.

Since May 1999, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia has prosecuted crimes committed during the Kosovo War. Nine Serbian and Yugoslavian commanders have been indicted so far for crimes against humanity and violations of the laws or customs of war in Kosovo in 1999: Yugoslavian President Slobodan Milošević, Serbian President Milan Milutinović, Yugoslavian Deputy Prime Minister Nikola Šainović, Yugoslavian Chief of the General Staff Gen. Dragoljub Ojdanić, Serbian Interior Minister Vlajko Stojiljković, Gen. Nebojša Pavković, Gen. Vladimir Lazarević, Deputy Interior Minister of Serbia Vlastimir Đorđević and Chief of the Interior for Kosovo Sreten Lukić. Stojiljković killed himself while at large in 2002 and Milošević died in custody during the trial in 2006. In 2009 Milutinovic was acquitted by the Trial Chamber; five defendants were found guilty (three sentenced to 15 years imprisonment, and two to 22 years; and in 2011 the remaining defendant, who had been in hiding when the main trial started, was found guilty and sentenced to 27 years.[20] The verdicts are under appeal. The indictment against the nine alleged that they directed, encouraged or supported a campaign of terror and violence directed at Kosovo Albanian civilians and aimed at the expulsion of a substantial portion of them from Kosovo. It has been alleged that about 800,000 Albanians were expelled as a result. In particular, in the indictment of June 2006, the accused were charged with the murder of 919 identified Kosovo Albanian civilians aged from one to 93, both male and female.[21][22][23][24]

In addition, the Office of the Serbian War Crimes Prosecutor has secured final judgements involving the conviction of 7 persons, sentenced to a total of 136 years imprisonment for war crimes in Kosovo involving 89 Albanian victims. As of June 2012, a trial of 12 defendants for an alleged massacre of 44 Albanian victims in Čuška (Alb: Qyshk) is ongoing.[25]

Six KLA commanders were indicted by ICTY in two cases: Fatmir Limaj, Isak Musliu and Haradin Bala,[26] as well as Ramush Haradinaj, Idriz Balaj and Lahi Brahimaj. They were charged with crimes against humanity and violations of the laws and customs of war in Kosovo in 1998, consisting in persecutions, cruel treatment, torture, murders and rape of several dozens of the local Serbs, Albanians and other civilians perceived un-loyal to the KLA. In particular, Limaj, Musliu and Bala were accused of murder of 22 identified detainees at or near the Lapušnik Prison Camp. In 2005 Limaj and Musliu were found not guilty on all charges, Bala was found guilty of persecutions, cruel treatment, murders and rape and sentenced to 13 years. The appeal chamber affirmed the judgements in 2007. In 2008 Ramush Haradinaj and Idriz Balaj were acquitted, whereas Lahi Brahimaj was found guilty of cruel treatment and torture and sentenced to six years.[27][28][29] The Office of the Prosecutor appealed their acquittals, resulting in the ICTY ordering a partial retrial; however on 29 November 2012 all three were acquitted of all charges.[30]

UN administration period

On 10 June 1999, the UN Security Council passed UN Security Council Resolution 1244, which placed Kosovo under transitional UN administration (UNMIK) and authorised Kosovo Force (KFOR), a NATO-led peacekeeping force. Resolution 1244 provided that Kosovo would have autonomy within the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and affirmed the territorial integrity of Yugoslavia, which has been legally succeeded by the Republic of Serbia.[31]

Estimates of the number of Serbs who left when Serbian forces left Kosovo vary from 65,000 [32] to 250,000[33] (194,000 Serbs were recorded as living in Kosovo in the census of 1991. But many Roma also left and may be included in the higher estimates). The majority of Serbs who left were from urban areas, but Serbs who stayed (whether in urban or rural areas) suffered violence which largely (but not entirely) ceased between early 2001 and the riots of March 2004, and ongoing fears of harassment may be a factor deterring their return. International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo, as envisaged under UN Security Council Resolution 1244. The UN-backed talks, led by UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, began in February 2006. Whilst progress was made on technical matters, both parties remained diametrically opposed on the question of status itself.[34]

In February 2007, Ahtisaari delivered a draft status settlement proposal to leaders in Belgrade and Pristina, the basis for a draft UN Security Council Resolution which proposed 'supervised independence' for the province. A draft resolution, backed by the United States, the United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council, was presented and rewritten four times to try to accommodate Russian concerns that such a resolution would undermine the principle of state sovereignty.[35]

Russia, which holds a veto in the Security Council as one of five permanent members, had stated that it would not support any resolution which was not acceptable to both Belgrade and Kosovo Albanians.[36] Whilst most observers had, at the beginning of the talks, anticipated independence as the most likely outcome, others have suggested that a rapid resolution might not be preferable.[37]

After many weeks of discussions at the UN, the United States, United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council formally 'discarded' a draft resolution backing Ahtisaari's proposal on 20 July 2007, having failed to secure Russian backing. Beginning in August, a "Troika" consisting of negotiators from the European Union (Wolfgang Ischinger), the United States (Frank G. Wisner) and Russia (Alexander Botsan-Kharchenko) launched a new effort to reach a status outcome acceptable to both Belgrade and Pristina. Despite Russian disapproval, the U.S., the United Kingdom, and France appeared likely to recognise Kosovar independence.[38] A declaration of independence by Kosovar Albanian leaders was postponed until the end of the Serbian presidential elections (4 February 2008). Most EU members and the US had feared that a premature declaration could boost support in Serbia for the ultra-nationalist candidate, Tomislav Nikolić.[39]

Under the Constitutional Framework, Kosovo had a 120-member Kosovo Assembly. The Assembly includes twenty reserved seats: ten for Kosovo Serbs and ten for non-Serb and non-Albanian nations (e.g. Bosniaks, Roma, etc.). The Kosovo Assembly was responsible for electing the President, Prime Minister, and Government of Kosovo, and for passing legislation which was vetted and promulgated by UNMIK.

Provisional institutions of self-government

In November 2001, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe supervised the first elections for the Kosovo Assembly.[40] After that election, Kosovo's political parties formed an all-party unity coalition and elected Ibrahim Rugova as President and Bajram Rexhepi (PDK) as Prime Minister.[41] After Kosovo-wide elections in October 2004, the LDK and AAK formed a new governing coalition that did not include PDK and Ora. This coalition agreement resulted in Ramush Haradinaj (AAK) becoming Prime Minister, while Ibrahim Rugova retained the position of President. PDK and Ora were critical of the coalition agreement and have since frequently accused that government of corruption.[42]

Parliamentary elections were held on 17 November 2007. After early results, Hashim Thaçi who was on course to gain 35 per cent of the vote, claimed victory for PDK, the Democratic Party of Kosovo, and stated his intention to declare independence. Thaçi formed a coalition with current President Fatmir Sejdiu's Democratic League which was in second place with 22 percent of the vote.[43] The turnout at the election was particularly low. Most members of the Serb minority refused to vote.[44]

However, since 1999, North Kosovo has remained largely outside the control of the Kosovo Government.

Declaration of independence

Kosovo declared independence on 17 February 2008[45] and over the following days, a number of states (the United States, Turkey, Albania, Austria, Croatia, Germany, Italy, France, the United Kingdom, the Republic of China (Taiwan),[46] Australia, Poland and others) announced their recognition, despite protests by Russia and others in the UN.[47] As of 11 February 2014, 108 UN states recognise the independence of Kosovo and it has become a member country of the IMF and World Bank as the Republic of Kosovo.[48][49] The ICJ concluded unanimously in 2010 that Kosovo's declaration of independence of 17 February 2008 did not violate general international law.[50]

The UN Security Council remains divided on the question (as of 4 July 2008). Of the five members with veto power, USA, UK, and France recognised the declaration of independence, and the People's Republic of China has expressed concern, while Russia considers it illegal. As of May 2010, no member-country of Commonwealth of Independent States, Collective Security Treaty Organisation or Shanghai Cooperation Organisation has recognised Kosovo as independent. Kosovo has not made a formal application for UN membership yet in view of a possible veto from Russia and China.[citation needed]

The European Union has no official position towards Kosovo's status, but has decided to deploy the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo to ensure a continuation of international civil presence in Kosovo. As of December 2013, most of the member-countries of NATO, EU, Western European Union and OECD have recognised Kosovo as independent.[51]

All of Kosovo's immediate neighbour states except Serbia have recognised the declaration of independence. Montenegro and Macedonia announced their recognition of Kosovo on 9 October 2008.[52] Albania, Croatia, Bulgaria and Hungary have also recognised the independence of Kosovo.[53]

The Serb minority of Kosovo, which largely opposes the declaration of independence, has formed the Community Assembly of Kosovo and Metohija in response. The creation of the assembly was condemned by Kosovo's president Fatmir Sejdiu, while UNMIK has said the assembly is not a serious issue because it will not have an operative role.[54] On 8 October 2008, the UN General Assembly resolved, on a proposal by Serbia, to ask the International Court of Justice to render an advisory opinion on the legality of Kosovo's declaration of independence. The advisory opinion, which is not binding over decisions by states to recognise or not recognise Kosovo, was rendered on 22 July 2010, holding that Kosovo's declaration of independence was not in violation either of general principles of international law, which do not prohibit unilateral declarations of independence, nor of specific international law - in particular UNSCR 1244 - which did not define the final status process nor reserve the outcome to a decision of the Security Council.[55]

Some rapprochement between the two governments took place on 19 April 2013 as both parties reached an EU brokered agreement that would allow the Serb minority in Kosovo to have its own police force and court of appeals.[56] However, the agreement is yet to be ratified by parliaments in both countries.[57]

Government and politics

Government

The government of the Republic of Kosovo is defined under the 2008 Constitution of Kosovo as a multi-party parliamentary representative democratic republic. Legislative power is vested in both the Assembly of Kosovo and the ministers within their competencies. The President of Kosovo is the head of state and represents the "unity of the people". The Executive of Kosovo exercises the executive power and is composed of the Prime Minister of Kosovo as the head of government, the deputy prime ministers, and the ministers of the various ministries. The legal system is composed of an independent judiciary composed of the Supreme Court and subordinate courts, a Constitutional Court, and an independent prosecutorial institution. There also exist multiple independent institutions defined by the Constitution and law, as well as local governments.

International civil and security presences are operating under auspices of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244. Previously this included only the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), but has since expanded to include the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX). In December 2008, EULEX was deployed throughout the territory of Kosovo, assuming responsibilities in the areas of police, customs and the judiciary.[58]

A Kosovo Police Force was established in 1999.

Continued international supervision

The Ahtisaari Plan envisaged two forms of international supervision of Kosovo after independence: the International Civilian Office (ICO), which would monitor the implementation of the Plan and would have a wide range of veto powers over legislative and executive actions, and the European Union Rule of Law Mission to Kosovo (EULEX) which would have the narrower mission of deploying police and civilian resources (including prosecutors) with the aim of developing the Kosovo police and judicial systems but also with its own powers of arrest and prosecution. The Kosovo Declaration of Independence and subsequent Constitution granted these bodies the powers assigned to them by the Ahtisaari Plan. Since the Plan was not voted on by the UN Security Council, the ICO's legal status within Kosovo was dependent on the de facto situation and Kosovo legislation; it was supervised by an International Steering Group (ISG) composed of the main states which recognised Kosovo. It was never recognised by Serbia or other non-recognising states. EULEX was also initially opposed by Serbia, but its mandate and powers were accepted in late 2008 by Serbia and the UN Security Council as operating under the umbrella of the continuing UNMIK mandate, in a status-neutral way, but with its own operational independence. The ICO's existence terminated on 10 September 2012, after the ISG had determined that Kosovo had substantially fulfilled its obligations under the Ahtisaari Plan. EULEX continues its existence under both Kosovo and international law; in 2012 the Kosovo president formally requested a continuation of its mandate until 2014.

Constitution

The Republic of Kosovo is governed by legislative, executive and judicial institutions which derive from the Constitution of Kosovo, adopted in June 2008, although (as noted previously) North Kosovo is in practice largely controlled by institutions of the Republic of Serbia or parallel institutions funded by Serbia. The Constitution provides for a temporary international supervisory function exercised by the International Civilian Office (ICO), and, in the field of the rule of law, by EULEX. The International Steering Group has announced that the ICO's mandate has been successfully concluded and that the ICO ceased to exist on 10 September 2012 [59]

The Constitution[60] provides for a primarily parliamentary democracy, although the President has the power to return draft legislation to the Assembly for reconsideration, and has a role in foreign affairs and certain official appointments. It specifies that "the Republic of Kosovo is a secular state and is neutral in matters of religious beliefs". Like the Constitutional Framework before it, it guarantees a minimum of ten seats in the 120-member Assembly for Serbs, and ten for other minorities, and also guarantees Serbs and other minorities places in the Government.

A wide range of legislation affecting minority communities requires not only a majority in the Assembly for passage or amendment, but also the agreement of a majority of those Assembly members who are Serbs or from other minorities. Although Kosovo is not currently a member of the Council of Europe (and thus her citizens cannot appeal to the European Court of Human Rights) the Constitution enshrines the European Convention on Human Rights in Kosovo law, and gives it primacy over any domestic Kosovo laws. Kosovo's independent Constitutional Court has indeed overturned executive actions on the grounds that they infringe upon the Convention.

The Constitution provides extensive powers to the municipalities; boundaries of municipalities cannot be changed without their agreement. Three Serb-majority municipalities (North Mitrovica, Gračanica, and Štrpce) are directly given powers which other Kosovo municipalities do not have in the fields of university education and secondary health care; the constitutional right of Serb municipalities to associate and co-operate with each other means that, indirectly, they too have potential powers in these fields

Politics

The largest political parties in Kosovo are the centre-right Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), which has its origins in the 1990s non-violent resistance movement to Miloševic's rule and was led by Ibrahim Rugova until his death in 2006,[61] and two parties having their roots in the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA): the centre-left Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK) led by former KLA leader Hashim Thaçi and the centre-right Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK) led by former KLA commander Ramush Haradinaj.[61] In 2006 Swiss-Kosovar businessman Behgjet Pacolli, reputed to be the richest living Albanian, founded the New Kosovo Alliance (AKR), which came third in the 2007 elections and fourth in those of 2010.

In 2010, the Constitutional Court ruled that the first President of the Republic, Fatmir Sejdiu, was violating the Constitution by remaining leader of the LDK as well as being President. He chose to resign the Presidency rather than resign as leader of the party, but lost his leadership of the LDK anyway to Isa Mustafa, who campaigned for the leadership on a platform of leaving the Government coalition with the PDK. In the early elections which resulted from this political crisis, the PDK emerged as victors over the LDK, and formed a coalition with Behgjet Pacolli, the Serb Samostralna Liberalna Stranka, and other minority community parties.

The Assembly narrowly elected Behgjet Pacolli as President, but his election was subsequently declared invalid by the Constitutional Court on the grounds that it was unconstitutional for a Presidential election to have only one candidate. He was succeeded by Ahtifete Jahjaga.

Politics in Serb areas south of the River Ibar are dominated by the Independent Liberal Party (Samostalna Liberalna Stranka), led by Slobodan Petrovic; Serbs north of the river almost totally boycotted the Assembly elections of 2010

In February 2007 the Union of Serbian Districts and District Units of Kosovo and Metohija transformed into the Serbian Assembly of Kosovo and Metohija.[62] On 18 February 2008, day after Kosovo's declaration of independence, the assembly declared it "null and void".

Foreign relations

Nineteen countries maintain embassies in the Republic of Kosovo, and As of 11 February 2014, 108 countries recognise the Republic of Kosovo. Enver Hoxhaj is Foreign Minister for the Republic of Kosovo.[63]

Military

A 2,500-strong Kosovo Security Force (KSF) was trained by NATO instructors and became operational in September 2009.[64] The KSF did not replace the Kosovo Protection Corps (KPC) which was disbanded several months later. Agim Çeku is the current Minister of Security Forces of the Republic of Kosovo.[65]

Economy

Kosovo was the poorest part of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), and in the 1990s its economy suffered from the combined results of political upheaval, the Yugoslav wars, Serbian dismissal of Kosovo employees, and international sanctions on Serbia, of which it was then part.

After 1999, it had an economic boom as a result of post-war reconstruction and foreign assistance. In the period from 2003 to 2011, despite declining foreign assistance, growth of GDP averaged over 5% a year. This was despite the global financial crisis of 2009 and the subsequent eurozone crisis. Inflation was low.

Kosovo has a strongly negative balance of trade; in 2004, the deficit of the balance of goods and services was close to 70 percent of GDP, and was 39% of GDP in 2011. Remittances from the Kosovo diaspora accounted for an estimated 14 percent of GDP, little changed over the previous decade.[66][67] Most economic development since 1999 has taken place in the trade, retail and construction sectors. The private sector which has emerged since 1999 is mainly small-scale. The industrial sector remains weak. The economy, and its sources of growth, are therefore geared far more to demand than production, as shown by the current account, which was in 2011 in deficit by about 20% of GDP. Consequently Kosovo is highly dependent on remittances from the diaspora (the majority of these from Germany and Switzerland), FDI (of which a high proportion also comes from the diaspora), and other capital inflows.[66]

Government revenue is also dependent on demand rather than production; only 14% of revenue comes from direct taxes and the rest mainly from customs duties and taxes on consumption. In part this reflects low levels of production as shown in the current account; but in part it reflects very low direct taxation rates. In 2009 corporation tax was halved from 20% to 10%; the highest rate of income tax is also 10%.

However, Kosovo has very low levels of general government debt (only 5.8% of GDP),[66] although this would rise if Serbia recognised Kosovo and an agreement was reached on Kosovo's share of SFRY debt (which Serbia estimated in 2009 at $1.264 billion [68] and which it is currently servicing, though Kosovo is putting money into a separate account to take account, on a conservative basis, of potential liabilities). The Government also has liquid assets resulting from past fiscal surpluses (deposited in the Central Bank and invested abroad). Under applicable Kosovo law, there are also substantial assets from privatisation of socially owned enterprises (SOEs), also invested abroad by the Central Bank, which should mostly accrue to the Government when liquidation processes have been completed.[66]

The net foreign assets of the financial corporations and the Pension Fund amount to well over 50% of GDP. Moreover, the banking system in Kosovo seems very sound. For the banking system as a whole, the Tier One Capital Ratio as of January 2012 was 17.5%, double the ratio required in the EU; the proportion of non-performing loans was 5.9%, well below the regional average; and the credit to deposit ratio was only just above 80%. The assets of the banking system have increased from 5% of GDP in 2000 to 60% of GDP as of January 2012.[66] Since the housing stock in Kosovo is generally good by South-East European standards, this suggests that (if the legal system's ability to enforce claims on collateral and resolve property issues is trusted), credit to Kosovars could be safely expanded.

The United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) introduced an external trade office and customs administration on 3 September 1999, when it established border controls in Kosovo. All goods imported to Kosovo face a flat 10% duty.[69] These taxes are collected at all Customs Points at Kosovo's borders, including that between Kosovo and Serbia.[70] UNMIK and Kosovo institutions have signed free-trade agreements with Croatia,[71] Bosnia and Herzegovina,[72] Albania[73] and the Republic of Macedonia.[69]

The euro is the official currency of Kosovo.[74] Kosovo adopted the German mark in 1999 to replace the Serbian dinar,[75] and later replaced it with the euro, although the Serbian dinar is still used in some Serb-majority areas (mostly in the north). This means that Kosovo has no levers of monetary policy over its economy, and must rely on a conservative fiscal policy to provide the means to respond to external shocks.[66] Officially registered unemployment stood at 40% of the labour force in January 2012,[66][67] although some estimates have put it as high as 60%.[76] The IMF have pointed out, however, that informal employment is widespread, and the ratio of wages to per capita GDP is the second highest in South-East Europe; the true rate may therefore be lower.[66] Unemployment among the Roma minority may be as high as 90%.[77] The mean wage in 2009 was $2.98 per hour.

The dispute over Kosovo's international status, and the interpretation which some non-recognising states place on symbols which may or may not imply sovereignty, continues to impose economic costs on Kosovo. Examples include flight diversions because of a Serbian ban on flights to Kosovo over its territory; loss of revenues because of a lack of a regional dialling code (end-user fees on fixed lines accrue to Serbian Telecoms, while Kosovo has to pay Monaco and Slovenia for use of their regional codes for mobile phone connections; no IBAN code for bank transfers; and no regional Kosovo code for the Internet. Nevertheless, Information and communications technology in Kosovo has developed very rapidly and one survey has suggested that broadband internet penetration is comparable to the EU average.

A major deterrent to foreign manufacturing investment in Kosovo was removed in 2011 when the European Council accepted a Convention allowing Kosovo to be accepted as part of its rules for diagonal cumulative origination, allowing the label of Kosovo origination to goods which have been processed there but originated in a country elsewhere in the Convention. Since 2002 the European Commission has compiled a yearly progress report on Kosovo, evaluating its political and economic situation. Kosovo became a member of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund on 29 June 2009.

Trade and investment

Free trade: Customs-free access to the EU market based on the EU Autonomous Trade Preference (ATP) Regime, Central European Free Trade Area–CEFTA[78]

Kosovo enjoys a free trade within Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA), agreed with UNMIK, enabling its producers to access the regional market with its 28 million consumers, free of any customs duties. According to the Business Registry data for 2007, there are 2,012 companies of foreign and mixed ownership that have already used the opportunity to invest in Kosovo.[citation needed]

The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA, a member of the World Bank Group) guarantees investments in Kosovo in the value of 20 million Euro.[citation needed] The US Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) also provides political risk insurance for foreign investors in Kosovo.[79]

Municipalities and cities

Until 2007, Kosovo was divided into 30 municipalities. It is currently divided into 38 according to Kosovo law, in which ten municipalities have Serb majorities (including around 90% of the Serb population in Kosovo). Since Serbia does not recognise the legal validity of legislation by the Kosovo Assembly after the Declaration of Independence, it cannot recognise the legal validity even of new Serb-majority municipalities. However, the effective exercise of local administration - whether by authorities recognising Kosovo's independence, as is the case for Serb-majority municipalities south of the River Ibar, or not recognising it, as is the case for municipalities north of the River Ibar - follows the current boundaries established by Kosovo law.

List of municipalities

The first name is Serbian, and the second one is Albanian. An asterisk denotes a municipality created or enlarged after the Declaration of Independence of 2008, whose legal validity is not recognised by Serbia

| Municipality (Albanian: komuna, Serbian: opština / општина) is the basic administrative division of Kosovo The first name is Serbian and the second one is Albanian | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 01. Dečani / Deçan | 11. Leposavić / Albanik | 21. Prizren | |

| 02. Dragaš / Dragash | 12. Lipljan / Lipjan | 22. Srbica / Skënderaj | |

| 03. Đakovica / Gjakova | 13. Mališevo / Malishevë | 23. Štrpce / Shtërpcë | |

| 04. Glogovac / Gllogovc | 14. Kosovska Mitrovica / Mitrovicë | 24. Štimlje / Shtime | |

| 05. Gnjilane / Gjilan | 15. Novo Brdo / Novobërdë | 25. Suva Reka / Suharekë | |

| 06. Istok / Burim | 16. Obilić / Obiliq | 26. Uroševac / Ferizaj | |

| 07. Kačanik / Kaçanik | 17. Orahovac / Rahovec | 27. Vitina / Viti | |

| 08. Kosovska Kamenica / Kamenicë | 18. Peć / Pejë | 28. Vučitrn / Vushtrri | |

| 09. Klina / Klinë | 19. Podujevo / Podujevë | 29. Zubin Potok | |

| 10. Kosovo Polje / Fushë Kosovë | 20. Priština / Prishtinë | 30. Zvečan / Zveçan | |

| Source: OSCE - UNMIK Regulation 2000/43: Albanian, Serbian PDF | |||

Cities and towns

| Largest cities or towns of Republic of Kosovo Estimation of Kosovo Population 2012 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Districts | Pop. | Rank | Name | Districts | Pop. | |||

Pristina Prizren |

1 | Pristina | Pristina | 201,804 | 11 | Drenas | Pristina | 59,160 |  Ferizaj  Peja |

| 2 | Prizren | Prizren | 179,869 | 12 | Lipjan | Pristina | 58,292 | ||

| 3 | Ferizaj | Ferizaj | 109,899 | 13 | Rahovec | Gjakova | 56,932 | ||

| 4 | Peja | Peja | 97,360 | 14 | Malisheva | Prizren | 55,470 | ||

| 5 | Gjakova | Gjakova | 95,363 | 15 | Skënderaj | Mitrovica | 51,255 | ||

| 6 | Gjilan | Gjilan | 90,863 | 16 | Vitia | Gjilan | 47,408 | ||

| 7 | Podujeva | Pristina | 88,877 | 17 | Deçan | Peja | 40,392 | ||

| 8 | Mitrovica | Mitrovica | 84,949 | 18 | Istog | Peja | 39,727 | ||

| 9 | Vushtrri | Mitrovica | 70,495 | 19 | Klina | Peja | 39,047 | ||

| 10 | Suhareka | Prizren | 60,549 | 20 | Kamenica | Gjilan | 35,981 | ||

Rule of law

Following the Kosovo War, due to the many weapons in the hands of civilians, law enforcement inefficiencies, and widespread devastation, both revenge killings and ethnic violence surged tremendously. The number of reported murders rose 80% from 136 in 2000 to 245 in 2001. The number of reported arsons rose 140% from 218 to 523 over the same period. UNMIK pointed out that the rise in reported incidents might simply correspond to an increased confidence in the police force (i.e., more reports) rather than more actual crime.[80] According to the UNODC, by 2008, murder rates in Kosovo had dropped by 75% in five years.[81][82]

Although the number of noted serious crimes increased between 1999 and 2000, since then it has been "starting to resemble the same patterns of other European cities".[80][83] According to Amnesty International, the aftermath of the war resulted in an increase in the trafficking of women for sexual exploitation.[84][85][86] According to the IOM data, in 2000–2004, Kosovo was consistently ranked fourth or fifth among the countries of Southeastern Europe by number of human trafficking victims, after Albania, Moldova, Romania and sometimes Bulgaria.[87][88]

Residual landmines and other unexploded ordnance remain in Kosovo, although all roads and tracks have been cleared. Caution when travelling in remote areas is advisable.[89]

Kosovo is extremely vulnerable to organised crime and thus to money laundering. In 2000, international agencies estimated that Kosovo was supplying up to 40% of the heroin sold in Europe and North America.[90] Due to the 1997 unrest in Albania and the Kosovo War in 1998–1999 ethnic Albanian traffickers enjoyed a competitive advantage, which has been eroding as the region stabilises.[91] However, according to a 2008 report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, overall, ethnic Albanians, not only from Kosovo, supply 10 to 20% of the heroin in Western Europe, and the traffic has been declining.[92]

In 2010, a report by Swiss MP Dick Marty claimed to have evidence that a criminal network tied to the Kosovo Liberation Army and the Prime Minister, Hashim Thaci, executed prisoners and harvested their kidneys for organ transplantation. The Kosovo government rejected the allegation.[93] On 25 January 2011, the Council of Europe endorsed the report and called for a full and serious investigation into its contents.[94][95]

See also

- Albanians in Kosovo

- Albanian nationalism and independence

- Assembly of Kosovo

- Balkanisation

- Demographic history of Kosovo

- Disintegration of Yugoslavia

- European Alliance

- Government of Kosovo

- North Kosovo

- Serbian nationalism

- Albanian nationalism

- Serbs in Kosovo

References

Notes

- ↑ "Assembly approves Kosovo anthem", b92.net, 11 June 2008. Link accessed 11/06/08.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Kosovo". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ↑ "Distribution of family income – Gini index". The World Factbook. CIA. Archived from the original on 2010-07-23. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ↑ "Kosovo Human Development Report 2012"

- ↑ "Kosovo - definition of Kosovo by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ↑ "Kosovo seeks firm borders with Montenegro, Serbia". SETimes. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel, Kosovo: A Short History, pp. 354-356

- ↑ "Will the EBRD do the right thing for Kosovo, its newest member?". neurope.eu. 10 February 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ SANU (1986): Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts Memorandum. GIP Kultura. Belgrade.

- ↑ The Economist, 5 June 1999, U.S. Edition, 1041 words, "What's next for Slobodan Milošević?"

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Rogel, Carole. Kosovo: Where It All Began. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, Vol. 17, No. 1 (September 2003): 167–82.

- ↑ Clark, Howard. Civil Resistance in Kosovo. London: Pluto Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7453-1569-0.

- ↑ Noel Malcolm, A Short History of Kosovo pp. 346-7.

- ↑ Babuna, Aydın. Albanian national identity and Islam in the post-Communist era. Perceptions 8(3), September–November 2003: 43–69.

- ↑ Rama, Shinasi A. [http://www.alb-net.com/amcc/cgi-bin/viewnews.cgi?newsid985323600,53297, The Serb-Albanian War, and the International Community’s Miscalculations]. The International Journal of Albanian Studies, 1 (1998), pp. 15–19.

- ↑ "Operation Allied Force". NATO.

- ↑ Larry Minear, Ted van Baarda, Marc Sommers (2000). "NATO and Humanitarian Action in the Kosovo Crisis" (PDF). Brown University.

- ↑ "World: Europe UN gives figure for Kosovo dead". BBC News. 10 November 1999. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ↑ KiM Info-Service (7 June 2000). "3,000 missing in Kosovo". BBC News. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ↑ http://www.icty.org/sid/10095

- ↑ "ICTY.org" (PDF). Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "ICTY.org" (PDF). Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "ICTY.org" (PDF). Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "ICTY/org" (PDF). Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ http://www.tuzilastvorz.org.rs/html_trz/predmeti_eng.htm

- ↑ Another Albanian was indicted together with them, but the charges against him were promptly withdrawn after his arrest, as he turned out not to be the person referred to in the indictment.

- ↑ "ICTY.org" (PDF). Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "ICTY.org" (PDF). Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "Second Amended Indictment – Limaj et al". Icty.org. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ "Kosovo ex-PM Ramush Haradinaj cleared of war crimes". BBC News. 29 November 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ "Resolution 1244 (1999)". BBC News. 17 June 1999. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ↑ European Stability Initiative (ESI): The Lausanne Principle: Multiethnicity, Territory and the Future of Kosovo's Serbs (.pdf) , 7 June 2004.

- ↑ Coordinating Centre of Serbia for Kosovo-Metohija: Principles of the program for return of internally displaced persons from Kosovo and Metohija.

- ↑ "UN frustrated by Kosovo deadlock ", BBC News, 9 October 2006.

- ↑ Southeast European Times (29 June 2007). "Russia reportedly rejects fourth draft resolution on Kosovo status". Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ↑ Southeast European Times (10 July 2007). "UN Security Council remains divided on Kosovo". Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ↑ James Dancer (30 March 2007). "A long reconciliation process is required". Financial Times.

- ↑ Simon Tisdall (13 November 2007). "Bosnian nightmare returns to haunt EU". The Guardian (UK).

- ↑ "Europe , Q&A: Kosovo's future". BBC News. 11 July 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ "[http://www.osce.org/kosovo/13208.html: OSCE Mission in Kosovo – Elections] ", Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

- ↑ "[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/1846264.stm: Power-sharing deal reached in Kosovo] ", BBC News, 21 February 2002

- ↑ "Publicinternationallaw.org" (PDF). Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7179850.stm: Kosovo gets pro-independence PM] ", BBC News, 9 January 2008

- ↑ EuroNews: Ex-guerilla chief claims victory in Kosovo election. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- ↑ "Kosovo MPs proclaim independence", BBC News Online, 17 February 2008

- ↑ Hsu, Jenny W (20 February 2008). "Taiwan officially recognizes Kosovo". The Taipei Times. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ↑ "Recognition for new Kosovo grows", BBC News Online, 18 February 2008

- ↑ "Republic of Kosovo – IMF Staff Visit, Concluding Statement". Imf.org. 24 June 2009. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ "World Bank Cauntries".

- ↑ Accordance with international law of the unilateral declaration of independence in respect of Kosovo - Advisory opinion of 22 July 2010

- ↑ "Recognition Information and Statistics – Who Recognized Kosova? The Kosovar people thank you – Who Recognized Kosovo and Who Recognizes Kosovo". Kosovothanksyou.com. 1 November 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ↑ BBC News. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ↑ BBC News, Serbia's neighbours accept Kosovo . Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- ↑ "Kosovo Serbs convene parliament; Pristina, international authorities object (SETimes.com)". SETimes.com. 30 June 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/index.php?p1=3&p2=4&code=kos&case=141&k=21

- ↑ Serbia and Kosovo reach EU-brokered landmark accord, BBC News

- ↑ Belgrade, Pristina initial draft agreement (Serbian government website)

- ↑ Kosovo Under UNSCR 1244/99 2009 Progress Report, European Commission, 14 October 2009, p. 6

- ↑ http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/48043687/ns/world_news-europe/t/west-end-kosovo-independence-oversight-september

- ↑ Republic of Kosovo constitution, Republic of Kosovo constitution,

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "[http://www.europeanforum.net/country.php/kosovo_update#4: Kosovo Update: Main Political Parties] ", European Forum, 18 March 2008

- ↑ "Reuters AlertNet – Kosovo Serbs convene parliament, rejecting new state". Alertnet.org. 28 June 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ "Kosovo Foreign Ministry 'Soon'". BalkanInsight.com. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ "FSK nis zyrtarisht punën" (in Albanian). Pristina, Kosovo: Gazeta Express. 18 September 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ↑ "Composition of new cabinet government of the Republic of Kosovo, led by Prime Minister Hashim Thaci" kryeministri-ks.com 22 February 2011 Link retrieved 23 February 2011

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 66.4 66.5 66.6 66.7 IMF Country Report No 12/100 http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2012/cr12100.pdf "Unemployment, around 40% of the population, is a significant problem that encourages outward migration and black market activity."

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/enlargement_papers/2005/elp26en.pdf

- ↑ "Serbia should stop servicing Kosovo debt: EconMin , International". Reuters. 26 February 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Doing Business in Kosovo - U.S. Commercial Service Kosovo (UN Administered)

- ↑ http://www.seerecon.org/kosovo/documents/wb_econ_report/wb-kosovo-econreport-2-2.pdf

- ↑ Croatia, Kosovo sign Interim Free Trade Agreement, B92, 2 October 2006

- ↑ "UNMIK and Bosnia and Herzegovina Initial Free Trade Agreement". UNMIK Press Release, 17 February 2006.

- ↑ Oda Eknomike e Kosovës/Kosova Chambre of Commerce - Vision.To CMS V1.7 Powered by WWW.VISION.TO

- ↑ Invest in Kosovo – EU Pillar top priorities: privatisation process and focus on priority economic reforms

- ↑ BBC News, Kosovo adopts Deutschmark

- ↑ ECIKS - News and analysis about Kosovo Economy in English

- ↑ Roma forced back to dire poverty, deprivation 28 October 2010.

- ↑ PAK. "Economic Description:free trade".

- ↑ ECIKS. "Investments".

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 "UNMIK statistics". Unmikonline.org. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ Retrieved from Balkaninsight.com

- ↑ Crime and its impact on the Balkans and affected countries, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime report, March 2008. P. 39.

- ↑ Kosovo Crime Wave, 17 January 2001

- ↑ Kosovo UN troops 'fuel sex trade', BBC.

- ↑ Kosovo: Trafficked women and girls have human rights at the Wayback Machine (archived December 13, 2007), Amnesty International.

- ↑ Nato force 'feeds Kosovo sex trade', Guardian Unlimited.

- ↑ Second Annual Report on Victims of Trafficking in South-Eastern Europe. Geneva:International Organization for Migration, 2005. P. 31, 247–295.

- ↑ Crime and its impact on the Balkans and affected countries, UNODC report, March 2008. P. 79.

- ↑ "Kosovo travel advice". Fco-stage.fco.gov.uk. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ O'Kane, Maggie (13 March 2000). "Kosovo drug mafia supply heroin to Europe , World news". The Guardian (UK). Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ Crime and its impact on the Balkans and affected countries, UNODC report, March 2008. P. 14.

- ↑ Crime and its impact on the Balkans and affected countries, UNODC report, March 2008. P. 14, 74.

- ↑ BBC (15 December 2010). "Kosovo rejects Hashim Thaci organ-trafficking claims". BBC News.

- ↑ 'Kosovo physicians accused of illegal organs removal racket' The Guardian, 14 December 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ↑ "Council Adopts Kosovo Organ Trafficking Resolution". Balkan Insight. 25 January 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

Sources

- Lellio, Anna Di (June 2006), The case for Kosova: passage to independence, Anthem Press, ISBN 978-1-84331-229-1

- Elsie, Robert (2004), Historical Dictionary of Kosova, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0-8108-5309-4

- Malcolm, Noel (1998), Kosovo: A Short History, Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-66612-7

External links

| Find more about Republic of Kosovo at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| |

Definitions and translations from Wiktionary |

| |

Media from Commons |

| |

Quotations from Wikiquote |

| |

Source texts from Wikisource |

| |

Textbooks from Wikibooks |

| |

Learning resources from Wikiversity |

- United Nations Interim Administration in Kosovo

- European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo

- Government of the Republic of Kosovo

- Serbian Ministry for Kosovo and Metohija

Wikimedia Atlas of Kosovo

Wikimedia Atlas of Kosovo- Kosovo entry at The World Factbook

- Republic of Kosovo on the Open Directory Project

Republic of Kosovo travel guide from Wikivoyage

Republic of Kosovo travel guide from Wikivoyage

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)