Religion in Germany

Christianity is the largest religion in Germany with roughly 50 million adherents or 62% of the total population,[4][5] The second largest religion is Islam with 4 million adherents, making up 5% of the country's total population[4] followed by Buddhism and Judaism. During the last few decades, the two largest churches in Germany, namely the Protestant Evangelical Church in Germany and the Roman Catholic Church, have lost significant number of adherents. Both accounted for about 30% of the population in 2011.[6][5] More than 30% of the population is not affiliated with any church or other religious body.[4][5]

Since the reunification of Germany the number of non-religious people has grown, especially because of the former East Germany, which was an atheist and communist puppet state. Various churches were put under the pressure by the communist government for roughly 40 years, resulting in people's abandonment of religion.[7] Due to losses of both the Protestant churches and the Catholic Church in Hamburg, this state has also joined the group of states with a non-religious majority.[8]

History

Roman Catholicism was the sole established religion in the Holy Roman Empire until the advent of the Protestant Reformation changed this drastically. Beginning In 1517, Martin Luther challenged the Catholic Church to make reforms, as he saw it as a corruption of Christian faith. Though he did not intend for the Church to break apart, the division between those who accepted the need for reform and those who did not led to the establishment of new churches. Luther's actions he altered the course of European and world history and established Protestantism.[9] The Holy Roman Empire became home to numerous religious affiliations; for the most part, the states of northern and central Germany tended to adopt Protestantism (chiefly Lutheranism, but also Calvinism), while the states of southern Germany and the Rhineland largely remained Catholic. Each prince was free to choose the religion of his state under the principle of Cuius regio, eius religio .

The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history. The war was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most of the countries of Europe. The war was fought largely as a religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics in the Holy Roman Empire.[10]

Religious freedom

The national constitutions of 1919 and 1949 guarantee freedom of faith and religion; earlier, these freedoms were mentioned only in state constitutions. The modern constitution of 1949 also states that no one may be discriminated against due to their faith or religious opinions. A state church does not exist in Germany.[11]

Religious communities that are of considerable size and stability and are loyal to the constitution can be recognised as "Körperschaften öffentlichen Rechtes" (statutory corporation). This gives them certain privileges, for example being able to give religious instruction in state schools (as enshrined in the German constitution, though some states are exempt from this) and having membership fees collected (for a fee) by the German revenue department as Church tax. It is a surcharge amounting to between 8 or 9% of the income tax. The status mainly applies to the Roman Catholic Church, the mainline Protestant EKD, and Jewish communities. There have been numerous discussions of allowing other religious groups like Jehovah's Witnesses and Muslims into this system as well. The Muslim efforts were hampered by the Muslims' own disorganised state in Germany, with many small rivalling organisations and no central leadership, which does not fit well into a legal frame that was originally created with well-organized, large Christian churches in mind.

Statistics

According to organizational reportings based on projections in 2008 about 34.1% Germans have no registered religious denomination.

Christianity is the largest religion in Germany, with around 52 million adherents (62.8%) in 2008[13] of which 24.5 million are Protestants (29.9%) belonging to the EKD and 24.9 million are Catholics (30.0%) in 2008, the remainder belong to small denominations (each (considerably ) less than 0.5% of the German population).[14] The second largest religion is Islam with an estimated 3.8 to 4.3 million adherents (4.6 to 5.2%)[15] followed by Buddhism and Judaism, both with around 200,000 adherents (0.3%). Hinduism has some 90,000 adherents (0.1%) and Sikhism 75,000 (0.1%). All other religious communities in Germany have fewer than 50,000 (<0.1%) adherents.

Protestantism is concentrated in the north and east and Roman Catholicism is concentrated in the south and west. The former Pope, Benedict XVI, was born in Bavaria. Non-religious people, including atheists and agnostics might make as many as 55%, and are especially numerous in the former East Germany and major metropolitan areas.[16]

Of the roughly 4 million Muslims, most are Sunnis and Alevites from Turkey, but there are a small number of Shi'ites and other denominations.[15][17] 1.6% of the country's overall population declare themselves Orthodox Christians, Serbs and Greeks being the most numerous.[13] Germany has Europe's third-largest Jewish population (after France and the United Kingdom).[18] In 2004, twice as many Jews from former Soviet republics settled in Germany as in Israel, bringing the total Jewish population to more than 200,000, compared to 30,000 prior to German reunification. Large cities with significant Jewish populations include Berlin, Frankfurt, and Munich.[19] Around 250,000 active Buddhists live in Germany; 50% of them are Asian immigrants.[20]

According to the Eurobarometer Poll 2010, 45% of German citizens agreed with the statement "I believe there is a God", whereas 25% agreed with "I believe there is some sort of spirit or life force" and 27% said "I do not believe there is any sort of spirit, god, or life force".[21] According to a new 2012 poll released by WIN-Gallup International, 51% of the German citizens said that they are religious, 33% said not religious, 15% said atheist, and 1% gave no answer.

2011 census

According to the 2011 census:

- Roman Catholic Church: 24,740,380 or 30.8% of the German population;

- Evangelical Church: 24,328,100 or 30.3% of the German population;

- Other, atheist or not specified: 31,151,210 or 38.8% of the German population.[22]

-

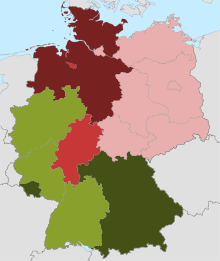

Evangelical population according to 2011 census

-

Catholic population according to 2011 census

-

Non-religious population according to 2011 census (incl. other religions and not specified)

-

Pre-dominant religious group according to census 2011, catholics are dominant (I.e. The majority in the south and west, the Non-religious (incl. other religions and not specified)dominate in the east and the large cities, protestants in the remainder of Germany)

Christianity

Christianity is the largest religion in Germany,[4] with the Protestant Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) comprising 29.9% [23] as of 31 December 2008 (down 0.3% compared to the 30.2%[24] in the year before) of the population and Roman Catholicism comprising 30.7% as of Dec. 2008[25] (also down 0.3% compared to the year before).[26] Consequently a majority of the German people belong to a Christian community, although many of them take no active part in church life. About 1.7% of the population is Orthodox Christian.[4]

Independent and congregational churches exist in all larger towns and many smaller ones, but most such churches are small. One of these is the confessional Lutheran Church called Independent Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Germany.

- Christians 52 million (approximately 62%)[4]

Protestantism

- Total: 26 million

- Evangelical Church in Germany 23.9 million (29.2%) as of 31 December 2010 [4]

- New Apostolic Church 400,000[27]

- Aussiedler-Baptisten 300,000-380,000[27]

- Free Evangelical / Charismatic 232,000[28]

- Baptists (mostly Bund Evangelisch-Freikirchlicher Gemeinden in Deutschland KdöR) 86,500[27]

- Methodists 65,638[28]

- Christliche Versammlungen / Freier Brüderkreis / Plymouth Brethren 45,000[29]

- Bund Freikirchlicher Pfingstgemeinden (Pentecostal) 40,000

- Evangelical Methodist Church (Evangelisch-methodistische Kirche), part of the worldwide United Methodist Church 38,000

- Independent Evangelical-Lutheran Church 36,000[30]

- Mennonites 39,414[29]

- Seventh-day Adventist Church 36,000

- Apostelamt Jesu Christi 20,000[23]

- Bund Evangelisch-reformierter Kirchen Deutschlands (Reformed) 13,000

- Christengemeinden Elim (Pentecostal) 10,000

- Danish Church in Southern Schleswig 6,500

- Apostolische Gemeinschaft 6,000

- Gemeinde der Christen - Ecclesia 4,000[30]

- Johannische Church (Johannische Kirche) 3,500

- Church of the Nazarene 1,984[28]

- Gemeinde Christi (Churches of Christ) 1,400

Catholicism

- Total: 24.5 million

- Roman Rite Catholics 24.47 million (29.9%)[4]

- Old Catholic Church 15,000[4]

- Maronite Rite Catholics 6,000[4]

Orthodoxy

- Total: 1.5 million (2%)

- Orthodox Church of Constantinople/Greek Orthodox Church 450,000 [27]

- Romanian Orthodox Church 300,000[27]

- Serbian Orthodox Church 250,000[4][27]

- Russian Orthodox Church 150,000[4]

- Bulgarian Orthodox Church 66,000[4]

- Syriac Orthodox Church 55,000[4]

- Armenian Apostolic Church 35,000[28]

- Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church 13,000[28]

- Assyrian Church 10,000[28]

- Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church 3,600[30]

- Coptic Orthodox Church 3,000[28]

- Ukrainian Orthodox Church - Kyiv Patriarchate 1,000

Others

- Total: .2 million

- Jehovah's Witnesses 166,000[27]

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 38,668[31]

- Christian Community 10,000

Secularism

Before World War II, about two-thirds of the German population was Protestant and one-third was Roman Catholic. In the north and northeast of Germany especially, Protestants dominated.[32] In the former West Germany between 1945 and 1990, which contained nearly all of Germany's historically Catholic areas, Catholics have had a small majority since the 1980s. Due to a generation behind the Iron Curtain Protestant areas of the former states of Prussia were much more affected by secularism than predominantly Catholic areas. The predominantly secularised states, such as Hamburg or the East German states, used to be Lutheran or United Protestant strongholds.

There is a non-religious majority in Hamburg, Berlin, Brandenburg, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. In the eastern state of Saxony-Anhalt only 19.7 percent belong to the two big denominations of the country.[33] This is the state where Martin Luther was born.

In eastern Germany both religious observance and affiliation are much lower than in the rest of the country after forty years of Communist rule. The government of the German Democratic Republic encouraged an atheist worldview through institutions such as Jugendweihen (youth consecrations), secular coming-of-age ceremonies akin to Christian confirmation which all young people were strongly encouraged to attend (and disadvantaged socially if they did not). The average church attendance is now one of the lowest in the world, with only 5% attending at least once per week, compared to 14% in the rest of the country according to a recent study.[citation needed] The number of christenings, religious weddings and funerals is also lower than in the West.

According to a survey among German youths (aged between 12 and 24) in the year 2006, 30% of German youths believe in a personal god, 19% believe in some kind of supernatural power, 23% share agnostic views and 28% are atheists.[34]

No religion

- No religion specified (25-33%)[27]

Paganism

Neopagan religions have been public in Germany at least since the 19th century. Nowadays Germanic Heathenism (Germanisches Heidentum, or Deutschglaube for its peculiar German forms) has many organisations in the country, including the Germanische Glaubens-Gemeinschaft (Communion of Germanic Faith), the Heidnische Gemeinschaft (Heathen Communion), the Verein für germanisches Heidentum (Association for Germanic Heathenry) the Nornirs Ætt, the Eldaring, the Artgemeinschaft, the Armanen-Orden, and Thuringian Firne Sitte.

Other Pagan religions include the Celto-Germanic Matronenkult grassroots worship practiced in Rhineland, Celtoi (a Celtic religious association) and Wiccan groups. 1% of the population of North Rhine-Westphalia adheres to new religions or esoteric groups as of 2006.

Islam

Islam is the largest non-Christian religion in the country. The majority of Muslims in Germany are of Turkish origin (63.2%), followed by those from Pakistan, countries of the former Yugoslavia, Arab countries, Iran and Afghanistan. As of 2006, according to the U.S. Department of State, approximately 3.2 million Muslims live in Germany. This figure includes the different denominations of Islam, such as Sunni, Shia, Ahmadiyya and Alevites. Studies have also shown that several thousand Germans have converted to Islam.[35]

Muslims first came to Germany as part of the diplomatic, military and economic relations between Germany and the Ottoman Empire in the 18th century.[36] In World War I about 15,000 Muslim prisoners of war were interned in Berlin. The first mosque was established in Berlin in 1915 for these prisoners, though it was closed in 1930. After the West German Government invited foreign workers in 1961, the Muslim population continuously rose.

- Total: 3.6 million (4%), of which 1 million (1.1%) has German citizenship.

- Sunni 2.5 M[27]

- Alevite 441,000 [37]

- Shi'a 225,000[27]

- Ahmadiyya 50,000[38]

- Ismaili 12,000

- Sufi 10,000

Judaism

Today Germany, especially its capital Berlin, has the fastest growing Jewish community worldwide. About ninety thousand Jews from the former Eastern Bloc, mostly from ex-Soviet Union countries, settled in Germany since the fall of the Berlin wall. This is mainly due to a German government policy which effectively grants an immigration ticket to anyone from the CIS and the Baltic states with Jewish heritage, and the fact that today's Germans are seen as significantly more accepting of Jews than many people in the ex-Soviet realm. Some of the about 60,000 long-time resident German Jews have expressed some mixed feelings about this immigration that they perceive as making them a minority not only in their own country but also in their own community. Prior to Nazism, about 600,000 Jews lived in Germany, with communities going back to the 4th century.[39]

- Total: 200,000 (0.25%)[27]

- Union of Progressive Jews in Germany: 3,000 members

- Central Council of Jews in Germany: Most Jewish communities

Buddhism, Hinduism, other religions

- Buddhists 245,000 (0.30%)

- Hindu 97,500[27]

- Sikh 50,000 (see Sikhism in Germany)

- Bahá'í Faith 5000-6000,[40] with one of only seven Houses of Worship in the world, see Bahá'í Faith in Germany

- Yazidi

Cults, Sects, Religious movements

The German government as well as the churches are actively involved in disseminating information and warnings about sects and cults (in colloquial language the German word Sekte is used in both senses[citation needed]) and new religious movements. In public opinion, minor religious groups are often referred to as Sekten, which can both refer to destructive cults but also to all religious movements which are not Christian or different from the Roman Catholicism and the mainstream Protestantism. However, major world religions like mainstream Orthodox Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism and Islam are not referred to as Sekten.[citation needed]

- Information by the Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland (Evangelic Church in Germany) and Roman Catholic Church

When classifying religious groups, the Roman Catholic Church and the mainline Protestant Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) use a three-level hierarchy of "churches", "free churches" and Sekten:

- Kirchen (churches) is the term generally applied to the Roman Catholic Church, the Evangelical Church in Germany's member churches (Landeskirchen), and the Orthodox Churches. The churches are not only granted the status of a non-profit organisation, but they have additional rights as statutory corporations (German: Körperschaft des öffentlichen Rechts), which means they have the right to employ civil servants (Beamter), do official duties or issue official documents.

- Freikirchen (free churches) is the term generally applied to Protestant organisations outside of the EKD, e.g. Baptists, Methodists, independent Lutherans, Pentecostals, Seventh-day Adventists. However, the Old Catholics can be referred to as a free church as well[41] The free churches are not only granted the tax-free status of a non-profit organisation, but many of them have additional rights as statutory corporations.

- Sekten is the term for religious groups which do not see themselves as part of a major religion (but maybe as the only real believers of a major religion).[42][42] Although these religious groups have full religious freedom and protection against discrimination of their members, their organisations in most cases are not granted the tax-free status of a non-profit organisation[citation needed].

Every Protestant Landeskirche (church whose canonical jurisdiction extends over one or several states, or Länder) and Catholic episcopacy has a Sektenbeauftragter (Sekten delegate) from whom information about religious movements may be obtained.

- Information by the government

The German government also provides information about cults, sects, and new religious movements. In 1997, the parliament set up a commission for Sogenannte Sekten und Psychogruppen (literally "so-called sects and psychic groups") which delivered an extensive report on the situation in Germany regarding NRMs in 1998.[43] In 2002, the Federal Constitutional Court upheld the governmental right to provide critical information on religious organizations being referred to as Sekte, but stated that "defamatory, discriminating, or falsifying accounts" were illegal.[44]

See also

- Religion by country

- Evangelical Church in Germany

- History of Germany

- Lutheranism

- Martin Luther

- Max Weber

- United and uniting churches

- List of churches in Hamburg

- Irreligion in Germany

References

- ↑ Bevölkerung und Kirchenzugehörigkeit nach Bundesländern Table 1.1 shows 63.4 % of the German population to be Christians of which 2.2% outside the Evangelische Landeskirchen (EKD) and the Roman Catholic Church. Table 1.3 shows overview by German state of membership of the Evangelische Landeskirchen (EKD)and the Roman Catholic Church

- ↑ 80% of population in Sachsen-Anhalt is without religion

- ↑ religion by Bundesland showing non religious being the majority in Eastern Germany

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Religionen in Deutschland - Mitglieder und Anhänger

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Zensus 2011 - Ergebnisse, page 6

- ↑ Bevölkerung und Katholiken, 1965–2008

- ↑ "Germany". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ↑ EKD Kirchenmitgliederzahlen (church members as of) 31.12.2007 document in German issued in November 2008 - shows also the number of Roman Catholics and Protestants by Bundesland

- ↑ Plass, Ewald M., What Luther Says: An Anthology, St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1959, 2:964.

- ↑ Schiller, Frederick, History of the Thirty Years' War, p.1, Harper Publishing

- ↑ Basic Law Art. 140

- ↑ Views on globalisation and faith. Ipsos MORI, 5th July 2011.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 (German) "EKD-Statistik: Christen in Deutschland 2007". Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- ↑ Konfessionen in Deutschland(German), fowid. Retrieved 2010, 9 September 2009.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Chapter 2: Wie viele Muslime leben in Deutschland?" [How many Muslims live in Germany?] (PDF). Muslimisches Leben in Deutschland [Muslim Life in Germany] (in German). Nuremberg: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (German: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge), an agency of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (Germany). June 2009. p. 80. ISBN 978-3-9812115-1-1. Retrieved 2010-09-09. "Demnach leben in Deutschland zwischen 3,8 und4,3 Millionen Muslime [. . .] beträgt der Anteil der Muslime an der Gesamtbevölkerungzwischen 4,6 und 5,2 Prozent. Rund 45 Prozent der in Deutschland lebenden Muslime sind deutsche Staatsangehörige,rund 55 Prozent haben eine ausländische Staatsangehörigkeit."

- ↑ (German) Religionen in Deutschland: Mitgliederzahlen Religionswissenschaftlicher Medien- und Informationsdienst; 31 October 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ↑ "Chapter 2: Wie viele Muslime leben in Deutschland?" [How many Muslims live in Germany?] (PDF). Muslimisches Leben in Deutschland [Muslim Life in Germany] (in German). Nuremberg: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (German: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge), an agency of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (Germany). June 2009. p. 97. ISBN 978-3-9812115-1-1. Retrieved 2010-09-09. "Der Anteil der Sunniten unter den in den Haushalten lebenden Muslimen beträgt 74 Prozent"

- ↑ Blake, Mariah. In Nazi cradle, Germany marks Jewish renaissance Christian Science Monitor. 10 November 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-30.

- ↑ The Jewish Community of Germany European Jewish Congress. Retrieved 2006-11-30.

- ↑ (German) Die Zeit 12/07, page 13

- ↑ Eurobarometer Biotechnology report 2010 p.381

- ↑ Zensus 2011 - Ergebnisse, page 6

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Adherents.com: By Location

- ↑ EKD church members as of 31 Dec. 2007

- ↑ German Catholic Church 2008 statistics

- ↑ German Catholic Church 2007 statistics

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 27.7 27.8 27.9 27.10 27.11 Germany

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 Adherents.com: By Location

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Adherents.com: By Location

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Adherents.com: By Location

- ↑ LDS Newsroom (Germany)

- ↑ Ericksen & Heschel, Betrayal: German churches and the Holocaust, p.10, Fortress Press.

- ↑ http://www.ekd.de/download/kimi_2004.pdf

- ↑ Thomas Gensicke: Jugend und Religiosität. In: Deutsche Shell Jugend 2006. Die 15. Shell Jugendstudie. Frankfurt a.M. 2006.

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/the-islamification-of-britain-record-numbers-embrace-muslim-faith-2175178.html The Islamification of Britain: record numbers embrace Muslim faith

- ↑ State Policies Towards Muslim Minorities. Sweden, Great Britain and Germany, "Muslims in German History until 1945", Jochen Blaschke

- ↑ http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2007/90177.htm

- ↑ http://www.integration-in-deutschland.de/nn_285170/SubSites/Integration/EN/02__Zuwanderer/ThemenUndPerspektiven/Islam/Deutschland/deutschland-node.html?__nnn=true

- ↑ "Germany: Virtual Jewish History Tour". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Verschiedene Gemeinschaften / neuere religiöse Bewegungen". Religionen in Deutschland: Mitgliederzahlen (Membership of religions in Germany). REMID - the "Religious Studies Media and Information Service" in Germany. 2007-8. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ Altkatholiken Freikirche

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Definition "Sekte"

- ↑ Final report of the commission of the Bundestag on the investigation into so-called sects and psycho groups

- ↑ Decision of the German Federal Constitutional Court: BVerfG, Urteil v. 26.06.2002, Az. 1 BvR 670/91

External links

- Eurel: sociological and legal data on religions in Europe

- Germany - Catholic Encyclopedia

- Germany - Sacred Destinations

- Statistic by REMID about Adherence to Religious Communities in Germany

- Germans Reconsider Religion

- Religion in Germany (Deutschland): Mitgliederzahlen

- History of Pentecostal Churches in Germany

- KOKID - Kommission der Orthodoxen Kirche in Deutschland (Commission of the Orthodox Church in Germany)

- Das elektronische Informationssystem über neue religiöse und ideologische Gemeinschaften, Psychogruppen und Esoterik in Deutschland

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||