Refractive index

In optics the refractive index or index of refraction n of a substance (optical medium) is a dimensionless number that describes how light, or any other radiation, propagates through that medium. It is defined as

,

,

where c is the speed of light in vacuum and v is the speed of light in the substance. For example, the refractive index of water is 1.33, meaning that light travels 1.33 times slower in water than it does in vacuum. (See typical values for different materials here.)

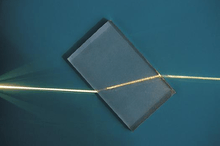

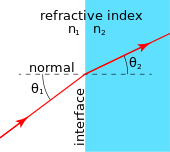

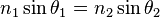

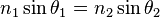

The refractive index determines how much light is bent, or refracted, when entering a material. This is the historically first use of refractive indices and is described by Snell's law of refraction,

,

where

,

where  and

and  are the angles of incidence and refraction, respectively, of a ray crossing the interface between two media with refractive indices

are the angles of incidence and refraction, respectively, of a ray crossing the interface between two media with refractive indices  and

and  . The refractive indices also determine the amount of light that is reflected when reaching the interface, as well as the critical angle for total internal reflection and Brewster's angle.[2]

. The refractive indices also determine the amount of light that is reflected when reaching the interface, as well as the critical angle for total internal reflection and Brewster's angle.[2]

The refractive index can be seen as the factor by which the speed and the wavelength of the radiation are reduced with respect to their vacuum values: the speed of light in a medium is  , and similarly the wavelength in that medium is

, and similarly the wavelength in that medium is  , where

, where  is the wavelength of that light in vacuum. This implies that vacuum has a refractive index of 1, and that the frequency (

is the wavelength of that light in vacuum. This implies that vacuum has a refractive index of 1, and that the frequency ( ) of the wave is not affected by the refractive index.

) of the wave is not affected by the refractive index.

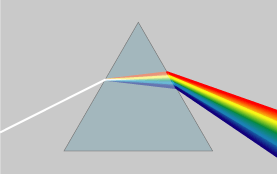

The refractive index varies with the wavelength of light. This is called dispersion and causes the splitting of white light into its constituent colors in prisms and rainbows, and chromatic aberration in lenses. Light propagation in absorbing materials can be described using a complex-valued refractive index.[3] The imaginary part then handles the attenuation, while the real part accounts for refraction.

The concept of refractive index is widely used within the full electromagnetic spectrum, from x-rays to radio waves. It can also be used with wave phenomena such as sound. In this case the speed of sound is used instead of that of light and a reference medium other than vacuum must be chosen.[4]

Definition

The refractive index n of an optical medium is defined as the ratio of the speed of light in vacuum, c = 299792458 m/s, and the phase velocity vphase of light in the medium,

.[2]

.[2]

The phase velocity is the speed at which the crests and the phase of the wave moves, which may be different from the group velocity, the speed at which the pulse of light, or the envelope of the wave, moves.

The definition above is sometimes referred to as the absolute index of refraction to distinguish it from definitions where the speed of light in other reference media than vacuum is used.[2] Historically air at a standardized pressure and temperature have been common as a reference medium.

History

.jpg)

Thomas Young was presumably the person who first used, and invented, the name "index of refraction", in 1807.[5] At the same time he changed this value of refractive power into a single number, instead of the traditional ratio of two numbers. The ratio had the disadvantage of different appearances. Newton, who called it the "proportion of the sines of incidence and refraction", wrote it as a ratio of two numbers, like "529 to 396" (or "nearly 4 to 3"; for water).[6] Hauksbee, who called it the "ratio of refraction", wrote it as a ratio with a fixed numerator, like "10000 to 7451.9" (for urine).[7] Hutton wrote it as a ratio with a fixed denominator, like 1.3358 to 1 (water).[8]

Young did not use a symbol for the index of refraction, in 1807. In the next years, others started using different symbols: n, m, and µ.[9] [10] [11] The symbol n gradually prevailed.

Typical values

| Material | n |

|---|---|

| Gases at 0 °C and 1 atm | |

| Air | 1.000293 |

| Helium | 1.000036 |

| Hydrogen | 1.000132 |

| Carbon dioxide | 1.00045 |

| Liquids at 20 °C | |

| Water | 1.333 |

| Ethanol | 1.36 |

| Olive oil | 1.47 |

| Solids | |

| Ice | 1.309 |

| Soda-lime glass | 1.46 |

| PMMA (Plexiglas) | 1.49 |

| Crown glass (typical) | 1.52 |

| Flint glass (typical) | 1.62 |

| Diamond | 2.42 |

For visible light most transparent media have refractive indices between 1 and 2. A few examples are given in the table to the right. These values are measured at the yellow doublet sodium D-line, with a wavelength of 589 nanometers, as is conventionally done. Gases at atmospheric pressure have refractive indices close to 1 because of their low density. Almost all solids and liquids have refractive indices above 1.3, with aerogel as the clear exception. Aerogel is a very low density solid that can be produced with refractive index in the range from 1.002 to 1.265.[12] Diamond lies at the other end of the range with a refractive index as high as 2.42. Most plastics have refractive indices in the range from 1.3 to 1.7, but some high-refractive-index polymers can have values as high as 1.76.[13]

For infrared light refractive indices can be considerably higher. Germanium is transparent in this region and has a refractive index of about 4, making it an important material for infrared optics.

Refractive index below 1

A widespread misconception is that since, according to the theory of relativity, nothing can travel faster than the speed of light in vacuum, the refractive index cannot be lower than 1. This is erroneous since the refractive index measures the phase velocity of light, which does not carry information. The phase velocity is the speed at which the crests of the wave move and can be faster than the speed of light in vacuum, and thereby give a refractive index below 1. This can occur close to resonance frequencies, for absorbing media, in plasmas, and for x-rays. In the x-ray regime the refractive indices are lower than but very close to 1 (exceptions close to some resonance frequencies).[14] As an example, water has a refractive index of 0.99999974 = 1 − 2.6×10−7 for x-ray radiation at a photon energy of 30 keV (0.04 nm wavelength).[14]

Negative refractive index

Recent research has also demonstrated the existence of materials with a negative refractive index, which can occur if permittivity and permeability have simultaneous negative values. This can be achieved with periodically constructed metamaterials. The resulting negative refraction (i.e., a reversal of Snell's law) offers the possibility of the superlens and other exotic phenomena.

Microscopic explanation

At the microscale, an electromagnetic wave's phase velocity is slowed in a material because the electric field creates a disturbance in the charges of each atom (primarily the electrons) proportional to the electric susceptibility of the medium. (Similarly, the magnetic field creates a disturbance proportional to the magnetic susceptibility.) As the electromagnetic fields oscillate in the wave, the charges in the material will be "shaken" back and forth at the same frequency.[15] The charges thus radiate their own electromagnetic wave that is at the same frequency, but usually with a phase delay, as the charges may move out of phase with the force driving them (see sinusoidally driven harmonic oscillator). The light wave traveling in the medium is the macroscopic superposition (sum) of all such contributions in the material: the original wave plus the waves radiated by all the moving charges. This wave is typically a wave with the same frequency but shorter wavelength than the original, leading to a slowing of the wave's phase velocity. Most of the radiation from oscillating material charges will modify the incoming wave, changing its velocity. However, some net energy will be radiated in other directions or even at other frequencies (see scattering).

Depending on the relative phase of the original driving wave and the waves radiated by the charge motion, there are several possibilities:

- If the electrons emit a light wave which is 90° out of phase with the light wave shaking them, it will cause the total light wave to travel more slowly. This is the normal refraction of transparent materials like glass or water, and corresponds to a refractive index which is real and greater than 1.[16]

- If the electrons emit a light wave which is 270° out of phase with the light wave shaking them, it will cause the total light wave to travel more quickly. This is called "anomalous refraction", and is observed close to absorption lines, with x-rays, and in some microwave systems. It corresponds to a refractive index less than 1. (Even though the phase velocity of light is greater than the speed of light in vacuum c, the signal velocity is not, as discussed above). If the response is sufficiently strong and out-of-phase, the result is negative refractive index discussed below.[16]

- If the electrons emit a light wave which is 180° out of phase with the light wave shaking them, it will destructively interfere with the original light to reduce the total light intensity. This is light absorption in opaque materials and corresponds to an imaginary refractive index.

- If the electrons emit a light wave which is in phase with the light wave shaking them, it will amplify the light wave. This is rare, but occurs in lasers due to stimulated emission. It corresponds to an imaginary index of refraction, with the opposite sign as absorption.

For most materials at visible-light frequencies, the phase is somewhere between 90° and 180°, corresponding to a combination of both refraction and absorption.

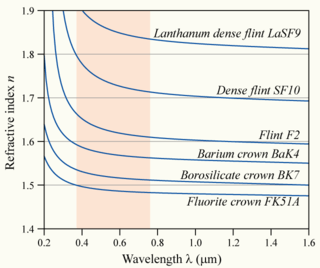

Dispersion

The refractive index of materials varies with the wavelength (and frequency) of light. This is called dispersion and causes prisms to divide white light into its constituent spectral colors, and explains how rainbows are formed. As the refractive index varies with wavelength, according to Snell's law, so will the refraction angle as light goes from one material to another. This makes different colors go in different directions. Dispersion also causes the focal length of lenses to be wavelength dependent. This is a type of chromatic aberration, which often needs to be corrected for in imaging systems.

In regions of the spectrum where the material does not absorb, the refractive index tends to decrease with increasing wavelength, and thus increase with frequency. This is called normal dispersion, in contrast to anomalous dispersion, where the refractive index increases with wavelength. For visible light normal dispersion means that the refractive index is higher for blue light than for red.

For optics in the visual range the amount of dispersion of a lens material is often quantified by the Abbe number  . For a more accurate description of the wavelength dependence of the refractive index the Sellmeier equation can be used. It is an empirical formula that works well in describing dispersion. Sellmeier coefficients are often quoted instead of the refractive index in tables.

. For a more accurate description of the wavelength dependence of the refractive index the Sellmeier equation can be used. It is an empirical formula that works well in describing dispersion. Sellmeier coefficients are often quoted instead of the refractive index in tables.

Because of dispersion, it is usually important to specify the vacuum wavelength at which a refractive index is measured. Typically, this is done at various well-defined spectral emission lines; for example, nD is the refractive index at the Fraunhofer "D" line, the centre of the yellow sodium double emission at 589.29 nm wavelength.

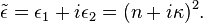

Complex index of refraction and absorption

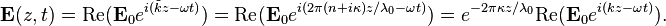

When light passes through a medium, some part of it will always be absorbed. This can be conveniently taken into account by defining a complex index of refraction,

Here, the real part of the refractive index  indicates the phase velocity, while the imaginary part

indicates the phase velocity, while the imaginary part  indicates the amount of absorption loss when the electromagnetic wave propagates through the material.

indicates the amount of absorption loss when the electromagnetic wave propagates through the material.

That  corresponds to absorption can be seen by inserting this refractive index into the expression for electric field of a plane electromagnetic wave traveling in the

corresponds to absorption can be seen by inserting this refractive index into the expression for electric field of a plane electromagnetic wave traveling in the  -direction. We can do this by relating the wave number to the refractive index through

-direction. We can do this by relating the wave number to the refractive index through  , with

, with  being the vacuum wavelength. With complex wave number

being the vacuum wavelength. With complex wave number  and refractive index

and refractive index  this can be inserted into the plane wave expression as

this can be inserted into the plane wave expression as

Here we see that  gives an exponential decay, as expected from the Beer–Lambert law. Since intensity is proportional to the square of the electric field, the absorption coefficient becomes

gives an exponential decay, as expected from the Beer–Lambert law. Since intensity is proportional to the square of the electric field, the absorption coefficient becomes  .

.

κ is often called the extinction coefficient in physics although this has a different definition within chemistry. Both n and κ are dependent on the frequency. In most circumstances  (light is absorbed) or

(light is absorbed) or  (light travels forever without loss). In special situations, especially in the gain medium of lasers, it is also possible that

(light travels forever without loss). In special situations, especially in the gain medium of lasers, it is also possible that  , corresponding to an amplification of the light.

, corresponding to an amplification of the light.

An alternative convention uses  instead of

instead of  , but where

, but where  still corresponds to loss. Therefore these two conventions are inconsistent and should not be confused. The difference is related to defining sinusoidal time dependence as

still corresponds to loss. Therefore these two conventions are inconsistent and should not be confused. The difference is related to defining sinusoidal time dependence as  versus

versus  . See Mathematical descriptions of opacity.

. See Mathematical descriptions of opacity.

Dielectric loss and non-zero DC conductivity in materials cause absorption. Good dielectric materials such as glass have extremely low DC conductivity, and at low frequencies the dielectric loss is also negligible, resulting in almost no absorption (κ ≈ 0). However, at higher frequencies (such as visible light), dielectric loss may increase absorption significantly, reducing the material's transparency to these frequencies.

The real and imaginary parts of the complex refractive index are related through the Kramers–Kronig relations. For example, one can determine a material's full complex refractive index as a function of wavelength from an absorption spectrum of the material.

For x-ray and extreme ultraviolet radiation the complex refractive index deviates only slightly from unity and usually has a real part smaller than 1. It is therefore normally written as  (or

(or  ).[3]

).[3]

Relations to other quantities

Optical path length

Optical path length (OPL) is the product of the geometric length d of the path light follows through a system, and the index of refraction of the medium through which it propagates,  . This is an important concept in optics because it determines the phase of the light and governs interference and diffraction of light as it propagates.

. This is an important concept in optics because it determines the phase of the light and governs interference and diffraction of light as it propagates.

Refraction

. Since the phase velocity is lower in the second medium (

. Since the phase velocity is lower in the second medium ( ), the angle of refraction

), the angle of refraction  is less than the angle of incidence

is less than the angle of incidence  ; that is, the ray in the higher-index medium is closer to the normal.

; that is, the ray in the higher-index medium is closer to the normal.When light moves from one medium to another as in the figure to the right, it changes direction, i.e. it is refracted. If it goes from a medium with refractive index  to one with refractive index

to one with refractive index  , with an incidence angle to the surface normal of

, with an incidence angle to the surface normal of  , the refraction angle

, the refraction angle  can be calculated from Snell's law:

can be calculated from Snell's law:

.

.

When light enters a material with higher refractive index, the angle of refraction will be smaller than the angle of incidence and the light will be refracted towards the normal of the surface. The higher the refractive index, the closer to the normal direction the light will travel. When passing into a medium with lower refractive index, the light will instead be refracted away from the normal, towards the surface.

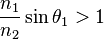

Total internal reflection

If there is no angle  fulfilling Snell's law, i.e.,

fulfilling Snell's law, i.e.,

,

,

the light cannot be transmitted and will instead undergo total internal reflection. This occurs only when going to a less optically dense material, i.e., one with lower refractive index. To get total internal reflection the angles of incidence  must be larger than the critical angle

must be larger than the critical angle

.

.

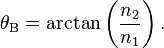

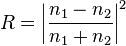

Reflectivity

Apart from the transmitted light there is also a reflected part. The reflection angle is equal to the incidence angle, and the amount of light that is reflected is determined by the reflectivity of the surface. The reflectivity can be calculated from the refractive index and the incidence angle with the Fresnel equations, which for normal incidence reduces to

.

.

For common glass in air,  and

and  , and thus about 4% of the incident power is reflected.[17]

At other incidence angles the reflectivity will also depend on the polarization of the incoming light. At a certain angle called Brewster's angle, p-polarized light (light with the electric field in the plane of incidence) will be totally transmitted. Brewster's angle can be calculated from the two refractive indices of the interface as [2]

, and thus about 4% of the incident power is reflected.[17]

At other incidence angles the reflectivity will also depend on the polarization of the incoming light. At a certain angle called Brewster's angle, p-polarized light (light with the electric field in the plane of incidence) will be totally transmitted. Brewster's angle can be calculated from the two refractive indices of the interface as [2]

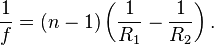

Lenses

The focal length of a lens is determined by its refractive index  and the radii of curvature

and the radii of curvature  and

and  of its surfaces. The power of a thin lens in air is given by the Lensmaker's formula:[2]

of its surfaces. The power of a thin lens in air is given by the Lensmaker's formula:[2]

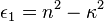

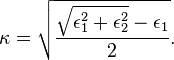

Dielectric constant

The refractive index of electromagnetic radiation equals

where  is the material's relative permittivity, and μr is its relative permeability. For most naturally occurring materials, μr is very close to 1 at optical frequencies,[18] therefore n is approximately

is the material's relative permittivity, and μr is its relative permeability. For most naturally occurring materials, μr is very close to 1 at optical frequencies,[18] therefore n is approximately  .

.

The frequency dependent dielectric constant is simply the square of the (complex) refractive index in a non-magnetic medium (one with a relative permeability of unity). The refractive index is used for optics in Fresnel equations and Snell's law; while the dielectric constant is used in Maxwell's equations and electronics.

Where  is the complex dielectric constant with real and imaginary parts

is the complex dielectric constant with real and imaginary parts  and

and  , and

, and  and

and  are the real and imaginary parts of the refractive index, all functions of frequency:

are the real and imaginary parts of the refractive index, all functions of frequency:

Conversion between refractive index and dielectric constant is done by:

Density

In general, the refractive index of a glass increases with its density. However, there does not exist an overall linear relation between the refractive index and the density for all silicate and borosilicate glasses. A relatively high refractive index and low density can be obtained with glasses containing light metal oxides such as Li2O and MgO, while the opposite trend is observed with glasses containing PbO and BaO as seen in the diagram at the right.

Many oils (such as olive oil) and ethyl alcohol are examples of liquids which are more refractive, but less dense, than water, contrary to the general correlation between density and refractive index.

For gases,  is proportional to the density of the gas as long as the chemical composition does not change.[20]

This means that it is also proportional to the pressure and inversely proportional to the temperature for ideal gases.

is proportional to the density of the gas as long as the chemical composition does not change.[20]

This means that it is also proportional to the pressure and inversely proportional to the temperature for ideal gases.

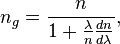

Group index

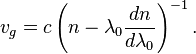

Sometimes, a "group velocity refractive index", usually called the group index is defined:

where vg is the group velocity. This value should not be confused with n, which is always defined with respect to the phase velocity. When the dispersion is small, the group velocity can be linked to the phase velocity by the relation[21]

In this case the group index can thus be written in terms of the wavelength dependence of the refractive index as

where  is the wavelength in the medium.

is the wavelength in the medium.

When the refractive index of a medium is known as a function of the vacuum wavelength (instead of the wavelength in the medium), the corresponding expressions for the group velocity and index are (for all values of dispersion) [22]

where  is the wavelength in vacuum.

is the wavelength in vacuum.

Momentum (Abraham–Minkowski controversy)

In 1908, Hermann Minkowski calculated the momentum of a refracted ray, p, where E is energy of the photon, c is the speed of light in vacuum and n is the refractive index of the medium as follows:[23]

In 1909, Max Abraham proposed the following formula for this calculation:[24]

A 2010 study suggested that both equations are correct, with the Abraham version being the kinetic momentum and the Minkowski version being the canonical momentum, and claims to explain the contradicting experimental results using this interpretation.[25]

Other relations

As shown in the Fizeau experiment, when light is transmitted through a moving medium, its speed relative to a stationary observer is:

The refractive index of a substance can be related to its polarizability with the Lorentz–Lorenz equation or to the molar refractivities of its constituents by the Gladstone–Dale relation.

Refractivity

In atmospheric applications, the refractivity is defined as N = 106(n – 1).[26] The 106 factor is chosen because for air, n deviates from unity at most a few parts per ten thousand.

Molar refractivity, on the other hand, is a measure of the total polarizability of a mole of a substance and can be calculated from the refractive index as

where ρ is the density, and M is the molecular mass.[27]

Nonscalar, nonlinear, or nonhomogeneous refraction

So far, we have assumed that refraction is given by linear equations involving a spatially constant, scalar refractive index. These assumptions can break down in different ways, to be described in the following subsections.

Birefringence

In some materials the refractive index depends on the polarization and propagation direction of the light. This is called birefringence or optical anisotropy.

In the simplest form, uniaxial birefringence, there is only one special direction in the material. This axis is known as the optical axis of the material. Light with linear polarization perpendicular to this axis will experience an ordinary refractive index  while light polarized in parallel will experience an extraordinary refractive index

while light polarized in parallel will experience an extraordinary refractive index  . The birefringence of the material is the difference between these indices of refraction,

. The birefringence of the material is the difference between these indices of refraction,  . Light propagating in the direction of the optical axis will not be affected by the birefringence since the refractive index will be

. Light propagating in the direction of the optical axis will not be affected by the birefringence since the refractive index will be  independent of polarization. For other propagation directions the light will split into two linearly polarized beams. For light traveling perpendicularly to the optical axis the beams will have the same direction. This can be used to change the polarization direction of linearly polarized light or to convert between linear, circular and elliptical polarizations with waveplates.

independent of polarization. For other propagation directions the light will split into two linearly polarized beams. For light traveling perpendicularly to the optical axis the beams will have the same direction. This can be used to change the polarization direction of linearly polarized light or to convert between linear, circular and elliptical polarizations with waveplates.

Many crystals are naturally birefringent, but isotropic materials such as plastics and glass can also often be made birefringent by introducing a preferred direction through, e.g., an external force or electric field. This can be utilized in the determination of stresses in structures using photoelasticity. The birefringent material is then placed between crossed polarizers. A change in birefringence will alter the polarization and thereby the fraction of light that is transmitted through the second polarizer.

In the more general case of trirefringent materials described by the field of crystal optics, the dielectric constant is a rank-2 tensor (a 3 by 3 matrix). In this case the propagation of light cannot simply be described by refractive indices except for polarizations along principal axes.

In materials symultaneously lacking time-reversal and spatial inversion symmetry (for example multiferroics), refractive indices can be different even for counter-propagating light beams, which effect is termed as directional birefringence.[28]

Nonlinearity

The strong electric field of high intensity light (such as output of a laser) may cause a medium's refractive index to vary as the light passes through it, giving rise to nonlinear optics. If the index varies quadratically with the field (linearly with the intensity), it is called the optical Kerr effect and causes phenomena such as self-focusing and self-phase modulation. If the index varies linearly with the field (which is only possible in materials that do not possess inversion symmetry), it is known as the Pockels effect.

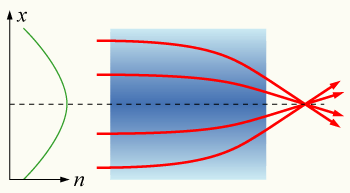

Inhomogeneity

If the refractive index of a medium is not constant, but varies gradually with position, the material is known as a gradient-index medium and is described by gradient index optics. Light traveling through such a medium can be bent or focused, and this effect can be exploited to produce lenses, some optical fibers and other devices. Some common mirages are caused by a spatially varying refractive index of air.

Refractive index measurement

Homogeneous media

The refractive index of liquids or solids can be measured with refractometers. They typically measure some angle of refraction or the critical angle for total internal reflection. The first laboratory refractometers sold commercially were developed by Ernst Abbe in the late 19th century.[29]

The same principles are still used today. In this instrument a thin layer of the liquid to be measured is placed between two prisms. Light is shone through the liquid at incidence angles all the way up to 90°, i.e., light rays parallel to the surface. The second prism should have an index of refraction higher than that of the liquid, so that light only enters the prism at angles smaller than the critical angle for total reflection. This angle can then be measured either by looking through a telescope, or with a digital photodetector placed in the focal plane of a lens. The refractive index  of the liquid can then be calculated from the maximum transmission angle

of the liquid can then be calculated from the maximum transmission angle  as

as  , where

, where  is the refractive index of the prism.[30]

is the refractive index of the prism.[30]

This type of devices are commonly used in chemical laboratories for identification of substances and for quality control. Handheld variants are used in agriculture by, e.g., wine makers to determine sugar content in grape juice, and inline process refractometers are used in, e.g., chemical and pharmaceutical industry for process control.

In gemology a different type of refractometer is used to measure index of refraction and birefringence of gemstones. The gem is placed on a high refractive index prism and illuminated from below. A high refractive index contact liquid is used to achieve optical contact between the gem and the prism. At small incidence angles most of the light will be transmitted into the gem, but at high angles total internal reflection will occur in the prism. The critical angle is normally measured by looking through a telescope.[31]

Refractive index variations

To measure the spatial variation of refractive index in a sample phase-contrast imaging methods are used. These methods measure the variations in phase of the light wave exiting the sample. The phase is proportional to the optical path length the light ray has traversed, and thus gives a measure of the integral of the refractive index along the ray path. The phase cannot be measured directly at optical or higher frequencies, and therefore needs to be converted into intensity by interference with a reference beam. In the visual spectrum this is done using Zernike phase-contrast microscopy, differential interference contrast microscopy (DIC) or interferometry.

Zernike phase-contrast microscopy introduces a phase shift to the low spatial frequency components of the image with a phase-shifting annulus in the Fourier plane of the sample, so that higher frequency parts of the image can interfere with the low frequency reference beam. In DIC the illumination is split up into two beams that are given different polarizations, are phase shifted differently, and are shifted transversely with slightly different amounts. After the specimen the two parts are made to interfere giving an image of the derivative of the optical path length in the direction of the difference in transverse shift.[32] In interferometry the illumination is split up into two beams by a partially reflective mirror. One of the beams is let through the sample before they are combined to interfere and give a direct image of the phase shifts. If the optical path length variations are more than a wavelength the image will contain fringes.

There exist several phase-contrast x-ray imaging techniques to determine 2D or 3D spatial distribution of refractive index of samples in the x-ray regime.[33]

Applications

The refractive index of a material is the most important property of any optical system that uses refraction. It is used to calculate the focusing power of lenses, and the dispersive power of prisms. It can also be used as a useful tool to differentiate between different types of gemstone, due to the unique chatoyance each individual stone displays.

Since refractive index is a fundamental physical property of a substance, it is often used to identify a particular substance, confirm its purity, or measure its concentration. Refractive index is used to measure solids (glasses and gemstones), liquids, and gases. Most commonly it is used to measure the concentration of a solute in an aqueous solution. A refractometer is the instrument used to measure refractive index. For a solution of sugar, the refractive index can be used to determine the sugar content (see Brix).

In GPS, the index of refraction is utilized in ray-tracing to account for the radio propagation delay due to the Earth's electrically neutral atmosphere. It is also used in Satellite link design for the Computation of radiowave attenuation in the atmosphere.

See also

References

- ↑ "Calculation of the Refractive Index of Glasses". Statistical Calculation and Development of Glass Properties.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Hecht, Eugene (2002). Optics. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-321-18878-0.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Attwood, David (1999). Soft x-rays and extreme ultraviolet radiation: principles and applications. p. 60. ISBN 0-521-02997-X.

- ↑ Kinsler, Lawrence E. (2000). Fundamentals of Acoustics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 136. ISBN 0-471-84789-5.

- ↑ Young, Thomas (1807). A course of lectures on natural philosophy and the mechanical arts. p. 413.

- ↑ Newton, Isaac (1730). Opticks: Or, A Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of Light. p. 247.

- ↑ Hauksbee, Francis (1710). "A Description of the Apparatus for Making Experiments on the Refractions of Fluids". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 27 (325–336): 207. doi:10.1098/rstl.1710.0015.

- ↑ Hutton, Charles (1795). Philosophical and mathematical dictionary. p. 299.

- ↑ von Fraunhofer, Joseph (1817). "Bestimmung des Brechungs und Farbenzerstreuungs Vermogens verschiedener Glasarten". Denkschriften der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu München 5: 208. Exponent des Brechungsverhältnisses is index of refraction

- ↑ Brewster, David (1815). "On the structure of doubly refracting crystals". Philosophical Magazine 45: 126.

- ↑ Herschel, John F.W. (1828). On the Theory of Light. p. 368.

- ↑ Tabata, M. et al. (2005). "Development of Silica Aerogel with Any Density". 2005 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record.

- ↑ Naoki Sadayori and Yuji Hotta "Polycarbodiimide having high index of refraction and production method thereof" US patent 2004/0158021 A1 (2004)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "X-Ray Interactions With Matter". The Center for X-Ray Optics. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ↑ Hecht, Eugene (2002). Optics. Addison-Wesley. p. 67. ISBN 0-321-18878-0.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Feynman, Richard P. (2011). Feynman Lectures on Physics 1: Mainly Mechanics, Radiation, and Heat. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465024933.

- ↑ Swenson, Jim; Incorporates Public Domain material from the U.S. Department of Energy (November 10, 2009). "Refractive Index of Minerals". Newton BBS, Argonne National Laboratory, US DOE. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ Urzhumov, Yaroslav A.; Urzhumov, Yaroslav A (2005). "Electric and magnetic properties of sub-wavelength plasmonic crystals". Journal of Optics A: Pure and Applied Optics 7 (2): S23. Bibcode:2005JOptA...7S..23S. doi:10.1088/1464-4258/7/2/003.

- ↑ Wooten, Frederick (1972). Optical Properties of Solids. New York City: Academic Press. p. 49. ISBN 0-12-763450-9.(online pdf)

- ↑ Stone, Jack A.; Zimmerman, Jay H. (2011-12-28). "Index of refraction of air". Engineering metrology toolbox. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- ↑ Born, Max and Wolf, Emil (2000). Principles of Optics, 7th (expanded) edition. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-521-78449-8.

- ↑ Bor, Z.; Osvay, K.; Rácz, B.; Szabó, G. (1990). "Group refractive index measurement by Michelson interferometer". Optics Communications 78 (2): 109–112. Bibcode:1990OptCo..78..109B. doi:10.1016/0030-4018(90)90104-2.

- ↑ Minkowski, Hermann (1908). "Die Grundgleichung für die elektromagnetischen Vorgänge in bewegten Körpern". Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse: 53–111.

- ↑ Abraham, Max (1909). "Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper". Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo 28 (1).

- ↑ Barnett, Stephen (2010-02-07). "Resolution of the Abraham-Minkowski Dilemma". Phys. Rev. Lett. 104 (7): 070401. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.104g0401B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.070401. PMID 20366861.

- ↑ Aparicio, Josep M.; Laroche, Stéphane (2011-06-02). "An evaluation of the expression of the atmospheric refractivity for GPS signals". Journal of Geophysical Research (American Geophysical Union) 116 (D11): D11104. doi:10.1029/2010JD015214. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Born, Max; Wolf, Emil (1999). Principles of Optics: Electromagnetic Theory of Propagation, Interference and Diffraction of Light (7th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0-521-64222-1.

- ↑

- ↑ "The Evolution of the Abbe Refractometer". Humboldt State University, Richard A. Paselk. 1998. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ "Refractometers and refractometry". Refractometer.pl. 2011. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ "Refractometer". The Gemology Project. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ Carlsson, Kjell (2007). "Light microscopy". Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Richard (July 2000). "Phase‐Sensitive X‐Ray Imaging". Physics Today 53 (7): 23. Bibcode:2000PhT....53g..23F. doi:10.1063/1.1292471.

External links

- NIST calculator for determining the refractive index of air

- Dielectric materials

- Science World

- Filmetrics' online database Free database of refractive index and absorption coefficient information

- RefractiveIndex.INFO Refractive index database featuring online plotting and parameterisation of data

- sopra-sa.com Refractive index database as text files (sign-up required)

- LUXPOP Thin film and bulk index of refraction and photonics calculations