Redundant binary representation

A redundant binary representation (RBR) is a numeral system that uses more bits than needed to represent a single binary digit so that most numbers have several representations. A RBR is unlike usual binary numeral systems, including two's complement, which use a single bit for each digit. Many of a RBR's properties differ from those of regular binary representation systems. Most importantly, a RBR allows addition without using a typical carry.[1] When compared to non-redundant representation, a RBR makes bitwise logical operation slower, but arithmetic operations are faster when a greater bit width is used.[2] Usually, each digit has its own sign that is not necessarily the same as the sign of the number represented. When digits have signs, that RBR is also a signed-digit representation.

Conversion from RBR

A RBR is a place-value notation system. In a RBR, digits are pairs of bits, that is, for every place, a RBR uses a pair of bits. The value represented by an RBR digit can be found using a translation table. This table indicates the mathematical value of each possible pair of bits.

As in conventional binary representation, the integer value of a given representation is a weighted sum of the values of the digits. The weight starts at 1 for the rightmost position and goes up by a factor of 2 for each next position. Usually, a RBR allows negative values. There is no single sign bit that tells if a RBR represented number is positive or negative. Most integers have several possible representations in an RBR.

Often one of the several possible representations of an integer is chosen as the "canonical" form, so each integer has only one possible "canonical" representation -- non-adjacent form and two's complement are a popular choices for that canonical form.

An integer value can be converted back from a RBR using the following formula, where n is the number of digit and dk is the interpreted value of the k-th digit, where k starts at 0 at the rightmost position:

The conversion from a RBR to two's complement can be done in O(log(n)) using prefix adder where n is the number of digit.[3]

Example of redundant binary representation

| Digit | Interpreted value |

|---|---|

| 00 | −1 |

| 01 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 |

| 11 | 1 |

Not all RBR have the same properties. For example, using the translation table on the right, the number 1 can be represented in this RBR in many ways: "01·01·01·11", "01·01·10·11", "01·01·11·00", "11·00·00·00". Also, for this translation table, flipping all bits (NOT gate) corresponds to finding the additive inverse (multiplication by −1) of the integer represented.[4]

In this case:

Arithmetic operations

A RBR is used by particular arithmetic logic units.

In particular, a carry-save adder uses a RBR.

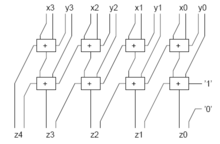

Addition

The addition operation in all RBRs is carry-free, which means that the carry does not have to propagate through all the width of the addition unit. In effect, the addition in all RBRs is a constant-time operation. The addition will always take the same amount of time independent of the bit width of the operands. This does not imply that the addition is always faster in a RBR than is two's complement representation, but that the addition will eventually be faster in a RBR with increasing bit width because the two's complement addition unit's delay is proportional to log(n) (where n is the bit width).[5] The addition in a RBR take a constant time because each digit of the result can be calculated independently of one another, implying that each digit of the result can be calculated in parallel. A few of the adders can be found here [6]

Subtraction

Subtraction is the same as the addition except that the additive inverse of the second operand needs to be computed first. The additive inverse is usually found using a translation table.

Logical operations

Implementing logical operations in a RBR using digital logic is more complicated than in usual representations. For example, the expected result of the bitwise AND operation on a pair of representations of 1 is expected to have value 1 in usual representations. Since there are many ways to represent 1 in a RBR, it is not possible to simply use the basic logic gate AND between every digit. The same problem apply to the OR and XOR operations. While it is possible to do bitwise operations directly on the underlying bits inside a RBR, it is not clear that this is a meaningful operation. Assuming one wants the result to represent the same integer value as if the operation had been carried out using a standard non-redundant binary representation, it is necessary to convert the two operands first to non-redundant representations. Consequently, logical operations are slower in a RBR. More precisely, they take a time proportional to log(n) (where n is the number of digit) compared to a constant-time in two's complement.

References

- ↑ Dhananjay Phatak, I. Koren, Hybrid Signed-Digit Number Systems: A Unified Framework for Redundant Number Representations with Bounded Carry Propagation Chains, 1994,

- ↑ Louis-Philippe Lessard, Fast Arithmetic on FPGA Using Redundant Binary Apparatus, 2008,

- ↑ Sreehari Veeramachaneni, M.Kirthi Krishna, Lingamneni Avinash, Sreekanth Reddy P, M.B. Srinivas, Novel High-Speed Redundant Binary to Binary converter using Prefix Networks, 2007,

- ↑ Marcel Lapointe, Huu Tue Huynh, Paul Fortier. Systematic Design of Pipelined Recursive Filters. s.l. : IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTERS, 1993.

- ↑ Yu-Ting Pai, Yu-Kumg Chen, The fastest carry lookahead adder, 2004

- ↑ Bijoy Jose and Damu Radhakrishnan, Delay Optimized Redundant Binary Adders