Recoil

.jpg)

Recoil (often called knockback, kickback or simply kick) is the backward momentum of a gun when it is discharged. In technical terms, the recoil caused by the gun exactly balances the forward momentum of the projectile and exhaust gasses (ejecta), according to Newton's third law. In most small arms, the momentum is transferred to the ground through the body of the shooter; while in heavier guns such as mounted machine guns or cannons, the momentum is transferred to the ground through its mount. In order to bring the gun to a halt, a forward counter-recoil force must be applied to the gun over a period of time. Generally, the counter-recoil force is smaller than the recoil force, and is applied over a time period that is longer than the time that the recoil force is being applied (i.e. the time during which the ejecta are still in the barrel of the gun). This imbalance of forces causes the gun to move backward until it is motionless.

A change in momentum results in a force, which according to Newton's second law is equal to the time derivative of the momentum of the gun. The momentum is equal to the mass of the gun multiplied by its velocity. This backward momentum is equal in magnitude, by the law of conservation of momentum, to the forward momentum of the ejecta (projectile(s), wad, propellant gases, etc...) from the gun. If the mass and velocity of the ejecta are known, it is possible to calculate a gun’s momentum and thus the energy. In practice, it is often simpler to derive the gun’s energy directly with a reading from a ballistic pendulum or ballistic chronograph.

Recoil: momentum, energy and impulse

Momentum

There are two conservation laws at work when a gun is fired: conservation of momentum and conservation of energy. Recoil is explained by the law of conservation of momentum, and so it is easier to discuss it separately from energy.

The nature of the recoil process is determined by the force of the expanding gases in the barrel upon the gun (recoil force), which is equal and opposite to the force upon the ejecta. It is also determined by the counter-recoil force applied to the gun (e.g. an operators hand or shoulder, or a mount, in the case of a mounted gun). The recoil force only acts during the time that the ejecta are still in the barrel of the gun. The counter-recoil force is generally applied over a certain time period and adds forward momentum to the gun equal to the backward momentum supplied by the recoil force, in order to bring the gun to a halt. There are two special cases of counter recoil force: Free-recoil, in which the time duration of the counter-recoil force is very much larger than the duration of the recoil force, and zero-recoil, in which the counter-recoil force matches the recoil force in magnitude and duration. Except for the case of zero-recoil, the counter-recoil force is smaller than the recoil force but lasts for a longer time. Since the recoil force and the counter-recoil force are not matched, the gun will move rearward, slowing down until it comes to rest. In the zero-recoil case, the two forces are matched and the gun will not move when fired. In most cases, a gun is very close to a free-recoil condition, since the recoil process generally lasts much longer than the time needed to move the ejecta down the barrel. An example of near zero-recoil would be a gun securely clamped to a massive or well-anchored table, or supported from behind by a massive wall.

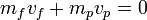

The recoil of a firearm, whether large or small, is a result of the law of conservation of momentum. Assuming that the firearm and projectile are both at rest before firing, then their total momentum is zero. Assuming a near free-recoil condition, and neglecting the gases ejected from the barrel, then immediately after firing, conservation of momentum requires that the total momentum of the firearm and projectile is the same as before, namely zero. Stating this mathematically:

where  is the momentum of the firearm and

is the momentum of the firearm and  is the momentum of the projectile. In other words, immediately after firing, the momentum of the firearm is equal and opposite to the momentum of the projectile.

is the momentum of the projectile. In other words, immediately after firing, the momentum of the firearm is equal and opposite to the momentum of the projectile.

Since momentum of a body is defined as its mass multiplied by its velocity, we can rewrite the above equation as:

where:

is the mass of the firearm

is the mass of the firearm is the velocity of the firearm immediately after firing

is the velocity of the firearm immediately after firing is the mass of the projectile

is the mass of the projectile is the velocity of the projectile immediately after firing

is the velocity of the projectile immediately after firing

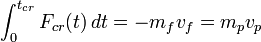

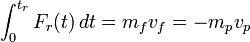

A force integrated over the time period during which it acts will yield the momentum supplied by that force. The counter-recoil force must supply enough momentum to the firearm to bring it to a halt. This means that:

where:

is the counter-recoil force as a function of time (t)

is the counter-recoil force as a function of time (t) is duration of the counter-recoil force

is duration of the counter-recoil force

A similar equation can be written for the recoil force on the firearm:

where:

is the recoil force as a function of time (t)

is the recoil force as a function of time (t) is duration of the recoil force

is duration of the recoil force

Assuming the forces are somewhat evenly spread out over their respective durations, the condition for free-recoil is  , while for zero-recoil,

, while for zero-recoil,  .

.

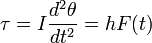

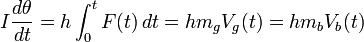

Angular momentum

For a gun firing under free-recoil conditions, the force on the gun will not only force the gun backwards, but will also cause it to rotate about its center of mass. The torque ( ) on the gun is given by:

) on the gun is given by:

where h is the perpendicular distance of the center of mass of the gun below the barrel axis, F(t) is the force on the gun due to the expanding gases, equal and opposite to the force on the bullet, I is the moment of inertia of the gun about its center of mass, and  is the angle of rotation of the barrel axis "up" from its orientation at ignition (aim angle). The angular momentum of the gun is found by integrating this equation to obtain:

is the angle of rotation of the barrel axis "up" from its orientation at ignition (aim angle). The angular momentum of the gun is found by integrating this equation to obtain:

where the equality of the momenta of the gun and bullet have been used. The angular rotation of the gun as the bullet exits the barrel is then found by integrating again:

where  is the angle above the aim angle at which the bullet leaves the barrel,

is the angle above the aim angle at which the bullet leaves the barrel,  is the time of travel of the bullet in the barrel and L is the distance the bullet travels from its rest position to the tip of the barrel. The angle at which the bullet leaves the barrel above the aim angle is then given by:

is the time of travel of the bullet in the barrel and L is the distance the bullet travels from its rest position to the tip of the barrel. The angle at which the bullet leaves the barrel above the aim angle is then given by:

The momentum of the ejected gases will not contribute very much to this result, since much of the ejected gases exit the barrel after the bullet has left the barrel.

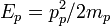

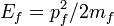

Energy

A consideration of energy leads to a different equation. From Newton's second law, the energy of a moving body due to its motion can be stated mathematically from the translational kinetic energy as:

where:

is the translational kinetic energy

is the translational kinetic energy is the mass of the body

is the mass of the body is its velocity

is its velocity is its momentum (mv)

is its momentum (mv)

This equation is known as the "classic statement" and yields a measurement of energy in joules (or foot-pound force in non-SI units).  is the amount of work that can be done by the recoiling firearm, firearm system, or projectile because of its motion, and is also called the translational kinetic energy. In the firearms lexicon, the energy of a recoiling firearm is called felt recoil, free recoil, and recoil energy. This same energy from a projectile in motion is called: muzzle energy, bullet energy, remaining energy. The energy of the projectile at the point of impact is known as the down range energy or impact energy and generally will be slightly smaller than the muzzle energy due to wind resistance acting upon the projectile.

is the amount of work that can be done by the recoiling firearm, firearm system, or projectile because of its motion, and is also called the translational kinetic energy. In the firearms lexicon, the energy of a recoiling firearm is called felt recoil, free recoil, and recoil energy. This same energy from a projectile in motion is called: muzzle energy, bullet energy, remaining energy. The energy of the projectile at the point of impact is known as the down range energy or impact energy and generally will be slightly smaller than the muzzle energy due to wind resistance acting upon the projectile.

Again assuming free-recoil conditions and assuming all forward momentum is due to the projectile, the energy of the projectile will be  and the energy of the firearm due to recoil will be

and the energy of the firearm due to recoil will be  . Since, by Newton's third law,

. Since, by Newton's third law,  , it follows that the ratios of the energies is given by:

, it follows that the ratios of the energies is given by:

The mass of the firearm ( ) is generally much greater than the projectile mass (

) is generally much greater than the projectile mass ( ) which means that most of the kinetic energy produced by the firing of the firearm is given to the projectile. For example, a rifle weighing 5 pounds firing a 150 grain bullet, the recoil energy will be only 0.43 percent of the total kinetic energy developed. In the case of zero-recoil, the firearm will gain no energy, and the energy of the projectile will be increased by 0.43 percent over that of the free-recoil case.

) which means that most of the kinetic energy produced by the firing of the firearm is given to the projectile. For example, a rifle weighing 5 pounds firing a 150 grain bullet, the recoil energy will be only 0.43 percent of the total kinetic energy developed. In the case of zero-recoil, the firearm will gain no energy, and the energy of the projectile will be increased by 0.43 percent over that of the free-recoil case.

The recoil energy is generally absorbed by the mechanism which produces the counter-recoil force, and is dissipated as heat. For a hand-held firearm, the energy is absorbed by the shooter's body, creating a small amount of heat. For the naval cannon from the figure above, it will roll backwards and the recoil energy will be mostly absorbed by the friction forces in the wheel axles and between the wheel and the ship deck and this energy is again converted to heat.

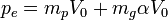

Including the ejected gas

The backward momentum applied to the firearm is actually equal and opposite to the momentum of not only the projectile, but the ejected gas created by the combustion of the charge as well. Likewise, the recoil energy given to the firearm is affected by the ejected gas. By conservation of mass, the mass of the ejected gas will be equal to the original mass of the propellant. As a rough approximation, the ejected gas can be considered to have an effective exit velocity of  where

where  is the muzzle velocity of the projectile and

is the muzzle velocity of the projectile and  is approximately constant. The total momentum

is approximately constant. The total momentum  of the propellant and projectile will then be:

of the propellant and projectile will then be:

where:  is the mass of the propellant charge, equal to the mass of the ejected gas.

is the mass of the propellant charge, equal to the mass of the ejected gas.

This expression should be substituted into the expression for projectile momentum in order to obtain more a more accurate description of the recoil process. The effective velocity may be used in the energy equation as well, but since the value of α used is generally specified for the momentum equation, the energy values obtained may be less accurate. The value of the constant α is generally taken to lie between 1.25 and 1.75. It is mostly dependent upon the type of propellant used, but may depend slightly on other things such as the ratio of the length of the barrel to its radius.

Perception of recoil

For small arms, the way in which the shooter perceives the recoil, or kick, can have a significant impact on the shooter's experience and performance. For example, a gun that is said to "kick like a mule" is going to be approached with trepidation, and the shooter will anticipate the recoil and flinch in anticipation as the shot is released. This leads to the shooter jerking the trigger, rather than pulling it smoothly, and the jerking motion is almost certain to disturb the alignment of the gun and result in a miss.

This perception of recoil is related to the acceleration associated with a particular gun. The actual recoil is associated with the momentum of a gun, the momentum being the product of the mass of the gun times the reverse velocity of the gun. A heavier gun, that is a gun with more mass, will manifest the momentum by exhibiting a lessened acceleration, and, generally, result in a lessened perception of recoil.

One of the common ways of describing the felt recoil of a particular gun-cartridge combination is as "soft" or "sharp" recoiling; soft recoil is recoil spread over a longer period of time, that is at a lower acceleration, and sharp recoil is spread over a shorter period of time, that is with a higher acceleration. With the same gun and two loads with different bullet masses but the same recoil force, the load firing the heavier bullet will have the softer recoil, because the product of mass times acceleration must remain constant, and if mass goes up then acceleration must go down, to keep the product constant.

Keeping the above in mind, you can generally base the relative recoil of firearms by factoring in a number of figures such as bullet weight, powder charge, the weight of the actual firearm etc. The following are base examples calculated through the Handloads.com free online calculator, and bullet and firearm data from respective reloading manuals (of medium/common loads) and manufacturer specs:

- In a Glock 22 frame, using the empty weight of 1.43 lb (0.65 kg), the following was obtained:

- 9 mm Luger: Recoil Impulse of 0.78 ms; Recoil Velocity of 17.55 ft/s (5.3 m/s); Recoil Energy of 6.84 ft·lbf (9.3 J)

- .357 SIG: Recoil Impulse of 1.06 ms; Recoil velocity of 23.78 ft/s (7.2 m/s); Recoil Energy of 12.56 ft·lbf (17.0 J)

- .40 S&W: Recoil impulse of 0.88 ms; Recoil velocity of 19.73 ft/s (6.0 m/s); Recoil Energy of 8.64 ft·lbf (11.7 J)

- In a Smith and Wesson .44 Magnum with 7.5-inch barrel, with an empty weight of 3.125 lb (1.417 kg), the following was obtained:

- .44 Remington Magnum: Recoil impulse of 1.91 ms; Recoil velocity of 19.69 ft/s (6.0 m/s); Recoil Energy of 18.81 ft·lbf (25.5 J)

- In a Smith and Wesson 460 7.5-inch barrel, with an empty weight of 3.5 lb (1.6 kg), the following was obtained:

- .460 S&W Magnum: Recoil Impulse of 3.14 ms; Recoil Velocity of 28.91 ft/s (8.8 m/s); Recoil Energy of 45.43 ft·lbf (61.6 J)

- In a Smith and Wesson 500 4.5-inch barrel, with an empty weight of 3.5 lb (1.6 kg), the following was obtained:

- .500 S&W Magnum: Recoil Impulse of 3.76 ms; Recoil Velocity of 34.63 ft/s (10.6 m/s); Recoil Energy of 65.17 ft·lbf (88.4 J)

In addition to the overall mass of the gun, reciprocating parts of the gun will affect how the shooter perceives recoil. While these parts are not part of the ejecta, and do not alter the overall momentum of the system, they do involve moving masses during the operation of firing. For example, gas-operated shotguns are widely held to have a "softer" recoil than fixed breech or recoil-operated guns. In a gas-operated gun, the bolt is accelerated rearwards by propellant gases during firing, which results in a forward force on the body of the gun. This is countered by a rearward force as the bolt reaches the limit of travel and moves forwards, resulting in a zero sum, but to the shooter, the recoil has been spread out over a longer period of time, resulting in the "softer" feel.[1]

Mounted guns

A recoil system absorbs recoil energy, reducing the peak force that is conveyed to whatever the gun is mounted on. Old-fashioned cannons without a recoil system roll several meters backwards when fired. First was introduced in Russia as Baranovsky gun pl:Oporopowrotnik by Wladimir Baranovsky ru:Барановский, Владимир Степанович in 1872 (short recoil operation) and later in France (based on Baranovsky construction) - 75mm field gun of 1897 (long recoil operation). The usual recoil system in modern quick-firing guns is the hydro-pneumatic recoil system. In this system, the barrel is mounted on rails on which it can recoil to the rear, and the recoil is taken up by a cylinder which is similar in operation to an automotive gas-charged shock absorber, and is commonly visible as a cylinder mounted parallel to the barrel of the gun, but shorter and smaller than it. The cylinder contains a charge of compressed air, as well as hydraulic oil; in operation, the barrel's energy is taken up in compressing the air as the barrel recoils backward, then is dissipated via hydraulic damping as the barrel returns forward to the firing position. The recoil impulse is thus spread out over the time in which the barrel is compressing the air, rather than over the much narrower interval of time when the projectile is being fired. This greatly reduces the peak force conveyed to the mount (or to the ground on which the gun has been emplaced).

In a soft-recoil system, the spring (or air cylinder) that returns the barrel to the forward position starts out in a nearly fully compressed position, then the gun's barrel is released free to fly forward in the moment before firing; the charge is then ignited just as the barrel reaches the fully forward position. Since the barrel is still moving forward when the charge is ignited, about half of the recoil impulse is applied to stopping the forward motion of the barrel, while the other half is, as in the usual system, taken up in recompressing the spring. A latch then catches the barrel and holds it in the starting position. This roughly halves the energy that the spring needs to absorb, and also roughly halves the peak force conveyed to the mount, as compared to the usual system. However, the need to reliably achieve ignition at a single precise instant is a major practical difficulty with this system;[2] and unlike the usual hydro-pneumatic system, soft-recoil systems do not easily deal with hangfires or misfires. One of the early guns to use this system was the French 65 mm mle.1906; it was also used by the World War II British PIAT man-portable anti-tank weapon.

Recoilless rifles and rocket launchers exhaust gas to the rear, balancing the recoil. They are used often as light anti-tank weapons. The Swedish-made Carl Gustav 84mm recoilless gun is such a weapon.

In machine guns following Hiram Maxim's design - e.g. the Vickers machine gun - the recoil of the barrel is used to drive the feed mechanism.

Misconceptions about recoil

Hollywood depictions of firearm shooting victims being thrown through several feet backwards are inaccurate, although not for the often-cited reason of conservation of energy. Although energy must be conserved, this does not mean that the kinetic energy of the bullet must be equal to the recoil energy of the gun: in fact, it is many times greater. For example, a bullet fired from an M16 rifle has approximately 1763 Joules of kinetic energy as it leaves the muzzle, but the recoil energy of the gun is less than 7 Joules. Despite this imbalance, energy is still conserved because the total energy in the system before firing (the chemical energy stored in the propellant) is equal to the total energy after firing (the kinetic energy of the recoiling firearm, plus the kinetic energy of the bullet and other ejecta, plus the heat energy from the explosion). In order to work out the distribution of kinetic energy between the firearm and the bullet, it is necessary to use the law of conservation of momentum in combination with the law of conservation of energy.

The same reasoning applies when the bullet strikes a target. The bullet may have a kinetic energy in the hundreds or even thousands of joules, which in theory is enough to lift a person well off the ground. This energy, however, cannot be efficiently given to the target, because total momentum must be conserved, too. Approximately, only a fraction not larger than the inverse ratio of the masses can be transferred. The rest is spent in the deformation or shattering of the bullet (depending on bullet construction), damage to the target (depending on target construction), and heat dissipation. In other words, because the bullet strike on the target is an inelastic collision, a minority of the bullet energy is used to actually impart momentum to the target. This is why a ballistic pendulum relies on conservation of bullet momentum and pendulum energy rather than conservation of bullet energy to determine bullet velocity; a bullet fired into a hanging block of wood or other material will spend much of its kinetic energy to create a hole in the wood and dissipate heat as friction as it slows to a stop.

Gunshot victims frequently do collapse when shot, which is usually due to psychological motives, a direct hit to the central nervous system, and/or massive blood loss (see stopping power), and is not the result of the momentum of the bullet pushing them over.[3]

See also

- Ricochet, a projectile that rebounds, bounces or skips off a surface, potentially backwards toward the shooter

- Recoil buffer

- Muzzle brake

- Recoil pad

References

- Notes

- ↑ Randy Wakeman. "Controlling shotgun recoil". Chuck Hawks.

- ↑ "Soft Recoil System". Field Artillery Bulletin. April 1969, pp. 43-48.

- ↑ Anthony J. Pinizzotto, Ph.D., Harry A. Kern, M.Ed., and Edward F. Davis, M.S. (October 2004). "One-Shot Drops Surviving the Myth". FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin (Federal Bureau of Investigation).

External links

- Recoil Tutorial

- Recoil Calculator and summary of equations at JBM.