Ragnall mac Somairle

| Ragnall mac Somairle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Wife | Fonia |

| Issue | Domnall, Ruaidrí |

| Dynasty | Clann Somairle |

| Father | Somairle mac Gilla Brigte |

| Mother | Ragnhildr Óláfsdóttir |

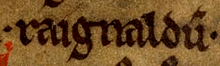

Ragnall mac Somairle[note 3] was a significant late 12th century magnate, seated on the western seaboard of Scotland. He was likely a younger son of Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, Lord of Argyll (d. 1164) and his wife, Ragnhildr, daughter of Óláfr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles (d. 1153). The 12th century Kingdom of the Isles, ruled by Ragnall's father and maternal-grandfather, existed within a hybrid Norse-Gaelic milieu, which bordered an ever strengthening and consolidating Kingdom of Scots.

In the mid 12th century, Somairle rose in power and won the Kingdom of the Isles from his brother-in-law. After Somairle perished in battle against the Scots in 1164, much of his kingdom was likely partitioned between his surviving sons. Ragnall's allotment appears to have been in the southern Hebrides and Kintyre. In time, Ragnall appears to have risen in power and became the leading member of Somairle's descendants, the meic Somairle (or Clann Somairle). Ragnall is known to have styled himself "King of the Isles, Lord of Argyll and Kintyre" and "Lord of the Isles". His claim to the title of king, like other members of the meic Somairle, is derived through Ragnhildr, a member of the Crovan dynasty.

Ragnall disappears from record after he and his sons were defeated by his brother Áengus. Ragnall's death-date is unknown, although dates ranging between 1192–1227 are all possibilities. Surviving contemporary sources reveal that Ragnall was a significant patron of the Church. Although his father appears to have aligned himself with traditional forms of Christianity, Ragnall's associated himself with newer reformed religious orders from the continent. Ragnall's now non-existent seal, which pictured a knight on horseback, also indicates that he attempted to present himself as an up-to-date ruler, not unlike his Anglo-French contemporaries of the bordering Kingdom of Scots.

Ragnall is known to have left two sons, Domnall and Ruaidrí, who went on to found powerful Hebridean families. Either Ragnall or Ruaidrí had daughters who married Ragnall's first cousins Rögnvaldr and Óláfr, two 13th century kings of the Crovan dynasty.

Origins of the meic Somairle

_02.png)

Ragnall was a son of Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, Lord of Argyll (d. 1164) and his wife, Ragnhildr, daughter of Óláfr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles. Somairle and Ragnhildr had at least three sons: Dubgall (d. after 1175), Ragnall, Áengus (d. 1210), and likely a fourth, Amlaíb.[30] Dubgall appears to have been the couple's eldest son.[31][note 4] Little is certain of the origins of Ragnall's father, although his marriage suggests that he belonged to a family of some substance. In the first half of the 12th century, the Hebrides and the Isle of Man (Mann) were encompassed within the Kingdom of the Isles, which was ruled by Somairle's father-in-law, a member of the Crovan dynasty. Somairle's rise to power may well have begun at about this time, as the few surviving sources from the era suggest that Argyll may have begun to slip from the control of David I, King of Scots (d. 1153).[32]

Somairle first appears on record in 1153, when he rose in rebellion with his nephews, the sons of the royal pretender Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair (fl. 1134), against the recently enthroned Máel Coluim IV, King of Scots (d. 1165).[33][note 5] In the same year, Somairle's father-in-law was murdered after ruling the Kingdom of the Isles about forty years. Óláfr was succeeded by his son, Guðrøðr; and sometime afterwards, Somairle participated in a coup within the kingdom by presenting Dubgall as a potential king. In consequence, Somairle and his brother-in-law fought a naval battle in 1156, after which much of the Hebrides appear to have fallen under Somairle's control.[34] Two years later, he defeated Guðrøðar outright and took control of the entire island-kingdom.[35] In 1164, Somairle again rose against the King of Scots, and is recorded in various early sources to have commanded a massive invasion force of men from throughout the Isles, Argyll, Kintyre, and Scandinavian Dublin. Somairle's host sailed up the Clyde, and made landfall near what is today Renfrew, where they were crushed by the Scots, and he himself was slain.[36] Following Somairle's demise, Guðrøðr returned to the Isles and seated himself on Mann, although the Hebridean-territories won by Somairle in 1156 were retained by his descendants, the meic Somairle.[37]

Although contemporary sources are silent on the matter, it is more than likely that on Somairle's demise, his territory was divided amongst his surviving sons.[38] The precise allotment of lands is unknown; even though the division of lands amongst later generations of meic Somairle can be readily discerned, such boundaries are unlikely to have existed during chaotic 12th century. It is possible that the territory of the first generation of meic Somairle may have stretched from Glenelg in the north, to the Mull of Kintyre in the south; with Áengus ruling in the north, Dubgall centred in Lorne (with possibly the bulk of the inheritance), and Ragnall in Kintyre and the southern islands.[39]

Internal conflict

.jpg)

Little is known of Somairle's descendants in the decades following his demise.[40] Dubgall does not appear on record until 1175, when he is attested far from the Isles in Durham.[41] Nothing is certain of Dubgall's later activities, and it is possible that, by the 1180s, Ragnall had begun to encroach upon Dubgall's territories and his position as head of the meic Somairle.[42] In 1192, the Chronicle of Mann records that Ragnall and his sons were defeated in a particularly bloody battle against Áengus.[43] The chronicle does not identify the location of the battle, or elaborate under what circumstances it was fought. However, it is possible that the conflict took place in the northern part of the meic Somairle domain, where some of Áengus' lands may have lain. Although the hostile contact between Ragnall and Áengus could have been result of Ragnall's rise in power at Dubgall's expense,[44] the clash of 1192 may also mark Ragnall's downfall.[45]

One of several ecclesiastical sources that deal specifically with Ragnall is an undated grant to the Cluniac priory at Paisley.[46][note 6] Since this grant likely dates to after Ragnall's defeat to Áengus, it may be evidence of an attempt made by Ragnall to secure an alliance with Alan fitz Walter, Steward of Scotland (d. 1204). The patrons of this priory were members of Alan's own family,[47] a powerful kindred that had recently began to expand its influence westwards from Renfrew, to the frontier of the Scottish realm and the fringes of Argyll.[48][note 7] Since Bute seems to have fallen into the hands of this kindred at about the time of Ragnall's grant, it is possible that Alan took advantage of the internal conflict between the meic Somairle, and seized the island before 1200.[49] Alternately, Alan may have received the island from Ragnall as payment for military support against Áengus, who appears to have gained the upper hand over Ragnall by 1192.[50] Alan's expansion and influence in territories outwith the bounds of the Scottish kingdom may have been perceived as a threat by William I, King of Scots (d. 1214), and may partly explain the king's construction of a royal castle at Ayr in 1195. This fortress extended Scottish royal authority into the outer Firth of Clyde region, and was likely intended to dominate not only William's peripheral barons, but also independent rulers just beyond the borders of the Scottish realm.[51]

Titles and seal

In his charter to Saddell Abbey, Ragnall is styled in Latin rex insularum, dominus de Ergile et Kyntyre[53] ("King of the Isles, Lord of Argyll and Kintyre"),[54] a title which may indicate that Ragnall claimed all of the possessions of his father.[55] In what is likely a later charter,[56] Ragnall is styled in Latin dominus de Inchegal[57] ("Lord of the Isles")[58] in his grant to the priory of Paisley.[note 9] Although Ragnall's abandonment of the title "king" in favour of "lord" may not be significant,[59] it could be connected with his defeat to Áengus, or to the expansion and rise in power of Ragnall's namesake and first cousin Rögnvaldr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles (d. 1229).[60] The style dominus de Inchegal is not unlike dominus Insularum ("Lord of the Isles"), a title first adopted in 1336 by Ragnall's great-great-grandson, Eoin Mac Domhnaill, Lord of the Isles (d. c. 1387), the first of four successive Lords of the Isles.[61]

Ragnall's grant to the priory of Paisley is preserved in two documents: one dates to the late 12th century or early 13th century, and a later copy is contained in an instrument which dates to 1426.[62] Appended to the latter document is a description of a seal impressed in white wax, which the 15th century notary alleged to have belonged to Ragnall. On one side, the seal is described to have depicted a ship, filled with men-at-arms. On the reverse side, the seal was said to have depicted a man on horseback, armed with a sword in his hand.[63]

Ragnall is the only member of the meic Somairle known to have styled himself in documents rex insularum.[64][note 10] His use of both the title and seal are likely derived from those of the leading members of the Crovan dynasty, such as his namesake Rögnvaldr, who not only bore the same title but was said to have borne a similar two-sided seal.[65] The descriptions of the cousins' seals shows that these devices combined the imagery of a Norse-Gaelic galley and an Anglo-French knight. The maritime imagery likely symbolised the power of a ruler of an island-kingdom, and the equestrian imagery appears to have symbolised feudal society, in which the cult of knighthood had reached its peak in the 12th and early 13th centuries.[66] The use of such seals by leading Norse-Gaelic lords, seated on the periphery of the kingdoms of Scotland and England, likely illustrates their desire to present themselves as up-to-date and modern to their contemporaries in Anglo-French society.[67]

Norse-Gaelic namesake

| Affraic | Óláfr | Ingibjörg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Guðrøðr | Ragnhildr | Somairle | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rögnvaldr | Ragnall | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The fact that two closely related Hebridean rulers, Ragnall and Rögnvaldr, shared the same personal names,[68][note 11] the same grandfather, and (at times) the same title, has perplexed modern historians and possibly mediaeval chroniclers as well.[68]

Conquest in Caithness

.png)

In the late 12th century, Haraldr Maddaðarson (d. 1206) set his sights on the Scottish earldom of Ross, and associated himself with the meic Áedha, a kindred who were in open rebellion against the King of Scots. To keep Haraldr in check, William launched the first of two expeditions into Haraldr's mainland territory in 1196, with one reaching deep into Caithness. According to John of Fordun (d. after 1363), William's first military action subdued Caithness and Sutherland.[69] The Orkneyinga saga records that Rögnvaldr was tasked by William to intervene on his behalf, and that Rögnvaldr duly gathered an armed host from the Isles, Kintyre, and Ireland, and went into Caithness and subdued the region.[70] The Chronica of Roger of Howden (d. 1201/2) also records William's conflict with Harald, and appears to confirm Rögnvaldr's participation in the region, since it states that a certain "Reginaldus" bought the earldom from the Scottish king.[71] The precise date of Rögnvaldr's venture is uncertain, although it appears to date to about 1200.[72]

Although most scholars have regarded Rögnvaldr to have been the sea-king who assisted the Scottish king against Haraldr, there is evidence which may indicate that it was actually Ragnall who assisted William.[73] For example, the saga makes the erroneous statement that Rögnvaldr was a son of Ingibjörg,[74][note 12] a woman who was much more likely to have been Ragnall's maternal-grandmother than Rögnvaldr's.[75] Also, the saga notes that the king's military force was partly gathered from Kintyre, which may be more likely of Ragnall than Rögnvaldr, since Ragnall is known to have specifically styled himself dominus Ergile et Kyntyre.[76] Also, until recently transcriptions of Howden's account of the episode have stated that the king was in fact a son of Somairle. However, a recent reanalysis of the main extant version of Howden's chronicle has shown that part of the text which originally read "Reginaldus filius rex de Man" was actually altered to include Somairle's name above the last three words. Since the source of the original manuscript likely read "Reginaldus filius Godredi", the sea-king in question appears to have been Rögnvaldr.[77]

Scandinavian sojourn

There is another instance where an historical source records a man who could refer to either Ragnall or Rögnvaldr. The early 13th century Böglunga sögur indicate at one point that men of two Norwegian factions decided to launch a raiding expedition into the Isles. One version of these sagas state that Rögnvaldr (styled "King of Mann and the Isles") and Guðrøðr (styled "King on Mann") had not paid their taxes due to the Norwegian kings; in consequence, the Isles were ravaged until the two travelled to Norway and reconciled themselves with Ingi Bárðarson, King of Norway (d. 1217), whereupon the two took their lands from Ingi as fiefs.[78]

The aforementioned kings of Böglunga sögur likely refer to Rögnvaldr and his son, Guðrøðr (d. 1231),[79] although it has also been suggested that the sagas' 'Rögnvaldr' may instead refer to Ragnall, and that the 'Guðrøðr' of the sagas may actually refer to Rögnvaldr, since the latter's father was named Guðrøðr.[80] The events depicted in the sagas appear to show that, in the wake of destructive Norwegian activity in the Isles, which may have been some sort of officially sanctioned punishment from Scandinavia, Rögnvaldr and his son (or possibly Ragnall and Rögnvaldr) travelled to Norway where they rendered homage to the Norwegian king, and made compensation for unpaid taxes.[81]

Muchdanach and Murchad

According to the 17th century History of the MacDonalds, during Ragnall's tenure his followers fought and slew a certain "Muchdanach", ruler of Moidart and Ardnamurchan, and thus acquired his lands.[82] This ruler may be identical to a certain Murchad, described by the Chronicle of Mann as a man whose "power and energy" were felt throughout the Kingdom of the Isles, and stated by the chronicle to have been killed in 1188, the year of Rögnvaldr's accession to the kingship.[83] The chronicle's brief account of Murchad reveals that he was a member of the kingdom's élite, but whether or not his killing was connected to Rögnvaldr's accession is unknown.[84] If Muchdanach and Murcahd were indeed the same individual, the History of the MacDonalds appears to preserve the memory of meic Somairle intrusion into Garmoran, and may be an example of the feuding between the meic Somairle and Crovan dynasty.[85]

Ecclesiastical activities

.png)

Iona Abbey and the Diocese of Argyll

In the 6th century, exiled-Irishman Colum Cille (d. 527) seated himself on Iona, from where he oversaw the foundation of numerous daughter-houses in the surrounding islands and mainland. Men of his own choosing, many from his own extended family, were appointed to administrate these dependent houses. In time, a lasting monastic network—a ecclesiastical familia—was centred on the island, and led by his successors. During the ongoing Viking onslaught in the 9th century, the leadership of the familia relocated to Kells.[86] In the 12th century, Flaithbertach Ua Brolcháin, Abbot of Derry (d. 1175), the comarba ("successor") of Colum Cille, relocated from Kells to Derry.[87][note 13] In 1164, at a time when Somairle ruled the entire Kingdom of the Isles, the Annals of Ulster indicates that he attempted to reinstate the monastic familia on Iona under Flaithbertach's leadership.[88] Unfortunately for Somairle, the proposal was met with significant opposition, and with his death in the same year, his intentions of controlling the kingdom, diocese, and leadership of the familia came to nothing.[89]

Decades prior to Somairle's seizure of the kingdom, his father-in-law Óláfr founded the Diocese of the Isles by granting the monks of the Savigniac abbey of St Mary of Furness the right of episcopal election, and endowing the English abbey with lands to establish a daughter-house on Mann. By the mid 12th century, at about the time of Óláfr's death and his son's accession, this diocese became encompassed with the Norwegian Archdiocese of Nidaros. Although a significant proportion of the Óláfr's former kingdom eventually fell under control of the meic Somairle, there is no evidence that the administration of the diocese was altered. That being said, the right of patronage appears to have been contested between the meic Somairle and their cousins of the Crovan dynasty.[90] In the early 1190s, Christian, Bishop of the Isles, an Argyllman who was likely a meic Somairle candidate, was deposed and replaced by Michael (d. 1203), a Manxman who appears to have been backed by Ragnall's cousin, Rögnvaldr.[91]

_(crop).jpg)

About forty years after Somairle's death, a Benedictine monastery was established on Iona. The monastery's foundation charter dates to December 1203,[92] which suggests that Ragnall may have been responsible for its erection, as claimed by early modern tradition preserved in the 18th century Book of Clanranald.[93] Be that as it may, since the charter reveals that the monastery received substantial endowments from throughout the meic Somairle domain, the foundation appears to have concerned other leading members the kindred as well.[94] The charter placed the monastery under the protection of Pope Innocent III (d. 1216), which secured it's episcopal independence from the Diocese of the Isles.[95] However, the price for the privilege of Iona's papal protection appears to have been the adoption of the Benedictine Rule, and the supersession of the centuries-old institution of Colum Cille.[96]

The decision of the meic Somairle to establish the Benedictines on Iona completely contrasted the ecclesiastical actions of Somairle himself, and provoked a prompt and violent response from Colum Cille's familia.[87] According to the Annals of Ulster, after Cellach, Abbot of Iona built the new monastery in 1204, a large force of Irishmen, led by the Bishops of Tyrone and Tirconell and the Abbots of Derry and Inishowen, made landfall on Iona and burnt the new buildings to the ground.[97] The sentiments of the familia may well be preserved in a contemporary poem which portrays Colum Cille lamenting the violation of his rights, and cursing the meic Somairle.[98][note 14] Unfortunately for the familia, the Benedictine presence on Iona was there to stay,[99] and the old monastery of Colum Cille was nearly obliterated by the new monastery.[100][note 15]

Sometime in the early 13th century, after the foundation of the Benedictine monastery, an Augustinian nunnery was established just south of the site. As with the abbey, Ragnall was likely responsible for its foundation, and his sister Bethóc was its first prioress.[101] The oldest intact building on the island is St Oran's chapel. Judging from certain Irish influences in its architecture, the chapel is thought to date to about the mid 12th century. The building is known to have been used as a mortuary house by Ragnall's later descendants, and it is possible that either he or his father were responsible for its erection.[102][note 16] Either Dubgall or Ragnall were likely instrumental in the creation of the Diocese of Argyll, probably between 1183 and 1193.[103] The resurgence of the Crovan dynasty during Rögnvaldr's reign may have led to the dioceses' formation,[104] and it may be significant that Ragnall appears to have abandoned the title "King of the Isles" at about this period.[90] The diocese's jurisdiction lay outwith the domain of Rögnvaldr's control, and allowed the meic Somairle to readily act as religious patrons without his interference.[104] In fact, its formation may well have had William's assent, and appears to have formed part of a plan to project Scottish royal authority into the region.[105] Although the early diocese suffered from prolonged vacancies, as only two bishops are recorded to have occupied the see before 1250,[104] over time it became firmly established on the mainland, with its cathedral nearby on Lismore,[106] in the heartland of Dubgall's descendants, the meic Dubgaill.[104]

Saddell Abbey

Either Ragnall or his father could have founded Saddell Abbey,[107] a rather small Cistercian house, situated in the traditional heartland of the meic Somairle.[108] This, now ruinous monastery, is the only Cisterian house known to have been founded in the West Highlands.[109] Surviving evidence from the monastery itself suggests that Ragnall was likely the founder.[110] For example, when the monastery's charters were confirmed in 1393 by Pope Clement VII (d. 1534), and in 1498 and 1508 by James IV, King of Scots (d. 1513), the earliest grant produced by the house was that of Ragnall. Furthermore, the confirmations of 1393 and 1508 specifically state that Ragnall was indeed the founder, as does clan tradition preserved in the Book of Clanranald. However, evidence that Somairle was the founder may be preserved in a 13th-century French list of Cistercian houses which names a certain "Sconedale" under the year 1160.[111]

One possibility is that, while Somairle may well have began the planning a Cistercian house at Saddell, it was actually Ragnall who provided it with its first endowments.[112] However, Somairle's attempt to relocate Colum Cille's familia to Iona, during an era when Cistercians were already established in the Isles,[113] may be evidence that Somairle was something of an "ecclesiastical traditionalist",[114] who found newer reformed orders of continental Christianity unpalatable. In contrast, the ecclesiastical activities of his immediate descendants, particularly the foundations and endowments of Ragnall himself, reveal that the meic Somairle were not adverse to such orders.[113] During his career, Somairle waged war upon the Scots and perished in an invasion of Scotland proper, which could suggest that Ragnall's ecclesiastical activities were partly undertaken to improve relations with the King of Scots.[115] Additionally, in an age when monasteries were often built by rulers as status symbols of their wealth and power, the foundations and endowments of Ragnall may have been undertaken as a means to portray himself as an up-to-date ruler.[116]

Death

The year and circumstances of Ragnall's death are uncertain, as surviving contemporary sources failed to mark his demise.[117] According to clan tradition preserved in the Book of Clanranald, Ragnall may have died in 1207.[118] However, no corroborating evidence supports this date, and there is reason to believe that dates in this source are unreliable.[119] In fact, this source misplaces Somairle's death by sixteen years, which may indicate that Ragnall himself died some sixteen years earlier (in 1191). If this date is correct then Ragnall's death may be related to his defeat suffered at the hands of brother.[120] However, the Chronicle of Mann, which records the 1192 conflict between Ragnall and Áengus, gives no hint of Ragnall's demise in its account.[121] Another possibility is that Ragnall may have been slain sometime around 1209 and 1210, during yet more internal conflict amongst the meic Somairle.[122]

A reanalysis of the Book of Clanranald has shown that, instead of 1207, this source may actually date Ragnall's demise to 1227.[123][note 17] However, this date may well be too late for man who was an adult by 1164.[123] Ragnall's grant to Paisley may leave clues to his fate. The fact that his charter to the priory was likely granted at about the same time as a similar one granted by his son, Domnall, may be evidence that Ragnall was not killed in his defeat against Áengus.[124][note 18] Also, Ragnall's charter may indicate that he entered into a confraternity with the monks there. If this charter was indeed granted near the end of his life, then Ragnall may have ended his days at the priory. Since the prior of Paisley was not one of the religious houses founded by the meic Somairle, his possible retirement there may partly explain why Ragnall disappears from record after 1192.[117]

Family and legacy

"Fonia", the name of Ragnall's wife recorded in their grant to the priory of Paisley, may be an attempt to represent a Gaelic name in Latin.[125] According to late Hebridean tradition, preserved in the garbled History of the MacDonalds, Ragnall was married to "MacRandel's daughter, or, as some say, to a sister of Thomas Randel, Earl of Murray".[126] This tradition cannot be correct due to its chronology,[127] since Thomas Randolph, the first Earl of Moray, and his like-named son and successor, both died in 1332.[128] However, one possibility is that the tradition may instead refer to an earlier earl—Uilleam mac Donnchada (d. between 1151–1154). If this is correct, then Ragnall's son, Domnall, may have been named after Uilleam's son, Domnall (d. 1187),[127] a leading member of the meic Uilleim, a kindred who were in open rebellion against the Kings of Scots from the late 12th- to early 13th centuries.[129]

Ragnall is known to have left two sons: Domnall and Ruaidrí. Domnall's line, the meic Domnaill (or Clann Domnaill), went on to produce the powerful Lords of the Isles, who dominated the entire Hebrides and expansive mainland-territories from the first half of the 14th century to the late 15th century.[130] Ruaidrí founded the meic Ruaidrí, a more obscure kindred who were seated in Garmoran.[131][note 19]

.jpg)

It is very likely that either Ragnall or Ruaidrí had daughters who married Rögnvaldr and his younger half-brother, Óláfr Guðrøðarson.[132] The Chronicle of Mann states that Rögnvaldr had Óláfr marry Lauon, the daughter of a certain nobleman from Kintyre, who was also the sister of his own (unnamed) wife.[133] The precise identification of this nobleman father-in-law is uncertain, although what is known is that both Ragnall and Ruaidrí were contemporaneously styled "Lord of Kintyre". It is possible that Óláfr's marriage took place in the 1220s, and that Rögnvaldr may have orchestrated the marriages in an attempt to patch up relations between the meic Somairle and his own kindred. At about this time, Ruaidrí appears to have been forced from Kintyre by Scottish forces—an act which may have been connected to such an alliance.[132] Unfortunately for Rögnvaldr, Óláfr had his marriage nullified, and later forged a marriage alliance of his own choosing, with a Scottish magnate closely associated with reigning King of Scots. Óláfr eventually forced Rögnvaldr from the kingship, took his place as king, and finally slew Rögnvaldr in 1229.[134]

Ragnall is chiefly remembered in early modern Hebridean tradition as the father of Domnall, as a genealogical link from Somairle to Domnall and his descendants.[135] Unsupported claims made by the Book of Clanranald present Ragnall as "the most distinguished of the Gall or Gaedhil for prosperity, sway of generosity, and feats of arms", and report that he "received a cross from Jerusalem".[136] The latter statement may imply that Ragnall undertook (or planned to undertake) a pilgrimage or crusade. Although Ragnall's involvement in such an enterprise is not impossible, the claim is uncorroborated by contemporary sources.[137] Donald Monro's 1549 description of the Hebrides and the Islands of the Clyde reveals that Ragnall's reign was still remembered in the Isles during the 16th century, when Monro credited him with establishing the law code administered by leading Hebrideans hundreds of years after Ragnall's floruit.[138][note 20]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Ragnall mac Somairle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ The site was greatly restored in the 20th century. The majority of the 'old' church dates to the 15th century. Only the church's choir and the north transept date to the 13th century.[16]

- ↑ The church's design has been mostly unaltered since its construction in the early 13th century, and gives an approximate impression of how the 13th century abbey church would have looked.[20]

- ↑ This Mediaeval Gaelic name means "Ragnall son of Somairle". Scholars have rendered Ragnall's name variously in recent secondary sources: Raghnall,[1] Ragnall,[2] Ranald,[3] Raonall,[4] Raonull,[5] Reginald,[6] and Rögnvaldr.[7] Likewise, his father's name is rendered: Somairle, Somerled, Somhairle, Somhairlidh, and Sumarliði.

- ↑ Another son, Gilla Brigte, who was killed with Somairle in 1164, was likely the product of an earlier marriage.[10] Other than being recorded as a son of Somairle and his wife in the Chronicle of Mann, nothing further is known of Amlaíb.[11]

- ↑ There has been much confusion over the identity of father of Somairle's nephews, and some modern scholars have regarded him as a member of the meic Áeda kindred. Recently, however, Máel Coluim has been identified as an illegitimate son of Alexander I, King of Scots (d. 1124). In the early 12th century, this Máel Coluim is recorded in open rebellion against his uncle David I, King of Scots (d. 1153). At some point prior to his capture and imprisonment by the Scots, Máel Coluim appears to have conducted a marriage alliance with Somairle's father.[9]

- ↑ At a later date this priory was elevated to the status of an abbey.[13]

- ↑ Only about thirty years previous, Ragnall's father had perished whilst launching an attack on Renfrew, the heart of the lordship of Alan's father.[12]

- ↑ The illustration appears in Angus MacDonald and Archibald MacDonald's The Clan Donald, volume 1, which was published in 1896.

- ↑ At the same time of this later charter, Ragnall's son Domnall granted a similar charter to the priory. This may mean that Ragnall was near the end of this life.[14]

- ↑ Although, the Chronicle of Mann records that Eógan mac Donnchada, King in the Isles (d. in or after 1268), styled himself as such in 1250, during his failed invasion of Mann with Magnús Óláfsson (d. 1265). Eógan was a grandson of Ragnall's brother Dubgall. Magnús was a nephew of Rögnvaldr, a member of the Crovan dynasty, and a later King of Mann and the Isles.

- ↑ The Mediaeval Gaelic Ragnall is derived from the Old Norse Rögnvaldr. The names are ultimately cognates of the Latin Reginaldus.

- ↑ Joseph Anderson's 1874 version of the saga reads that Rögnvaldr's father was the son of Ingibjörg. Finnbogi Guðmundsson's 1965 version, and Hermann Pálsson and Paul Geoffrey Edwards' 1978 version, read that Rögnvaldr was the son of Ingibjörg.

- ↑ As head of the familia, Flaithbertach was styled comarba Coluim Chille.[15]

- ↑ Part of the poem has Colum Cille cursing Somairle's descendants: "I will flatten Clann Somhairlidh, both beasts and men, because they'll go from my counsel, I will lay them down in weakness".[18] Ragnall may well have thought differently of his relationship with Colum Cille, since he invoked the wrath of the saint in his grant to the priory of Paisley, cursing anyone who harmed the monks or monastery: "with the certain knowledge that, by St Columba, whosoever of my heirs molests them shall have my malediction, for if peradventure any evil should be done to them or theirs by my people, or by any others whom it is in my power to bring to account, they shall suffer the punishment of death".[19]

- ↑ Hostilities between the meic Somairle and the familia may have continued for decades, as the Annals of Ulster records that Ragnall's (unnamed) sons raided Derry and Inishowen in 1212.[17]

- ↑ It is also possible that St Oran's chapel was erected by members of the Crovan dynasty: either Somairle's brother-in-law Guðrøðr, who was buried on the island in 1188, or Guðrøðr's father (and Somarile's father-in-law) Óláfr.[21]

- ↑ The reasoning is that an ampersand may have been confused as a number.[23]

- ↑ Domnall's charter to the priory is the only contemporary source in which he is named.[22]

- ↑ Several sources, such as the Book of Ballymote and the MS 1467, claim that Ragnall was actually the father of Dubgall (rather than a brother). The author of the MS 1467, who was almost certainly in the employ of the meic Domnaill, may have set the precedent of disparaging accounts of the meic Dubgaill origins by later clan historians. For example, the History of the MacDonalds gives a denigratory account of Dubgall, and claims that he was an illegitimate son of Somairle.[26]

- ↑ Part of Munro's account, which describes how the council convened on Eilean na Comhairle ("council island"), states: "Thir 14 persons sat down into the Councell-Ile and decernit, decreitit and gave suits furth upon all debaitable matters according to the Laws made be Renald McSomharkle callit in his time King of the Occident Iles ...".[24] Similarities between the fourteen-man council named by Munro, and the list of the signatories of the 'Ellencarne' commission, drawn up on Islay in 1545, may be evidence that Munro's description pertains to the mid 16th century, rather than to the 15th century Lordship of the Isles.[25]

- ↑ There are numerous pedigrees outlining the patrilineal ancestry of Clann Domnaill, the descendants of Ragnall's son Domnall. Although these pedigrees take the family's line several generations further back than Gilla Adamnáin, the successive names become more unusual, and the pedigrees begin to contradict each other. Consequently, Gilla Adamnáin may be the furthest the patrilineal line can be taken back with confidence.[28]

References

- Footnotes

- ↑ MacGregor 2000.

- ↑ Beuermann 2010. See also: McDonald 2007. See also: Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005. See also: Woolf 2004.

- ↑ Sellar 2004. See also: Sellar 2000. See also: McDonald 1997.

- ↑ Murray 2005. See also: McDonald 1995a.

- ↑ Barrow 1992.

- ↑ Power 2005. See also: Raven 2005. See also: Cowan 2000. See also: Power 1994. See also: Barrow 1992.

- ↑ Williams 2007.

- ↑ McDonald 2007: p. 25.

- ↑ Oram 2011: pp. 70–72, 111–112.

- ↑ Sellar 2004.

- ↑ Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 197.

- ↑ Murray 2005: p. 288.

- ↑ Barrow 2004b.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 200. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 74 fn 19. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 198 fn 8.

- ↑ Bannerman 1993.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Cross; Livingstone 1997: p. 843. See also Ritchie 1997: pp. 103–108.

- ↑ Beuermann 2012: p. 9. See also: Sellar 2000: p. 200.

- ↑ Clancy 1997: p. 25. See also: Meyor 1918: p. 393.

- ↑ Hammond 2010: pp. 83–84. See also: McDonald 2005: p. 196. See also: Innes 1832: p. 125.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ritchie 1997: pp. 108–110.

- ↑ Power 2005: p. 28.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 200.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 196 fn 41.

- ↑ Cathcart 2012: p. 260. See also: Coira 2012: p. 57. See also: Sellar 2000: pp. 195–196. See also: Munro 1993: p. 57.

- ↑ Cathcart 2012: p. 260.

- ↑ MacGregor 2000: p. 145, 145 fn 91.

- ↑ Black, Ronnie; Black, Máire, MacDonald – tracing the MacDonald genealogy back to Adam (number 35 on the map – 1vd, lines 1–57), (www.1467manuscript.co.uk), retrieved 12 January 2012

- ↑ Woolf 2005.

- ↑ Munch; Goss 1874a: pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Sellar 2004. See also: Sellar 2000: p. 195.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 199, p. 199 fn 51 See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 197.

- ↑ Woolf 2004: p. 103.

- ↑ Oram 2011: p. 111–112. See also: Sellar 2004. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Sellar 2004. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 196. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 230–232. See also: Munch; Goss 1874a: pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Sellar 2004. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 196. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 239. See also: Munch; Goss 1874a: pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Sellar 2004. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 197. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 253–258. See also: Munch; Goss 1874a: pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Sellar 2004. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 197. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 471–472. See also: Munch; Goss 1874a: pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 195.

- ↑ Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 198.

- ↑ Oram 2011: p. 156. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 197.

- ↑ Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: pp. 197–198. See also: Lawrie 1910: p. 204. See also: See also: Anderson 1908: p. 264.

- ↑ Oram 2011: p. 156.

- ↑ Oram 2011: p. 157. See also: Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: p. 247. See also: McDonald 1997: pp. 74–75. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 198. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 327.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Woolf 2004: p. 105.

- ↑ McDonald 2005: pp. 195–196. See also: McDonald 1995c: pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: pp. 246–248. See also: Murray 2005: p. 288.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: p. 243.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: pp. 247.

- ↑ Oram 2011: p. 157. See also: Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: pp. 247. See also: Murray 2005: p. 288.

- ↑ Oram 2011: p. 157. See also: Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: pp. 246–248. See also: Murray 2005: p. 288.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 75. See also: McDonald 1995a: pp. 131–132. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 198 fn 7.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 195. See also: Barrow 1992: p. 25 fn 9. See also: Paul 1882: p. 678 (#3170).

- ↑ Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 198.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 195.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 74. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 198, 198 fn 8.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 195. See also: Innes 1832: p. 125.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 195 fn 37.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 74. See also: McDonald 1995a: p. 135. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 198.

- ↑ Munro; Munro 2004. See also: Sellar 2000: p. 195 fn 37. See also: McDonald 1997: pp. 2, 187.

- ↑ McDonald 1995a: p. 129.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 75. See also: McDonald 1995a: p. 130. See also: Innes 1832: p. 149.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 198.

- ↑ McDonald 2005: pp. 192–193 fn 49. See also: Sellar 2000: p. 198. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 75. See also: McDonald 1995a: p. 131.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 75–76. See also: McDonald 1995a: p. 135–136, 142.

- ↑ McDonald 2005: pp. 192–193 fn 49. See also: McDonald 1995a: pp. 133, 142.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Williams 2007: pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Crawford 2004a.

- ↑ Williams 2007: pp. 146–148. See also: Crawford 2004a. See also: Sellar 2000: pp. 196–197. See also: Anderson 1873: pp. 195–196.

- ↑ McDonald 2007: pp. 110–110. See also: Williams 2007: p. 147. See also: Crawford 2004a. See also: Sellar 2000: pp. 196–197. See also: Barrow 1992: p. 83 fn 65. See also: Anderson 1908: pp. 316–318. See also: Stubbs 1871: p. 12.

- ↑ McDonald 2007: p. 110.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: pp. 196–197.

- ↑ McDonald 2007: p. 72.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: pp. 196–198.

- ↑ Williams 2007: pp. 146–148. See also: Paul 1882: p. 678 (#3170). See also: Anderson 1873: pp. 195–196.

- ↑ Beuermann 2008. See also: McDonald 2007: p. 110.

- ↑ Beuermann 2010: p. 106. See also: McDonald 2007: p. 134. See also: Johnsen 1969: p. 23. See also: Finnur Magnússon; Rafn 1835: p. 194.

- ↑ Beuermann 2011: p. 125. See also: Beuermann 2010: p. 106 fn 19–20. See also: McDonald 2007: p. 134. See also: See also: Johnsen 1969: p. 23.

- ↑ McDonald 2007: p. 134 fn 61. See also: Power 2005: p. 39. See also: Cowan 1990: pp. 112, 114.

- ↑ McDonald 2007: p. 135. See also: Power 2005: p. 39.

- ↑ Raven 2005: p. 58. See also: MacPhail 1914: pp. 12, 17.

- ↑ McDonald 2007: pp. 38, 169. See also: Raven 2005: p. 58. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 314.

- ↑ McDonald 2007: p. 169.

- ↑ Raven 2005: p. 58.

- ↑ Herbert 2004.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 Power 2005: p. 29.

- ↑ Power 2005: pp. 28–29. See also: Woolf 2004: p. 106. See also: Thornton 2004. See also: Bambury; Beechinor; Hennessy; et al. 2000: 1164.2. See also: Ó Corráin; Cournane; Hennessy; et al. 2000: 1164.2.

- ↑ Beuermann 2012: p. 5. See also: Power 2005: pp. 28–29. See also: Woolf 2004: p. 106.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Watts 1994: pp. 111–114.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 210. See also: Watts 1994: pp. 111–114.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 218–219. See also: Munch; Goss 1874b: pp. 285–288.

- ↑ Power 2005: p. 29. See also: McDonald 1997: pp. 218–219. See also: Macbain; Kennedy 1894: pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Power 2005: p. 29. See also: Munch; Goss 1874b: pp. 285–288.

- ↑ Beuermann 2012: p. 6. See also: Power 2005: pp. 29–30. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 218–219. See also: Watts 1994: p. 113 fn 7. See also: Munch; Goss 1874b: pp. 285–288.

- ↑ Beuermann 2012: p. 6.

- ↑ Beuermann 2012: p. 9. See also: Power 2005: p. 29. See also: Bambury; Beechinor; Hennessy; et al. 2003: 1204.4. See also: Ó Corráin; Cournane; Hennessy; et al. 2003: 1204.4.

- ↑ Hammond 2010: p. 83. See also: Márkus 2007: pp. 98–99. See also: Clancy 1997: p. 25.

- ↑ Bannerman 1993: p. 46.

- ↑ Power 2005: p. 30.

- ↑ Power 2005: p. 30–31. See also: McDonald 1995: pp. 208–209. See also: Ritchie 1997: pp. 108–110.

- ↑ Power 2005: p. 28. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 246. See also Ritchie 1997: pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 203. See also: McDonald 1997: pp. 211–213. See also: Barrow 1992: p. 79 fn 49. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 209.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 104.3 McDonald 1997: pp. 211–213.

- ↑ Barrow 1992: p. 79.

- ↑ Woolf 2004: p. 106. See also: McDonald 1997: pp. 211–213.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 203. See also: Brown 1969: pp. 130–133.

- ↑ Power 2005: p. 31.

- ↑ McDonald 1995c: p. 209.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 203. See also: Brown 1969: pp. 130–133.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 220. See also: Brown 1969: p. 132. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 247. See also: Birch 1870: p. 361.

- ↑ Brown 1969: p. 132.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 McDonald 1997: p. 221. See also: McDonald 1995c: pp. 210–213.

- ↑ Beuermann 2012: p. 2.

- ↑ McDonald 1995c: p. 216.

- ↑ McDonald 1995c: pp. 215–216.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 McDonald 1997: p. 79.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 196. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 78. See also: Macbain; Kennedy 1894: p. 157.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 196, 196 fn 41.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 196. See also: McDonald 1997: pp. 78–79. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 198 fn 5.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 79.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 79. See also: Cowan 1990: pp. 112, 114.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Sellar 2000: p. 196, 196 fn 41. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 79.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 196.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 195. See also: Innes 1832: p. 125.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 200. See also: MacPhail 1914: p. 13.

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 Sellar 2000: p. 200.

- ↑ Duncan 2004b.

- ↑ Scott 2004. See also: Sellar 2000: p. 200.

- ↑ Munro; Munro 2004.

- ↑ McDonald 2005: p. 181.

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 McDonald 2007: pp. 116–117, 152. See also: Raven 2005: pp. 57–58. See also Woolf 2004: p. 107.

- ↑ McDonald 2007: pp. 116–117. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 256–260.

- ↑ McDonald 2007: pp. 152–156.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 195.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 196. See also: McDonald 1997: pp. 77–78. See also: Macbain; Kennedy 1894: pp. 156–157.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Coira 2012: p. 57. See also: Sellar 2000: pp. 195–196.

- Primary sources

- Anderson, Alan Orr, ed. (1908), Scottish annals from English chroniclers, a.d. 500 to 1286, David Nutt.

- Anderson, Alan Orr, ed. (1922), Early sources of Scottish history: a.d. 500 to 1286 2, Oliver and Boyd.

- Anderson, Joseph, ed. (1873), The Orkneyinga saga, translated by Jón Andrésson Hjaltalín and Gilbert Goudie, Edmonston and Douglas.

- Bambury, Pádraig; Beechinor, Stephen; Hennessy, William M.; Mac Carthy, Bartholomew; Mac Airt, Seán; Mac Niocaill, Gearóid, eds. (2000), The annals of Ulster ad 431–1201 (15 August 2012 ed.), CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Bambury, Pádraig; Beechinor, Stephen; Hennessy, William M. et al., eds. (2003), The Annals of ulster ad 1202–1378 (28 January 2003 ed.), CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, retrieved 18 February 2013 .

- Birch, Walter de Gray (1870), "On the date of foundation ascribed to Cistertian abbeys of Great Britain", The Journal of the British Archaeological Association (British Archaeological Association) 26: 281–299, 352–369.

- Innes, Cosmo, ed. (1832), Registrum monasterii de Passelet, Maitland Club.

- Lawrie, Archibald Campbell, ed. (1910), Annals of the reigns of Malcolm and William, kings of Scotland, a.d. 1153–1214, James MacLehose and Sons.

- Macbain, Alexander; Kennedy, John, eds. (1894), "The Book of Clanranald", Reliquiæ Celticæ: texts, papers and studies in Gaelic literature and philology 2, The Northern Counties Newspaper and Printing and Publishing Company, pp. 138–309.

- MacPhail, James Robert Nicolson, ed. (1914), Highland papers 1, Scottish History Society.

- Magnússon, Finnur; Rafn, Carl Christian, eds. (1835), Fornmanna sögur 9.

- Meyer, Kuno (1918), "Mitteilungen aus irischen handschriften (fortsetzung)", Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 12: 358–397.

- Munro, R. W., ed. (1993) [1961], Munro's Western Isles of Scotland and genealogies of the clans: 1549, Genealogical Publishing Company, ISBN 0-8063-5076-8.

- Munch, Peter Andreas; Goss, Alexander, eds. (1874a), Chronica regvm Manniæ et Insvlarvm: the chronicle of Man and the Sudreys; from the manuscript codex in the British Museum; with historical notes 1, printed for the Manx Society.

- Munch, Peter Andreas; Goss, Alexander, eds. (1874b), Chronica regvm Manniæ et Insvlarvm: the chronicle of Man and the Sudreys; from the manuscript codex in the British Museum; with historical notes 2, printed for the Manx Society.

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh; Cournane, Mavis; Hennessy, William M. et al., eds. (2003), The annals of Ulster ad 1202–1378 (13 April 2005 ed.), CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, retrieved 18 February 2013 .

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh; Cournane, Mavis; Hennessy, William M.; Mac Carthy, Bartholomew; Mac Airt, Seán; Mac Niocaill, Gearóid, eds. (2008), The annals of Ulster ad 431–1201 (29 August 2008 ed.), CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Paul, James Balfour, ed. (1882), Registrum magni sigilli regum Scotorum: the register of the great seal of Scotland, a.d. 1424-1513, HM General Register House.

- Stubbs, William, ed. (1871), Chronica magistri Rogeri de Houedene 4, Longman and Company; Trübner and Company.

- Secondary sources

- Bannerman, John (1993), "Comarba Coluim Chille and the relics of Columba", The Innes Review 44 (1): 14–47.

- Barrow, Geoffrey Wallis Steuart (1992), Scotland and its neighbours in the middle ages, Hambledon Press, ISBN 1 85285 052 3. – via Google Books

- Barrow, Geoffrey Wallis Steuart (2004), "Stewart family (per. c.1110–c.1350), nobility", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49411, retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Beuermann, Ian (2008), "New British history focusing on the Isle of Man", H-Net Reviews (H-Albion), retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Beuermann, Ian (2010), "'Norgesveldet?' south of Cape Wrath?", in Imsen, Steinar, The Norwegian domination and the Norse world c. 1100–c. 1400, Norgesveldt Occasional Papers (Trondheim Studies in History), Tapir Academic Press, pp. 99–123, ISBN 978-82-519-2563-1.

- Beuermann, Ian (2011), "Jarla Sǫgur Orkneyja. Status and power of the earls of Orkney according to their sagas", in Steinsland, Gro; Sigurðsson, Jón Viðar; Rekdal, Jan Erik et al., Ideology and power in the viking and middle ages: Scandinavia, Iceland, Ireland, Orkney and the Faeroes, The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 A.D. Peoples, Economics and Cultures 52, Brill, pp. 109–161, ISBN 978-90-04-20506-2 .

- Beuermann, Ian (2012), "The Norwegian attack on Iona in 1209–10: the last viking raid?" (pdf), Iona Research Conference (www.ionahistory.org.uk), retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Brown, A. L. (1969), "The Cistercian abbey of Saddell, Kintyre", The Innes Review 20: 130–137, doi:10.3366/inr.1969.20.2.130, ISSN 0020-157X.

- Cathcart, Alison (2012), "The forgotten '45: Donald Dubh's rebellion in an archipelagic context", Scottish Historical Review 91: 239–264, doi:10.3366/shr.2012.0101, ISSN 0036-9241.

- Clancy, Thomas Owen (1997), "Columba, Adomnán and the cult of saints in Scotland", The Innes Review, 1 48: 1–26, doi:10.3366/inr.1997.48.1.1, ISSN 0020-157X.

- Coira, M. Pía (2012), By poetic authority: the rhetoric of panegyric in Gaelic poetry of Scotland to c.1700, Dunedin Academic Press. – via Questia (subscription required)

- Corner, David (2004), "Howden [Hoveden], Roger of (d. 1201/2), chronicler", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13880, retrieved 30 October 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Cowan, Edward J. (1990), "Norwegian sunset — Scottish dawn: Hakon IV and Alexander III", in Reid, Norman H., Scotland in the reign of Alexander III, 1249–1286, John Donald, pp. 103–131, ISBN 0-85976-218-1.

- Crawford, Barbara Elizabeth (2004a), "Harald Maddadson [Haraldr Maddaðarson], earl of Caithness and earl of Orkney (1133/4–1206), magnate", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49351, retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (1997), The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211655-X.

- Duncan, Archibald Alexander McBeth; Brown, A. L. (1956–1957), "Argyll and the Isles in the earlier middle ages" (pdf), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (Society of Antiquaries of Scotland) 90: 192–220 .

- Duncan, Archibald Alexander McBeth (2004a), "Duncan II (b. before 1072, d. 1094), king of Scots", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49370, retrieved 12 October 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Duncan, Archibald Alexander McBeth (2004b), "Randolph, Thomas, first earl of Moray (d. 1332)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54305, retrieved 12 October 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard D.; Pedersen, Frederik (2005), Viking empires, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Hammond, Mathew H. (2010), "Royal and aristocratic attitudes to saints and the Virgin Mary in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Scotland", in Boardman, Steve; Williamson, Eila, The cult of saints and the Virgin Mary in medieval Scotland, Studies in Celtic History, Boydell & Brewer, pp. 61–87, ISBN 978-1-84383-562-2.

- Herbert, Máire (2004), "Columba [St Columba, Colum Cille] (c.521–597), monastic founder", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6001, retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Johnsen, Arne Odd (1969), "The payments from the Hebrides and Isle of Man to the crown of Norway 1153–1263: annual ferme or feudal casualty?", The Scottish Historical Review (Edinburgh University Press) 48 (145, part 1): 18–64, JSTOR 25528786.

- MacGregor, Martin (2000), "Genealogies of the clans: contributions to the study of the MS 1467", The Innes Review 51: 131–146, doi:10.3366/inr.2000.51.2.131, ISSN 0020-157X.

- McDonald, Russell Andrew (1995a), "Images of Hebridean lordship in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries: the seal of Raonall Mac Sorley", The Scottish Historical Review (Edinburgh University Press) 74 (198): 129–143, JSTOR 25530679.

- McDonald, Russell Andrew (1995b), "Matrimonial politics and core-periphery interaction in twelfth- and early thirteenth-century Scotland", Journal of Medieval History 21: 227–247.

- McDonald, Russell Andrew (1995c), "Scoto-Norse kings and the reformed religious orders: patterns of monastic patronage in twelfth-century Galloway and Argyll", Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies (The North American Conference on British Studies) 27 (2): 187–219, JSTOR 4051525.

- McDonald, Russell Andrew (1997), The kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's western seaboard, c.1100–c.1336, Scottish Historical Monographs, Tuckwell Press, ISBN 978-1-898410-85-0.

- McDonald, Russell Andrew (2005), "Coming in from the margins: the descendants of Somerled and cultural accommodation in the Hebrides, 1164–1317", in Smith, Brendan, Britain and Ireland, 900–1300: insular responses to medieval European change, Cambridge University Press, pp. 179–198, ISBN 0-511-03855-0.

- McDonald, Russell Andrew (2007), Manx kingship in its Irish sea setting, 1187–1229: king Rǫgnvaldr and the Crovan dynasty, Four Courts Press, ISBN 978-1-84682-047-2.

- Munro, R. W.; Munro, Jean (2004), "MacDonald family [MacDhomnaill, MacDonald de Ile] (per. c.1300–c.1500), magnates", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54280, retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Murray, Noel (2005), "Swerving from the path of justice: Alexander II's relations with Argyll and the Western Isles, 1214–1249", in Oram, Richard D., The reign of Alexander II, 1214–49, Brill, pp. 285–305, ISBN 978-90-04-14206-0, ISSN 1569-1462.

- Márkus, Gilbert (2007), "Saving verse: early medieval religious poetry", in Brown, Ian; Clancy, Thomas Owen; Manning, Susan et al., The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature, Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature 1, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 91–102, ISBN 978-0-7486-2862-9 .

- Oram, Richard D. (2011), Domination and lordship: Scotland 1070–1230, The new Edinburgh history of Scotland, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978 0 7486 1496 7. via Google Books and Questia (subscription required)

- Power, Rosemary (2005), "Meeting in Norway: Norse-Gaelic relations in the kingdom of Man and the Isles, 1090–1270" (pdf), Saga-Book (Viking Society for Northern Research) 29: 5–66, ISSN 0305-9219.

- Raven, John A. (2005), Medieval landscapes and lordship in South Uist (Ph.D. thesis) 1, University of Glasgow.

- Ritchie, Anna (1997), Iona, B T Batsford, ISBN 0 7134 7855 1.

- Scott, W. W. (2004), "Macwilliam family (per. c.1130–c.1230)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49357, retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Sellar, William David Hamilton (2000), "Hebridean sea kings: The successors of Somerled, 1164–1316", in Cowan, Edward J.; McDonald, Russell Andrew, Alba: Celtic Scotland in the middle ages, Tuckwell Press, pp. 187–218, ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Sellar, William David Hamilton (2004), "Somerled (d. 1164), king of the Hebrides and regulus of Argyll and Kintyre", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26782, retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Thornton, David E. (2004), "Ua Brolcháin, Flaithbertach (d. 1175), abbot of Derry and head of Columban churches in Ireland", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20472, retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Watt, Donald Elmslie Robertson (1994), "Bishops in the Isles before 1203: bibliography and biographical lists", The Innes Review 45 (2): 99–119.

- Williams, Gareth (2007), "'These people were high-born and thought a lot of themselves': a family of Moddan of Dale", in Smith, Beverley Ballin; Taylor, Simon; Williams, Gareth, West over the sea: studies in Scandinavian sea-borne expansion and settlement before 1300, The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economies and Cultures 31, Brill, pp. 129–152, ISBN 978-90-04-15893-1, ISSN 1569-1462.

- Woolf, Alex (2004), "The age of sea-kings, 900–1300", in Omand, Donald, The Argyll book, Birlinn, pp. 94–109, ISBN 1-84158-253-0.

- Woolf, Alex (2005), "The origins and ancestry of Somerled: Gofraid mac Fergusa and 'The Annals of the Four Masters'", Mediaeval Scandinavia 15: 199–213.

External links

- Reginald (Ragnvald), lord of Argyll @ People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314

- Fonia, wife of Rognvald lord of Isles @ People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)