Radical Pietism

Radical Pietism refers to a movement within Protestantism, lasting from the late 17th century to the mid 18th century and later, which emphasized the need for a "religion of the heart" instead of the head, and was characterized by ethical purity, inward devotion, charity, asceticism, and even mysticism. Leadership was empathetic to adherents instead of being strident loyalists to sacramentalism. Many of the Radical Pietists were influenced by the writings of Jakob Böhme, Gottfried Arnold, and Philipp Jakob Spener, among others.

The Pietistic movement was birthed in Germany through spiritual pioneers who wanted a deeper emotional experience rather than a preset adherence to form (no matter how genuine). They stressed a personal experience of salvation and a continuous openness to new spiritual illumination.

They also taught that personal holiness (piety), spiritual maturity, Bible study, prayer, and fasting were essential towards "feeling the effects" of grace.

As a movement, Pietism influenced individuals who chose to remain within their denominational settings (usually referred to as Church Pietists), as well as those who decided to break with their established churches and form other groups. The latter were known as Radical Pietists. These distinguished between true and false Christianity (usually represented by established churches), which led to their separation from these entities.[1]

Communitarian living

A common trait among radical Pietists, is that they formed communities where they sought to revive the original Christian living of the Acts of the Apostles.

Jean de Labadie (1610–1674) founded a communitarian group in Europe which was known, after its founder, as the Labadists. Johannes Kelpius (1673–1708) led a communitarian group who came to America from Germany in 1694. Conrad Beissel (1691–1768), founder of another early pietistic communitarian group, the Ephrata Cloister, was also particularly affected by Radical Pietism's emphasis on personal experience and separation from false Christianity. The Harmony Society (1785–1906), founded by George Rapp, was another German-American religious group influenced by Radical Pietism. Other groups include the Zoarite Separatists (1817–1898), and the Amana Colonies (1855-today).

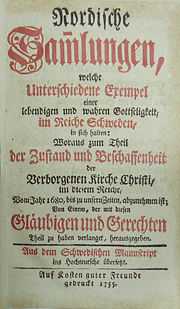

In Sweden, a group of radical pietists formed a community, the "Skevikare", on an island outside of Stockholm, where they lived much like the Ephrata people, for nearly a century.[2]

Radical Pietism's role in the emergence of modern religious communities has only begun to be adequately assessed, according to Hans Schneider, professor of church history at the University of Marburg, Germany.[3]

Endtime expectations, breakdown of social barriers

Two other common traits of radical Pietism were their strong endtime expectations, and their breakdown of social barriers. They were very influenced by prophecies gathered and published by John Amos Comenius and Gottfried Arnold. Events like comets and lunar eclipses were seen as signs of threatening divine judgements. In Pennsylvania, Johannes Kelpius even installed a telescope on the roof of his house, where he and his followers kept watch for heavenly signs proclaiming the return of Christ.

As for the social barriers, in Germany and Sweden the familiar pronomen "thou" ("du") was commonly used among the radical Pietists. They also strongly abandoned class designation and academic degrees. The barriers between men and women were also broken down. Many radical pietistic women became wellknown as writers and prophets, as well as leaders of Philadelphian communities.[4]

See also

- Pietism

- Asceticism

- Behmenism

- Johann Conrad Dippel

- Jean de Labadie

- Labadists

- Johannes Kelpius

- Schwarzenau Brethren

- Conrad Beissel

- Amana Colonies

- George Rapp

- Harmony Society

- Templers (religious believers)

- Radical Christianity

References

- ↑ Ronald J. Gordon: Rise of Pietism in 17th Century Germany. Located at: http://www.cob-net.org/pietism.htm

- ↑ Alfred Kämpe, "Främlingarna på Skevik" (1924)

- ↑ German Radical Pietism, by Hans Schneider

- ↑ German Radical Pietism/The Roots, Origin, and Terminology of Radical Pietism

Bibliography

Books and articles in German:

- Hans-Jürgen Schrader: Literaturproduktion und Büchermarkt des radikalen Pietismus: Johann Heinrich Reitz' "Historie der Wiedergebohrnen" und ihr geschichtlicher Kontext (Palaestra 283). Göttingen 1989.

- Ulf-Michael Schneider: Propheten der Goethezeit. Sprache, Literatur und Wirkung der Inspirierten (Palaestra 297). Göttingen 1995.

- Barbara Hoffmann: Radikalpietismus um 1700. Der Streit um das Recht auf eine neue Gesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main 1996.

- Andreas Deppermann: Johann Jakob Schütz und die Anfänge des Pietismus. Tübingen 2002.

- Willi Temme: Krise der Leiblichkeit. Die Sozietät der Mutter Eva (Buttlarsche Rotte) und der radikale Pietismus um 1700 (Arbeiten zur Geschichte des Pietismus 35). Göttingen 1998.

- Johannes Burkardt/Michael Knieriem: Die Gesellschaft der Kindheit-Jesu-Genossen auf Schloss Hayn. Aus dem Nachlass des von Fleischbein und Korrespondenzen von de Marsay, Prueschenk von Lindenhofen und Tersteegen 1734 bis 1742. Hannover 2002.

- Eberhard Fritz: Radikaler Pietismus in Württemberg. Religiöse Ideale im Konflikt mit gesellschaftlichen Realitäten (Quellen und Forschungen zur württembergischen Kirchengeschichte 18). Epfendorf 2003.

- Eberhard Fritz: Separatistinnen und Separatisten in Württemberg und in angrenzenden Territorien. Ein biographisches Verzeichnis (Südwestdeutsche Quellen zur Familienforschung Band 3). Stuttgart 2005.

- Hans Schneider: Radical German Pietism. Translated by Gerald MacDonald. Lanham, MD 2007.

- Douglas H. Shantz: Between Sardis and Philadelphia: the Life and World of Pietist Court Preacher Conrad Bröske. Leiden 2008.