R-value (insulation)

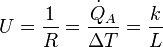

The R-value is a measure of thermal resistance[1] used in the building and construction industry. Under uniform conditions it is the ratio of the temperature difference across an insulator and the heat flux (heat transfer per unit area per unit time,  ) through it or

) through it or  . The R-value being discussed is the unit thermal resistance. This is used for a unit value of any particular material. It is expressed as the thickness of the material divided by the thermal conductivity. For the thermal resistance of an entire section of material, instead of the unit resistance, divide the unit thermal resistance by the area of the material. For example, if you have the unit thermal resistance of a wall, divide it by the cross-sectional area of the depth of the wall to compute the thermal resistance. The unit thermal conductance of a material is denoted as C and is the reciprocal of the unit thermal resistance. This can also be called the unit surface conductance, commonly denoted by h.[2] The higher the number, the better the building insulation's effectiveness. R-value is the reciprocal of U-factor.

. The R-value being discussed is the unit thermal resistance. This is used for a unit value of any particular material. It is expressed as the thickness of the material divided by the thermal conductivity. For the thermal resistance of an entire section of material, instead of the unit resistance, divide the unit thermal resistance by the area of the material. For example, if you have the unit thermal resistance of a wall, divide it by the cross-sectional area of the depth of the wall to compute the thermal resistance. The unit thermal conductance of a material is denoted as C and is the reciprocal of the unit thermal resistance. This can also be called the unit surface conductance, commonly denoted by h.[2] The higher the number, the better the building insulation's effectiveness. R-value is the reciprocal of U-factor.

U-factor/U-Value

The U-factor or "U-value", is the overall heat transfer coefficient that describes how well a building element conducts heat or the rate of transfer of heat (in watts) through one square metre of a structure divided by the difference in temperature across the structure. The elements are commonly assemblies of many layers of components such as those that make up walls/floors/roofs etc. It measures the rate of heat transfer through a building element over a given area under standardised conditions. The usual standard is at a temperature gradient of 24 °C (75 °F), at 50% humidity with no wind[3] (a smaller U-factor is better at reducing heat transfer). It is expressed in watts per metres squared kelvin, or W/m²K. This means that the higher the U value the worse the thermal performance of the building envelope. A low U value usually indicates high levels of insulation. They are useful as it is a way of predicting the composite behaviour of an entire building element rather than relying on the properties of individual materials.

In much of the world the properties of specific materials (such as insulation) are indicated by the k-value or lambda-value (lowercase λ) of an insulant. The k-value is the ability of a material to conduct heat (thermal conductivity); hence, The lower the K-value, the better the material is for insulation. Expanded Polystyrene (EPS), has a K-value of around 0.033 W/m2K[4]. For comparison, Phenolic foam insulation has a K-value of around 0.018 W/m2K[5], while wood varies anywhere from 0.15- 0.75 and steel has a K-Value of approximately 50.0. These figures vary from product to product, so the UK & EU have established a 90/90 standard which means that 90% of the product will conform to the stated k value with a 90% confidence level so long as the figure quoted is stated as the 90/90 lambda value.

U is the inverse of R with SI units of W/(m2K) and US units of BTU/(h °F ft2);

where k is the material's thermal conductivity and L is its thickness.

See also: tog (unit) or Thermal Overall Grade (where 1 tog = 0.1 m2·K/W), used for duvet rating.

Note that the phrase "U-Factor" (which redirects here) is used in the US to express the insulation value of windows only,[6] R-value is used for insulation in most other parts of the building envelope (walls, floors, roofs). Other areas of the world generally use U-Value/U-Factor for elements of the entire building envelope: including windows, doors, walls, roof & ground slabs.

Internationally

Around most of the world, R-values are given in SI units, typically square-metre kelvin per watt or m2·K/W (or equally, m2·°C/W). In the United States customary units, R-values are given in units of ft2·°F·hr/Btu. It is particularly easy to confuse SI and US R-values, because R-values both in the US and elsewhere are often cited without their units, e.g., R-3.5. Usually, however, the correct units can be inferred from the context and from the magnitudes of the values. United States R-values are approximately six times SI R-values.

Heat transfer through an insulating layer is analogous to electrical resistance. The heat transfers can be worked out by thinking of resistance in series with a fixed potential, except the resistances are thermal resistances and the potential is the difference in temperature from one side of the material to the other. The resistance of each material to heat transfer depends on the specific thermal resistance [R-value]/[unit thickness], which is a property of the material (see table below) and the thickness of that layer. A thermal barrier that is composed of several layers will have several thermal resistors in the analogous circuit, each in series. Like resistance in electrical circuits, increasing the physical length of a resistive element (graphite, for example) increases the resistance linearly; double the thickness of a layer means half the heat transfer and double the R-value; quadruple, quarters; etc. In practice, this linear relationship does not hold for compressible materials such as glass wool batting whose thermal properties change when compressed.

Different insulation types

The US Department of Energy has recommended R-values for given areas of the USA based on the general local energy costs for heating and cooling, as well as the climate of an area. There are four types of insulation: rolls and batts, loose-fill, rigid foam, and foam-in-place. Rolls and batts are typically flexible insulators that come in fibers, like fiberglass. Loose-fill insulation comes in loose fibers or pellets and should be blown into a space. Rigid foam is more expensive than fiber, but generally has a higher R-value per unit of thickness. Foam-in-place insulation can be blown into small areas to control air leaks, like those around windows, or can be used to insulate an entire house.[7]

Thickness

Increasing the thickness of an insulating layer increases the thermal resistance. For example, doubling the thickness of fiberglass batting will double its R-value, perhaps from 2.0 m2K/W for 110 mm of thickness, up to 4.0 m2K/W for 220 mm of thickness. Heat transfer through an insulating layer is analogous to adding resistance to a series circuit with a fixed voltage. However, this only holds approximately because the effective thermal conductivity of some insulating materials depends on thickness. The addition of materials to enclose the insulation such as sheetrock and siding provides additional but typically much smaller R-value.

Factors

There are many factors that come into play when using R-values to compute heat loss for a particular wall. Manufacturer R values apply only to properly installed insulation. Squashing two layers of batting into the thickness intended for one layer will increase but not double the R-value. (In other words, compressing a fiberglass batt decreases the R-value of the batt but increases the R-value per inch.) Another important factor to consider is that studs and windows provide a parallel heat conduction path that is unaffected by the insulation's R-value. The practical implication of this is that one could double the R-value of insulation installed between framing members and realize substantially less than a 50% reduction in heat loss. When installed between wall studs, even perfect wall insulation only eliminates conduction through the insulation but leaves unaffected the conductive heat loss through such materials as glass windows and studs. Insulation installed between the studs may reduce, but usually does not eliminate, heat losses due to air leakage through the building envelope. Installing a continuous layer of rigid foam insulation on the exterior side of the wall sheathing will interrupt thermal bridging through the studs while also reducing the rate of air leakage.

Primary role

The R-value is a measure of an insulation sample's ability to reduce the rate of heat flow under specified test conditions. The primary mode of heat transfer impeded by insulation is conduction, but insulation also reduces heat loss by all three heat transfer modes: conduction, convection, and radiation. The primary means of heat loss across an uninsulated air-filled space is natural convection, which occurs because of changes in air density with temperature. Insulation greatly retards natural convection making the primary mode of heat transfer conduction. Porous insulations accomplish this by trapping air so that significant convective heat loss is eliminated, leaving only conduction and minor radiation transfer. The primary role of such insulation is to make the thermal conductivity of the insulation that of trapped, stagnant air. However this cannot be realized fully because the glass wool or foam needed to prevent convection increases the heat conduction compared to that of still air. The minor radiative heat transfer is minimized by having many surfaces interrupting a "clear view" between the inner and outer surfaces of the insulation much as visible light is interrupted from passing through porous materials. Such multiple surfaces are abundant in batting and porous foam. Radiation is also minimized by low emissivity (highly reflective) exterior surfaces such as aluminum foil. Lower thermal conductivity, or higher R-values, can be achieved by replacing air with argon when practical such as within special closed-pore foam insulation because argon has a lower thermal conductivity than air.

Units

The conversion between SI and US units of R-value is 1 h·ft2·°F/Btu = 0.176110 K·m2/W, or 1 K·m2/W = 5.678263 h·ft2·°F/Btu.[8]

More simply, R-values may be converted from SI to US units through the following, where RSI is the given unit in metric units:

- R-value (US) = RSI × 5.678263337

Or converted from US units to SI units, where R-value is given in imperial units:

- RSI (SI) = R-value × 0.1761101838

To disambiguate between the two, some authors use the abbreviation "RSI" for the SI definition .

Example (SI units)

To find the heat loss per square meter, simply divide the temperature difference by the R value.

If the interior of a home is at 20 °C, and the roof cavity is at 10 °C, the temperature difference is 10 °C (= 10 K difference). Assuming a ceiling insulated to R–2 (R = 2.0 m2K/W), energy will be lost at a rate of 10 K/2 K·m2/W = 5 watts for every square meter of ceiling.

Relationships

Thickness

R-value should not be confused with the intrinsic property of thermal resistivity and its inverse, thermal conductivity. The SI unit of thermal resistivity is K·m/W. Thermal conductivity assumes that the heat transfer of the material is linearly related to its thickness.

Multiple layers

In calculating the R-value of a multi-layered installation, the R-values of the individual layers are added:[9]

- R-value(outside air film) + R-value(brick) + R-value(sheathing) + R-value(insulation) + R-value(plasterboard) + R-value(inside air film) = R-value(total).

To account for other components in a wall such as framing, an area-weighted average R-value of the whole wall may be calculated.

Controversy

Thermal conductivity versus apparent thermal conductivity

Thermal conductivity is conventionally defined as the rate of thermal conduction through a material per unit area per unit thickness per unit temperature differential (ΔT). The inverse of conductivity is resistivity (or R per unit thickness). Thermal conductance is the rate of heat flux through a unit area at the installed thickness and any given ΔT.

Experimentally, thermal conduction is measured by placing the material in contact between two conducting plates and measuring the energy flux required to maintain a certain temperature gradient.

For the most part, testing the R-value of insulation is done at a steady temperature, usually about 70 °F (21 °C) with no surrounding air movement. Since these are ideal conditions, the listed R-value for insulation will almost certainly be higher than it would be in actual use, because most situations with insulation are under different conditions

A definition of R-value based on apparent thermal conductivity has been proposed in document C168 published by the American Society for Testing and Materials. This describes heat being transferred by all three mechanisms—conduction, radiation, and convection.

Debate remains among representatives from different segments of the U.S. insulation industry during revision of the U.S. FTC's regulations about advertising R-values [10] illustrating the complexity of the issues.

Surface temperature in relationship to mode of heat transfer

There are weaknesses to using a single laboratory model to simultaneously assess the properties of a material to resist conducted, radiated, or convective heating. Surface temperature varies depending on the mode of heat transfer.

In the absence of radiation or convection, the surface temperature of the insulator should equal the air temperature on each side.

In response to thermal radiation, surface temperature depends on the thermal emissivity of the material. Light, reflective, or metallic surfaces that are exposed to radiation tend to maintain lower temperatures than dark, non-metallic ones.

Convection will alter the rate of heat transfer (and surface temperature) of an insulator, depending on the flow characteristics of the gas or fluid in contact with it.

With multiple modes of heat transfer, the final surface temperature (and hence the observed energy flux and calculated R-value) will be dependent on the relative contributions of radiation, conduction, and convection, even though the total energy contribution remains the same.

This is an important consideration in building construction because heat energy arrives in different forms and proportions. The contribution of radiative and conductive heat sources also varies throughout the year and both are important contributors to thermal comfort

In the hot season, solar radiation predominates as the source of heat gain. As radiative heat transfer is related to the cube power of the absolute temperature, such transfer is then at its most significant when the objective is to cool (i.e. when solar radiation has produced very warm surfaces). On the other hand, the conductive and convective heat loss modes play a more significant role during the cooler months. At such lower ambient temperatures the traditional fibrous, plastic and cellulose insulations play by far the major role: the radiative heat transfer component is of far less importance and the main contribution of the radiation barrier is in its superior air-tightness contribution. In summary: claims for radiant barrier insulation are justifiable at high temperatures, typically when minimizing summer heat transfer; but these claims are not justifiable in traditional winter (keeping-warm) conditions.

The limitations of R-values in evaluating radiant barriers

Unlike bulk insulators, radiant barriers resist conducted heat poorly. Materials such as reflective foil have a high thermal conductivity and would function poorly as a conductive insulator. Radiant barriers retard heat transfer by two means - by reflecting radiant energy away from its surface or by reducing the emission of radiation from its opposite side.

The question of how to quantify performance of other systems such as radiant barriers has resulted in controversy and confusion in the building industry with the use of R-values or 'equivalent R-values' for products which have entirely different systems of inhibiting heat transfer. (In the U.S., the federal government's R-Value Rule establishes a legal definition for the R-value of a building material; the term 'equivalent R-value' has no legal definition and is therefore meaningless.) According to current standards, R-values are most reliably stated for bulk insulation materials. All of the products quoted at the end are examples of these.

Calculating the performance of radiant barriers is more complex. With a good radiant barrier in place, most heat flow is by convection, which depends on many factors other than the radiant barrier itself. Although radiant barriers have high reflectivity (and low emissivity) over a range of electromagnetic spectra (including visible and UV light), their thermal advantages are mainly related to their emissivity in the infra-red range. Emissivity values [11] are the appropriate metric for radiant barriers. Their effectiveness when employed to resist heat gain in limited applications is established,[12] even though R-value does not adequately describe them.

Deterioration

Insulation aging

R-values of products may deteriorate over time. For instance the compaction of loose fill cellulose creates voids that reduce overall performance; this may be avoided by densely packing the initial installation. Some types of foam insulation, such as polyurethane and polyisocyanurate are blown with heavy gases such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFC) or hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HFCs). However, over time a small amount of these gases diffuse out of the foam and are replaced by air, thus reducing the effective R-value of the product. There are other foams which do not change significantly with aging because they are blown with water or are open-cell and contain no trapped CFCs or HFCs (e.g., half-pound low density foams). On certain brands, twenty-year tests have shown no shrinkage or reduction in insulating value.[citation needed]

This has led to controversy as how to rate the insulation of these products. Many manufacturers will rate the R-value at the time of manufacture; critics argue that a more fair assessment would be its settled value.[citation needed] The foam industry adopted the LTTR (Long-Term Thermal Resistance) method,[13] which rates the R-value based on a 15 year weighted average. However, the LTTR effectively provides only an eight-year aged R-value, short in the scale of a building that may have a lifespan of 50 to 100 years.

There has been a test method conceived to test the flammability of thermal/acoustic insulation. This type of insulation usually contains a thin film of moisture barrier over a batting material, with the possibility of foam being a second barrier. The test also takes into account small detail parts of the insulation which might contribute to whether or not the insulation is flammable. Such details include thread, tape, and fasteners. The test consists of putting the insulation next to an ignition source, then observing whether or not it catches fire. Then, if the specimen has caught fire, the ignition source is removed and the insulation is observed to see if it continues to burn.[14]

Infiltration

Correct attention to air sealing measures and consideration of vapor transfer mechanisms are important for the optimal function of bulk insulators. Air infiltration can allow convective heat transfer or condensation formation, both of which may degrade the performance of an insulation.

One of the primary values of spray-foam insulation is its ability to create an airtight (and in some cases, watertight) seal directly against the substrate to reduce the undesirable effects of air leakage.

Example values

- Note that these examples use the non-SI definition and/or given for a 1 inch (25.4 mm) thick sample.

Vacuum insulated panels have the highest R-value (approximately R–45 per inch in American customary units); aerogel has the next highest R-value (about R–10-30 per inch), followed by isocyanurate and phenolic foam insulations with, R–8.3 and R–7 per inch, respectively. They are followed closely by polyurethane and polystyrene insulation at roughly R–6 and R–5 per inch. Loose cellulose, fiberglass (both blown and in batts), and rock wool (both blown and in batts) all possess an R-value of roughly R–-2.5 to R–-4 per inch. Straw bales perform at about R–1.5. However, typical straw bale houses have very thick walls and thus are well insulated. Snow is roughly R–1.

Brick has a very poor insulative ability at a mere R–0.2, however it does have a relatively good Thermal mass.

Typical per-unit-thickness R-values for material

| Material | m2·K/(W·in) | ft2·°F·h/(BTU·in) | m·K/W |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vacuum insulated panel | 5.28–8.8 | R-30–R-50 | |

| Silica aerogel | 1.76 | R-10 | |

| Polyurethane rigid panel (CFC/HCFC expanded) initial | 1.23–1.41 | R-7–R-8 | |

| Polyurethane rigid panel (CFC/HCFC expanded) aged 5–10 years | 1.10 | R-6.25 | |

| Polyurethane rigid panel (pentane expanded) initial | 1.20 | R-6.8 | |

| Polyurethane rigid panel (pentane expanded) aged 5–10 years | 0.97 | R-5.5 | |

| Foil faced Polyurethane rigid panel (pentane expanded) | 45-48 [15] | ||

| Foil-faced polyisocyanurate rigid panel (pentane expanded ) initial | 1.20 | R-6.8 | 55 [15] |

| Foil-faced polyisocyanurate rigid panel (pentane expanded) aged 5–10 years | 0.97 | R-5.5 | |

| Polyisocyanurate spray foam | 0.76–1.46 | R-4.3–R-8.3 | |

| Closed-cell polyurethane spray foam | 0.97–1.14 | R-5.5–R-6.5 | |

| Phenolic spray foam | 0.85–1.23 | R-4.8–R-7 | |

| Thinsulate clothing insulation | 1.01 | R-5.75 | |

| Urea-formaldehyde panels | 0.88–1.06 | R-5–R-6 | |

| Urea foam[16] | 0.92 | R-5.25 | |

| Extruded expanded polystyrene (XPS) high-density | 0.88–0.95 | R-5–R-5.4 | 26-40[15] |

| Polystyrene board[16] | 0.88 | R-5.00 | |

| Phenolic rigid panel | 0.70–0.88 | R-4–R-5 | |

| Urea-formaldehyde foam | 0.70–0.81 | R-4–R-4.6 | |

| High-density fiberglass batts | 0.63–0.88 | R-3.6–R-5 | |

| Extruded expanded polystyrene (XPS) low-density | 0.63–0.82 | R-3.6–R-4.7 | |

| Icynene loose-fill (pour fill)[17] | 0.70 | R-4 | |

| Molded expanded polystyrene (EPS) high-density | 0.70 | R-4.2 | 22-32[15] |

| Home Foam[18] | 0.69 | R-3.9 | |

| Rice hulls[19] | 0.50 | R-3.0 | 24 |

| Fiberglass batts[20] | 0.55–0.76 | R-3.1–R-4.3 | |

| Cotton batts (Blue Jean insulation)[21] | 0.65 | R-3.7 | |

| Molded expanded polystyrene (EPS) low-density | 0.65 | R-3.85 | |

| Icynene spray[17] | 0.63 | R-3.6 | |

| Open-cell polyurethane spray foam | 0.63 | R-3.6 | |

| Cardboard | 0.52–0.7 | R-3–R-4 | |

| Rock and slag wool batts | 0.52–0.68 | R-3–R-3.85 | |

| Cellulose loose-fill[22] | 0.52–0.67 | R-3–R-3.8 | |

| Cellulose wet-spray[22] | 0.52–0.67 | R-3–R-3.8 | |

| Rock and slag wool loose-fill[23] | 0.44–0.65 | R-2.5–R-3.7 | |

| Fiberglass loose-fill[23] | 0.44–0.65 | R-2.5–R-3.7 | |

| Polyethylene foam | 0.52 | R-3 | |

| Cementitious foam | 0.35–0.69 | R-2–R-3.9 | |

| Perlite loose-fill | 0.48 | R-2.7 | |

| Wood panels, such as sheathing | 0.44 | R-2.5 | 9 [24] |

| Fiberglass rigid panel | 0.44 | R-2.5 | |

| Vermiculite loose-fill | 0.38–0.42 | R-2.13–R-2.4 | |

| Vermiculite[25] | 0.38 | R-2.13 | 16-17[15] |

| Straw bale[26] | 0.26 | R-1.45 | 16-22[15] |

| Papercrete[27] | R-2.6-R-3.2 | ||

| Softwood (most)[28] | 0.25 | R-1.41 | 7.7 [24] |

| Wood chips and other loose-fill wood products | 0.18 | R-1 | |

| Snow | 0.18 | R-1 | |

| Hardwood (most)[28] | 0.12 | R-0.71 | 5.5 [24] |

| Brick | 0.030 | R-0.2 | 1.3-1.8[24] |

| Glass[16] | 0.025 | R-0.14 | |

| Poured concrete[16] | 0.014 | R-0.08 | 0.43-0.87 [24] |

Typical R-values for surfaces

Non-reflective surface R-values for air films[29]

When determining the overall thermal resistance of a building assembly such as a wall or roof, the insulating effect of the surface air film is added to the thermal resistance of the other materials.

| Surface position | Direction of heat transfer | RUS (hr·ft2·°F/Btu) | RSI (K·m2/W) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal (e.g., a flat ceiling) | Upward (e.g.. winter) | 0.61 | 0.11 |

| Horizontal (e.g., a flat ceiling) | Downward (e.g., summer) | 0.92 | 0.16 |

| Vertical (e.g., a wall) | Horizontal | 0.68 | 0.12 |

| Outdoor surface, any position, moving air 6.7 m/s (winter) | Any direction | 0.17 | 0.030 |

| Outdoor surface, any position, moving air 3.4 m/s (summer) | Any direction | 0.25 | 0.044 |

In practice the above surface values are used for floors, ceilings, and walls in a building, but are not accurate for enclosed air cavities, such as between panes of glass. The effective thermal resistance of an enclosed air cavity is strongly influenced by radiative heat transfer and distance between the two surfaces. See insulated glazing for a comparison of R-values for windows, with some effective R-values that include an air cavity.

Radiant barriers

| Material | Apparent R-Value (Min) | Apparent R-Value (Max) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflective insulation | Zero[30] (For assembly without adjacent air space.) | R-10.7 (heat transfer down), R-6.7 (heat transfer horizontal), R-5 (heat transfer up)

Ask for the R-value tests from the manufacturer for your specific assembly. |

[23][31] |

R-Value Rule in the US

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) governs claims about R-values to protect consumers against deceptive and misleading advertising claims. "The Commission issued the R-Value Rule[32] to prohibit, on an industry-wide basis, specific unfair or deceptive acts or practices." (70 Fed. Reg. at 31,259 (May 31, 2005).)

The primary purpose of the rule, is to ensure the home insulation marketplace to provides this essential pre-purchase information to the consumer. The information gives consumers an opportunity to compare relative insulating efficiencies, to select the product with the greatest efficiency and potential for energy savings, to make a cost-effective purchase and to consider the main variables limiting insulation effectiveness and realization of claimed energy savings.

The rule mandates that specific R-value information for home insulation products be disclosed in certain ads and at the point of sale. The purpose of the R-value disclosure requirement for advertising is to prevent consumers from being misled by certain claims which have a bearing on insulating value. At the point of transaction, some consumers will be able to get the requisite R-value information from the label on the insulation package. However, since the evidence shows that packages are often unavailable for inspection prior to purchase, no labeled information would be available to consumers in many instances. As a result, the Rule requires that a fact sheet be available to consumers for inspection before they make their purchase.

Thickness

The R-value Rule specifies:[33]

In labels, fact sheets, ads, or other promotional materials, do not give the R-value for one inch or the "R-value per inch" of your product. There are two exceptions:

You can list a range of R-value per inch. If you do, you must say exactly how much the R-value drops with greater thickness. You must also add this statement: "The R-value per inch of this insulation varies with thickness. The thicker the insulation, the lower the R-value per inch." |

See also

- Building insulation

- Building insulation materials

- Condensation

- Cool roofs

- Heat transfer

- Passivhaus

- Passive solar design

- Sol-air temperature

- Superinsulation

- Thermal bridge

- Thermal comfort

- Thermal conductivity

- Thermal mass

- Thermal transmittance

- Tog (unit)

References

- ↑ Desjarlais, André O. "Which Kind Of Insulation Is Best?". Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ McQuiston, Parker, Spitler. Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning: Analysis and Design, Sixth Edition. Hoboken NJ: John Wiley and Sons Inc., 2005.

- ↑ P2000 Insulation System, R-value Testing

- ↑ Polystyrene insulation

- ↑ European phenolic foam association: Properties of phenolic foam

- ↑ "Efficient Windows Collaborative".

- ↑ “Insulation”. U.S. Department of Energy. USA.gov. October 2010. 14 November 2010. <http://www.energysavers.gov/tips/insulation.cfm>

- ↑ 2009 ASHRAE Handbook - Fundamentals (I-P Edition). (pp: 38.1). American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc

- ↑ http://www.ornl.gov/sci/roofs+walls/insulation/ins_02.html

- ↑ R-Value Rule Review

- ↑ http://www.electro-optical.com/bb_rad/emissivity/matlemisivty.htm#Metals%20and%20Conversion%20Coatings

- ↑ FSEC-CR-1231-01-ES

- ↑ "Thermal resistance and polyiso insulation" by John Clinton, Professional Roofing magazine, February 2002

- ↑ United States. Federal Aviation Administration. Thermal/Acoustic Insulation Flame Propagation Test Method Details. Washington, D.C. : U.S. Dept. of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, 2005.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Energy Saving Trust. "CE71 - Insulation materials chart – thermal properties and environmental ratings".

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Ristinen, Robert A., and Jack J. Kraushaar. Energy and the Environment. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Icynene product information

- ↑ Home Foam (manufactured by Elastochem Specialty Chemicals) Product Specifications

- ↑ Rice Hull Insulation

- ↑ Fiberglass Batts R Value Information

- ↑ Environmental Home Center Cotton Batt Information

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 ICC Legacy Report ER-2833 - Cocoon Thermal and Sound Insulation Products, ICC Evaluation Services, Inc., http://www.icc-es.org

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 DOE Handbook.Link text

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Brian Anderson (2006). "Conventions for U-value calculations".

- ↑ http://www.e-star.com/ecalcs/table_rvalues.html e-star data

- ↑ http://www.buildinggreen.com/auth/article.cfm?fileName=070902b.xml

- ↑ http://www.masongreenstar.com/sites/default/files/Research_Report_Thermal_17p.pdf

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 http://www.energysavers.gov/your_home/designing_remodeling/index.cfm/mytopic=10170

- ↑ 2009 ASHRAE Handbook - Fundamentals (I-P Edition & SI Edition). (pp: 26.1). American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc

- ↑ FTC Letter, Regarding reflective insulation used under slab where no air space is present

- ↑ ICC ES Report, ICC ES Report ESR-1236 Thermal and Moisture Protection - ICC Evaluation Services, Inc.

- ↑ Labeling and Advertising of Home Insulation (R-Value Rule) 16 CFR 460 (Federal Trade Commission, USA)

- ↑ http://ecfr.gpoaccess.gov/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ecfr&sid=cb66a61ae5c0b2a136f438291a8f6cd3&rgn=div5&view=text&node=16:1.0.1.4.58&idno=16

External links

- Information on the calculations, meanings, and inter-relationships of related heat transfer and resistance terms

- American building material R-value table

- Working with R-values

- Tables of R-values

Calculations

- R-Value Table, ColoradoENERGY.org (US Imperial units)