Quantum vortex

In physics, a quantum vortex is a topological defect exhibited in superfluids and superconductors. The existence of these quantum vortices was predicted by Lars Onsager in 1947 in connection with superfluid helium. Onsager also pointed out that quantum vortices describe circulation of superfluid and conjectured that their excitations are responsible for superfluid phase transition. These ideas of Onsager were further developed by Richard Feynman in 1955 [1] and in 1957 were applied to describe magnetic phase diagram of type-II superconductors by Alexei Alexeyevich Abrikosov[2] in the 1950s.

Quantum vortices are observed experimentally in Type-II superconductors, liquid helium, and atomic gases (see Bose-Einstein condensate).

In a superfluid, a quantum vortex "carries" quantized angular momentum, thus allowing the superfluid to rotate; in a superconductor, the vortex carries quantized magnetic flux.

Vortex in a superfluid

In a superfluid, a quantum vortex is a hole with the superfluid circulating around the vortex; the inside of the vortex may contain excited particles, air, vacuum, etc. The thickness of the vortex depends on a variety of factors; in liquid helium, the thickness is of the order of a few Angstroms.

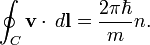

A superfluid has the special property of having phase, given by the wavefunction, and the velocity of the superfluid is proportional to the gradient of the phase. The circulation around any closed loop in the superfluid is zero, if the region enclosed is simply connected. The superfluid is deemed irrotational. However, if the enclosed region actually contains a smaller region that is an absence of superfluid, for example a rod through the superfluid or a vortex, then the circulation is,

where  is Planck's constant divided by

is Planck's constant divided by  , m is the mass of the superfluid particle, and

, m is the mass of the superfluid particle, and  is the phase difference around the vortex. Because the wavefunction must return to its same value after an integral number of turns around the vortex (similar to what is described in the Bohr model), then

is the phase difference around the vortex. Because the wavefunction must return to its same value after an integral number of turns around the vortex (similar to what is described in the Bohr model), then  , where n is an integer. Thus, we find that the circulation is quantized:

, where n is an integer. Thus, we find that the circulation is quantized:

Vortex in a superconductor

A principal property of superconductors is that they expel magnetic fields; this is called the Meissner effect. If the magnetic field becomes sufficiently strong, one scenario is for the superconductive state to be "quenched". However, in some cases, it may be energetically favorable for the superconductor to form a lattice of quantum vortices, which carry quantized magnetic flux through the superconductor. A superconductor that is capable of having vortex lattices is called a type-II superconductor.

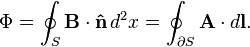

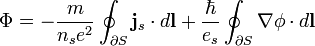

Over some enclosed area S, the magnetic flux is

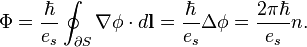

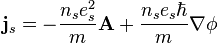

Substituting a result of London's equation:  , we find

, we find

,

,

where ns, m, and es are the number density, mass and charge of the Cooper pairs.

If the region, S, is large enough so that  along

along  , then

, then

The flow of current can cause vortices in a superconductor to move, it causes the electric field due to the phenomenon of electromagnetic induction. This leads to energy dissipation and causes the material to display a small amount of electrical resistance while in the superconducting state.[3]

Statistical mechanics of vortex lines

As first discussed by Onsager and Feynman, If the temperature is raised in a superfluid or a superconductor, the vortex loops undergo a second-order phase transition. This happens when the configurational entropy overcomes the Boltzmann factor which suppresses the thermal or heat generation of vortex lines. The lines form a condensate. Since the center of the lines, the vortex cores, are normal liquid or normal conductors, respectively, the condensation transforms the superfluid or superconductor into the normal state. The ensembles of vortex lines and their phase transitions can be described efficiently by a gauge theory.

See also

- Macroscopic quantum phenomena

- Vortex

- Abrikosov vortex

- Josephson vortex

- Fractional vortices

- Superfluid helium-4

- Superfluid film

- Superconductor

- Type-II superconductor

- Type-1.5 superconductor

- Quantum turbulence

- Bose-Einstein condensate

References

- ↑ Feynman, R. P. (1955). "Application of quantum mechanics to liquid helium". Progress in Low Temperature Physics. Progress in Low Temperature Physics 1: 17–53. doi:10.1016/S0079-6417(08)60077-3. ISBN 978-0-444-53307-4.

- ↑

- Abrikosov, A. A. (1957) "On the Magnetic properties of superconductors of the second group", Sov.Phys.JETP 5:1174-1182 and Zh.Eksp.Teor.Fiz.32:1442-1452.

- ↑ "First vortex 'chains' observed in engineered superconductor". Physorg.com. Retrieved 2011-03-23.