Quantum operation

In quantum mechanics, a quantum operation (also known as quantum dynamical map or quantum process) is a mathematical formalism used to describe a broad class of transformations that a quantum mechanical system can undergo. This was first discussed as a general stochastic transformation for a density matrix by George Sudarshan.[1] The quantum operation formalism describes not only unitary time evolution or symmetry transformations of isolated systems, but also the effects of measurement and transient interactions with an environment. In the context of quantum computation, a quantum operation is called a quantum channel.

Quantum operations are formulated in terms of the density operator description of a quantum mechanical system. Rigorously, a quantum operation is a linear, completely positive map from the set of density operators into itself.

Some quantum processes cannot be captured within the quantum operation formalism;[2] in principle, the density matrix of a quantum system can undergo completely arbitrary time evolution. Quantum operations are generalized by quantum instruments, which capture the classical information obtainined during measurements, in addition to the quantum information.

Background

The Schrödinger picture provides a satisfactory account of time evolution of state for a quantum mechanical system under certain assumptions. These assumptions include

- The system is non-relativistic

- The system is isolated.

The Schrödinger picture for time evolution has several mathematically equivalent formulations. One such formulation expresses the time rate of change of the state via the Schrödinger equation. A more suitable formulation for this exposition is expressed as follows:

- The effect of the passage of t units of time on the state of an isolated system S is given by a unitary operator Ut on the Hilbert space H associated to S.

This means that if the system is in a state corresponding to v ∈ H at an instant of time s, then the state after t units of time will be Ut v. For relativistic systems, there is no universal time parameter, but we can still formulate the effect of certain reversible transformations on the quantum mechanical system. For instance, state transformations relating observers in different frames of reference are given by unitary transformations. In any case, these state transformations carry pure states into pure states; this is often formulated by saying that in this idealized framework, there is no decoherence.

For interacting (or open) systems, such as those undergoing measurement, the situation is entirely different. To begin with, the state changes experienced by such systems cannot be accounted for exclusively by a transformation on the set of pure states (that is, those associated to vectors of norm 1 in H). After such an interaction, a system in a pure state φ may no longer be in the pure state φ. In general it will be in a statistical mix of a sequence of pure states φ1,..., φk with respective probabilities λ1,..., λk. The transition from a pure state to a mixed state is known as decoherence.

Numerous mathematical formalisms have been established to handle the case of an interacting system. The quantum operation formalism emerged around 1983 from work of Karl Kraus, who relied on the earlier mathematical work of Man-Duen Choi. It has the advantage that it expresses operations such as measurement as a mapping from density states to density states. In particular, the effect of quantum operations stays within the set of density states.

Definition

Recall that a density operator is a non-negative operator on a Hilbert space with unit trace.

Mathematically, a quantum operation is a linear map Φ between spaces of trace class operators on Hilbert spaces H and G such that

- If S is a density operator, Tr(Φ(S)) ≤ 1.

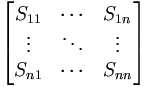

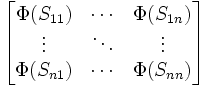

- Φ is completely positive, that is for any natural number n, and any square matrix of size n whose entries are trace-class operators

and which is non-negative, then

is also non-negative. In other words, Φ is completely positive if  is positive for all n, where

is positive for all n, where  denotes the identity map on the C*-algebra of

denotes the identity map on the C*-algebra of  matrices.

matrices.

Note that, by the first condition, quantum operations may not preserve the normalization property of statistical ensembles. In probabilistic terms, quantum operations may be sub-Markovian. In order that a quantum operation preserve the set of density matrices, we need the additional assumption that it is trace-preserving.

In the context of quantum information, the quantum operations defined here, i.e. completely positive maps that do not increase the trace, are also called quantum channels or stochastic maps. The formulation here is confined to channels between quantum states; however, it can be extended to include classical states as well, therefore allowing quantum and classical information to be handled simultaneously.

Kraus operators

Kraus' theorem characterizes maps that model quantum operations between density operators of quantum state:

Theorem.[3] Let H and G be Hilbert spaces of dimension n and m respectively, and Φ be a quantum operation taking the density matrices acting on H to those acting on G. Then there are matrices

mapping G to H, such that

Conversely, any map Φ of this form is a quantum operation provided

The matrices  are called Kraus operators. (Sometimes they are known as noise operators or error operators, especially in the context quantum information processing where the quantum operation represents the noisy, error-producing effects of the environment.) The Stinespring factorization theorem extends the above result to arbitrary separable Hilbert spaces H and G. There, S is replaced by a trace class operator and

are called Kraus operators. (Sometimes they are known as noise operators or error operators, especially in the context quantum information processing where the quantum operation represents the noisy, error-producing effects of the environment.) The Stinespring factorization theorem extends the above result to arbitrary separable Hilbert spaces H and G. There, S is replaced by a trace class operator and  by a sequence of bounded operators.

by a sequence of bounded operators.

Unitary equivalence

Kraus matrices are not uniquely determined by the quantum operation Φ in general. For example, different Cholesky factorizations of the Choi matrix might give different sets of Kraus operators. The following theorem states that all systems of Kraus matrices which represent the same quantum operation are related by a unitary transformation:

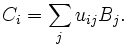

Theorem. Let Φ be a (not necessarily trace preserving) quantum operation on a finite dimensional Hilbert space H with two representing sequences of Kraus matrices {Bi}i≤ N and {Ci}i≤ N . Then there is a unitary operator matrix  such that

such that

In the infinite dimensional case, this generalizes to a relationship between two minimal Stinespring representations.

It is a consequence of Stinespring's theorem that all quantum operations can be implemented via unitary evolution after coupling a suitable ancilla to the original system.

Remarks

These results can be also derived from Choi's theorem on completely positive maps, characterizing a completely positive finite-dimensional map by a unique Hermitian-positive density operator (Choi matrix) with respect to the trace. Among all possible Kraus representations of a given channel, there exists a canonical form

distinguished by the orthogonality relation of Kraus operators,  . Such a canonical set of orthogonal Kraus operators can be obtained by diagonalising the corresponding Choi matrix and reshaping its eigenvectors into square matrices.

. Such a canonical set of orthogonal Kraus operators can be obtained by diagonalising the corresponding Choi matrix and reshaping its eigenvectors into square matrices.

There also exists an infinite dimensional algebraic generalization of Choi's theorem, known as 'Belavkin's Radon-Nikodym theorem for completely positive maps', which defines a density operator as a "Radon-Nikodym derivative" of a quantum channel with respect to a dominating completely positive map (reference channel). It is used for defining the relative fidelities and mutual informations for quantum channels.

Dynamics

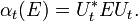

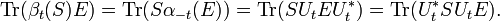

For a non-relativistic quantum mechanical system, its time evolution is described by a one-parameter group of automorphisms {αt}t of Q. This can be narrowed to unitary transformations: under certain weak technical conditions (see the article on quantum logic and the Varadarajan reference), there is a strongly continuous one-parameter group {Ut}t of unitary transformations of the underlying Hilbert space such that the elements E of Q evolve according to the formula

The system time evolution can also be regarded dually as time evolution of the statistical state space. The evolution of the statistical state is given by a family of operators {βt}t such that

Clearly, for each value of t, S → U*t S Ut is a quantum operation. Moreover, this operation is reversible.

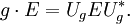

This can be easily generalized: If G is a connected Lie group of symmetries of Q satisfying the same weak continuity conditions, then the action of any element g of G is given by a unitary operator U:

This mapping g → Ug is known as a projective representation of G. The mappings S → U*g S Ug are reversible quantum operations.

Quantum measurement

Quantum operations can be used to describe the process of quantum measurement. The presentation below describes measurement in terms of self-adjoint projections on a separable complex Hilbert space H, that is, in terms of a PVM. In the general case, measurements can be made using non-orthogonal operators, via the notions of POVM. The non-orthogonal case is interesting, as it can improve the overall efficiency of the quantum instrument.

Binary measurements

Quantum systems may be measured by applying a series of yes–no questions. This set of questions can be understood to be chosen from an orthocomplemented lattice Q of propositions in quantum logic. The lattice is equivalent to the space of self-adjoint projections on a separable complex Hilbert space H.

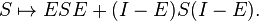

Consider a system in some state S, with the goal of determining whether it has some property E, where E is an element of the lattice of quantum yes-no questions. Measurement, in this context, means submitting the system to some procedure to determine whether the state satisfies the property. The reference to system state, in this discussion, can be given an operational meaning by considering a statistical ensemble of systems. Each measurement yields some definite value 0 or 1; moreover application of the measurement process to the ensemble results in a predictable change of the statistical state. This transformation of the statistical state is given by the quantum operation

Here E can e understood to be a projection operator.

General case

In the general case, measurements are made on observables taking on more than two values.

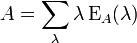

When an observerable A has a pure point spectrum, it can be written in terms of an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors. That is, A has a spectral decomposition

where EA(λ) is a family of pairwise orthogonal projections, each onto the respective eigenspace of A associated with the measurement value λ.

Measurement of the observable A yields an eigenvalue of A. Repeated measurements, made on a statistical ensemble S of systems, results in a probability distribution over the eigenvalue spectrum of A. It is a discrete probability distribution, and is given by

Measurement of the statisical state S is given by the map

That is, immediately after measurement, the statistical state is a classical distribution over the eigenspaces associated with the possible values λ of the observable: S is a mixed state.

Non-completely positive maps

Shaji and Sudarshan argued in a Physics Letters A paper that, upon close examination, complete positivity is not a requirement for a good representation of open quantum evolution. Their calculations show that, when starting with some fixed initial correlations between the observed system and the environment, the map restricted to the system itself is not necessarily even positive. However, it is not positive only for those states that do not satisfy the assumption about the form of initial correlations. Thus, they show that to get a full understanding of quantum evolution, non completely-positive maps should be considered as well.[2][4]

References

- ↑ "Stochastic Dynamics of Quantum-Mechanical Systems" .

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Philip Pechukas, "Reduced Dynamics Need Not Be Completely Positive", Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1060 (1994).

- ↑ This theorem is proved in the Nielsen and Chuang reference, Theorems 8.1 and 8.3.

- ↑ Anil Shaji and E.C.G. Sudarshan "Who's Afraid of not Completely Positive Maps?", Physics Letters A Volume 341, 20 June 2005, Pages 48–54

- M. Nielsen and I. Chuang, Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, Cambridge University Press, 2000

- M. Choi, Completely Positive Linear Maps on Complex matrices, Linear Algebra and Its Applications, 285–290, 1975

- E. C. G. Sudarshan et al. Stochastic Dynamics of Quantum-Mechanical Systems, Phys. Rev. 121, 920–924, 1961.

- V. P. Belavkin, P. Staszewski, Radon–Nikodym Theorem for Completely Positive Maps, Reports on Mathematical Physics, v.24, No 1, 49–55, 1986.

- K. Kraus, States, Effects and Operations: Fundamental Notions of Quantum Theory, Springer Verlag 1983

- W. F. Stinespring, Positive Functions on C*-algebras, Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 211–216, 1955

- V. Varadarajan, The Geometry of Quantum Mechanics vols 1 and 2, Springer-Verlag 1985