Quantum-confined Stark effect

The quantum-confined Stark effect (QCSE) describes the effect of an external electric field upon the light absorption spectrum or emission spectrum of a quantum well (QW). In the absence of an external electric field, electrons and holes within the quantum well may only occupy states within a discrete set of energy subbands. Consequently, only a discrete set of frequencies of light may be absorbed or emitted by the system. When an external electric field is applied, the electron states shift to lower energies, while the hole states shift to higher energies. This reduces the permitted light absorption or emission frequencies. Additionally, the external electric field shifts electrons and holes to opposite sides of the well, decreasing the overlap integral, which in turn reduces the recombination efficiency (i.e. fluorescence quantum yield) of the system. [1] The spatial separation between the electrons and holes is limited by the presence of the potential barriers around the quantum well, meaning that excitons are able to exist in the system even under the influence of an electric field. The quantum-confined Stark effect is used in QCSE optical modulators, which allow optical communications signals to be switched on and off rapidly.

Even if Quantum Objects (Wells, Dots or Discs, for instance) emit and absorb light generally with higher energies than the band gap of the material, the QCSE may shift the energy to values lower than the gap. This was evidenced recently in the study of quantum discs embeded in a nanowire.[2]

Theoretical description

The shift in absorption lines can be calculated by comparing the energy levels in unbiased and biased quantum wells. It is a simpler task to find the energy levels in the unbiased system, due to its symmetry. If the external electric field is small, it can be treated as a perturbation to the unbiased system and its approximate effect can be found using perturbation theory.

Unbiased system

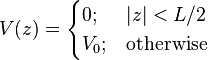

The potential for a quantum well may be written as

,

,

where  is the width of the well and

is the width of the well and  is the height of the potential barriers. The bound states in the well lie at a set of discrete energies,

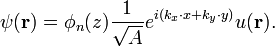

is the height of the potential barriers. The bound states in the well lie at a set of discrete energies,  and the associated wavefunctions can be written using the envelope function approximation as follows:

and the associated wavefunctions can be written using the envelope function approximation as follows:

In this expression,  is the cross-sectional area of the system, perpendicular to the quantisation direction,

is the cross-sectional area of the system, perpendicular to the quantisation direction,  is a periodic Bloch function for the energy band edge in the bulk semiconductor and

is a periodic Bloch function for the energy band edge in the bulk semiconductor and  is a slowly varying envelope function for the system.

is a slowly varying envelope function for the system.

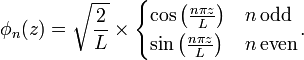

If the quantum well is very deep, it can be approximated by the particle in a box model, in which  . Under this simplified model, analytical expressions for the bound state wavefunctions exist, with the form

. Under this simplified model, analytical expressions for the bound state wavefunctions exist, with the form

The energies of the bound states are

where  is the effective mass of an electron in a given semiconductor.

is the effective mass of an electron in a given semiconductor.

Biased system

Supposing the electric field is biased along the z direction,

the perturbing Hamiltonian term is

The first order correction to the energy levels is zero due to symmetry.

.

.

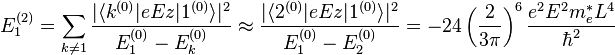

The second order correction is, for instance n=1,

for electrons.

Similar calculations can be applied to holes by replacing the electron effective mass with the hole effective mass.

Absorption coefficient

Addition to energy level shift, the DC electric field causes decrease of absoption coefficient. Because electron and hole are forced to opposite direction by the field, the overlap of relating valence and conduction band in transition is decreased. Thus, according to Fermi's golden rule, which says that transition probability is proportional to the overlap, optical transition strength is weakened. Using this, light absorption of materials can be controlled by changing electric field and can be used as an optical modulator.

References

- ↑ Miller, D. (1984). "Band-Edge Electroabsorption in Quantum Well Structures: The Quantum-Confined Stark Effect". Phys. Rev. Lett. 53: 2173–2176. Bibcode:1984PhRvL..53.2173M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.2173.

- ↑ Zagonel, L. F. (2011). "Nanometer Scale Spectral Imaging of Quantum Emitters in Nanowires and Its Correlation to Their Atomically Resolved Structure". Nano Letters 11: 568–573. arXiv:1209.0953. Bibcode:2011NanoL..11..568Z. doi:10.1021/nl103549t.

Sources

- Mark Fox, Optical properties of solid,Oxford, New York, 2001.

- Hartmut Haug, Quantum Theory of the Optical and Electronic Properties of Semiconductors, World Scientific, 2004.

- http://www.rle.mit.edu/sclaser/6.973%20lecture%20notes/Lecture%2013c.pdf