Qaqortoq

| Qaqortoq Julianehåb | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| ||

Qaqortoq | ||

| Coordinates: 60°43′20″N 46°02′25″W / 60.72222°N 46.04028°WCoordinates: 60°43′20″N 46°02′25″W / 60.72222°N 46.04028°W | ||

| State |

| |

| Constituent country |

| |

| Municipality |

| |

| Founded | 1774 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Simon Simonsen | |

| Population (2013) | ||

| • Total | 3,229[1] | |

| Time zone | UTC-03 | |

| Postal code | 3920 | |

| Website | qaqortoq.gl | |

Qaqortoq,[2] formerly Julianehåb,[3] is a town in the Kujalleq municipality in southern Greenland. With a population of 3,229 in 2013,[1] it is the most populous town in southern Greenland and the fourth-largest town on the island.

History

The area around Qaqortoq has been inhabited since prehistoric times. Beginning with the Saqqaq culture roughly 4,300 years ago, the area has had a continuous human presence.

Saqqaq culture

The earliest signs of population presence are from roughly 4,300 years ago. While Saqqaq-era sites are generally the most numerous of all the prehistoric sites in Greenland, around Qaqortoq the Saqqaq presence is less prominent,[4] with only sporadic sites and items such as chipped stone drills[5] and carving knives.

Dorset culture

The Dorset people arrived in the Qaqortoq area around 2,800 years ago.[6] Several rectangular peat dwelling structures, characteristic of the early Dorset culture, can be found around the wider Qaqortoq area.

Norse culture

South Greenland history begins with the arrival of the Norse in the late 10th century. The ruins of Hvalsey – the most prominent Norse ruins in Greenland – are located 19 kilometers (12 mi) northeast of Qaqortoq. General or even limited trade between the Norse and the Thule people was scarce. Except a few novel and exotic items found at Thule sites in the area, evidence suggests cultural exchange was initially sporadic. Later, the south Greenland Norse adopted trade with the southern Inuit and were for a time the major supplier of ivory to northern Europe.[citation needed] The Norse era lasted for almost five hundred years, ending in the mid-15th century. The last written record of the Norse presence is of a wedding in the Hvalseyjarfjord church in 1408.[7]

Thule people

The Thule culture Inuit arrived in southern Greenland and the Qaqortoq area around the 12th century and were contemporaneous with the Norse. However, there exists little evidence of early contact. The Thule culture was characterized by a subsistence existence and there are few, if any, dwellings of considerable structure to be found from the era. Items, however, are relatively numerous.

Colonial era until present

The present-day town was founded in 1774 by the Dano-Norwegian trader Anders Olsen, on behalf of the General Trading Company.[8] The town was christened Julianehaab after the Danish queen Juliane Marie, although it sometimes mistakenly appears as "Julianshaab".[9] The name was also sometimes anglicized as Juliana's Hope.[10] The town became a major center for the saddle-back seal trade[11] and today remains the home of the Great Greenland sealskin tannery.

Until December 31, 2008, the town was the administrative center of Qaqortoq municipality. On January 1, 2009, Qaqortoq became the biggest town and the administrative center of Kujalleq municipality, when the municipalities of Qaqortoq, Narsaq, and Nanortalik ceased to exist as administrative entities.

Landmarks

Historical buildings

The building that now houses the Qaqortoq museum was originally the town's blacksmith's shop. The house was built in yellow stone and dates back to 1804.

The oldest standing building at the historical colonial harbor – and thus of all of Qaqortoq – is a black-tarred log building from 1797.[12] The building was designed by royal Danish architect Kirkerup, pre-assembled in Denmark, shipped in pieces to Qaqortoq, and then reassembled.

Stone & Man

From 1993 to 1994 Qaqortoq artist Aka Hoegh presided over the Stone & Man project, designed to transform the town into an open air art gallery. Eighteen artists from Finland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Greenland and Aland carved 24 sculptures into the rock faces and boulders in the town. Today there are over 40 sculptures in the town, all part of the Stone & Man exhibit.

The Fountain

The town is home to the oldest fountain in Greenland, Mindebrønden, built in 1927.[13] It was the only fountain in the country prior to another in Sisimiut. A tourist attraction, the fountain depicts whales spouting water out of their blowholes.[14]

Transport

Air

Qaqortoq Heliport operates year-round, linking Qaqortoq with Narsarsuaq Airport and, indirectly, with the rest of Greenland and Europe. Feasibility assessments are underway regarding building a landing strip for fixed-wing aircraft. The issue was previously debated in 2007, when the Democrats opposed a Siumut landing strip proposal,[15] citing ecological and environmental concerns. In contrast to the previous debates, presently the Democrats are lobbying for a 1,799-meter (5,902 ft) runway, making passenger flights to continental Europe possible. A shorter, 1,199-meter (3,934 ft) runway, supported by Siumut and Air Greenland,[16] would enable flights to Iceland and eastern Canada.[17] The cost of moving the airport from Narsarsuaq is estimated at DKK900 million (€120.7m, US$177m).[18] Presently Narsarsuaq airport directly and indirectly employs 140 people, and thus the regional council opposes the plans, citing employment concerns if the airport is closed.[19]

Presently five locations for a possible airport are being assessed. Four of these – at Prinsessen, Nunarsuatsiaap Kujalequtaa, Munkebugten, and halfway towards Narsaq – are for a 1,199-meter (3,934 ft) domestic runway. Only one location, northwest of the town between Nuupiluk and Matup Tunua, would be suitable for a runway up to 2,100 meters (6,900 ft), in order to accommodate intercontinental flights.

Land

As is true of all populated places in Greenland, Qaqortoq is not connected to any other place via roads. Fairly well trodden hiking trails lead north and west from the town, but for any motorized transportation terrain vehicles are needed. During winter, snowmobiles become the transport of choice.

Sea

Qaqortoq is a port of call for the Arctic Umiaq ferry.[20] The port authority for Qaqortoq is Royal Arctic Line, located in Nuuk. With a channel depth of 50 feet (15 m), the port can accommodate vessels up to 500 feet (150 m) in length.[21] The port offers pilotage upon request, but no tugging.

Economy and infrastructure

Qaqortoq is a seaport and trading station. Fish and shrimp processing, tanning, fur production, and ship maintenance and repair are important activities, but the economy is based primarily on educational and administrative services. The primary industries in the town are fishing, service, and administration.[22]

The native subsistence economy was long preserved by the former monopoly Royal Greenland Trading Department, which used the town as a source of saddle-back seal skins.[11] Today, the Great Greenland Furhouse remains one of the major employers in the town and is the primary sealskin purchaser on the island. Like the rest of Greenland, Qaqortoq is critically dependent upon investment from Denmark and relies heavily on Danish block funding. Of all exports produced in Qaqortoq, 70.1% are headed for the Danish market.[23]

Employment

As with the rest of Greenland, unemployment in south Greenland – and thereby Qaqortoq – remains high. In 2010, the unemployment was at 10.4%,[24] an increase of over 1.2% since 2009. For workers born outside Greenland unemployment was at 0.1% of the total eligible workforce during the same period.

Energy

All of Qaqortoq's electricity is supplied by the government-owned company Nukissiorfiit. Since 2007, Qaqortoq gets its electric power mainly from Qorlortorsuaq Dam by way of a 70-kilometer (43 mi) 70 kV powerline. Previously the town's electricity was supplied by means of so-called "bunker fuel generators",[25] three diesel ship engines converted to energy production.[26]

Education

Qaqortoq is the main center for education in South Greenland and has a primary school, middle school, and high school, a folk high school which started as a workers' college (Sulisartut Højskoliat) in 1977, a school of commerce, and a basic vocational school.[27]

Healthcare

Qaqortoq is served by Napparsimavik Hospital, officially Napparsimavik Qaqortoq Sygehus. The hospital is also the main hospital in southern Greenland. With a staff of 59 people, presently the hospital has 18 beds.[28] The three villages in Qaqortoq municipality – Eqalugaarsuit, Saarloq, and Qassimiut – also belong to the healthcare district of Napparsimavik Hospital. The villages are visited via sea and with a medical helicopter in case of emergencies. During the summer of 2010, the hospital used Greenland-grown vegetables exclusively.[29]

Tourism

Tourism is a significant contributor to the economy of the town. The Qaqortoq Tourist Service – Greenland Sagalands – is the tourist office. Roughly two-thirds of all tourists (65.5%) are from Denmark.[23] There are several facilities offering accommodations, including the Qaqortoq Hostel. The Qaqortoq Museum offers services in English, Danish, and Kalaallisut. The Great Greenland Furhouse is also a popular tourist attraction. Tourists are offered year-round activities such as kayaking, guided hiking, whale-watching, cross-country skiing, and boating. In recent years, Qaqortoq has experienced a decline in tourist revenue, with an average of 1,700 tourists annually staying in the town overnight.[30]

Demographics

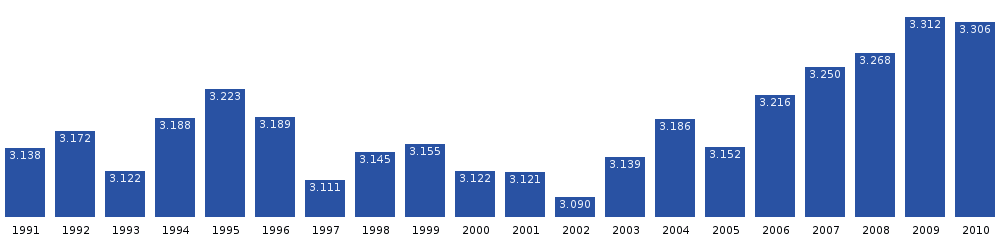

With 3,229 inhabitants as of 2013, Qaqortoq is the largest town in the Kujalleq municipality.[1] The population is nearly unchanged from its 1995 levels.

There exists no gender imbalance among native Greenlanders in Qaqortoq, the only gender inequity is amongst inhabitants born outside Greenland, with 3 out of 5 being male. As of 2011 10% of the town's inhabitants were born outside Greenland, a decline from 20% in 1991, but an increase from a 9% low in 2001.[31]

Geography

Qaqortoq is located at approximately 60°43′20″N 46°02′25″W / 60.72222°N 46.04028°W in the Qaqortoq Fjord, beside the Labrador Sea.

Climate

Qaqortoq has a maritime-influenced polar climate with cold, snowy winters and cool summers. The southern tip of Greenland does not experience permafrost.[32]

| Climate data for Qaqortoq, Greenland (1961-1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | −2.2 (28) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

2.8 (37) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.1 (52) |

11.0 (51.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

3.9 (39) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

3.95 (39.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −9.2 (15.4) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

3.3 (37.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−5.0 (23) |

−7.8 (18) |

−2.96 (26.68) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 57 (2.24) |

51 (2.01) |

57 (2.24) |

56 (2.2) |

56 (2.2) |

75 (2.95) |

97 (3.82) |

93 (3.66) |

92 (3.62) |

72 (2.83) |

78 (3.07) |

73 (2.87) |

857 (33.71) |

| Source: Danish Meteorological Institute[33] | |||||||||||||

Twin towns

Qaqortoq is twinned with:

-

Aarhus, Denmark

Aarhus, Denmark

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qaqortoq. |

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Greenland in Figures 2013. Statistics Greenland. ISBN 978-87-986787-7-9. ISSN 1602-5709. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ↑ The name is the Kalaallisut for "White". The pre-1973 spelling was Kakortok. The pronunciation of both sounds like

this (help·info).

this (help·info). - ↑ The pre-1948 spelling was Julianehaab.

- ↑ Bjarne Grønnow. "Saqqaq culture chronology". National Museum of Denmark. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Bifacial tool/projectile point". National Museum of the American Indian. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Early Dorset / Greenlandic Dorset". National Museum of Denmark. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ↑ Kenn Harper (2 August 2012). "Taissumani: Sept. 16, 1408 – Wedding at Hvalsey Church". Nunatsiaq Online.

- ↑ Marquardt, Ole. "Change and Continuity in Denmark's Greenland Policy" in The Oldenburg Monarchy: An Underestimated Empire?. Verlag Ludwig (Kiel), 2006.

- ↑ Colton, G.W. "Northern America. British, Russian & Danish Possessions In North America." J.H. Colton & Co. (New York), 1855.

- ↑ Lieber, Francis & al. Encyclopædia Americana: A Popular Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature, History, Politics and Biography. "Greenland". B.B. Mussey & Co., 1854.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kane, Elisha Kent. Arctic Explorations: The Second Grinnell Expedition. 1856.

- ↑ Lynn Kauer. "Qaqortoq". Retrieved April 6, 2011.(English)

- ↑ Greenland.com "The Official Tourism and Business Site of Greenland". Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ↑ O'Carroll, Etain (2005). Greenland and the Arctic. Lonely Planet. p. 115. ISBN 1-74059-095-3.

- ↑ "Ufred hos Demokraterne" (in Danish). Greenlandic Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- ↑ "Air Greenland støtter forslag om Qaqortoq lufthavn" (in Danish). Greenlandic Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Lufthavn i Qaqortoq. Ja, tak" (in Danish). Kamikposten. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Turismeerhvervet i Sydgrønland frygter nye lufthavnsplaner" (in Danish). Greenlandic Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Rungende nej til flytning af lufthavn" (in Danish). Greenlandic Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ↑ "AUL, Timetable 2009" (PDF). Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Port Qaqortoq, Greenland". SeaRates - Sea Freight Exchange. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Information about the town Qaqortoq". Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Greenland in figures 2009" (PDF).

- ↑ "Unemployment first 6 months 2010" (PDF) (in Danish). Statistics Greenland.

- ↑ "Arctic Sunrise, Greenpeace USA". Greenpeace USA. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- ↑ "QORLORTORSUAQ – Hydroelectric Project". Verkis. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- ↑ "Blue Ice Explorer". Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Napparsimavik Qaqortoq Sygehus" (in Danish).

- ↑ "Yum yum". Sikunews. October 14, 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Tourisme - Qaqortoq Kommunia 2004-2014" (PDF) (in Danish). Kujalleq Municipality. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ↑ "Statistics Greenland". Statistics Greenland. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ↑ Nyegaard, Georg (2009). Journal of the North Atlantic - Restoration of the Hvalsey Fjord Church. Eagle Hill Foundation. p. 192.

- ↑ Danish Meteorological Institute |language=Danish

| |||||||||||