Pythagorean field

In algebra, a Pythagorean field is a field in which every sum of two squares is a square: equivalently it has Pythagoras number equal to 1. A Pythagorean extension of a field F is an extension obtained by adjoining an element √1 + λ2 for some λ in F. So a Pythagorean field is one closed under taking Pythagorean extensions. For any field F there is a minimal Pythagorean field Fpy containing it, unique up to isomorphism, called its Pythagorean closure.[1] The Hilbert field is the minimal ordered Pythagorean field.[2]

Properties

Every Euclidean field (an ordered field in which all positive elements are squares) is an ordered Pythagorean field, but the converse does not hold.[3] A quadratically closed field is Pythagorean field but not conversely (R is Pythagorean); however, a non formally real Pythagorean field is quadratically closed.[4]

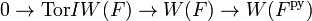

The Witt ring of a Pythagorean field is of order 2 if the field is not formally real, and torsion-free otherwise.[1] For a field F there is an exact sequence involving the Witt rings

where I W(F) is the fundamental ideal of the Witt ring of F[5] and Tor I W(F) denotes its torsion subgroup (which is just the nilradical of W(F).[6]

Equivalent conditions

The following conditions on a field F are equivalent to F being Pythagorean:

- The general u-invariant u(F) is 0 or 1.[7]

- If ab is not a square in F then there is an order on F for which a, b have different signs.[8]

- F is the intersection of its Euclidean closures.[9]

Models of geometry

Pythagorean fields can be used to construct models for some of Hilbert's axioms for geometry (Ito 1980, 163 C). The coordinate geometry given by Fn for F a Pythagorean field satisfies many of Hilbert's axioms, such as the incidence axioms, the congruence axioms and the axioms of parallels. However, in general this geometry need not satisfy all Hilbert's axioms unless the field F has extra properties: for example, if the field is also ordered then the geometry will satisfy Hilbert's ordering axioms, and if the field is also complete the geometry will satisfy Hilbert's completeness axiom.

The Pythagorean closure of a non-archimedean ordered field, such as the Pythagorean closure of the field of rational functions Q(t) in one variable over the rational numbers Q, can be used to construct non-archimedean geometries that satisfy many of Hilbert's axioms but not his axiom of completeness.[10] Dehn used such a field to construct two Dehn planes, examples of non-Legendrian geometry and semi-Euclidean geometry respectively, in which there are many lines though a point not intersecting a given line but where the sum of the angles of a triangle is at least π.[11]

Diller–Dress theorem

This theorem states that if E/F is a finite field extension, and E is Pythagorean, then so is F.[12] As a consequence, no algebraic number field is Pythagorean, since all such fields are finite over Q, which is not Pythagorean.[13]

Superpythagorean fields

A superpythagorean field F is a formally real field with the property that if S is a subgroup of index 2 in F∗ and does not contain −1, then S defines a ordering on F. An equivalent definition is that F is a formally real field in which the set of squares forms a fan. A superpythagorean field is necessarily Pythagorean.[12]

The analogue of the Diller–Dress theorem holds: if E/F is a finite extension and E is superpythagorean then so is F.[14] In the opposite direction, if F is superpythagorean and E is a formally real field containing F and contained in the quadratic closure of F then E is superpythagorean.[15]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Milnor & Husemoller (1973) p. 71

- ↑ Greenberg (2010)

- ↑ Martin (1998) p. 89

- ↑ Rajwade (1993) p.230

- ↑ Milnor & Husemoller (1973) p. 66

- ↑ Milnor & Husemoller (1973) p. 72

- ↑ Lam (2005) p.410

- ↑ Lam (2005) p.293

- ↑ Efrat (2005) p.178

- ↑ (Ito 1980, 163 D)

- ↑ Dehn (1900)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lam (1983) p.45

- ↑ Lam (2005) p.269

- ↑ Lam (1983) p.47

- ↑ Lam (1983) p.48

References

- Dehn, Max (1900), "Die Legendre'schen Sätze über die Winkelsumme im Dreieck", Mathematische Annalen 53 (3): 404–439, doi:10.1007/BF01448980, ISSN 0025-5831, JFM 31.0471.01

- Efrat, Ido (2006), Valuations, orderings, and Milnor K-theory, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs 124, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-4041-X, Zbl 1103.12002

- Elman, Richard; Lam, T. Y. (1972), "Quadratic forms over formally real fields and pythagorean fields", American Journal of Mathematics 94: 1155–1194, ISSN 0002-9327, JSTOR 2373568, MR 0314878

- Greenberg, Marvin J. (2010), "Old and new results in the foundations of elementary plane Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries", Am. Math. Mon. 117 (3): 117–219, ISSN 0002-9890, Zbl 1206.51015

- Iyanaga, Shôkichi; Kawada, Yukiyosi, eds. (1980) [1977], Encyclopedic dictionary of mathematics, Volumes I, II, Translated from the 2nd Japanese edition, paperback version of the 1977 edition (1st ed.), MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-59010-5, MR 591028

- Lam, T. Y. (1983), Orderings, valuations and quadratic forms, CBMS Regional Conference Series in Mathematics 52, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-0702-1, Zbl 0516.12001

- Lam, T. Y. (2005), "Chapter VIII section 4: Pythagorean fields", Introduction to quadratic forms over fields, Graduate Studies in Mathematics 67, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, pp. 255–264, ISBN 978-0-8218-1095-8, MR 2104929

- Martin, George E. (1998), Geometric Constructions, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-98276-0

- Milnor, J.; Husemoller, D. (1973), Symmetric Bilinear Forms, Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete 73, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-06009-X, Zbl 0292.10016

- Rajwade, A. R. (1993), Squares, London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series 171, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-42668-5, Zbl 0785.11022