Pyramid Building Society

The Pyramid Building Society, the Geelong Building Society and the Countrywide Building Society together made up the Farrow Group of building societies, based in Geelong, Australia. They collapsed in 1990 with debts in excess of $2 billion. The cost of the collapse to the Victoria taxpayers was estimated at over $900 million, causing a fuel levy of 3c-per-litre to be introduced by the Victorian Government to recover funds. The levy remained in force for five years.

Origins

Pyramid was established in 1959 by Vautin Andrews and Bob Farrow, with a view to helping the city grow. Andrews was later mayor of Geelong and Farrow was an accountant and his firm managed the society. When legislation changed in the mid 1960s to allow building societies to take deposits from the public Pyramid grew rapidly. When Bob Farrow's health suffered in the late 1970s his son Bill Farrow took over much of the operation, and Andrews' son Bruce Andrews also worked for the society. Pyramid took over control of its competitor the Geelong Building Society in 1971. That society had origins going back to 1867 and had been operated very conservatively.

In 1983 the rules for Pyramid and Geelong were changed to allow shares representing ownership of the societies to be issued, and the Farrow Group controlled by the Farrow family asserted that they as managers should get most of them. After the collapse the basis for this assertion was disputed, but Farrow ended up as owner of a substantial business for a very modest outlay of money. In 1984 the Farrow Group also took over the small Third Extended Starr-Bowkett Building Society and renamed it the Countrywide Building Society. At the time of the collapse the group was headed by Bill Farrow and former Geelong Football Club player David E. Clarke.

Collapse

In early 1990 there was a sudden run on Pyramid as depositors rushed to withdraw their money. The reasons behind this were never established, though it was suspected some rumours might have been started by rival institutions. On 13 February 1990 the state treasurer Rob Jolly and attorney general Andrew McCutcheon held a press conference and assured the public that Pyramid was sound, all but telling them to stay in. In fact Pyramid wasn't sound, but the office of the Registrar of Building Societies hadn't been particularly assiduous and so didn't know that.

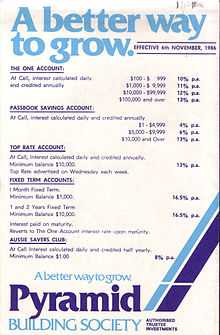

After the run Pyramid mounted an advertising campaign to attract more deposits, offering markedly higher interest rates than competitors. Behind the scenes it was borrowing money, selling assets, and trying to find a merger partner. The ANZ Bank was about the only major potential partner. The group's value was in the branch network and strong customer loyalty, but the question was how many bad loans it was carrying.

A second run of withdrawals began in May 1990 and at that time premier John Cain apparently tried to get a deal up with the ANZ by offering a $90m government guarantee, but the ANZ had lost interest. In June the government suspended withdrawals for a week and appointed an administrator. Cain announced there was no government guarantee of deposits, unleashing a storm of outrage at the contrast with the government's initial advice.

The administrator's report on 1 July 1990 was that the societies had to be wound up. On the morning of 3 July the premier was still saying there was no government guarantee, but by the afternoon he'd been rolled by his own caucus and had to announce that there would in the end be a guarantee.

Regulation

Building societies in Victoria came under the Registrar of Building Societies, a position held by David LaFranchi at that time. LaFranchi had formerly headed the Cooperatives and Societies Division in the corporate affairs department, but his office lacked both legislative powers (in the Building Societies Act of 1986) and enough staff to supervise 250 deposit-taking institutions.

If the registrar discovered a society in difficulty the only real power available was to order a merger with another society. Yet by the time Pyramid was in trouble, the conversion of the RESI Statewide Building Society to become a bank (the Bank of Melbourne) had left the Farrow Group with some 55% of the Victorian market, meaning there was no other society big enough to make a merger useful.

This situation in Victoria was a little unusual. When runs of withdrawals had threatened building societies in the 1970s they got together to form an Australia-wide National Deposit Insurance Corporation to protect depositors, with standby credit and minimum prudential ratios for member societies to observe. The Victorian government of the time had chosen not to participate in that scheme, believing the government could regulate and supervise societies.

Bad loans

The vast majority of the losses suffered by Pyramid and the whole Farrow Group had been from ventures into commercial property, frequently lending aggressively to speculative projects. Doubtful loans were hidden in the books by various techniques, such as capitalizing fees and interest into the loan balance, changing the loan conditions, or even selling the property into a subsidiary company for a price that covered the debt. Staff were paid a commission on new lending business, which is proper enough, but also for improving bad loans, which gave them an incentive to rearrange the affairs of borrowers who were in default.

The Farrow Group also operated on much smaller interest rate margins (between rates received from borrowers and paid to depositors or wholesale lenders) than other finance groups. This was a deliberate strategy, set out by Bill Farrow in the group's 1986 annual report. He expected deregulation to force down what had traditionally been quite wide margins, to be replaced by an emphasis on fees for services. He was correct in that analysis, but in accepting small spreads the group was particularly vulnerable if bad loans reduced their effective interest income.

Non-withdrawable shareholders

Pyramid had offered to customers a class of "non-withdrawable investing shares" which paid interest like a time deposit, but at a higher interest rate. Many customers who took them up were apparently unaware of the distinction between shares and deposits, and staff were paid commissions for selling the shares so were presumably not particularly motivated to make the difference clear.

Those shares ranked behind depositors in a wind-up, so after the collapse those shareholders stood to receive nothing at all. Their plight dragged on for a very long time. In 1992 they had a setback when the Victorian Supreme Court confirmed that they ranked behind depositors. One of the holders, Phillip Lauren, then sued the government and ministers on the basis he had been misled by their advice to keep his money in, and a group of the shareholders marched on state parliament in September 1992.

When the government changed the new treasurer Alan Stockdale was also not inclined to rank the non-withdrawable shareholders with depositors. In fact he was even less sympathetic than Cain's government had been, believing Cain shouldn't even have guaranteed the ordinary deposits.

Subsequently

In 2003, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade awarded a grant of A$90,000 to Geelong based company, World Wide Entertainment, headed by Farrow Group head, Bill Farrow.[1] On 23 March 2008 Warren Meyer, a former bankrupt who owed $2.3M to the Pyramid Building Society, went missing on a bushwalk.[2]

References

- Trevor Sykes, The Bold Riders, second edition, 1996, ISBN 1-86448-184-6.

- ↑ Outrage over grant to former head of Pyramid, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2 December 2003

- ↑ Missing Hiker, The Age, 19 April 2008

External links

- Australian Government Treasury, Financial institution failures in Australia - Case Study (PDF file)

- Jambrecina v Pyramid Building Society Ltd (In Liq) & Anor (2004), High Court of Australia, Application for special leave to appeal

- Pyramid chief gets $90,000 trade grant, The Age, 2 December 2003

- Rubbery Figures Cartoon