Purple Line (Maryland)

| Purple Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Light rail transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | Maryland Transit Administration | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale |

Montgomery County, MD and Prince George's County, MD | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini |

Bethesda (west) New Carrollton (east) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 21 (planned)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily ridership | 64,800 daily by 2030[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opening | 2020 (planned)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | TBD | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | TBA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track length | 16.3 miles[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | TBA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

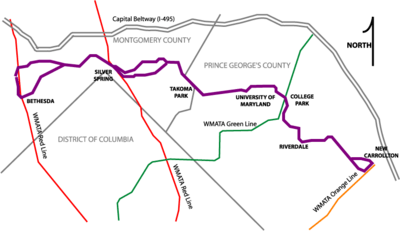

The Purple Line, previously designated as the Bi-County Transitway, is a proposed 16-mile (25 km) transit line to link the Red, Green, and Orange lines of the Washington Metro transportation system in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C.[3] The project is currently being administered by the Maryland Transit Administration (MTA). On October 7, 2011 the proposed light rail line received Federal Transit Administration approval to enter the detailed engineering phase which, according to the Washington Post, is "a significant step forward in its decades-long trek toward construction."[4]

History

The Purple Line was conceived as a rail line from New Carrollton to Silver Spring. Maryland's Glendening administration (which included John Porcari as Secretary of Transportation) removed the heavy rail option from planning discussion because it was felt that the cost was greater than the need.

Robert Flanagan, the Maryland State Secretary of Transportation under Governor Robert Ehrlich, merged the Purple Line with another transportation project, Georgetown Branch Light Rail Transit (GBLRT). The GBLRT was proposed as a light rail transit line from Silver Spring westward, following the former Georgetown Branch of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (now a short CSX siding and the Capital Crescent Trail) to Bethesda.[3]

Both Governor Ehrlich and Secretary Flanagan introduced an alternative mode – bus rapid transit — that might have been utilized in lieu of light rail transit. To reflect this possibility, the administration changed the name of the project to the "Bi-County Transitway" in March 2003. Another reason that "the Purple Line" was discouraged by the Ehrlich administration was that its associations with the other color-oriented names of the Washington Metro system (which consists of heavy rail) might lead the public to expect a heavy rail option. The new name did not catch on, however, as several media outlets and most citizens continued to refer to the project as the Purple Line. As a result, Governor Martin O'Malley and Secretary of Transportation John Porcari opted to revert to "Purple Line" in 2007.[3]

In January 2008, the O'Malley administration allocated $100 million within a six-year capital budget to complete design documents for state approval and funding of the Purple Line.[5] In May 2008, it was reported that the Purple Line could carry about 68,000 daily trips.[6]

A draft environmental impact study was issued on October 20, 2008.[7] On December 22, 2008, Montgomery County planners endorsed building a light rail line rather than a bus line. On January 15, 2009, the county planning board also endorsed the light rail option,[8] and County Executive Isiah Leggett has also expressed support.[9] On October 21, 2009, members of the National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board voted unanimously to approve the Purple Line light rail project for inclusion into the region’s Constrained Long-Range Transportation Plan.[10]

Even though the project is currently overseen by the Maryland Transit Administration (MTA), it is not yet clear who would operate the Purple Line if it were constructed. MTA representative Michael Madden said that the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) has been working with the MTA to develop the Purple Line. The future transit system could be operated by the state of Maryland, by WMATA, or by Montgomery and Prince George's counties. Regardless, planners intend to utilize current Metrorail stations and for the Purple Line to accept WMATA's SmarTrip farecard.[11] Metro's 2008 annual report asks readers to imagine that in 2030 the Purple Line will be integrated with WMATA's existing transit system.[12][13]

Route and station locations

The planned rail or rapid bus line will connect the existing Metro, MARC commuter rail, and Amtrak stations at:[14]

- Bethesda (Metro Red Line)

- Silver Spring (Metro Red Line), MARC Brunswick Line

- College Park (Metro Green Line), MARC Camden Line

- New Carrollton (Metro Orange Line), MARC Penn Line, Amtrak Northeast Corridor (Northeast Regional, Vermonter)

The following stations are part of the "Locally Preferred Alternative" route approved by Governor Martin O'Malley on August 9, 2009:[15]

- Bethesda

- Connecticut Avenue in Chevy Chase

- Lyttonsville Road in Silver Spring

- 16th Street in Silver Spring

- Silver Spring Metro Center

- Silver Spring Library, Fenton Street

- Dale Drive in Silver Spring (proposed to be built after initial construction)

- Manchester Road in Silver Spring

- Arliss Street in Silver Spring

- Gilbert Street in Takoma Park

- Takoma Park-Langley Park Transit Center

- Riggs Road

- Adelphi Road in Hyattsville

- University of Maryland, campus center

- University of Maryland, east campus

- U.S. Route 1 in College Park

- River Road in Riverdale Park

- Kenilworth Avenue in Riverdale Park

- Riverdale Road in Riverdale

- Annapolis Road near Landover Hills

- New Carrollton Metro Center

Potential further expansion

Although the majority of discussions about the Purple Line describe the project as a 16-mile east-west line between Bethesda and New Carrollton,[14] there have been several proposals to expand the line further into Maryland or to mirror the Capital Beltway as a loop around the entire Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. The Sierra Club has argued for a Purple Line which would "encircle Washington, D.C." and "connect existing suburban metro lines."[16] Maryland Lieutenant Governor Anthony G. Brown, while campaigning in 2006, similarly stated that he'd "like to see the Purple Line go from Bethesda to across the Woodrow Wilson Bridge," adding, "Let’s swing that boy all the way around" (a reference to having the Purple Line circle through Virginia and back to the line's point of origin in Bethesda).[17]

An advocacy group known as "The Inner Purple Line Campaign" has stated that the Purple Line could be extended westward to Tysons Corner and eastward to Largo, and that it could eventually cross the new Wilson Bridge from Suitland through Oxon Hill to Alexandria, eventually forming a rail line that encircles the city.[18] The reconstruction of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge (I-495's southern crossing over the Potomac River) provides capacity for the bridge to carry a heavy or light rail line.[19] Suggested stops along this proposed Purple Line expansion include:[20]

- Largo Town Center

- Branch Avenue

- Oxon Hill (potentially near Rosecroft Raceway, at which Metro has at times had plans to build a stop since 1980[21])

- National Harbor

- Alexandria, potentially the King Street – Old Town Metro station

- Springfield

- Annandale

- Dunn Loring

- Tysons Corner

Community support and opposition

Support for rail

- Purple Line Now is an non-profit specifically dedicated to advocating for the inside the beltway light rail Purple Line from Bethesda to New Carrollton integrated with a hiker/biker trail from Bethesda to Silver Spring.[22]

- The Action Committee for Transit is a community group that supports the Purple Line.[18]

- The Washington Post advocates construction of the Purple Line light rail option.[23]

- The Montgomery County Council and Prince George's County Council voted unanimously in favor of the light rail option for the Purple Line in January 2009.[24][25]

- State officials (including Governor O'Malley, Dem.) are also strong Purple Line advocates. State officials say that a Purple Line, which would run primarily above ground, "would provide better east-west transit service, particularly for lower-income workers who can't afford cars."[26]

- The development firm Chevy Chase Land Co. is a strong proponent of the construction of the Purple Line. The website for the pro-Purple umbrella group Purple Line NOW! lists Edward Asher as a member of its board of directors. The Washington Post indicates that the development firm would "no doubt profit from property it owns near at least one of the proposed stations."[26]

- The Sierra Club advocates a larger-scale rail system to parallel the Capital Beltway and link all existing Metro lines at their peripheries. This environmental group advocates rail transit over car use because carbon emissions are a major risk factor for global warming.[27]

- Some student leaders (the Student Government Association and Graduate Student Government) at the University of Maryland support transit alternatives to campus.[28][29]

- On January 27, 2009, the Montgomery County Council voted to support the light rail option.[30] Governor O'Malley announced his own approval on August 4, 2009.[1]

- The vice president of trail development for the Rails to Trails conservancy has gone on record citing rail-trail combinations around the country and arguing that with proper design, the trail-purple-line combination can be "among the best in the nation." [31]

Support for bus

- A 2008 study by Sam Schwartz Engineering for the Town of Chevy Chase supported bus rapid transit using an alternate Jones Bridge Road alignment. The Chevy Chase study expressed concerns about the expected ridership numbers, carbon footprint, interruptions in recreation pathways, and the cost of bus and light rail proposals by the MTA involving a Capital Crescent Trail alignment. Although a Jones Bridge Road alignment was also proposed by the MTA, the study noted that features typical of bus rapid transit that were missing from the MTA proposal.[32]

Opposition to rail

- An unincorporated local organization, Save the Trail Petition, has been collecting signatures on a petition opposing the MTA's Purple Line proposals since 2003. The organization's website explains that the MTA's light rail and bus rapid transit proposals will have significant environmental and safety impacts on the Capital Crescent Trail.[33] Alternatives suggested by the organization's website included the Jones Bridge Road alignment for bus rapid transit recommended by the Chevy Chase study.[32] Save the Trail Petition prefers alternatives, however, noting that a Jones Bridge Road alignment would also have some impact on the trail.[34]

- A leading opponent of the Purple Line is the Columbia Country Club, a golf course with land that occupies both sides of the planned route between Bethesda and Silver Spring.[35]

- Opponents in the Town of Chevy Chase cited the town's study of bus rapid transit alternatives. The study estimated a cost of less than $1 billion for a bus rapid transit system, compared with an estimated cost of $1.8 billion for light rail.[36] A 2011 news report placed the cost of the rail line at US$1.93 billion.[37]

- Some Silver Spring residents are concerned that one of the proposed routes will take houses along Thayer Avenue, cross behind East Silver Spring Elementary School, take over an acre of Sligo Creek Park, and bring noise to a residential neighborhood.[citation needed]

- Residents around the Dale Wayne stop are concerned that doubling the size of the road, along with the county's "smart growth" policy around transit stops, will encourage commercial development in a residential neighborhood. Their concerns have also questioned whether the 1,427 daily boardings anticipated by the MTA by 2030 is a realistic figure for the Dale station.[38][39]

Responses for and against light rail

Common responses to opposition points, and responses in turn to them, include the following:

Pro-rail:

- The Purple Line will not destroy the Capital Crescent Trail, but will exist adjacent to it.[40]

- From an environmental perspective, the environmental benefits of increased transit use, such as lower vehicle emissions, more than offset the removal of trees along the route.[41]

- The Purple Line will allow the final 1.5-mile section of the Capital Crescent Trail to be completed into Silver Spring as an off-road trail and will reduce the number of at-grade crossings.[42]

- The right-of-way for the Capital Crescent Trail was purchased by the state of Maryland specifically for a transit line, so the trail would not exist if not for the transit line.[43]

- Bus rapid transit is not as efficient (due to reduced speed and higher emissions) as light rail.[44]

- The suggested alternate route along Jones Bridge Road between Bethesda and Silver Spring is indirect and slower than the Capital Crescent route.[44]

Anti-rail:

- The proposed routing will clear-cut thousands of mature trees and replace a linear park with a paved sidewalk adjacent to a pair of high speed rail lines. (This assertion is highly suspect, given its uncited nature and the Rails-to-Trails endorsement.)

- To achieve lower carbon dioxide output when compared with cars, light rail transit vehicles may require a significantly greater number of passengers than buses. Size of vehicles, frequency of braking and acceleration, and traffic impact of rail and bus should be considered.[45]

- The Capital Crescent Trail extension into Silver Spring was part of all build alternatives in the AA/DEIS document prepared by MDOT. It was not limited to the light rail alternatives.[46]

- A right-of-way was purchased through the rails-to-trails program, and rail supporters are only proposing a small portion of the length for conversion back to rail. There is not an obligation from law or practice to regress a trail back to rail. (Again, somewhat strongly negated by the Rails to Trails endorsement cited above.)

- A rail system would make local traffic worse by reducing capacity of small suburban roads, adding more stops, and possibly car/rail collisions.

- A bus rapid transit system would cost 30 percent less to build, reduce overall travel time for most riders, and may also reduce overall air pollution (see pages 6–8 of the Chevy Chase Analysis of MTA Purple Line).[32]

- Use of buses would allow integration with the county or WMATA bus transit system, rather than operating as an isolated line.

- An alignment along Jones Bridge Road would serve more passengers than an alignment along the Capital Crescent Trail. Speed is a function of the number of at-grade crossings, not the type of vehicle.[34]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Governor O'Malley Announces Purple Line Locally Preferred Alternative MDOT press release 2009-8-4, retrieved 2009-12-3

- ↑ Project Schedule

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Purple Line Overview MTA Maryland website. Retrieved 2010-1-7

- ↑ Ovetta Wiggins (2011-10-07). "Plans for Purple Line move forward in Maryland". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2011-10-08.

- ↑ Davis, Janel (2008-01-18). "O’Malley allocates $100M for Purple Line planning". The Gazette (Maryland). Post-Newsweek Media. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ Katherine Shaver (2008-05-30). "Trips on Purple Line Rail Projected at 68,000 Daily". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- ↑ Maryland Transit Administration (2008-10-20). "Project Alternatives Analysis/Draft Environmental Impact Statement (AA/DEIS)". MTA (Maryland). MTA. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ Miranda S. Spivak (2009-01-16). "Montgomery Planners Back Rail". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ Katherine Shaver (2009-01-23). "Leggett Endorses Light-Rail Plan". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ TPB News Vol XVII Issue 4 p. 1 (November 2009). "TPB Gives Final Approval to Purple Line Project". Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ↑ "Public Meeting on the Purple Line". Town of Chevy Chase, Maryland. 2007-06-06. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ↑ "2008 Annual Report". Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ↑ "Metro preparing for more people to shift to transit if gasoline prices continue to skyrocket". WMATA. 2008-05-22. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Purple Line Facts".

- ↑ Purple Line Conceptual Plans: Project Area Map MTA Maryland

- ↑ "Purple Line". Sierra Club. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ Thomas Dennison and Douglas Tallman (2006-10-04). "Brown’s ‘lofty’ Purple Line plans draw fire from transportation officials". Gazette.Net. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 What is the Purple Line?, The Inner Purple Line Campaign, a project of the Action Committee for Transit (ACT), retrieved 2009-12-4

- ↑ Scott M. Kozel (2009-02-25). "Woodrow Wilson Bridge (I-495 and I-95)". Roads to the Future. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ↑ "Sierra Club Purple Line Map".

- ↑ Scott M. Kozel (2001-01-23). "Metrorail Branch Avenue Route Completion". Roads to the Future. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ↑ "Purple Line Now: Who We Are". Purple Line Now. Retrieved 2011-10-08.

- ↑ "Full Speed Ahead". The Washington Post. November 16, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ↑ Montgomery County Council votes 8-0 for medium light rail option (2009-1-27) Purple Line NOW! accessed 2010-1-6

- ↑ Prince George's County Council approves the new Transportation Master Plan (2009-1-17) Purple Line NOW! accessed 2010-1-6

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Katherine Shaver (2008-07-13). "Purple Line Foes Offer No Ideas, And No Names". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ "Purple Line". Sierra Club. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ↑ Katherine Shaver (May 13, 2007). "Students Urge Stronger Backing of Purple Line". The Washington Post. p. C04.

- ↑ "Letter from student leaders to UMD President" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ↑ Shaver, Katherine (2009-01-23). "Leggett Endorses Light-Rail Plan". The Washington Post. p. B03. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- ↑ Maynard, Patrick (2011-06-08). "Rails to Trails VP on Purple Line". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Analysis of MTA Purple Line Sam Schwartz Engineering, 2008-4-23, Study of BRT alternative for Town of Chevy Chase, retrieved 2009-12-1

- ↑ Save the Trail Petition

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Save the Trail Petition: Alternatives Studies of alternatives to a Capital Crescent Trail alignment, retrieved 2009-12-2

- ↑ Katherine Shaver (January 16, 2005). "Fortunes Shift for East-West Rail Plan". The Washington Post. p. C01.

- ↑ Katherine Shaver (July 7, 2008). "Chevy Chase Says Buses Beat Trains on Purple Line". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Luz Lazo (30 September 2011), "In Langley Park, Purple Line brings promise, and fears, of change", The Washington Post, retrieved 15 November 2011

- ↑ Jason Tomassini (May 12, 2010). "MTA pushing for additional Purple Line stop in Silver Spring". The Gazette.

- ↑ Purple Line study report (August 2009). "An evaluation of the merits of an LRT station at Dale Drive and Wayne Avenue". MTA Maryland. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ↑ The Purple Line and the Trail, The Inner Purple Line Campaign, a project of the Action Committee for Transit (ACT), retrieved 2009-12-4

- ↑ Better Transportation for Better Communities, The Inner Purple Line Campaign, a project of the Action Committee for Transit (ACT), retrieved 2009-12-4

- ↑ Silver Spring waits for the Capital Crescent Trail, Silver Spring Trails website, retrieved 2009-12-4

- ↑ Purple line haze: a history lesson Just Up the Pike blog (2007-8-16)

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Why We Support Rail for the Inner Purple Line The Inner Purple Line Campaign, a project of the Action Committee for Transit (ACT), retrieved 2009-12-4

- ↑ Purple Line Alternatives and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Maryland Politics Watch blog, 2008-12-22, retrieved 2009-12-4

- ↑ Environmental Resources, Inpacts, and Mitigation MDOT AA/DEIS document, Chapter 4 p. 85, retrieved 2009-12-4

See also

- Silver Line (Washington Metro), projected to open in 2013 (Phase I) and 2016 (Phase II)

External links

- State government

- County government

- Maps

- Washington Post map – dated January 31, 2009, based on updated MTA proposed stations

- Sierra Club Proposed Route – full loop not actually being studied

- Advocates

- Opponents

| KML file (edit) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||