Purchasing power

Purchasing power (sometimes retroactively called adjusted for inflation) is the number of goods or services that can be purchased with a unit of currency. For example, if one had taken one unit of currency to a store in the 1950s, it is probable that it would have been possible to buy a greater number of items than would today, indicating that one would have had a greater purchasing power in the 1950s. Currency can be either a commodity money, like gold or silver, or fiat currency, or free-floating market-valued currency like US dollars. As Adam Smith noted, having money gives one the ability to "command" others' labor, so purchasing power to some extent is power over other people, to the extent that they are willing to trade their labor or goods for money or currency.

If one's monetary income stays the same, but the price level increases, the purchasing power of that income falls. Inflation does not always imply falling purchasing power of one's money income since it may rise faster than the price level. A higher real income means a higher purchasing power since real income refers to the income adjusted for inflation.

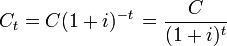

For a price index, its value in the base year is usually normalized to a value of 100. The purchasing power of a unit of currency, say a dollar, in a given year, expressed in dollars of the base year, is 100/P, where P is the price index in that year. So, by definition the purchasing power of a dollar decreases as the price level rises. The purchasing power in today's money of an amount C of money, t years into the future, can be computed with the formula for the present value:

where in this case i is an assumed future annual inflation rate.

See also

- Carrying capacity

- Collective buying power

- Constant Purchasing Power Accounting

- Consumer Price Index

- Consumerism

- Consumption (economics)

- Fair trade

- Free trade

- Group buy

- Group purchasing organization

- Inflation

- Measuring economic worth over time

- Oil burden

- Purchasing power parity

- Sustainability

References

External links

- MeasuringWorth.com has a calculator with different measures for bringing values in Pound sterling from 1264 to the present and in US Dollars from 1774 up to any year until the present. The Measures of Worth page discusses which would be the most appropriate for different things.

- Purchasing Power Calculator by Fiona Maclachlan, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.