Pueblo III Era

Archaic–Early Basketmaker Era

Archaic–Early Basketmaker Era7000 – 1500 BC Early Basketmaker II Era

1500 BC – AD 50 Late Basketmaker II Era

AD 50 – 500 Basketmaker III Era

AD 500 – 750 Pueblo I Era

AD 750 – 900 Pueblo II Era

AD 900 – 1150 Pueblo III Era

AD 1150 – 1350 Pueblo IV Era

AD 1350 – 1600 Pueblo V Era

AD 1600 – present

The Pueblo III Era, AD 1150 to 1350, was the third period, also called the "Great Pueblo period" when Ancient Pueblo People lived in large cliff-dwelling, multi-storied pueblo, or cliff-side talus house communities. By the end of the period the ancient people of the Four Corners region migrated south into larger, centralized pueblos in central and southern Arizona and New Mexico.

Pueblo III Era (Pecos Classification) is roughly the same as the "Great Pueblo Period" and "Classic Pueblo Period" (AD 1100 to 1300).

Architecture

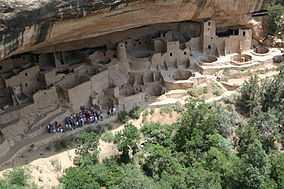

During the Pueblo III era most people lived in communities with large multi-storied dwellings. Some moved into community centers at pueblos canyon heads, such as Sand Canyon and Goodman Point pueblos in the Montezuma Valley; Others moved into cliff dwellings on canyon shelves such as Mesa Verde or Keet Seel in the Navajo National Monument. Typical villages had included kivas, towers, and dwellings made with triple coursed (three rows of stones) stone masonry walls.[1][2][3][4] T-shaped windows and doors emerged for both surface and cliff dwellings.[5]

- Cliff dwellings were built in shallow caves and under rock overhangs along canyon walls. In Mesa Verde, the structures within the alcoves were mostly made of sandstone blocks and adobe mortar. To build the dwellings, materials had to be brought to the alcove, such as fill dirt to level the cave floor, stones and mortar. Masonry craftsmanship became refined by this period. Stones were shaped and made smooth by pecking away at the surface, leaving a distinctive "dimpled" surface on the stone. The dwellings had sharp square corners. Walls were built to be thick enough to support multiple stories. Floors were made of wood, bark and mud. The most desired caves were those that faced south or southwest to reap the warmth of the winter sun. Doorways were small, covered with stone slabs for warmth. Exterior doorways were rarely built on the first floor. Ventilation holes in the ceilings held ladders for entry into the rooms. Plazas in front of the dwellings were used by women to grind corn, make baskets and clothing and prepare food. Men made their tools and children played there.[6]

- Surface masonry buildings. Not all of the people in the region lived in cliff dwellings; many colonized the canyon rims and slopes in multi-family structures that grew to unprecedented size as the population swelled.[3]

- Talus houses were built at the bottom of a cliff, often in front of "cavates" (cave rooms), and were about 5 feet, 8 inches high and 6 by 9 feet in surface area. The rooms were prepared by scooping soft tuff out of the cavity. Cavates is a term classified by archaeologist Edgar Lee Hewett.[7][8]

-

Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde National Park

-

Puerco Pueblo walls of up to 100-125 rooms at the Petrified Forest National Park[1]

-

Bandelier National Monument Talus House

-

Bandelier National Monument Cavates

Cite error: There are <ref> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist}} template (see the help page).

Communities

Three major regional centers with cliff dwellings and community centers were Chaco Canyon National Monument in New Mexico, Mesa Verde National Park in southwestern Colorado and Betatakin and Keet Seel area (Navajo National Monument) in Arizona[9]

- Bandelier cliff alcoves and caves contained soft volcanic tuff which was scooped out to enlarge the area for masonry dwellings. Logs of juniper and pinyon trees were used to create frames for willow sticks, grass, bark and earth for ceilings and upper floors.[10]

- Mesa Verde. Mug House, a typical cliff dwelling of the period, was home to around 100 people who shared 94 small rooms and eight kivas. Builders maximized space by abutting the pueblo rooms.[3][11] Population peaked about AD 1200 to 1250 to more than 20,000 in the Mesa Verde Region in Colorado.[1]

- Cowboy Wash, an archaeological site located on the southern slopes of Sleeping Ute Mountain, was inhabited during the Pueblo III period by people from the Chuska Mountains area of Arizona and New Mexico. They moved north and settled in the Montezuma Valley after the collapse of the Chaco culture,[12] which had suffered due to a great drought from AD 1130 - 1180.[13] From excavation of Cowboy Wash, four sites were found to be the scene of a violent attack between AD 1125–1150 and subsequent abandonment. The condition of the remains suggest that there may have been cannibalism, an extremely rare phenomenon in Ancient Pueblo People's history. Since it is such a rare occurrence, it is difficult to postulate the reasons for the violence. The attacks could have resulted from starvation during a period of drought or because Chuskans were seen as outsiders to the area.[12]

Culture and religion

- The People. The ancient people were short in stature, men were an average of about 5 feet and 4 inches tall and women were a few inches shorter. Women often died between the ages of 20 and 25. Men generally lived to 31 or 35 years old. By the age of 29, many people had degenerative arthritis. People rarely lived more than 40 years.[14]

- Based upon the similarities between the Ancient Pueblo Peoples and modern puebloan people, it is likely that the communities were organized in clans, or groups of related family members, by matrilineal lines of descent. When a couple married, they lived at the home of the wife's mother and the husband engaged in religious activities in the kiva of his mother's clan.[15]

- During the Pueblo III period some people were buried with personal objects, indicating both a level of prestige and evolved religious beliefs. To have earned a higher status within the community infers that the settlements developed hierarchical political and social systems.[4]

- Religious devotion. The number of individual family and "great" kivas, ceremonial objects, and elaborate altars are indicative of a rich and dedicated spiritual life.[9] Kivas, generally men's domain, were used for religious rituals, social activity and weaving. They were generally constructed below the surface of the ground with: a fire pit, overhead entry, spirit entrance or Sipapu, banquette seating and a ventilator shaft. Sometimes adjacent kivas were connected by tunnels. "Great" kivas were constructed for larger community activities. Painted images of men, plants, animals and designs were painted in some kivas, such as the Fire Temple at Mesa Verde. The Fire Temple designs are similar to the ceremonial rooms of the modern Hopi people, specifically the "New Fire" rituals.[16]

- It is likely that public ceremonial dances were performed for bountiful harvests, health, hunting and rain, like the Hopi Snake Dance. Whatever the ceremonial observance, each person had a role which increased in responsibility and status over time.[17]

- Wall art. Carved petroglyphs and painted pictographs are also found in the cliffs, buildings and boulders of the pueblo society. The designs were often of animals, people, plants and geometric images.[18] Hovenweep National Monument had two superior kiva wall murals of the Pueblo III era which are now conserved at the Anasazi Heritage Center.[12]

Agriculture

As a means to improve agricultural yield, the Pueblo III period saw advancements in water conservation. Stones were placed in and around farm land to divert flow for irrigation, water conservation and to reduce run-off. This was accomplished through the use of bordered gardens, reservoirs, check dams and terraced gardening plots - building upon the techniques of the Pueblo II Era.[4][19][20] Corn, beans and squash were cultivated using dryland farming techniques. Their diet was supplemented with wild plants, such as beeweed. As nutrients were depleted from over-farming, new land was found and cleared for cultivation.[21]

Pottery

Corrugated gray ware and decorated black-on-white pottery were prevalent in the beginning of the era. Gray pottery vessels were used for cooking and storage. Designs, primarily geometric designs and symbols of people, animals and birds, were painted on the exterior of black-on-white pottery and the interior of bowls. The pottery made included cooking vessels, jars, mugs, bowls, pitchers, and ladles.[22][23] Pottery making became an art form for individuals who specialized in distinctive styles made for trade. Polychrome (multiple colored) pottery painted in white, orange, red and black was made at the end of the Pueblo III period.[4]

Due to the considerable refinements during this period, pottery from Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon are considered "some of the world's finest ceramic art, ancient or modern."[9]

Other material goods

Some of the material goods from this period are:

- Stone tools. Men gathered hard stone from mountains, river beds or nearby boulders for stone tools:

- axes for cutting down trees

- hammerstones for shaping sandstone blocks

- projectile points for bow and arrow hunting

- knives to cut plants and animal hides

- manos and metates for grinding corn, plants, nuts and seeds.[24]

- Bone tools. Deer, sheep, rabbit and other animal bones were also shaped for tools, such as stitching awls for making clothing, working hides and weaving. Bones were also used for scrapers and fleshers.[24]

- Yucca, a regionally bountiful, drought-resistant plant, was used to make many household goods. Its fibers were used for sewing, cordage and woven into blankets, clothing, sandals and baskets. Sharp barbs were used as needles or made into paint brushes. It was also used as soap and a source of food.[25]

- Cotton cloth. Cotton was obtained through trading, dyed and woven into material by men for clothing.[19]

- Stone and shell ornaments. Jewellery and other ornaments were made from bartered shells and stones from the coasts of Mexico and California. Within the region, turquoise, soapstone and lignite were attained through trade.[26] Just as pottery from this period has received world-wide recognition, shell and turquoise-inlay work from this period was noteworthy for its artisanry.[9]

- Other items obtained through trade. Aside from cotton, shell and stones, the people of the third Pueblo period could also barter for cloth, salt, and pottery.[26]

Great migration

By 1300 Ancient Pueblo People from the Four Corners region abandoned their settlements. The migration was likely as the result of prolonged drought from AD 1276 to 1299 which would have caused considerable hardship, such as starvation, raids from neighboring starving people, and dramatic reduction in the pueblo population. During and after the drought there was a mass exodus south to central and southern Arizona and New Mexico.[1][4][27]

There are other theories about why people forever abandoned the northern pueblo regions. Soil nutrients may have become depleted due to many years of farming. Or there may have been wars with other regional tribes.[28]

Cultural groups and periods

The cultural groups of this period include:[29]

- Anasazi - southern Utah, southern Colorado, northern Arizona and northern and central New Mexico.

- Hohokam - southern Arizona.

- Mogollon - southeastern Arizona, southern New Mexico and northern Mexico.

- Patayan - western Arizona, California and Baja California.

Notable Pueblo III sites

Gallery

-

White House ruins in Canyon de Chelly National Monument

-

Keet Seel cliff dwellings at Navajo National Monument

-

Overhead view of Square Tower House at Mesa Verde National Park

-

Nankoweap ruins, Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona

-

Cliffs at Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico

-

Houses at Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico

-

Interior of cliff dwellings at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument

-

Monarch Cave Ruin at Comb Ridge, Utah

-

Lowry Pueblo in southwestern Colorado

-

Hovenweep Castle at Hovenweep National Monument

-

Moon House on Cedar Mesa in Utah

-

![Large square map of northwestern New Mexico and neighboring parts of, clockwise from left, western Arizona, southeastern Utah, and southwestern Colorado. The map region has a green and blocky rectangular-crescent area at its center labeled "Chaco Culture National Historical Park". Radiating from the green region are seven segmented gold lines: "[p]rehistoric roads", each several dozen kilometers in length when measured according to the map scale factor. Roughly seventy red dots mark the location of "Great House[s]"; they are widely spread across the map, many of them far from the green area, near the extremes of the map, more than one hundred kilometers from the green area. Two proceed roughly south, one southwest, one northwest, one straight north, and the last to the southeast. Yellow dots mark the location of modern settlements: "Shiprock", "Cortez", "Farmington", and "Aztec" to the northwest and north; "Nageezi", "Cuba", and "Pueblo Pintado" to the northeast and east; "Grants", "Crownpoint", and "Gallup" to the south and southwest. They are connected by a network of gray lines marking various interstate and state highways. A fan of thin blue lines along the northern margins of the map depict the San Juan River and its communicants.](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/P/r/e/h/Prehistoric-Roads.jpg)

Prehistoric roads and Great Houses in the San Juan Basin, superimposed on a map showing modern roads and settlements.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Pueblo III - Overview. Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. 2011. Retrieved 10-11-2011.

- ↑ Kayenta Region. Manitou Cliff Dwellings Museum. Retrieved 10-13-2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Kantner, John (2004). "Ancient Puebloan Southwest", pp. 161-66

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Ancestral Pueblo - Pueblo III. Anthropology Laboratories of the Northern Arizona University. Retrieved 10-12-2011.

- ↑ Lekson, pp. 158, 175-180.

- ↑ Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. pp. 47-56. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ↑ Talus House. Bandelier National Monument, National Park Service. Retrieved 10-15-2011.

- ↑ Main Loop Trail Stop 11. Bandelier National Monument, National Park Service. Retrieved 10-15-2011.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Great Pueblo Period. Bandelier National Monument, National Park Service. Retrieved 10-14-2011.

- ↑ Life of the Early People at Bandelier: Shelter. Bandelier National Monument, National Park Service. Retrieved 10-15-2011.

- ↑ Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. pp. 13, 47-59. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Hurley, Warren F. X. (2000). A Retrospective on the Four Corners Archeological Program. National Park Service. Page 3. Retrieved 10-15-2011.

- ↑ Fagan, Brian Murray. (2005). Chaco Canyon: Archaeologists Explore the Lives of an Ancient Society. Oxford University Press. May 1, 2005. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-19-517043-6.

- ↑ Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. p. 71. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ↑ Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. pp. 60-62. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ↑ Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. pp. 60-62, 72. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ↑ Life of the Early People at Bandelier: Religion. Bandelier National Monument, National Park Service. Retrieved 10-15-2011.

- ↑ Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. p. 72. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Ancestral Puebloan Chronology (teaching aid). Mesa Verde National Park, National Park Service. Retrieved 10-16-2011.

- ↑ Reed, Paul F. (2000) Foundations of Anasazi Culture: The Basketmaker Pueblo Transition. University of Utah Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-87480-656-9.

- ↑ Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. pp. 64-65. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ↑ Pueblo Indian History. Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. Retrieved 10-11-2011.

- ↑ Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. p. 66. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. p. 67. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ↑ Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. p. 70. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. p. 68-69. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ↑ Droughts and Migrations. Bandelier National Monument, National Park Service. Retrieved 10-14-2011.

- ↑ The Ancient Ones. Frontier in Transition: A History of Southwestern Colorado. Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved 10-16-2011.

- ↑ Gibbon, Guy E.; Ames, Kenneth M. (1998) Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 14, 408. ISBN 0-8153-0725-X.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||