Puck (magazine)

Puck was America's first successful humor magazine of colorful cartoons, caricatures and political satire of the issues of the day. It was published from 1871 until 1918.

History

The weekly magazine was founded by Joseph Ferdinand Keppler in St. Louis. It began publishing English and German language editions in March 1871. Five years later, the German edition of Puck moved to New York City, where the first magazine was published on September 27, 1876. The English language edition soon followed on March 14, 1877.

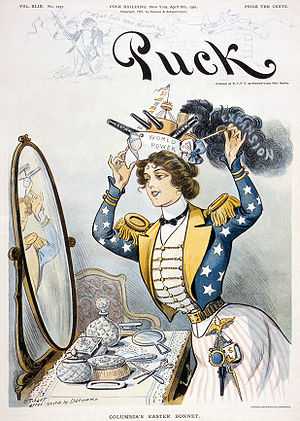

The English language magazine continued in operation for more than 40 years under several owners and editors until it was bought by the William Randolph Hearst company in 1916. The publication lasted two more years; the final edition was distributed September 5, 1918. A typical 32-page issue contained a full-color political cartoon on the front cover and a color non-political cartoon or comic strip on the back cover. There was always a double-page color centerfold, usually on a political topic. There were numerous black-and-white cartoons used to illustrate humorous anecdotes. A page of editorials commented on the issues of the day, and the last few pages were devoted to advertisements.

"Puckish" means "childishly mischievous". This led Shakespeare's Puck character (from A Midsummer Night's Dream) to be recast as a charming near-naked boy and used as the title of the magazine. Puck was the first magazine to carry illustrated advertising and the first to successfully adopt full-color lithography printing for a weekly publication. The magazine consisted of 16 pages measuring 10 inches by 13.5 inches with front and back covers in color and a color double-page centerfold. The cover always quoted Puck saying, "What fools these mortals be!" The jaunty symbol of Puck is conceived as a putto in a top hat who admires himself in a hand-mirror. He appears not only on the magazine covers but over the entrance to the Puck Building in New York's Nolita neighborhood, where the magazine was published, as well.

In May 1893, Puck Press published A Selection of Cartoons from Puck by Joseph Keppler (1877–1892) featuring 56 cartoons chosen by Keppler as his best work. Also during 1893, Keppler temporarily moved to Chicago and published a smaller-format, 12-page version of Puck from the Chicago World's Fair grounds. Shortly thereafter, Joseph Keppler died, and Henry Cuyler Bunner, editor of Puck since 1877 continued the magazine until his own death in 1896. Harry Leon Wilson replaced Bunner and remained editor until he resigned in 1902.[1] Joseph Keppler, Jr. then became the editor.

Distinguished contributors

Over the years, Puck employed many early cartoonists of note, including, Louis Dalrymple, Bernhard Gillam, Livingston Hopkins, Frederick Burr Opper, Louis Glackens, Albert Levering, Frank Nankivell, J.S. Pughe, Rose O'Neill, Charles Taylor, James Albert Wales and Eugene Zimmerman.

Politics and religion

An 1890 Puck cartoon depicts President Benjamin Harrison at his desk wearing his grandfather's hat which is too big for his head, suggesting that he is not fit for the presidency. Atop a bust of William Henry Harrison, a raven with the head of Secretary of State James G. Blaine gawks down at the President, a reference to the famous Edgar Allan Poe poem "The Raven". Blaine and Harrison were both at odds over the recently proposed McKinley Tariff.

Politically it sided with the Bourbon Democrats, whose hero was Grover Cleveland. It favored German Americans and victimised Irish Americans.

As Thomas (2004) explains:

- [I]n an age of partisan politics and partisan journalism, Puck became the nation's premier journal of graphic humor and political satire, played an important role as a non-partisan crusader for good government and the triumph of American constitutional ideals. Its prime targets, however, were not just corrupt machine politicians. The magazine included as well what it, like the letterpress, condemned as the nefarious political agenda of the Catholic Church, especially its new Pope, Leo XIII. Indeed, New York's infamous Irish Tammany Hall, committed to spoils and patronage as the means of dominating the body politic, was all the more dangerous to Puck because, beginning in the 1870s, Irish Catholics dominated it. The hall's Irish Catholic base enabled the magazine to rationalize more completely its conviction that the Catholic Church, ruled by a foreign potentate dressed in the irrational garb of infallibility, was a menace not only to the nation's body politic but also to its democratic soul. If allowed to proceed unimpeded, the pope and his minions, along with Tammany's bosses and supporters, would convert the nation into their personal fiefdom. Puck was not about to let that happen. In cartoons and editorials spanning two decades, the magazine blasted and often conjoined both Tammany and the papacy with invidious comparisons that left few readers in doubt as to their complicity.

Puck Building

Puck was housed from 1887 in the landmark Chicago-style Romanesque Revival Puck Building at Lafayette and Houston Streets, New York City. The steel-frame building was designed by architects Albert and Herman Wagner in 1885, as the world's largest lithographic pressworks under a single roof, with its own electricity-generating dynamo. It takes up a full block on Houston Street, bounded by Lafayette and Mulberry Streets.

Mad (once located two blocks away at 225 Lafayette Street) parodied Puck's motto as "What food these morsels be!"

London edition

A London edition of Puck was published between January 1889 and June 1890. Amongst contributors was the English cartoonist and political satirist Tom Merry.[2]

Sources

- Richard Samuel West, Satire On Stone, University of Illinois Press, 1988, ISBN 0-252-01497-9

- Samuel J. Thomas, "Mugwump Cartoonists, the Papacy, and Tammany Hall in America's Gilded Age" Religion and American Culture Summer 2004, Vol. 14, No. 2, Pages 213–250

- ↑ "Guide to the Harry Leon Wilson Papers, ca. 1879–1939". Berkeley, California: Bancroft Library. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ↑ Simon Houfe, Dictionary of British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists 1800–1914 (1978)

Puck cartoons

-

Nasty little printer's devils, 1888

-

"The Infant Hercules and the Standard Oil serpents", May 23, 1906 issue; depicting U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt "grabbing the head of Nelson W. Aldrich and the snake-like body of John D. Rockefeller".

-

Emoticons, 1881

-

European Royalties – Go West! (after assassination of Alexander II of Russia) 1881

-

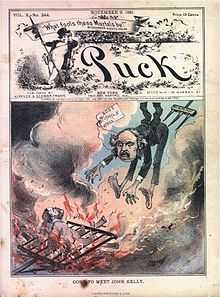

"Gone to meet John Kelly", figure identified as "Boss McLaughlin" (Hugh McLaughlin, a political boss), November 9, 1881 cover

-

German edition: Monopoly Millionaires Dividing the Country (William Henry Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, Cyrus West Field and two more)

-

July 6, 1881: President James A. Garfield, auf seinem Posten gefällt

-

c. 1878: Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz accosts U.S. Representative James G. Blaine chopping a tree in the forest

-

Cyclone as metaphor for political revolution (election of 1894)

-

"Paris in half-mourning" by Ralph Barton, 1915.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Puck (magazine). |

External links

- Complete text 1884 issues

- Complete text 1880 issues

- Gallery of 1877 Puck Magazine caricatures by Joseph Keppler

- Puck's Role in Gilded Age Politics from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- Cartoons from Puck featuring U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

- Cartoon from Puck featuring Oscar Wilde as the apostle of aestheticism, 1882