Proverb

A proverb (from Latin: proverbium) is a simple and concrete saying, popularly known and repeated, that expresses a truth based on common sense or the practical experience of humanity. They are often metaphorical. A proverb that describes a basic rule of conduct may also be known as a maxim.

Proverbs are often borrowed from similar languages and cultures, and sometimes come down to the present through more than one language. Both the Bible (including, but not limited to the Book of Proverbs) and medieval Latin (aided by the work of Erasmus) have played a considerable role in distributing proverbs across Europe. Mieder has concluded that cultures that treat the Bible as their "major spiritual book contain between three hundred and five hundred proverbs that stem from the Bible."[1] However, almost every culture has examples of its own unique proverbs.

Examples

- Haste makes waste

- A stitch in time saves nine

- Ignorance is bliss

- Mustn't cry over spilled milk.

- You can catch more flies with honey than you can with vinegar.

- You can lead a horse to water, but you can't make him drink.

- Those who live in glass houses shouldn't throw stones.

- A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

- Everyone unto their own.

- Well begun is half done.

- A little learning is a dangerous thing.

- A rolling stone gathers no moss.

- It is better to be smarter than you appear than to appear smarter than you are.

- Good things come to those who wait.

- A poor workman blames his tools.

- A dog is a man's best friend.

- An apple a day keeps the doctor away.

- If the shoe fits, wear it!

- Honesty is the best policy

- Slow and steady wins the race

Paremiology

The study of proverbs is called paremiology (from Greek παροιμία - paroimía, "proverb, maxim, saw"[2]) and can be dated back as far as Aristotle. Paremiography, on the other hand, is the collection of proverbs. A prominent proverb scholar in the United States is Wolfgang Mieder. He has written or edited over 50 books on the subject, edits the journal Proverbium, has written innumerable articles on proverbs, and is very widely cited by other proverb scholars. Mieder defines the term proverb as follows:

A proverb is a short, generally known sentence of the folk which contains wisdom, truth, morals, and traditional views in a metaphorical, fixed and memorizable form and which is handed down from generation to generation.—Mieder 1985:119; also in Mieder 1993:24

Sub-genres include proverbial comparisons (“as busy as a bee”) and proverbial interrogatives (“Does a chicken have lips?”) .

Another subcategory is wellerisms, named after Sam Weller from Charles Dickens's The Pickwick Papers (1837). They are constructed in a triadic manner which consists of a statement (often a proverb), an identification of a speaker (person or animal), and a phrase that places the statement into an unexpected situation. Ex.: “Every evil is followed by some good,” as the man said when his wife died the day after he became bankrupt.

Yet another category of proverb is the anti-proverb (Mieder and Litovkina 2002), also called Perverb. In such cases, people twist familiar proverbs to change the meaning. Sometimes the result is merely humorous, but the most spectacular examples result in the opposite meaning of the standard proverb. Examples include, "Nerds of a feather flock together", "Early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy, and likely to talk about it," and "Absence makes the heart grow wander". Anti-proverbs are common on T-shirts, such as "If at first you don't succeed, skydiving is not for you."[3] Even classic Latin proverbs can be remolded as anti-proverbs, such as "Carpe noctem" and "Carpe per diem".

A similar form is proverbial expressions (“to bite the dust”). The difference is that proverbs are unchangeable sentences, while proverbial expressions permit alterations to fit the grammar of the context.[4]

Another close construction is an allusion to a proverb, such as "The new boss will probably fire some of the old staff, you know what they say about a 'new broom'," alluding to the proverb "The new broom will sweep clean."[4]

Typical stylistic features of proverbs (as Shirley Arora points out in her article, The Perception of Proverbiality (1984)) are:

- Alliteration[5] (Forgive and forget)

- Parallelism (Nothing ventured, nothing gained)

- Rhyme (When the cat is away, the mice will play)

- Ellipsis (Once bitten, twice shy)

In some languages, assonance, the repetition of a vowel, is also exploited in forming artistic proverbs, such as the following extreme example from Oromo, of Ethiopia.

- kan mana baala, a’laa gaala (“A leaf at home, but a camel elsewhere"; somebody who has a big reputation among those who do not know him well.)

Similarly, from Tajik:

- Az yak palak ― chand handalak ("From one vine, many different melons.")

Notice that in both of these cases of complete assonance, the vowel is <a>, the most common vowel in human languages.

Also in Amharic, complete assonance is not infrequent when verbs are in the 3rd person masculine singular, past tense.

- yälämmänä mänämmänä - (The one who begs becomes thin.)

Internal features that can be found quite frequently include:

- Hyperbole (All is fair in love and war)

- Paradox (For there to be peace there must first be war)

- Personification (Hunger is the best cook)

To make the respective statement more general most proverbs are based on a metaphor. Further typical features of the proverb are its shortness and the fact that its author is generally unknown.

In the article “Tensions in Proverbs: More Light on International Understanding,” Joseph Raymond comments on what common Russian proverbs from the 18th and 19th centuries portray: Potent antiauthoritarian proverbs reflected tensions between the Russian people and the Czar. The rollickingly malicious undertone of these folk verbalizations constitutes what might be labeled a ‘paremiological revolt.’ To avoid openly criticizing a given authority or cultural pattern, folk take recourse to proverbial expressions which voice personal tensions in a tone of generalized consent. Thus, personal involvement is linked with public opinion[6] Proverbs that speak to the political disgruntlement include: “When the Czar spits into the soup dish, it fairly bursts with pride”; “If the Czar be a rhymester, woe be to the poets”; and “The hen of the Czarina herself does not lay swan’s eggs.” While none of these proverbs state directly, “I hate the Czar and detest my situation” (which would have been incredibly dangerous), they do get their points across.

Proverbs are found in many parts of the world, but some areas seem to have richer stores of proverbs than others (such as West Africa), while others have hardly any (North and South America) (Mieder 2004b:108,109).

Proverbs are used by speakers for a variety of purposes. Sometimes they are used as a way of saying something gently, in a veiled way (Obeng 1996). Other times, they are used to carry more weight in a discussion, a weak person is able to enlist the tradition of the ancestors to support his position, or even to argue a legal case.[7] Proverbs can also be used to simply make a conversation/discussion more lively. In many parts of the world, the use of proverbs is a mark of being a good orator.

The study of proverbs has application in a number of fields. Clearly, those who study folklore and literature are interested in them, but scholars from a variety of fields have found ways to profitably incorporate the study proverbs. For example, they have been used to study abstract reasoning of children, acculturation of immigrants, intelligence, the differing mental processes in mental illness, cultural themes, etc. Proverbs have also been incorporated into the strategies of social workers, teachers, preachers, and even politicians. (For the deliberate use of proverbs as a propaganda tool by Nazis, see Mieder 1982.)

There are collections of sayings that offer instructions on how to play certain games, such as dominoes (Borajo et al. 1990) and the Oriental board game go (Mitchell 2001). However, these are not prototypical proverbs in that their application is limited to one domain.

One of the most important developments in the study of proverbs (as in folklore scholarship more generally) was the shift to more ethnographic approaches in the 1960s. This approach attempted to explain proverb use in relation to the context of a speech event, rather than only in terms of the content and meaning of the proverb.[8]

Another important development in scholarship on proverbs has been applying methods from cognitive science to understand the uses and effects of proverbs and proverbial metaphors in social relations.[9]

Definitions of "proverb"

Defining a “proverb” is a difficult task. Proverb scholars often quote Archer Taylor’s classic “The definition of a proverb is too difficult to repay the undertaking... An incommunicable quality tells us this sentence is proverbial and that one is not. Hence no definition will enable us to identify positively a sentence as proverbial”.[10] Another common definition is from Lord John Russell (c. 1850) “A proverb is the wit of one, and the wisdom of many.” [11]

More constructively, Mieder has proposed the following definition, “A proverb is a short, genrally known sentence of the folk which contains wisdom, truth, morals, and traditional views in a metaphorical, fixed, and memorizable form and which is handed down from generation to generation.”[12] Norrick created a table of distinguishing features to distinguish proverbs from idioms, cliches, etc.[13] Prahlad distinguishes proverbs from some other, closely related types of sayings, “True proverbs must further be distinguished from other types of proverbial speech, e.g. proverbial phrases, Wellerisms, maxims, quotations, and proverbial comparisons.”[14]

There are many sayings in English that are commonly referred to as “proverbs”, such as weather sayings. Alan Dundes, however, rejects including such sayings among truly proverbs: “Are weather proverbs proverbs? I would say emphatically 'No!'”[15] The definition of “proverb” has also changed over the years. For example, the following was labeled “A Yorkshire proverb” in 1883, but would not be categorized as a proverb by most today, “as throng as Throp's wife when she hanged herself with a dish-cloth.”[16] The changing of the definition of "proverb" is also noted in Turkish.[17]

In other languages and cultures, the definition of “proverb” also differs from English. In the Chumburung language of Ghana, "aŋase are literal proverb and akpare are metaphoric ones.”[18] Among the Bini of Nigeria, there are three words that are used to translate "proverb": ere, ivbe, and itan. The first relates to historical events, the second relates to current events, and the third was “linguistic ornamentation in formal discourse”.[19] Among the Balochi of Pakistan and Afghanistan, there is a word batal for ordinary proverbs and bassīttuks for "proverbs with background stories".[20]

All of this makes it difficult to come up with a definition of "proverb" that is universally applicable, which brings us back to Taylor's observation, "An incommunicable quality tells us this sentence is proverbial and that one is not.".

Grammatical structures of proverbs

Proverbs in various languages are found with a wide variety of grammatical structures.[21] In English, for example, we find the following structures (in addition to others):

- Imperative, negative - Don't beat a dead horse.

- Imperative, positive - Look before you leap.

- Parallel phrases - Garbage in, garbage out.

- Rhetorical question - Is the Pope Catholic?

- Declarative sentence - Birds of a feather flock together.

However, people will often quote only a fraction of a proverb to invoke an entire proverb, e.g. "All is fair" instead of "All is fair in love and war", and "A rolling stone" for "A rolling stone gathers no moss."

The grammar of proverbs is not always the typical grammar of the spoken language, often elements are moved around, to achieve rhyme or focus.[22]

Use in conversation

Proverbs are used in conversation by adults more than children, partially because adults have learned more proverbs than children. Also, using proverbs well is a skill that is developed over years. Additionally, children have not mastered the patterns of metaphorical expression that are invoked in proverb use. Proverbs, because they are indirect, allow a speaker to disagree or give advice in a way that may be less offensive. Studying actual proverb use in conversation, however, is difficult since the researcher must wait for proverbs to happen.[23] An Ethiopian researcher, Tadesse Jaleta Jirata, made headway in such research by attending and taking notes at events where he knew proverbs were expected to be part of the conversations.[24]

Use in literature

Many authors have used proverbs in their writings. Probably the most famous user of proverbs in novels is J. R. R. Tolkien in his The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings series.[25][26] Also, C. S. Lewis created a dozen proverbs in The Horse and His Boy.[27] These books are notable for not only using proverbs as integral to the development of the characters and the story line, but also for creating proverbs.

Among medieval literary texts, Geoffrey Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde plays a special role because Chaucer's usage seems to challenge the truth value of proverbs by exposing their epistemological unreliability.[28]

Proverbs have been the inspiration for titles of books: The Bigger they Come by Erle Stanley Gardner and Birds of a Feather (several books with this title). Some stories have been written with a proverb overtly as an opening, such as "A stitch in time saves nine" at the beginning of "Kitty's Class Day", one of Louisa May Alcott's Proverb Stories. Other times, a proverb appears at the end of a story, summing up a moral to the story, frequently found in Aesop's Fables, such as "Heaven helps those who help themselves" from Hercules and the Wagoner.

Proverbs have also been used strategically by poets.[29] Sometimes proverbs (or portions of them or anti-proverbs) are used for titles, such as "A bird in the bush" by Lord Kennet and his stepson Peter Scott and "The blind leading the blind" by Lisa Mueller. Sometimes, multiple proverbs are important parts of poems, such as Paul Muldoon's "Symposium", which begins "You can lead a horse to water but you can't make it hold its nose to the grindstone and hunt with the hounds. Every dog has a stitch in time..."

Some authors have bent and twisted proverbs, creating anti-proverbs, for a vartiety of literary effects. For example, in the Harry Potter novels, J. K. Rowling reshapes a standard English proverb into “It’s no good crying over spilt potion” and Dumbledore advises Harry not to “count your owls before they are delivered”.[30] In a slightly different use of reshaping proverbs, in the Aubrey–Maturin series of historical naval novels by Patrick O'Brian, Capt. Jack Aubrey humorously mangles and mis-splices proverbs, such as “Never count the bear’s skin before it is hatched” and “There’s a good deal to be said for making hay while the iron is hot.”[31]

Because proverbs are so much a part of the language and culture, authors have sometimes used proverbs in historical fiction effectively, but anachronistically, before the proverb was actually known. For example, the novel Ramage and the Rebels, by Dudley Pope is set in approximately 1800. Captain Ramage reminds his adversary "You are supposed to know that it is dangerous to change horses in midstream" (p. 259), with another allusion to the same proverb three pages later. However, the proverb about changing horses in midstream is reliably dated to 1864,[32] so the proverb could not have been known or used by a character from that period.

Some authors have used so many proverbs that there have been entire books written cataloging their proverb usage, such as Charles Dickens,[33] Agatha Christie,[34] and George Bernard Shaw.[35]

On the non-fiction side, proverbs have also been used by authors. Some have been used as the basis for book titles, e.g. I Shop, Therefore I Am: Compulsive Buying and the Search for Self by April Lane Benson. Some proverbs been used as the basis for article titles, "All our eggs in a broken basket: How the Human Terrain System is undermining sustainable military cultural competence."[36] Many authors have cited proverbs as epigrams at the beginning of their articles, e.g. "'If you want to dismantle a hedge, remove one thorn at a time' Somali proverb" in an article on peacemaking in Somalia.[37]

Interpretations of proverbs

Interpreting proverbs is often complex. Interpreting proverbs from other cultures is much more difficult than interpreting proverbs in ones own culture. Even within English-speaking cultures, there is difference of opinion on how to interpret the proverb A rolling stone gathers no moss. Some see it as condemning a person that keeps moving, seeing moss as a positive things, such as profit; others see it the proverb as praising people that keep moving and developing, seeing moss as a negative thing, such as negative habits.

In an extreme example, one researcher working in Ghana found that for a single Akan proverb, twelve different interpretations were given.[38] Though this is extreme, proverbs can often have multiple interpretations.

Children will sometimes interpret proverbs in a literal sense, not yet knowing how to understand the conventionalized metaphor. Interpretation of proverbs is also affected by injuries and diseases of the brain, "A hallmark of schizophrenia is impaired proverb interpretation."[39]

Counter proverbs

There are often proverbs that contradict each other, such as "Look before you leap" and "He who hesitates is lost." These have been labeled "counter proverbs" [40] When there are such counter proverbs, each can be used in its own appropriate situation, and neither is intended to be a universal truth.

The concept of "counter proverb" is more about pairs of contradictory proverbs than about the use of proverbs to counter each other in an argument. For example, the following pair are counter proverbs from Ghana "It is the patient person who will milk a barren cow" and "The person who would milk a barren cow must prepare for a kick on the forehead" [41] The two contradict each other, whether they are used in an argument or not (though indeed they were used in an argument). But the same work contains an appendix with many examples of proverbs used in arguing for contrary positions, but proverbs that are not inherently contradictory, (pp. 157–171), such as "One is better off with hope of a cow's return than news of its death" countered by "If you don't know a goat [before its death] you mock at its skin". Though this pair was used in a contradictory way in a conversation, they are not a set of "counter proverbs".

"Counter proverbs" are not the same as a "paradoxical proverb", a proverb that contains a seeming paradox.[42]

Proverbs in drama and film

Similarly to other forms of literature, proverbs have also been used as important units of language in drama and films. This is true from the days of classical Greek works[43] to old French [44] to Shakespeare[45] to today. The use of proverbs in drama and film today is found in languages around the world, such as Yorùbá.[46]

A film that makes rich use of proverbs is Forrest Gump, known for both using and creating proverbs.[47][48] Other studies of the use of proverbs in film include work by Kevin McKenna on the Russian film Aleksandr Nevsky,[49] Haase's study of an adaptation of Little Red Riding Hood,[50] and Elias Dominguez Barajas on the film Viva Zapata!.[51]

In the case of Forrest Gump, the screenplay by Eric Roth had more proverbs than the novel by Winston Groom, but for The Harder They Come, the reverse is true, where the novel derived from the movie by Michael Thelwell has many more proverbs than the movie.[52]

Éric Rohmer, the French film director, directed a series of films, the "Comedies and Proverbs", where each film was based on a proverb: The Aviator's Wife, The Perfect Marriage, Pauline at the Beach, Full Moon in Paris (the film's proverb was invented by Rohmer himself: "The one who has two wives loses his soul, the one who has two houses loses his mind."), The Green Ray, Boyfriends and Girlfriends.[53]

Movie titles based on proverbs include Murder Will Out (1939 film), Try, Try Again, and The Harder They Fall. The title of an award-winning Turkish film, Three Monkeys, also invokes a proverb, though the title does not fully quote it.

They have also been used as the titles of plays: Baby with the Bathwater by Christopher Durang, Dog Eat Dog by Mary Gallagher, and The Dog in the Manger by Charles Hale Hoyt. Proverbs have also been used in musical dramas, such as The Full Monty, which has been shown to use proverbs in clever ways.[54]

Proverbs and music

Proverbs are often poetic in and of themselves, making them ideally suited for adapting into songs. Proverbs have been used in music from opera to country to hip-hop. Proverbs have also been used in music in other languages, such as the Akan language[55] and the Igede language.[56]

English examples of using proverbs in music include Elvis Presley's Easy come, easy go, Harold Robe's Never swap horses when you're crossing a stream, Arthur Gillespie's Absence makes the heart grow fonder, Bob Dylan's Like a rolling stone, Cher's Apples don't fall far from the tree. Lynn Anderson made famous a song full of proverbs, I never promised you a rose garden (written by Joe South). In choral music, we find Michael Torke's Proverbs for female voice and ensemble. A number of Blues musicians have also used proverbs extensively.,[57][58] The frequent use of proverbs in Country music has led to published studies of proverbs in this genre.,[59][60] The Reggae artist Jahdan Blakkamoore has recorded a piece titled Proverbs Remix. The opera Maldobrìe contains careful use of proverbs.[61] An extreme example of many proverbs used in composing songs include Bruce Springsteen performed a song almost entirely composed of proverbs.[62] The Mighty Diamonds recorded a song called simply "Proverbs".

The band Fleet Foxes used the proverb painting Netherlandish Proverbs for the cover of their eponymous album Fleet Foxes.

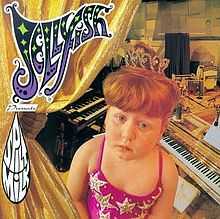

In addition to proverbs being used in songs themselves, some rock bands have used parts of proverbs as their names, such as the Rolling Stones, Bad Company, Mothers of Invention, Feast or Famine, Of Mice and Men. There have been at least two groups that called themselves "The Proverbs". In addition, many albums have been named with allusions to proverbs, such as Spilt milk (a title used by Jellyfish and also Kristina Train), The more things change by Machine Head, Silk purse by Linda Rondstadt, Another day, another dollar by DJ Scream Roccett, The blind leading the naked by Vicious Femmes, What's good for the goose is good for the gander by Bobby Rush, Resistance is Futile by Steve Coleman, Murder will out by Fan the Fury. The proverb Feast or famine has been used as an album title by Chuck Ragan, Reef the Lost Cauze, Indiginus, and DaVinci. The band Splinter Group released an album titled When in Rome, Eat Lions. The band Downcount used a proverb for the name of their tour, Come and take it.

Sources of proverbs

Proverbs come from a variety of sources. Some are, indeed, the result of people pondering and crafting language, such as some by Confucius, Plato, Baltasar Gracián, etc. Others are taken from such diverse sources as poetry,[63] songs, commercials, advertisements, movies, literature, etc.[64] A number of the well known sayings of Jesus, Shakespeare, and others have become proverbs, though they were original at the time of their creation, and many of these sayings were not seen as proverbs when they were first coined. Many proverbs are also based on stories, often the end of a story. For example, the proverb "Who will bell the cat?" is from the end of a story about the mice planning how to be safe from the cat.

Though many proverbs are ancient, they were all newly created at some point by somebody. Sometimes it is easy to detect that a proverb is newly coined by a reference to something recent, such as the Haitian proverb "The fish that is being microwaved doesn't fear the lightning".[65] Also, there is a proverb in the Kafa language of Ethiopia that refers to the forced military conscription of the 1980s, "...the one who hid himself lived to have children."[66] A Mongolian proverb also shows evidence of recent origin, "A beggar who sits on gold; Foam rubber piled on edge."[67] Over 1,400 new English proverbs are said to have been coined in the 20th century.[68] This process of creating proverbs is always ongoing, so that possible new proverbs are being created constantly. Those sayings that are adopted and used by an adequate number of people become proverbs in that society.

Paremiological minimum

Grigorii Permjakov[69] developed the concept of the core set of proverbs that full members of society know, what he called the "paremiological minimum" (1979). For example, an adult American is expected to be familiar with "Birds of a feather flock together", part of the American paremiological minimum. However, an average adult American is not expected to know "Fair in the cradle, foul in the saddle", an old English proverb that is not part of the current American paremiological minimum. Thinking more widely than merely proverbs, Permjakov observed "every adult Russian language speaker (over 20 years of age) knows no fewer than 800 proverbs, proverbial expressions, popular literary quotations and other forms of cliches".[70] Studies of the paremiological minimum have been done for a limited number of languages, including Russian,[71] Hungarian,[72] Czech,[73] Somali,[74] Nepali,[75] Gujarati,[76] Spanish,[77] and Esperanto.[78] Two noted examples of attempts to establish a paremiological minimum in America are by Haas (2008) and Hirsch, Kett, and Trefil (1988), the latter more prescriptive than descriptive.

Proverbs in visual form

From ancient times, people around the world have recorded proverbs in visual form. This has been done in two ways. First, proverbs have been written to be displayed, often in a decorative manner, such as on pottery, cross-stitch, murals,[79][80] kangas (East African women's wraps),[81] and quilts.[82]

Secondly, proverbs have often been visually depicted in a variety of media, including paintings, etchings, and sculpture. Jakob Jordaens painted a plaque with a proverb about drunkenness above a drunk man wearing a crown, titled The King Drinks. Probably the most famous examples of depicting proverbs are the different versions of the paintings Netherlandish Proverbs by the father and son Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Pieter Brueghel the Younger, the proverbial meanings of these paintings being the subject of a 2004 conference, which led to a published volume of studies (Mieder 2004a). Another famous painting depicting some proverbs and also idioms (leading to a series of additional paintings) is Proverbidioms by T. E. Breitenbach. Corey Barksdale has even produced a book of paintings with specific proverbs and pithy quotations.[83] The British artist Chris Gollon has painted a major work entitled "Big Fish Eat Little Fish", a title echoing Bruegel's painting Big Fishes Eat Little Fishes.

Sometimes well-known proverbs are pictured on objects, without a text actually quoting the proverb, such as the three wise monkeys who remind us "Hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil". When the proverb is well known, viewers are able to recognize the proverb and understand the image appropriately, but if viewers do not recognize the proverb, much of the effect of the image is lost. For example, there is a Japanese painting in the Bonsai museum in Saitama city that depicted flowers on a dead tree, but only when the curator learned the ancient (and no longer current) proverb "Flowers on a dead tree" did the curator understand the deeper meaning of the painting.[84]

A bibliography on proverbs in visual form has been prepared by Mieder and Sobieski (1999). Interpreting visual images of proverbs is subjective, but familiarity with the depicted proverb helps.[85]

In an abstract non-representational visual work, sculptor Mark di Suvero has created a sculpture titled "Proverb", which is located in Dallas, TX, near the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center.

Some artists have used proverbs and anti-proverbs for titles of their paintings, alluding to a proverb rather than picturing it. For example, Vivienne LeWitt painted a piece titled "If the shoe doesn’t fit, must we change the foot?", which shows neither foot nor shoe, but a woman counting her money as she contemplates different options when buying vegetables.[86]

Proverbs in cartoons

Cartoonists, both editorial and pure humorists, have often used proverbs, sometimes primarily building on the text, sometimes primarily on the situation visually, the best cartoons combining both. Not surprisingly, cartoonists often twist proverbs, such as visually depicting a proverb literally or twisting the text as an anti-proverb.[87] An example with all of these traits is a cartoon showing a waitress delivering two plates with worms on them, telling the customers, "Two early bird specials... here ya go."[88]

The traditional Three wise monkeys were depicted in Bizarro with different labels. Instead of the negative imperatives, the one with ears covered bore the sign “See and speak evil”, the one with eyes covered bore the sign “See and hear evil”, etc. The caption at the bottom read “The power of positive thinking.”[89] Another cartoon showed a customer in a pharmacy telling a pharmacist, “I'll have an ounce of prevention” [90] The comic strip The Argyle Sweater showed an Egyptian archeologist loading a mummy on the roof of a vehicle, refusing the offer of a rope to tie it on, with the caption “A fool and his mummy are soon parted.”[91] The comic One Big Happy showed a conversation where one person repeatedly posed part of various proverb and the other tried to complete each one, resulting in such humorous results as “Don't change horses... unless you can lift those heavy diapers.”[92]

Editorial cartoons can use proverbs to make their points with extra force as they can invoke the wisdom of society, not just the opinion of the editors.[93] In an example that invoked a proverb only visually, when a US government agency (GSA) was caught spending money extravagantly, a cartoon showed a black pot labeled “Congress” telling a black kettle labeled “GSA”, “Stop wasting the taxpayers money!”[94] It may have taken some readers a moment of pondering to understand it, but the impact of the message was the stronger for it. A German editorial cartoon linked a politician to the Nazis, showing him with a bottle of swastika-labeled wine and the caption “In vino veritas.” [95]

One cartoonist very self-consciously drew and wrote cartoons based on proverbs for the University of Vermont student newspaper The Water Tower, under the title "Proverb place".[96]

Applications of proverbs

There is a growing interest in deliberately using proverbs to achieve goals, usually to support and promote changes in society. On the negative side, this was deliberately done by the Nazis.[97] On the more positive side, proverbs have also been used for constructive purposes. For example, proverbs have been used for teaching foreign languages at various levels.[98][99] In addition, proverbs have been used for public health promotion, such as promoting breast feeding with a shawl bearing a Swahili proverb “Mother’s milk is sweet”.[100] Proverbs have also been applied for helping people manage diabetes,[101] to combat prostitution,[102] and for community development.[103]

The most active field deliberately using proverbs is Christian ministry, where Joseph G. Healey and others have deliberately worked to catalyze the collection of proverbs from smaller languages and the application of them in a wide variety of church-related ministries, resulting in publications of collections[104] and applications.[105][106] This attention to proverbs by those in Christian ministries is not new, many pioneering proverb collections having been collected and published by Christian workers.[107][108][109][110]

U.S. Navy Captain Edward Zellem pioneered the use of Afghan proverbs as a positive relationship-building tool during the war in Afghanistan, and in 2012 he published two bilingual collections of Afghan proverbs in Dari and English, part of an effort of nationbuilding.[111][112]

Borrowing and spread of proverbs

Proverbs are often and easily translated and transferred from one language into another. “There is nothing so uncertain as the derivation of proverbs, the same proverb being often found in all nations, and it is impossible to assign its paternity.”[113]

Proverbs are often borrowed across lines of language, religion, and even time. For example, a proverb of the approximate form “No flies enter a mouth that is shut” is currently found in Spain, France, Ethiopia, and many countries in between. It is embraced as a true local proverb in many places and should not be excluded in any collection of proverbs because it is shared by the neighbors. However, though it has gone through multiple languages and millennia, the proverb can be traced back to an ancient Babylonian proverb (Pritchard 1958:146).

In the Alaaba language of south central Ethiopia, there is a proverb, “The she-dog [bitch], because she is in extreme hurry gives birth to blind (ones).”[114] It is also found in Pashto language of Afghanistan.[115] Erasmus also gave a Latin form of it in his Adagia, "Canis festinans caecos parit catulos". This proverb is also well attested in ancient Greek and even Akkadian texts, where Moran gives it as “The bitch by her acting too hastily brought forth the blind”.[116] Alster, documenting an Akkadian inscription, classified this proverb as having “a longer history than any other recorded proverb in the world”, going back to “around 1800 BC”.[117]

Another example of a widely spread proverb is “A drowning person clutches at [frogs] foam”, found in Peshai of Afhganistan[118] and Orma of Kenya,[119] and presumably places in between.

Proverbs about one hand clapping are common across Asia,[120] from Dari in Afghanistan [121] to Japan.[122]

Some studies have been done devoted to the spread of proverbs in certain regions, such as India and her neighbors[123] and Europe.[124]

An extreme example of the borrowing and spread of proverbs was the work done to create a corpus of proverbs for Esperanto, where all the proverbs were translated from other languages.[125]

It is often not possible to trace the direction of borrowing a proverb between languages. This is complicated by the fact that the borrowing may have been through plural languages. In some cases, it is possible to make a strong case for discerning the direction of the borrowing based on an artistic form of the proverb in one language, but a prosaic form in another language. For example, in Ethiopia there is a proverb “Of mothers and water, there is none evil.” It is found in Amharic, Alaaba language, and Oromo, three languages of Ethiopia:

- Oromo: Hadhaa fi bishaan, hamaa hin qaban.

- Amharic: Käənnatənna wəha, kəfu yälläm.

- Alaaba" Wiihaa ʔamaataa hiilu yoosebaʔa[126]

The Oromo version uses poetic features, such as the initial ha in both clauses with the final -aa in the same word, and both clauses ending with -an. Also, both clauses are built with the vowel a in the first and last words, but the vowel i in the one syllable central word. In contrast, the Amharic and Alaaba versions of the proverb shows little evidence of sound-based art. Based on the verbal artistry of the Oromo, it appears that the Oromo form is prior to the Alaaba or Amharic, though it could be borrowed from yet another language.

Are cultural values reflected in proverbs?

There is a longstanding debate among proverb scholars as to whether the cultural values of specific language communities are reflected (to varying degree) in their proverbs. Many claim that the proverbs of a particular culture reflect the values of that specific culture, at least to some degree. Many writers have asserted that the proverbs of their cultures reflect their culture and values; this can be seen in such titles as the following: An introduction to Kasena society and culture through their proverbs,[127] Prejudice, power, and poverty in Haiti: a study of a nation's culture as seen through its proverbs,[128] Proverbiality and worldview in Maltese and Arabic proverbs,[129] Fatalistic traits in Finnish proverbs,[130] Vietnamese cultural patterns and values as expressed in proverbs,[131] and The Wisdom and Philosophy of the Gikuyu proverbs: The Kihooto worldview.[132]

However, a number of scholars argue that such claims are not valid. They have used a variety of arguments. Grauberg argues that since many proverbs are so widely circulated they are reflections of broad human experience, not any one culture's unique viewpoint.[133] Related to this line of argument, from a collection of 199 American proverbs, Jente showed that only 10 were coined in the USA, so that most of these proverbs would not reflect specifically American values.[134] Giving another line of reasoning that proverbs should not be trusted as a simplistic guide to cultural values, Mieder once observed “proverbs come and go, that is, antiquated proverbs with messages and images we no longer relate to are dropped from our proverb repertoire, while new proverbs are created to reflect the mores and values of our time”,[135] so old proverbs still in circulation might reflect past values of a culture more than its current values. Also, within any language’s proverb repertoire, there may be “counter proverbs”, proverbs that contradict each other on the surface[40] (see section above). When examining such counter proverbs, it is difficult to discern an underlying cultural value. With so many barriers to a simple calculation of values directly from proverbs, some feel "one cannot draw conclusions about values of speakers simply from the texts of proverbs".[136]

Seeking empirical evidence to evaluate the question of whether proverbs reflect a culture’s values, some have counted the proverbs that support various values. For example, Moon lists what he sees as the top ten core cultural values of the Builsa society of Ghana, as exemplified by proverbs. He found that 18% of the proverbs he analyzed supported the value of being a member of the community, rather than being independent.[137] This was corroboration to other evidence that collective community membership is an important value among the Builsa. In studying Tajik proverbs, Bell notes that the proverbs in his corpus “Consistently illustrate Tajik values” and “The most often observed proverbs reflect the focal and specific values” discerned in the thesis [138]

Some scholars have adopted a cautious approach, acknowledging at least a genuine, though limited, link between cultural vlaues and proverbs: “The cultural portrait painted by proverbs may be fragmented, contradictory, or otherwise at variance with reality... but must be regarded not as accurate renderings but rather as tantalizing shadows of the culture which spawned them.”[139] There is not yet agreement on the issue of whether, and how much, cultural values are reflected in a cultures proverbs.

It is clear that the Soviet Union believed that proverbs had a direct link to the values of a culture, as they used them to try to create changes in the values of cultures within their sphere of domination. Sometimes they took old Russian proverbs and altered them into socialist forms.[140] These new proverbs promoted Socialism and its attendant values, such as atheism and collectivism, e.g. “Bread is given to us not by Christ, but by machines and collective farms” and “A good harvest is had only by a collective farm.” They did not limit their efforts to Russian, but also produced “newly coined proverbs that conformed to socialist thought” in Tajik and other languages of the USSR.[141]

Proverbs and religion

Many proverbs from around the world address matters of ethics and expected of behavior. Therefore, it is not surprising that proverbs are often important texts in religions. The most obvious example is the Book of Proverbs in the Bible. Additional proverbs have also been coined to support religious values, such as the following from Dari of Afghanistan:[142] "In childhood you're playful, In youth you're lustful, In old age you're feeble, So when will you before God be worshipful?"

Clearly proverbs in religion are not limited to monotheists; among the Badaga of India (Sahivite Hindus), there is a traditional proverb "Catch hold of and join with the man who has placed sacred ash [on himself]."[143] Proverbs are widely associated with large religions that draw from sacred books, but they are also used for religious purposes among groups with their own traditional religions, such as the Guji Oromo.[24] The broadest comparative study of proverbs across religions is The eleven religions and their proverbial lore, a comparative study. A reference book to the eleven surviving major religions of the world by Selwyn Gurney Champion, from 1945. Some sayings from sacred books also become proverbs, even if they were not obviously proverbs in the original passage of the sacred book.[144] For example, many quote "Be sure your sin will find you out" as a proverb from the Bible, but there is no evidence it was proverbial in its original usage (Numbers 32:23).

Not all religious references in proverbs are positive, some are cynical, such as the Tajik "Do as the mullah says, not as he does."[145] Also, note the Italian proverb, "One barrel of wine can work more miracles than a church full of saints".

Dammann thought "The influence of Islam manifests itself in African proverbs... Christian influences, on the contrary, are rare."[146] If widely true in Africa, this is likely due to the longer presence of Islam in many parts of Africa. Reflection of Christian values is common in Amharic proverbs of Ethiopia, an area that has had a presence of Christianity for well over 1,000 years.

Proverbs and psychology

Though much proverb scholarship is done by literary scholars, those studying the human mind have used proverbs in a variety of studies. One of the earliest studies in this field is the Proverbs Test by Gorham, developed in 1956. A similar test is being prepared in German.[147] Proverbs have been used to evaluate dementia,[148][149] study the cognitive development of children,[9] measure the results of brain injuries,[150] and study how the mind processes figurative language.[151] [152]

Proverbs in advertising

Proverbs are frequently used in advertising, often in slightly modified form.[153] Ford once advertised its Thunderbird with, "One drive is worth a thousand words" (Mieder 2004b: 84). This is doubly interesting since the underlying proverb behind this, "One picture is worth a thousand words," was originally introduced into the English proverb repertoire in an ad for televisions (Mieder 2004b: 83).

A few of the many proverbs adapted and used in advertising include:

- "Live by the sauce, dine by the sauce" (Buffalo Wild Wings)

- "At D & D Dogs, you can teach an old dog new tricks" (D & D Dogs)

- "If at first you don't succeed, you're using the wrong equipment" (John Deere)

- "A pfennig saved is a pfennig earned." (Volkswagen)

- "Not only absence makes the heart grow fonder." (Godiva Chocolatier)

- "Where Hogs fly" (Grand Prairie AirHogs) baseball team

- "Waste not. Read a lot." (Half Price Books)

The GEICO company has created a series of television ads that are built around proverbs, such as "A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush":[154] and "The pen is mightier than the sword",[155] "Pigs may fly/When pigs fly",[156] and "If a tree falls in the forest..."[157]

Use of proverbs in advertising is not limited to the English language. Seda Başer Çoban has studied the use of proverbs in Turkish advertising.[158] Tatira has given a number of examples of proverbs used in advertising in Zimbabwe.[159] However, unlike the examples given above in English, all of which are anti-proverbs, Tatira's examples are standard proverbs. Where the English proverbs above are meant to make a potential customer smile, in one of the Zimbabwean examples "both the content of the proverb and the fact that it is phrased as a proverb secure the idea of a secure time-honored relationship between the company and the individuals". When newer buses were imported, owners of older buses compensated by painting a traditional proverb on the sides of their buses, "Going fast does not assure safe arrival".

Sources for proverb study

A seminal work in the study of proverbs is Archer Taylor's The Proverb (1931), later republished by Wolfgang Mieder with Taylor's Index included (1985/1934). A good introduction to the study of proverbs is Mieder's 2004 volume, Proverbs: A Handbook. Mieder has also published a series of bibliography volumes on proverb research, as well as a large number of articles and other books in the field. Stan Nussbaum has edited a large collection on proverbs of Africa, published on a CD, including reprints of out-of-print collections, original collections, and works on analysis, bibliography, and application of proverbs to Christian ministry (1998). Paczolay has compared proverbs across Europe and published a collection of similar proverbs in 55 languages (1997). Mieder edits an academic journal of proverb study, Proverbium (ISSN: 0743-782X), many back issues of which are available online.[160] A volume containing articles on a wide variety of topics touching on proverbs was edited by Mieder and Alan Dundes (1994/1981). Paremia is a Spanish-language journal on proverbs, with articles available online.[161] There are also papers on proverbs published in conference proceedings volumes from the annual Interdisciplinary Colloquium on Proverbs[162] in Tavira, Portugal.

See also

- Book of Proverbs

- List of proverbial phrases

- Old wives' tale

- Saw (saying)

- Wikiquote:English proverbs

- Wiktionary:Proverbs

Notes

- ↑ p. 12, Wolfgang Mieder. 1990. Not by bread alone: Proverbs of the Bible. New England Press.

- ↑ παροιμία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ↑ "T-shirt with anti-proverb". Neatoshop.com. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Proverbial Phrases from California", by Owen S. Adams, Western Folklore, Vol. 8, No. 2 (1949), pp. 95-116 doi:10.2307/1497581

- ↑ Williams, Fionnuala Carson. 2011. Alliteration in English-Language Versions of Current Widespread European Idioms and Proverbs. Jonathan Roper, (ed.) Alliteration in Culture, pp. 34-44. England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ↑ J. Raymond. 1956. Tensions in Proverbs: More Light on International Understanding. Western Folklore 15.3, pg 153-154

- ↑ John C. Messenger Jr. The Role of Proverbs in a Nigerian Judicial System. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 15:1 (Spring, 1959) pp. 64-73.

- ↑ E. Ojo Arewa and Alan Dundes. Proverbs and the Ethnography of Speaking Folklore. American Anthropologist. 66: 6, Part 2: The Ethnography of Communication (Dec 1964), pp. 70-85. Richard Bauman and Neil McCabe. Proverbs in an LSD Cult. The Journal of American Folklore. Vol. 83, No. 329 (Jul. - Sep., 1970), pp. 318-324.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Richard P. Honeck. A proverb in mind: the cognitive science of proverbial wit and wisdom. Routledge, 1997.

- ↑ p. 3 Archer Taylor. 1931. The Proverb. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ p. 25. Wolfgang Mieder. 1993. “The wit of one, and the wisdom of many: General thoughts on the nature of the proverb. Proverbs are never out of season: Popular wisdom in the modern age 3-40. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ p. 5. Wolfgang Mieder. 1993. “The wit of one, and the wisdom of many: General thoughts on the nature of the proverb. Proverbs are never out of season: Popular wisdom in the modern age 3-40. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ p. 73. Neil Norrick. 1985. How Proverbs Mean. Amsterdam: Mouton.

- ↑ p. 33. Sw. Anand Prahlad. 1996. African-American Proverbs in Context. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- ↑ p. 45. Alan Dundes. 1984. On whether weather 'proverbs' are proverbs. Proverbium 1:39-46. Also, 1989, in Folklore Matters edited by Alan Dundes, 92-97. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

- ↑ A Yorkshire proverb. 1883. The Academy. July 14, no. 584. p.30.

- ↑ Ezgi Ulusoy Aranyosi. 2010. "Atasözü neydi, ne oldu?" [“What was, and what now is, a 'proverb'?”]. Millî Folklor: International and Quarterly Journal of Cultural Studies 11.88: 5-15.

- ↑ p. 64. Gillian Hansford. 2003. Understanding Chumburung proverbs. Journal of West African Languages 30.1:57-82.

- ↑ p. 4,5. Daniel Ben-Amos. Introduction: Folklore in African Society. Forms of Folklore in Africa, edited by Bernth Lindfors, pp. 1-36. Austin: Univeristy of Texas.

- ↑ p. 43. Sabir Badalkhan. 2000. “Ropes break at the weakest point”: Some examples of Balochi proverbs with background stories. Proverbium 17:43-69.

- ↑ See Mac Coinnigh, Marcas. Syntactic Structures in Irish-Language Proverbs. Proverbium: Yearbook of International Proverb Scholarship 29, 95-136.

- ↑ Sebastian J. Floor. 2005. Poetic Fronting in a Wisdom Poetry Text: The Information Structure of Proverbs 7. Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 31: 23-58.

- ↑ Elias Dominguez Baraja. 2010. The function of proverbs in discourse. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Tadesse Jaleta Jirata. 2009. A contextual study of the social functions of Guji-Oromo proverbs. Saabruecken: DVM Verlag.

- ↑ Michael Stanton. 1996. Advice is a dangerous gift. Proverbium 13: 331-345

- ↑ Trokhimenko, Olga. 2003. “If You Sit on the Doorstep Long Enough, You Will Think of Something”: The Function of Proverbs in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Hobbit.” Proverbium (journal)20: 367-378.

- ↑ Unseth, Peter. 2011. A culture “full of choice apophthegms and useful maxims”: invented proverbs in C.S. Lewis’ The Horse and His Boy. Proverbium 28: 323-338.

- ↑ Richard Utz, "Sic et Non: Zu Funktion und Epistemologie des Sprichwortes bei Geoffrey Chaucer,” Das Mittelalter: Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung 2.2 (1997), 31-43.

- ↑ Sobieski, Janet and Wolfgang Mieder. 2005. "So many heads, so many wits": An anthology of English proverb poetry. (Supplement Series of Proverbium, 18.) Burlington, VT: University of Vermont.

- ↑ Heather A. Haas. 2011. The Wisdom of Wizards—and Muggles and Squibs: Proverb Use in the World of Harry Potter. Journal of American Folklore 124(492): 38.

- ↑ Jan Harold Brunvand. 2004. “The Early Bird Is Worth Two in the Bush”: Captain Jack Aubrey’s Fractured Proverbs. What Goes Around Comes Around: The Circulation of Proverbs in Contemporary Life, Kimberly J. Lau, Peter Tokofsky, Stephen D. Winick, (eds.), pp. 152-170. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. digitalcommons.usu.edu

- ↑ p. 49, Jennifer Speake. 2008. The Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs, 5th ed. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ George Bryan and Wolfgang Mieder. 1997. The Proverbial Charles Dickens. New York: Peter Lang

- ↑ George B. Bryan. 1993. Black Sheep, Red Herrings, and Blue Murder: The Proverbial Agatha Christie. Bern: Peter Lang.

- ↑ George B. Bryan and Wolfgang Mieder. 1994. The Proverbial Bernard Shaw: An Index to Proverbs in the Works of George Bernard Shaw. Heinemann Educational Books.

- ↑ Connable, Ben. (2009). All our eggs in a broken basket: How the Human Terrain System is undermining sustainable military cultural competence. Military Review, March–April: 57–64.

- ↑ Ismail I. Ahmed and Reginald H. Green. 1999. The heritage of war and state collapse in Somalia and Somaliland. Third World Quarterly 20.1:113-127.

- ↑ Sjaak van der Geest. 1996. The Elder and His Elbow: Twelve Interpretations of an Akan Proverb. Research in African Literatures Vol. 27, No. 3: 110-118.

- ↑ Michael Kiang, et al, Cognitive, neurophysiological, and functional correlates of proverb interpretation abnormalities in schizophrenia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (2007), 13, 653–663.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Charles Clay Doyle. 2012. Counter proverbs. In Doing proverbs and other kinds of folklore, by Charles Clay Doyle, 32-40. (Supplement series of Proverbium 33.) Burlington: University of Vermont.

- ↑ p. 52, Helen Atawube Yitah. 2006. Saying Their Own 'truth': Kasena Women's (de)construction of Gender Through Proverbial Jesting. Doctoral dissertation, University of Southern California.

- ↑ Bendt Alster. 1975. Paradoxical Proverbs and Satire in Sumerian Literature. Journal of Cuneiform Studies 27.4: 201-230.

- ↑ Russo, Joseph. 1983. The Poetics of the Ancient Greek Proverb. Journal of Folklore Research Vol. 20, No. 2/3, pp. 121-130

- ↑ Wandelt, Oswin. 1887. Sprichwörter und Sentenzen des altfranzösischen Dramas (1100-1400. Dissertation at Marburg Fr. Sömmering.

- ↑ Wilson, F.P. 1981. The proverbial wisdom of Shakespeare. In The Wisdom of Many: Essays on the Proverb, ed. by Wolfgang Mieder and Alan Dundes, p. 174-189. New York: Garland.

- ↑ Akíntúndé Akínyemi. 2007. The use of Yorùbá proverbs in Alin Isola's historical drama Madam Tinubu: Terror in Lagos. Proverbium 24:17-37.

- ↑ Stephen David Winick. 1998. "The proverb process: Intertextuality and proverbial innovation in popular culture". University of Pennsylvania dissertation.

- ↑ Stephen David Winick. 2013. Proverb is as proverb does. Proverbium30:377-428.

- ↑ Kevin McKenna. 2009. “Proverbs and the Folk Tale in the Russian Cinema: The Case of Sergei Eisenstein’s Film Classic Aleksandr Nevsky.” The Proverbial «Pied Piper» A Festschrift Volume of Essays in Honor of Wolfgang Mieder on the Occasion of His Sixty-Fifth Birthday, ed. by Kevin McKenna, pp. 277-292. New York, Bern: Peter Lang.

- ↑ Donald Haase. 1990. Is seeing believing? Proverbs and the adaptation of a fairy tale. Proverbium 7: 89-104.

- ↑ Elias Dominguez Baraja. 2010. The function of proverbs in discourse, p. 66, 67. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.

- ↑ Coteus, Stephen. 2011. "Trouble never sets like rain": Proverb (in)direction in Michael Thelwell's The Harder They Come. Proverbium 28:1-30.

- ↑ Pym, John. 1986/1987. Silly Girls. Sight and Sound 56.1:45-48.

- ↑ Konstantinova, Anna. 2012. Proverbs in an American musical: A cognitive-discursive study of "The Full Monty". Proverbium 29:67-93.

- ↑ p. 95 ff. Kwesi Yankah. 1989. The Proverb in the Context of Akan Rhetoric. Bern: Peter Lang.

- ↑ Ode S. Ogede. 1993. Proverb usage in the praise songs of Igede: Adiyah poet Micah Ichegbeh. Proverbium 10:237-256.

- ↑ Taft, Michael. 1994. Proverbs in the Blues. Proverbium 12: 227-258.

- ↑ Prahlad, Sw. Anand. 1996. African-American Proverbs in Context. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. See pp. 77ff.

- ↑ Steven Folsom. 1993. A discography of American Country music hits employing proverb: Covering the years 1986-1992. Proceedings for the 1993. Conference of the Southwest/Texas Popular Culture Association, ed. by Sue Poor, pp. 31-42. Stillwater, Oklahoma: The Association.

- ↑ Florian Gutman. 2007. "Because you're mine, I walk the line" Sprichwörliches in auswegewählten Liedern von Johnny Cash." Sprichwörter sind Goldes Wert, ed. by Wolfgang Mieder, pp. 177-194. (Supplement series of Proverbium 25). Burlington, VT: University of Vermont.

- ↑ V. Dezeljin. 1997. Funzioni testuali dei proverbi nel testo di Maldobrìe. Linguistica (Ljubljana) 37: 89-97.

- ↑ "Bruce Springsteen - My Best Was Never Good Enough - Live 2005 (opening night) video". YouTube. Retrieved 2012-09-20.

- ↑ Korosh Hadissi. 2010. A Socio-Historical Approach to Poetic Origins of Persian Proverbs. Iranian Studies 43.5: 599-605.

- ↑ Doyle, Charles Clay, Wolfgang Mieder, Fred R. Shapiro. 2012. The Dictionary of Modern Proverbs. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ↑ p. 325, Linda Tavernier-Almada. 1999. Prejudice, power, and poverty in Haiti: A study of a nation's culture as seen through its proverbs. Proverbium 16:325-350.

- ↑ Mesfin Wodajo. 2012. Functions and Formal and Stylistic Features of Kafa Proverbs. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing.

- ↑ p. 22, Janice Raymond. Mongolian Proverbs: A window into their world. San Diego: Alethinos Books.

- ↑ Charles Clay Doyle, Wolfgang Mieder, Fred R. Shapiro. 2012. The Dictionary of Modern Proverbs. Yale University Press.

- ↑ Photo and Web page about Permjakov

- ↑ p. 91 Grigorii L'vovich Permiakov. 1989. On the question of a Russian paremiological minimum. Proverbium 6:91-102.

- ↑ Grigorii L'vovich Permiakov. 1989. On the question of a Russian paremiological minimum. Proverbium 6:91-102.

- ↑ Katalin Vargha, Anna T. Litovkina. 2007. Proverb is as proverb does: A preliminary analysis of a survey on the use of Hungarian proverbs and anti-proverbs. Acta Ethnographica Hungarica 52.1: 135-155.

- ↑ "Paremiological Minimum of Czech: The Corpus Evidence - 1. INTRODUCTION. DATA FOR PROVERB RESEARCH". Ucnk.ff.cuni.cz. Retrieved 2012-09-20.

- ↑

- ↑ pp. 389-490, Valerie Inchley. 2010. Sitting in my house dreaming of Nepal. Kathmandu: EKTA.

- ↑ Doctor, Raymond. 2005. Towards a Paremiological Minimum For Gujarati Proverbs. Proverbium 22:51-70.

- ↑ Julia SEVILLA MUÑOZ. 2010. El refranero hoy. Paremia 19: 215-226.

- ↑ Fielder, Sabine. 1999. Phraseology in planned languages. Language Problems and Language Planning 23.2: 175-87, see p. 178.

- ↑ Victor Khachan. 2012. Courtroom proverbial murals in Lebanon: a semiotic reconstruction of justice. Social Semiotics DOI:10.1080/10350330.2012.665262

- ↑ Martin Charlot. 2007. Local Traffic Only: Proverbs Hawaiian Style. Watermark Publishing.

- ↑ Rose Marie Beck. 2000. Aesthetics of Communication: Texts on Textiles (Leso) from the East African Coast (Swahili). Research in African Literatures 31.4: 104-124)

- ↑ MacDowell, Marsha and Wolfgang Mieder. “‘When Life Hands You Scraps, Make a Quilt’: Quiltmakers and the Tradition of Proverbial Inscriptions.” Proverbium 27 (2010), 113-172.

- ↑ Corey Barksdale. 2011. Art & Inspirational Proverbs. Lulu.com.

- ↑ p. 426. Yoko Mori. 2012. Review of Dictionary of Japanese Illustrated Proverbs. Proverbium 29:435-456.

- ↑ pp. 203-213. Richard Honeck. 1997. A Proverb in Mind. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- ↑ database and e-research tool for art and design researchers (2012-10-20). "If the shoe doesn’t fit, must we change the foot?". Design and Art Australia Online. Daao.org.au. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ Trokhimenko, Olga V. 1999.”Wie ein Elefant im Porzellanlande”: Ursprung, Überlieferung und Gebrauch der Redensart in Deutschen un im Englischen. Proverbium 16: 351-380

- ↑ The Argyle Sweater, May 1, 2011.

- ↑ June 26, 2011.

- ↑ p. 126. Wolfgang Mieder. 1993. Proverbs are never out of season. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Aug 26, 2012.

- ↑ July 8, 2012

- ↑ Weintraut, Edward James. 1999. “Michel und Mauer”: Post-Unification Germany as seen through Editorial Cartoons. Die Unterrichtspraxis 32.2: 143-150.

- ↑ Dana Summers, Orlando Sentinel, Aug 20, 2012.

- ↑ p. 389. Wolfgang Mieder. 2013. Neues von Sisyphus: Sprichwörtliche Mythen der Anike in moderner Literatur, Medien und Karikaturen. Bonn: Praesens.

- ↑ Brienne Toomey. 2013. Old wisdom reimagined: Proverbial cartoons for university students. Proverbium 30: 333-346.

- ↑ Mieder, Wolfgang. 1982. Proverbs in Nazi Germany: The Promulgation of Anti-Semitism and Stereotypes Through Folklore. The Journal of American Folklore 95, No. 378, pp. 435–464.

- ↑ Wilson, April. 2004. Good Proverbs Make Good Students: Using Proverbs to Teach German Quickly. Proverbium: Yearbook of International Proverb Scholarship 21: 345-70.

- ↑ Cieslicka, Anna. 2002. Comprehension and Interpretation of Proverbs in L2. Studia Anglica Posnaniensia: An International Review of English Studies 37: 173-200.

- ↑

- ↑ Hendricks, Leo and Rosetta Hendricks. 1994. Efficacy of a day treatment program in management of diabetes for aging African Americans. In Vera Jackson, ed., Aging Families and the Use of Proverbs, 41-52. New York: The Haworth Press.

- ↑ Grady, Sandra. 2006. Hidden in decorative sight: Textile lore as proverbial communication among East African women. Proverbium 23: 169-190.

- ↑ Chindogo, M. 1997. Grassroot development facilitators and traditional local wisdom: the case of Malawi. Embracing the Baobab Tree: The African proverb in the 21st century, ed. by Willem Saayman, 125-135. (African Proverbs Series.) Pretoria: Unisa Press.

- ↑ Atido , George Pirwoth. 2011. Insights from Proverbs of the Alur in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In Collaboration with African Proverb Saying and Stories, www.afriprov.org. Nairobi, Kenya.

- ↑ "African Proverbs, Sayings and Stories". Afriprov.org. Retrieved 2012-09-20.

- ↑ Moon, Jay. 2009. African Proverbs Reveal Christianity in Culture (American Society of Missiology Monograph, 5). Pickwick Publications.

- ↑ Christaller, Johann. 1879. Twi mmebuse̲m, mpensã-ahansĩa mmoaano: A collection of three thousand and six hundred Tshi proverbs, in use among the Negroes of the Gold coast speaking the Asante and Fante language, collected, together with their variations, and alphabetically arranged. Basel: The Basel German Evangelical Missionary Society.

- ↑ Bailleul, Charles. 2005. Sagesse Bambara - Proverbes et sentences. Bamako, Mali: Editions Donniya.

- ↑ Johnson, William F. 1892. Hindi Arrows for the Preacher's Bow. (Dharma Dowali) Allahabad, India: Christian Literature Society.

- ↑ Houlder, J[ohn]. A[lden] (1885-1960). 1960. Ohabolana ou proverbes malgaches. Antananarivo: Imprimerie Luthérienne.

- ↑ Zellem, Edward. 2012. "Zarbul Masalha: 151 Afghan Dari Proverbs". Charleston: CreateSpace.

- ↑ Zellem, Edward. 2012. "Afghan Proverbs Illustrated". Charleston: CreateSpace., now also available with translations into German, French, and Russian.

- ↑ p. ii. Thomas Fielding. 1825. Select proverbs of all nations. New York: Covert.

- ↑ Gertrud Schneider-Blum. 2009. Máakuti t’awá shuultáa: Proverbs finish the problems: Sayings of the Alaaba (Ethiopia). Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- ↑ p. 90. Bartlotti, Leonard and Raj Wali Shah Khattak. 2006. Rohi Mataluna, revised and expanded ed. Peshawar, Pakistan: Interlit and Pashto Academy, Peshawar University.

- ↑ p. 18, Moran, William L. 1978. An Assyriological gloss on the new Archilochus fragment. Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 82: 17-19.

- ↑ p. 5, Alster, Bendt. 1979. An Akkadian and a Greek proverb. A comparative study. Die Welt des Orients 10:1-5.

- ↑ p. 67. Ju-Hong Yun and Pashai Language Committee. 2010. On a mountain there is still a road. Peshawar, Pakistan: InterLit Foundation.

- ↑ p. 24. Calvin C. Katabarwa and Angelique Chelo. 2012. Wisdom from Orma, Kenya proverbs and wise sayings. Nairobi: African Proverbs Working Group. http://www.afriprov.org/images/afriprov/books/wisdomofOrmaproverbs.pdf

- ↑ Kamil V. Zvelebil. 1987. The Sound of the One Hand. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 107, No. 1, pp. 125-126.

- ↑ p. 16, Edward Zellem. 2012. Zarbul Masalha: 151 Aghan Dari proverbs.

- ↑ p. 164. Philip B. Yampolsky, (trans.). 1977. The Zen Master Hakuin: Selected Writings. New York, Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Ludwik Sternbach. 1981. Indian Wisdom and Its Spread beyond India. Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 101, No. 1, pp. 97-131.

- ↑ Matti Kuusi; Marje Joalaid; Elsa Kokare; Arvo Krikmann; Kari Laukkanen; Pentti Leino; Vaina Mālk; Ingrid Sarv. Proverbia Septentrionalia. 900 Balto-Finnic Proverb Types with Russian, Baltic, German and Scandinavian Parallels. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia (1985)

- ↑ Fiedler, Sabine. 1999. Phraseology in planned languages. Language problems and language planning 23.2: ??.

- ↑ p. 92. Gertrud Schneider-Blum. 2009. Máakuti t’awá shuultáa: Proverbs finish the problems: Sayings of the Alaaba (Ethiopia). Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- ↑ Albert Kanlisi Awedoba. 2000. University Press Of America

- ↑ Linda Tavernier-Almada. 1999. Prejudice, power, and poverty in Haiti: a study of a nation’s culture as seen through its proverbs. Proverbium: Yearbook of International Proverb Scholarship 16:325-350.

- ↑ Ġorġ Mifsud-Chircop. 2001. Proverbiality and Worldview in Maltese and Arabic Proverbs. Proverbium: Yearbook of International Proverb Scholarship 18:247–55.

- ↑ Maati Kuusi. 1994. Fatalistic Traits in Finnish Proverbs. The Wisdom of Many. Essays on the Proverb, Eds. Wolfgang Mieder and Alan Dundes, 275-283. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. (Originally in Fatalistic Beliefs in Religion, Folklore and Literature, Ed. Helmer Ringgren. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1967. 89-96.

- ↑ Huynh Dinh Te. 1962. Vietnamese cultural patterns and values as expressed in proverbs. Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University.

- ↑ Gerald J. Wanjohi. 1997. The Wisdom and Philosophy of the Gikuyu Proverbs: The Kihooto Worldview. Nairobi, Paulines.

- ↑ Walter Grauberg. 1989. Proverbs and idioms: mirrors of national experience? Lexicographers and their works, ed. by Gregory James, 94-99. Exeter: University of Exeter.

- ↑ Richard Jente. 1931-1932. The American Proverb. American Speech 7:342-348.

- ↑ Wolfgang Mieder. 1993. Proverbs are never out of season: Popular wisdom in the modern age. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ p. 261. Sw. Anand Prahlad. 1996. African American Proverbs in Context. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- ↑ p. 134. W. Jay Moon. 2009. African Proverbs Reveal Christianity in Culture: A Narrative Portrayal of Builsa Proverbs. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications.

- ↑ p. 139 & 157. Evan Bell. 2009. An analysis of Tajik proverbs. Masters thesis, Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics.

- ↑ p. 173.Sheila K. Webster. 1982. Women, Sex, and Marriage in Moroccan Proverbs. International Journal of Middle East Studies 14:173-184.

- ↑ p. 84ff. Andrey Reznikov. 2009. Old wine in new bottles: Modern Russian anti-proverbs. (Supplement Series of Proverbium, 27.) Burlington, VT: University of Vermont

- ↑ Evan Bell. 2009. An analysis of Tajik proverbs. Masters thesis, Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics.

- ↑ p. 54, J. Christy Wilson, Jr. 2004. One hundred Afghan Persian proverbs 3rd, edition. Peshawar, Pakistan: InterLit Foundation.

- ↑ p. 601, Paul Hockings. 1988. Counsel from the Ancients: A study of Badaga proverbs, prayers, omens and curses. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- ↑ Ziyad Mohammad Gogazeh and Ahmad Husein Al-Afif. 2007. Los proverbios árabes extraidos del Corán: recopilación, traducción, y estudio. Paremia 16: 129-138.

- ↑ p. 130, Evan Bell. 2009. The wit and wisdom of the Tajiks: A analysis of Tajik proverbs. Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics, MA thesis.

- ↑ p. 46. Ernst Dammann. 1972. Die Religion in Afrikanischen Sprichwörter und Rätseln. Anthropos 67:36-48. Quotation in English, from summary at end of article.

- ↑ "Institut für Kognitive Neurowissenschaft". Ruhr-uni-bochum.de. 2011-03-22. Retrieved 2012-09-20.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, Haruyasu; Yohko Maki, Tomoharu Yamaguchi. 2011. A figurative proverb test for dementia: rapid detection of disinhibition, excuse and confabulation, causing discommunication. Psychogeriatrics Vol. 11.4: p. 205-211.

- ↑ Natalie C. Kaiser. 2013. What dementia reveals about proverb interpretation and its neuroanatomical correlates. Neuropsychologia 51:1726–1733.

- ↑ Pp. 123ff, C. Thomas Gualtieri. 2002. Brain Injury and Mental Retardation: Psychopharmacology and Neuropsychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ Ulatowska, Hanna K., and Gloria S. Olness. "Reflections on the Nature of Proverbs: Evidence from Aphasia." Proverbium 15 (1998), 329-346. Schizophrenia has also been shown to affect the way people interpret proverbs.

- ↑ Michael Kiang, et al, Cognitive, neurophysiological, and functional correlates of proverb interpretation abnormalities in schizophrenia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (2007), 13, 653–663.

- ↑ Wolfgang Mieder and Barbara Mieder. 1977. Tradition and innovation: Proverbs in advertising. Journal of Popular Culture 11: 308-319.

- ↑ "GEICO Commercial - Bird in Hand". YouTube. 2010-08-13. Retrieved 2011-11-09.

- ↑ "Is the Pen Mightier? - GEICO Commercial". YouTube. Retrieved 2011-11-09.

- ↑ "When pigs fly". Youtube.com. 2012-12-18. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ If a tree falls- GEICO commercial

- ↑ Seda Başer Çoban. 2010. Sözlü Gelenekten Sözün. Geleneksizliğine: Atasözü Ve Reklam [From Oral Tradition to the Traditionless of Speech: Proverb and Advertisement]. Millî Folklor. pp. 22-27.

- ↑ Liveson Tatira. 2001. Proverbs in Zimbabwean advertisements. Journal of Folklore Research 38.3: 229-241.

- ↑ http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/00693079

- ↑ "Paremia website". Paremia.org. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ "Conference website". Colloquium-proverbs.org. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

References

- Bailey, Clinton. 2004. A Culture of Desert Survival: Bedouin Proverbs from Sinai and the Negev. Yale University Press.

- Borajo, Daniel, Juan Rios, M. Alicia Perez, and Juan Pazos. 1990. Dominoes as a domain where to use proverbs as heuristics. Data & Knowledge Engineering 5:129-137.

- Dominguez Barajas, Elias. 2010. The function of proverbs in discourse. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Grzybek, Peter. "Proverb." Simple Forms: An Encyclopaedia of Simple Text-Types in Lore and Literature, ed. Walter Koch. Bochum: Brockmeyer, 1994. 227-41.

- Haas, Heather. 2008. Proverb familiarity in the United States: Cross-regional comparisons of the paremiological minimum. Journal of American Folklore 121.481: pp. 319–347.

- Hirsch, E. D., Joseph Kett, Jame Trefil. 1988. The dictionary of cultural literacy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Mac Coinnigh, Marcas. 2012. Syntactic Structures in Irish-Language Proverbs. Proverbium: Yearbook of International Proverb Scholarship 29, 95-136.

- Mieder, Wolfgang. 1982. Proverbs in Nazi Germany: The Promulgation of Anti-Semitism and Stereotypes Through Folklore. The Journal of American Folklore 95, No. 378, pp. 435–464.

- Mieder, Wolfgang. 1982; 1990; 1993. International Proverb Scholarship: An Annotated Bibliography, with supplements. New York: Garland Publishing.

- Mieder, Wolfgang. 1994. Wise Words. Essays on the Proverb. New York: Garland.

- Mieder, Wolfgang. 2001. International Proverb Scholarship: An Annotated Bibliography. Supplement III (1990–2000). Bern, New York: Peter Lang.

- Mieder, Wolfgang. 2004a. The Netherlandish Proverbs. (Supplement series of Proverbium, 16.) Burlington: University of Vermont.

- Mieder, Wolfgang. 2004b. Proverbs: A Handbook. (Greenwood Folklore Handbooks). Greenwood Press.

- Mieder, Wolfgang and Alan Dundes. 1994. The wisdom of many: essays on the proverb. (Originally published in 1981 by Garland.) Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Mieder, Wolfgang and Anna Tothne Litovkina. 2002. Twisted Wisdom: Modern Anti-Proverbs. DeProverbio.

- Mieder, Wolfgang and Janet Sobieski. 1999. Proverb iconography: an international bibliography. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Mitchell, David. 2001. Go Proverbs (reprint of 1980). ISBN 0-9706193-1-6. Slate and Shell.

- Nussbaum, Stan. 1998. The Wisdom of African Proverbs (CD-ROM). Colorado Springs: Global Mapping International.

- Obeng, S. G. 1996. The Proverb as a Mitigating and Politeness Strategy in Akan Discourse. Anthropological Linguistics 38(3), 521-549.

- Paczolay, Gyula. 1997. European Proverbs in 55 Languages. Veszpre’m, Hungary.

- Permiakov, Grigorii. 1979. From proverb to Folk-tale: Notes on the general theory of cliche. Moscow: Nauka.

- Pritchard, James. 1958. The Ancient Near East, vol. 2. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Raymond, Joseph. 1956. Tension in proverbs: more light on international understanding. Western Folklore 15.3:153-158.

- Taylor, Archer. 1985. The Proverb and an index to "The Proverb", with an Introduction and Bibliography by Wolfgang Mieder. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Zellem, Edward. 2012. "Zarbul Masalha: 151 Afghan Dari Proverbs". Charleston: CreateSpace.

- Zellem, Edward. 2012. "Afghan Proverbs Illustrated". Charleston: CreateSpace.

External links

| Look up Appendix:English proverbs in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Proverbs |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Category:Proverbs |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Proverbs. |

Serious websites related to the study of proverbs, and some that list regional proverbs:

- Associação Internacional de Paremiologia / International Association of Paremiology (AIP-IAP)

- Interdisciplinary Colloquium on Proverbs

- Proverb Bibliography by Francis Steen

- De Proverbio (electronic journal of international proverb studies)

- Proverbs, Maxims and Phrases of All Ages: 20,500 selections from the classic reference work

- Proverbs: Rough and Working Bibliography by Ted Hildebrandt. On Biblical Proverbs, Proverbial Folklore, and Psychology/Cognitive Literature

- African Proverbs, Sayings and Stories

- Folklore, particularly from the Baltic region, but many articles on proverbs

- Proverbs and Proverbial Materials in the Old Icelandic Sagas

- Select Proverbs (with Equivalents/Similars; English-American / Chinese / Turkish)

- Islamic Proverbs in World Languages

- Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs: Bibliography. A bibliography of first edition publications (and modern editions where they ease understanding) of proverb collections

- The Matti Kuusi international type system of proverbs