Probability theory

| Probability theory |

|---|

|

Probability theory is the branch of mathematics concerned with probability, the analysis of random phenomena.[1] The central objects of probability theory are random variables, stochastic processes, and events: mathematical abstractions of non-deterministic events or measured quantities that may either be single occurrences or evolve over time in an apparently random fashion. If an individual coin toss or the roll of dice is considered to be a random event, then if repeated many times the sequence of random events will exhibit certain patterns, which can be studied and predicted. Two representative mathematical results describing such patterns are the law of large numbers and the central limit theorem.

As a mathematical foundation for statistics, probability theory is essential to many human activities that involve quantitative analysis of large sets of data. Methods of probability theory also apply to descriptions of complex systems given only partial knowledge of their state, as in statistical mechanics. A great discovery of twentieth century physics was the probabilistic nature of physical phenomena at atomic scales, described in quantum mechanics.

History

The mathematical theory of probability has its roots in attempts to analyze games of chance by Gerolamo Cardano in the sixteenth century, and by Pierre de Fermat and Blaise Pascal in the seventeenth century (for example the "problem of points"). Christiaan Huygens published a book on the subject in 1657[2] and in the 19th century a big work was done by Laplace in what can be considered today as the classic interpretation.[3]

Initially, probability theory mainly considered discrete events, and its methods were mainly combinatorial. Eventually, analytical considerations compelled the incorporation of continuous variables into the theory.

This culminated in modern probability theory, on foundations laid by Andrey Nikolaevich Kolmogorov. Kolmogorov combined the notion of sample space, introduced by Richard von Mises, and measure theory and presented his axiom system for probability theory in 1933. Fairly quickly this became the mostly undisputed axiomatic basis for modern probability theory but alternatives exist, in particular the adoption of finite rather than countable additivity by Bruno de Finetti.[4]

Treatment

Most introductions to probability theory treat discrete probability distributions and continuous probability distributions separately. The more mathematically advanced measure theory based treatment of probability covers both the discrete, the continuous, any mix of these two and more.

Motivation

Consider an experiment that can produce a number of outcomes. The set of all outcomes is called the sample space of the experiment. The power set of the sample space is formed by considering all different collections of possible results. For example, rolling an honest die produces one of six possible results. One collection of possible results corresponds to getting an odd number. Thus, the subset {1,3,5} is an element of the power set of the sample space of die rolls. These collections are called events. In this case, {1,3,5} is the event that the die falls on some odd number. If the results that actually occur fall in a given event, that event is said to have occurred.

Probability is a way of assigning every "event" a value between zero and one, with the requirement that the event made up of all possible results (in our example, the event {1,2,3,4,5,6}) be assigned a value of one. To qualify as a probability distribution, the assignment of values must satisfy the requirement that if you look at a collection of mutually exclusive events (events that contain no common results, e.g., the events {1,6}, {3}, and {2,4} are all mutually exclusive), the probability that one of the events will occur is given by the sum of the probabilities of the individual events.[5]

The probability that any one of the events {1,6}, {3}, or {2,4} will occur is 5/6. This is the same as saying that the probability of event {1,2,3,4,6} is 5/6. This event encompasses the possibility of any number except five being rolled. The mutually exclusive event {5} has a probability of 1/6, and the event {1,2,3,4,5,6} has a probability of 1, that is, absolute certainty.

Discrete probability distributions

Discrete probability theory deals with events that occur in countable sample spaces.

Examples: Throwing dice, experiments with decks of cards, random walk,and tossing coins

Classical definition: Initially the probability of an event to occur was defined as number of cases favorable for the event, over the number of total outcomes possible in an equiprobable sample space: see Classical definition of probability.

For example, if the event is "occurrence of an even number when a die is rolled", the probability is given by  , since 3 faces out of the 6 have even numbers and each face has the same probability of appearing.

, since 3 faces out of the 6 have even numbers and each face has the same probability of appearing.

Modern definition:

The modern definition starts with a finite or countable set called the sample space, which relates to the set of all possible outcomes in classical sense, denoted by  . It is then assumed that for each element

. It is then assumed that for each element  , an intrinsic "probability" value

, an intrinsic "probability" value  is attached, which satisfies the following properties:

is attached, which satisfies the following properties:

That is, the probability function f(x) lies between zero and one for every value of x in the sample space Ω, and the sum of f(x) over all values x in the sample space Ω is equal to 1. An event is defined as any subset  of the sample space

of the sample space  . The probability of the event

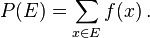

. The probability of the event  is defined as

is defined as

So, the probability of the entire sample space is 1, and the probability of the null event is 0.

The function  mapping a point in the sample space to the "probability" value is called a probability mass function abbreviated as pmf. The modern definition does not try to answer how probability mass functions are obtained; instead it builds a theory that assumes their existence.

mapping a point in the sample space to the "probability" value is called a probability mass function abbreviated as pmf. The modern definition does not try to answer how probability mass functions are obtained; instead it builds a theory that assumes their existence.

Continuous probability distributions

Continuous probability theory deals with events that occur in a continuous sample space.

Classical definition: The classical definition breaks down when confronted with the continuous case. See Bertrand's paradox.

Modern definition:

If the outcome space of a random variable X is the set of real numbers ( ) or a subset thereof, then a function called the cumulative distribution function (or cdf)

) or a subset thereof, then a function called the cumulative distribution function (or cdf)  exists, defined by

exists, defined by  . That is, F(x) returns the probability that X will be less than or equal to x.

. That is, F(x) returns the probability that X will be less than or equal to x.

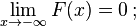

The cdf necessarily satisfies the following properties.

is a monotonically non-decreasing, right-continuous function;

is a monotonically non-decreasing, right-continuous function;

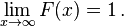

If  is absolutely continuous, i.e., its derivative exists and integrating the derivative gives us the cdf back again, then the random variable X is said to have a probability density function or pdf or simply density

is absolutely continuous, i.e., its derivative exists and integrating the derivative gives us the cdf back again, then the random variable X is said to have a probability density function or pdf or simply density

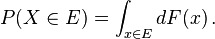

For a set  , the probability of the random variable X being in

, the probability of the random variable X being in  is

is

In case the probability density function exists, this can be written as

Whereas the pdf exists only for continuous random variables, the cdf exists for all random variables (including discrete random variables) that take values in

These concepts can be generalized for multidimensional cases on  and other continuous sample spaces.

and other continuous sample spaces.

Measure-theoretic probability theory

The raison d'être of the measure-theoretic treatment of probability is that it unifies the discrete and the continuous cases, and makes the difference a question of which measure is used. Furthermore, it covers distributions that are neither discrete nor continuous nor mixtures of the two.

An example of such distributions could be a mix of discrete and continuous distributions—for example, a random variable that is 0 with probability 1/2, and takes a random value from a normal distribution with probability 1/2. It can still be studied to some extent by considering it to have a pdf of ![(\delta [x]+\varphi (x))/2](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/7/1/d/c/71dc3577e7b34fe348d82d6e719b0360.png) , where

, where ![\delta [x]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/1/2/2/c/122c4f4409185db46dfe641cb74d219f.png) is the Dirac delta function.

is the Dirac delta function.

Other distributions may not even be a mix, for example, the Cantor distribution has no positive probability for any single point, neither does it have a density. The modern approach to probability theory solves these problems using measure theory to define the probability space:

Given any set  , (also called sample space) and a σ-algebra

, (also called sample space) and a σ-algebra  on it, a measure

on it, a measure  defined on

defined on  is called a probability measure if

is called a probability measure if

If  is the Borel σ-algebra on the set of real numbers, then there is a unique probability measure on

is the Borel σ-algebra on the set of real numbers, then there is a unique probability measure on  for any cdf, and vice versa. The measure corresponding to a cdf is said to be induced by the cdf. This measure coincides with the pmf for discrete variables and pdf for continuous variables, making the measure-theoretic approach free of fallacies.

for any cdf, and vice versa. The measure corresponding to a cdf is said to be induced by the cdf. This measure coincides with the pmf for discrete variables and pdf for continuous variables, making the measure-theoretic approach free of fallacies.

The probability of a set  in the σ-algebra

in the σ-algebra  is defined as

is defined as

where the integration is with respect to the measure  induced by

induced by

Along with providing better understanding and unification of discrete and continuous probabilities, measure-theoretic treatment also allows us to work on probabilities outside  , as in the theory of stochastic processes. For example to study Brownian motion, probability is defined on a space of functions.

, as in the theory of stochastic processes. For example to study Brownian motion, probability is defined on a space of functions.

Probability distributions

Certain random variables occur very often in probability theory because they well describe many natural or physical processes. Their distributions therefore have gained special importance in probability theory. Some fundamental discrete distributions are the discrete uniform, Bernoulli, binomial, negative binomial, Poisson and geometric distributions. Important continuous distributions include the continuous uniform, normal, exponential, gamma and beta distributions.

Convergence of random variables

In probability theory, there are several notions of convergence for random variables. They are listed below in the order of strength, i.e., any subsequent notion of convergence in the list implies convergence according to all of the preceding notions.

- Weak convergence: A sequence of random variables

converges weakly to the random variable

converges weakly to the random variable  if their respective cumulative distribution functions

if their respective cumulative distribution functions  converge to the cumulative distribution function

converge to the cumulative distribution function  of

of  , wherever

, wherever  is continuous. Weak convergence is also called convergence in distribution.

is continuous. Weak convergence is also called convergence in distribution.

- Most common shorthand notation:

- Most common shorthand notation:

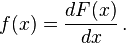

- Convergence in probability: The sequence of random variables

is said to converge towards the random variable

is said to converge towards the random variable  in probability if

in probability if  for every ε > 0.

for every ε > 0.

- Most common shorthand notation:

- Most common shorthand notation:

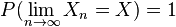

- Strong convergence: The sequence of random variables

is said to converge towards the random variable

is said to converge towards the random variable  strongly if

strongly if  . Strong convergence is also known as almost sure convergence.

. Strong convergence is also known as almost sure convergence.

- Most common shorthand notation:

- Most common shorthand notation:

As the names indicate, weak convergence is weaker than strong convergence. In fact, strong convergence implies convergence in probability, and convergence in probability implies weak convergence. The reverse statements are not always true.

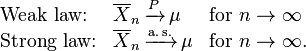

Law of large numbers

Common intuition suggests that if a fair coin is tossed many times, then roughly half of the time it will turn up heads, and the other half it will turn up tails. Furthermore, the more often the coin is tossed, the more likely it should be that the ratio of the number of heads to the number of tails will approach unity. Modern probability provides a formal version of this intuitive idea, known as the law of large numbers. This law is remarkable because it is not assumed in the foundations of probability theory, but instead emerges from these foundations as a theorem. Since it links theoretically derived probabilities to their actual frequency of occurrence in the real world, the law of large numbers is considered as a pillar in the history of statistical theory and has had widespread influence.[6]

The law of large numbers (LLN) states that the sample average

of a sequence of independent and

identically distributed random variables  converges towards their common expectation

converges towards their common expectation  , provided that the expectation of

, provided that the expectation of  is finite.

is finite.

It is in the different forms of convergence of random variables that separates the weak and the strong law of large numbers

It follows from the LLN that if an event of probability p is observed repeatedly during independent experiments, the ratio of the observed frequency of that event to the total number of repetitions converges towards p.

For example, if  are independent Bernoulli random variables taking values 1 with probability p and 0 with probability 1-p, then

are independent Bernoulli random variables taking values 1 with probability p and 0 with probability 1-p, then  for all i, so that

for all i, so that  converges to p almost surely.

converges to p almost surely.

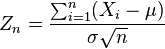

Central limit theorem

"The central limit theorem (CLT) is one of the great results of mathematics." (Chapter 18 in[7]) It explains the ubiquitous occurrence of the normal distribution in nature.

The theorem states that the average of many independent and identically distributed random variables with finite variance tends towards a normal distribution irrespective of the distribution followed by the original random variables. Formally, let  be independent random variables with mean

be independent random variables with mean  and variance

and variance  Then the sequence of random variables

Then the sequence of random variables

converges in distribution to a standard normal random variable.

See also

|

|

Notes

- ↑ "Probability theory, Encyclopaedia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ↑ Grinstead, Charles Miller; James Laurie Snell. "Introduction". Introduction to Probability. pp. vii.

- ↑ Hájek, Alan. "Interpretations of Probability". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ↑ ""The origins and legacy of Kolmogorov's Grundbegriffe", by Glenn Shafer and Vladimir Vovk" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ↑ Ross, Sheldon. A First course in Probability, 8th Edition. Page 26-27.

- ↑ "Leithner & Co Pty Ltd - Value Investing, Risk and Risk Management - Part I". Leithner.com.au. 2000-09-15. Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ↑ David Williams, "Probability with martingales", Cambridge 1991/2008

References

- Pierre Simon de Laplace (1812). Analytical Theory of Probability.

- The first major treatise blending calculus with probability theory, originally in French: Théorie Analytique des Probabilités.

- Andrei Nikolajevich Kolmogorov (1950). Foundations of the Theory of Probability.

- The modern measure-theoretic foundation of probability theory; the original German version (Grundbegriffe der Wahrscheinlichkeitrechnung) appeared in 1933.

- Patrick Billingsley (1979). Probability and Measure. New York, Toronto, London: John Wiley and Sons.

- Olav Kallenberg; Foundations of Modern Probability, 2nd ed. Springer Series in Statistics. (2002). 650 pp. ISBN 0-387-95313-2

- Henk Tijms (2004). Understanding Probability. Cambridge Univ. Press.

- A lively introduction to probability theory for the beginner.

- Olav Kallenberg; Probabilistic Symmetries and Invariance Principles. Springer -Verlag, New York (2005). 510 pp. ISBN 0-387-25115-4

- Gut, Allan (2005). Probability: A Graduate Course. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-22833-0.

External links

- Animation on the probability space of dice.

![f(x)\in [0,1]{\mbox{ for all }}x\in \Omega \,;](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/c/8/7/b/c87bbff867637f41b9463bebbf954c0f.png)