Pretelescopic astronomy

Pretelescopic astronomy is the science of observing celestial objects with the naked eye.

History

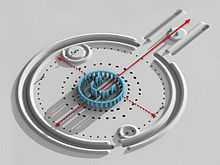

The worlds oldest observatory is known as the Goseck circle. Located in Germany, the enclosure is one of hundreds of similar wooden circular henges built throughout Austria, Germany, and the Czech Republic. While the sites vary in size—the one at Goseck is around 220 feet in diameter—they all have the same features. A narrow ditch surrounds a circular wooden wall, with a few large gates equally spaced around the outer edge. While scholars have known about the enclosures for nearly a century, they were stumped as to their exact function within the Stroke-Ornamented Pottery culture (known by its German acronym, STK) that dominated Central Europe at the time. The Goseck Henge is currently the oldest official 'Solar observatory' in the world. On the winter solstice, the sun could be seen to rise and set through the Southern gates from the centre. It has been observed that the entrances get progressively smaller the closer to the centre one gets, which would have concentrated the suns rays into a narrow path.

Being on the same latitude as Stonehenge means that 'astronomers' would have also benefitted from viewed the extremes of the sun and moon at right angles to each other. It is also sitting on one of two unique latitudes in the world at which the full moon passes directly overhead on its maximum Zeniths. [1] [2] [3]

The Nebra sky disk 1600 BC is one of the most important archaeological finds of the past century. It displays the world's oldest known concrete depiction of astronomical phenomena.[4]

Also discovered in Germany are the Magdalenenberg moon calendar. The royal tomb at Magdalenenberg, in Germany’s Black Forest, it is the largest Hallstatt tumulus grave in central Europe, measuring over 320 ft (100 m) across and (originally) 26 ft (8 m) high, its central grave was robbed in antiquity. More recent excavations have recovered the locations of numerous secondary burials placed around the edges of the mound and of various timber structures, including rows of wooden posts. There is nothing random about the secondary graves, which might be those of relatives or retainers, buried as they died during the years that followed their leader’s funeral. The order of the burials around the central royal tomb fits exactly the pattern of the constellations visible in the northern hemisphere at Midsummer in 618 BC, while the timber alignments mark the position not of the sunrise and sunset but of the moon, and notably the Lunar Standstill.

Following The Roman conquest of Gaul, the Gallic culture was destroyed and the Celtic calendar were completely forgotten in Europe, they were to be replaced by the Roman sun-based calendar.[5][6]

The Greek Anaximander's 610 – c. 546 BC bold use of non-mythological explanatory hypotheses considerably distinguishes him from previous cosmology writers such as Hesiod. It confirms that pre-Socratic philosophers were making an early effort to demythify physical processes. His major contribution to history was writing the oldest prose document about the Universe and the origins of life; for this he is often called the "Father of Cosmology" and founder of astronomy. However, pseudo-Plutarch states that he still viewed celestial bodies as deities.[7]

Anaximander was the first to conceive a mechanical model of the world. In his model, the Earth floats very still in the centre of the infinite, not supported by anything. It remains "in the same place because of its indifference", a point of view that Aristotle considered ingenious, but false, in On the Heavens.[8] Its curious shape is that of a cylinder[9] with a height one-third of its diameter. The flat top forms the inhabited world, which is surrounded by a circular oceanic mass.

Such a model allowed the concept that celestial bodies could pass under it. It goes further than Thales’ claim of a world floating on water, for which Thales faced the problem of explaining what would contain this ocean, while Anaximander solved it by introducing his concept of infinite (apeiron).

Some of the pretelesopic astronomers were the Chinese due to evidence such as the Gan Shi Xing Jing (the oldest recorded star catalog which was produced during the 5th century BCE).

Although the Chinese were among the first to document stellar activity, some of the oldest observatories on Earth are still extant throughout various regions of Korea, Egypt, Macedonia, Great Britain and Cambodia.

China has its observatories such as the Beijing Ancient Observatory, a facility constructed during the 13th century, equipped with instruments such as an armillary sphere, a quadrant, a theodolite and an astronomical sextant.

Oldest observatories

The five oldest, extant observatories according to NASA[citation needed] are as follows:

- Goseck circle, Germany from 4900 BC, it is the oldest known observatory in the world and predates the others by thousand of years.[10][11]

- Stonehenge, Great Britain started in 3000 BC

- Kokino, Republic of Macedonia 1900 BC [12]

- Abu Simbel, Egypt circa 1250 BC

- Angkor Wat, Cambodia 1100 AD

See also

- Nebra sky disk

- Naked-eye planets

- Chinese astronomy

- Archaeoastronomy

References

- ↑ http://www.sonnenobservatorium-goseck.info/home.html

- ↑ http://www.archaeology.org/0607/abstracts/henge.html

- ↑ http://www.ancient-wisdom.co.uk/germanygoseck.htm

- ↑ http://www.lda-lsa.de/en/nebra_sky_disc/

- ↑ http://www.world-archaeology.com/news/magdalenenberg-germanys-ancient-moon-calendar/

- ↑ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/10/111011074624.htm

- ↑ Pseudo-Plutarch, Doctrines of the philosophers, i. 7

- ↑ Aristotle, On the Heavens, ii, 13

- ↑ "A column of stone", Aetius reports in De Fide (III, 7, 1), or "similar to a pillar-shaped stone", pseudo-Plutarch (III, 10).

- ↑ http://www.archaeology.org/0607/abstracts/henge.html

- ↑ http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=circles-for-space

- ↑ http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5413/

- Hetherington, Barry (1992) A Chronicle of Pre-Telescopic Astronomy, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-95942-1

- Walker, Christopher, ed. (1996) Astronomy Before the Telescope, London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-1746-3