Pressure ulcer

| Pressure ulcer | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Classification of ulcers | |

| ICD-10 | L89 |

| ICD-9 | 707.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 10606 |

| MedlinePlus | 007071 |

| eMedicine | med/2709 |

| MeSH | D003668 |

Pressure ulcers, also known as decubitus ulcers or bedsores, are localized injuries to the skin and/or underlying tissue that usually occur over a bony prominence as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear and/or friction. The most common sites are the sacrum, coccyx, heels or the hips, but other sites such as the elbows, knees, ankles or the back of the cranium can be affected.

Pressure ulcers occur due to pressure applied to soft tissue resulting in completely or partially obstructed blood flow to the soft tissue. Shear is also a cause, as it can pull on blood vessels that feed the skin. Pressure ulcers most commonly develop in persons who are not moving about or are confined to wheelchairs. It is widely believed that other factors can influence the tolerance of skin for pressure and shear, thereby increasing the risk of pressure ulcer development. These factors are protein-calorie malnutrition, microclimate (skin wetness caused by sweating or incontinence), diseases that reduce blood flow to the skin, such as arteriosclerosis, or diseases that reduce the sensation in the skin, such as paralysis or neuropathy. The healing of pressure ulcers may be slowed by the age of the person, medical conditions (such as arteriosclerosis, diabetes or infection), smoking or medications such as antiinflammatory drugs.

Although often prevented and treatable if detected early, pressure ulcers can be very difficult to prevent in critically ill patients, frail elders, wheelchair users (especially where spinal injury is involved) and terminally ill patients. Primary prevention is to redistribute pressure by turning the patient regularly. The benefit of turning to avoid further sores is well documented since at least the 19th century. In addition to turning and re-positioning the patient in bed or wheelchair, eating a balanced diet with adequate protein and keeping the skin free from exposure to urine and stool is very important.

The prevalence of pressure ulcers in hospital settings is high, but improvements are being made. According to the 2010 International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence (IPUP) Survey conducted in Canada, there was a significant decrease in the overall facility-acquired prevalence of pressure ulcers from 2009-2010. Ulcers were most commonly identified at the sacral/coccyx ulcer location; however, heel ulcers were the most common facility-acquired location in the survey.[1]

Classification

The definitions of the four pressure ulcer stages are revised periodically by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisor Panel (NPUAP)[2] in the United States. Briefly, they are as follows:

- Stage I: Intact skin with non-blanchable redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence. Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching; its color may differ from the surrounding area. The area may be painful, firm, soft, warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. Stage I may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. May indicate “at risk” persons (a heralding sign of risk).

- Stage II: Partial thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum-filled blister. Presents as a shiny or dry shallow ulcer without slough or bruising. This stage should not be used to describe skin tears, tape burns, perineal dermatitis, maceration or excoriation.

- Stage III: Full thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible but bone, tendon or muscle are not exposed. Slough may be present but does not obscure the depth of tissue loss. May include undermining and tunneling. The depth of a stage III pressure ulcer varies by anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput and malleolus do not have (adipose) subcutaneous tissue and stage III ulcers can be shallow. In contrast, areas of significant adiposity can develop extremely deep stage III pressure ulcers. Bone/tendon is not visible or directly palpable.

- Stage IV: Full thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present on some parts of the wound bed. Often include undermining and tunneling. The depth of a stage IV pressure ulcer varies by anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput and malleolus do not have (adipose) subcutaneous tissue and these ulcers can be shallow. Stage IV ulcers can extend into muscle and/or supporting structures (e.g., fascia, tendon or joint capsule) making osteomyelitis likely to occur. Exposed bone/tendon is visible or directly palpable. In 2012, the NPUAP stated that pressure ulcers with exposed cartilage are also classified as a stage IV.

- Unstageable: Full thickness tissue loss in which actual depth of the ulcer is completely obscured by slough (yellow, tan, gray, green or brown) and/or eschar (tan, brown or black) in the wound bed. Until enough slough and/or eschar is removed to expose the base of the wound, the true depth, and therefore stage, cannot be determined. Stable (dry, adherent, intact without erythema or fluctuance) eschar on the heels is normally protective and should not be removed.

- Suspected Deep Tissue Injury: A purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-filled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, firm, mushy, boggy, warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. A deep tissue injury may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. Evolution may include a thin blister over a dark wound bed. The wound may further evolve and become covered by thin eschar. Evolution may be rapid exposing additional layers of tissue even with optimal treatment.

Healing time is prolonged for higher stage ulcers. While about 75% of Stage II ulcers heal within eight weeks, only 62% of Stage IV pressure ulcers ever heal, and only 52% heal within one year.[3] It is important to note that pressure ulcers do not regress in stage as they heal. A pressure ulcer that is becoming shallower with healing is described in terms of its original deepest depth (e.g., healing Stage II pressure ulcer).

Cause

Pressure ulcers are likely caused by three different tissue forces:

1. Pressure, or the compression of tissues and/or destruction of muscle cells. In most cases, this compression is caused by the force of bone against a surface, as when a patient remains in a single decubitus position for a lengthy period. After an extended amount of time with decreased tissue perfusion, ischemia occurs and can lead to tissue necrosis if left untreated. Pressure can also be exerted by external devices, such as medical devices, braces, wheelchairs, etc.

2. Shearing, a force created when the skin of a patient stays in one place as the deep fascia and skeletal muscle slide down with gravity, can also cause the pinching off of blood vessels which may lead to ischemia and tissue necrosis. Friction is related to shear but is considered less important in causing pressure ulcers.

3. Microclimate, the temperature and moisture of the skin in contact with the surface of the bed or wheelchair. Moisture on the skin causes the skin to lose the dry outer layer and reduces the tolerance of the skin for pressure and shear. The situation may be aggravated by other conditions such as excess moisture from incontinence, perspiration, or exudate. Over time, this excess moisture may cause the bonds between epithelial cells to weaken. thus resulting in the maceration of the epidermis. Temperature is also a very important factor. The cutaneous metabolic demand rises by 13% for every 1°C rise in cutaneous temperature. When supply can't meet demand, ischemia then occurs.

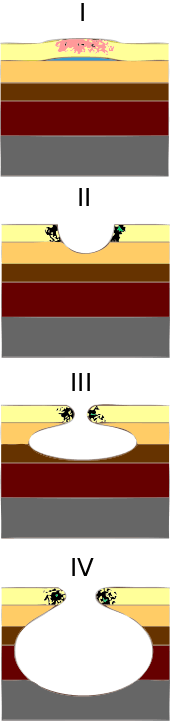

There are currently two major theories about the development of pressure ulcers. The first and most accepted is the deep tissue injury theory which claims that the ulcers begin at the deepest level, around the bone, and move outward until they reach the epidermis. The second, less popular theory is the top-to-bottom model which says that skin first begins to deteriorate at the surface and then proceeds inward.[4]

Risks

People who are immobile are at highest risk of developing pressure ulcers. The risk of developing bedsores can be predicted by using the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Ulcer Risk. The scale contains 6 areas of risk: cognitive-perceptual, immobility, inactivity, moisture, nutrition, friction/shear.

Pathophysiology

Pressure ulcers may be caused by inadequate blood supply and resulting reperfusion injury when blood re-enters tissue. A simple example of a mild pressure sore may be experienced by healthy individuals while sitting in the same position for extended periods of time: the dull ache experienced is indicative of impeded blood flow to affected areas. Within 2 hours, this shortage of blood supply, called ischemia, may lead to tissue damage and cell death. The sore will initially start as a red, painful area. The other process of pressure ulcer development is seen when pressure is high enough to damage the cell membrane of muscle cells. The muscle cells die as a result and skin fed through blood vessels coming through the muscle die. This is the deep tissue injury form of pressure ulcers and begins as purple intact skin.

Sites

Common sites affected by pressure sores are:[5] over ischial tuberosity, in relation to sacrum, in heel, over heads of metatarsals, buttocks, over shoulder, and over occiput.

Biofilm

Biofilm is one of the most common reasons for delayed healing in pressure ulcers. Biofilm occurs rapidly in wounds and stalls healing by keeping the wound inflamed. Frequent debridement and antimicrobial dressings are needed to control the biofilm. Infection prevents healing of pressure ulcers. Symptoms of infection in a pressure ulcer include slow or stalling healing and pale granulation tissue. See International Institute of Wound Infection. Infection can expand from local to systemic. Symptoms of systemic infection include fever, pain, redness, swelling, warmth of the area, and purulent discharge. Additionally, infected wounds may have a gangrenous smell, be discolored, and may eventually exude even more pus. In order to eliminate this problem, it is imperative to apply antiseptics at once. Hydrogen peroxide (a near-universal toxin) is not recommended for this task as it increases inflammation and impedes healing. [citation needed] Dressings with cadexomer iodine, silver or honey have been shown to penetrate biofilms. Systemic antibiotics are not recommended in treating local infection in a pressure ulcer, as it can lead to bacterial resistance. They are only recommended if there is evidence of advancing cellulitis, osteomyelitis, or bacteremia.[6]

Prevention

The most important care for patients at risk for pressure ulcers and those with bedsores is the redistribution of pressure so that no pressure is applied to the pressure ulcer. In the 1940s Ludwig Guttmann introduced a program of turning paraplegics every two hours thus allowing bedsores to heal. Previously such patients had a two year life-expectancy, normally succumbing to blood and skin infections. Guttmann had learned the technique from the work of Boston physician, Donald Munro.[7]

The NPUAP in conjunction with the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) published a comprehensive guideline on the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers in 2009.[8] Nursing homes and hospitals usually set programs in place to avoid the development of pressure ulcers in bedridden patients, such as using a routine time frame for turning and repositioning to reduce pressure. The frequency of turning and repositioning depends on the level of risk in the patient. Turning patients every 2 hours has been a long-standing tradition, with little evidence to support its practice. Pressure-redistributive mattresses are used to reduce high values of pressure on prominent or bony areas of the body. There are several important terms used to describe how these support surfaces work. These terms were standardized through the Support Surface Standards Initiative of the NPUAP. See S3I at npuap.org Many support surfaces redistribute pressure by immersing and/or enveloping the body into the surface. Some support surfaces, including antidecubitus mattresses and cushions, contain multiple air chambers that are alternately pumped.[9][10] Methods to standardize the products and evaluate the efficacy of these products have only been developed in recent years through the work of the S3I within NPUAP.[11] For individuals with paralysis, pressure shifting on a regular basis and using a wheelchair cushion featuring pressure relief components can help prevent pressure wounds.

Controlling the heat and moisture levels of the skin surface, known as skin microclimate management, also plays a significant role in the prevention and control of pressure ulcers.[12]

In addition, adequate intake of protein and calories is important. vitamin C has been shown to reduce the risk of pressure ulcers. People with higher intakes of vitamin C have a lower frequency of bed sores in bed-ridden patients than those with lower intakes. Vitamin C supplements have also been shown to help the healing of bed sores or pressure sores in a double-blind study. Maintaining proper nutrition in newborns is also important in preventing pressure ulcers. If unable to maintain proper nutrition through protein and calorie intake, it is advised to use supplements to support the proper nutrition levels.[13] Skin care is also important because damaged skin does not tolerate pressure. However, skin that is damaged by exposure to urine or stool is not considered a pressure ulcer. These skin wounds should be classified as Incontinence Associated Dermatitis.

In the UK the Royal College of Nursing has published guidelines in 'Pressure ulcer risk assessment and prevention'.[14] It is important to identify those who are at risk and to intervene early with strategies for prevention, in the bed, wheelchair or chair, in the bath and on the commode, and in fact it is a requirement within the National Standards for Care Homes (UK) to do so:

"Standard 8.3 Service users are assessed, by a person trained to do so, to identify those service users who have developed, or are at risk of developing, pressure sores and appropriate intervention is recorded in the plan of care. 8.4 The incidence of pressure sores, their treatment and outcome, are recorded in the service user’s individual plan of care and reviewed on a continuing basis. 8.5 Equipment necessary for the promotion of tissue viability and prevention or treatment of pressure sores is provided."[15]

Certain types of patients with risk of pressure ulcers require additional, specialized methods for prevention. One example is bariatric patients. Preventative measures for pressure ulcers in bariatric patients include:

- Holistic assessment: Nurses’ assessments should encompass and identify all high-risk breakdown areas for careful monitoring and include any comorbidities and their effects on the patient.

- Hygiene: Patient’s skin folds must be kept clean and dry to minimize the amount of moisture.

- Specialist equipment and safe manual handling: In order to avoid pressure damage, weight shifting is essential.[16]

Treatment

Debridement

Necrotic tissue should be removed in most pressure ulcers. The heel is an exception in many cases when the limb is poorly perfused. Necrotic tissue is an ideal area for bacterial growth, which has the ability to greatly compromise wound healing. There are five ways to remove necrotic tissue.

- Autolytic debridement is the use of moist dressings to promote autolysis with the body's own enzymes and white blood cells. It is a slow process, but mostly painless, and is most effective in patients with good immune systems.

- Biological debridement, or maggot debridement therapy, is the use of medical maggots to feed on necrotic tissue and therefore clean the wound of excess bacteria. Although this fell out of favour for many years, in January 2004, the FDA approved maggots as a live medical device.[17]

- Chemical debridement, or enzymatic debridement, is the use of prescribed enzymes that promote the removal of necrotic tissue.

- Mechanical debridement, is the use of debriding dressings, whirlpool or ultrasound for slough in a stable wound

- Surgical debridement, or sharp debridement, is the fastest method, as it allows a surgeon to quickly remove dead tissue.

Pressure ulcer intervention

Patients with pressure ulcers should not lie or sit on them. Continued pressure reduces the blood flow to a wound that is trying to heal. Specific wound care for pressure ulcers includes the following: Stage I pressure ulcers. Remove all pressure from the ulcer. No topical therapies have been shown to aid healing. Stage II pressure ulcers. Cover the wound bed with hydrocolloid or foam dressings. If the ulcer is on the buttocks, be certain the wound bed is clean before applying the dressings and replace the dressing if the wound bed becomes contaminated from urine or stool beneath the dressing. Skin care products that can be liberally applied to the ulcer are also an alternative to dressings and work well for the incontinent patient.

For those with Stage III or IV ulcers, once the necrotic tissue has been removed, fill the wound bed with a moisture retentive dressing or gel product to facilitate healing. Apply a cover dressing to hold the dressing or gel in place. Negative pressure wound therapy applied to the wound bed may also be used to improve granulation tissue formation in the pressure ulcer especially following surgical debridement. This technique uses foam or gauze placed into the wound cavity which is then covered in a film which creates an airtight seal. Once this seal is established, the negative pressure removes exudate and edema from the wound and stimulates blood supply to produce granulation tissue, capillary buds that begin the healing process in full-thickness ulcers. There are, unfortunately, contraindications to the use of negative pressure therapy. Most deal with the unprepared patient, one who has not gone through the previous steps toward recovery, but there are also wound characteristics that bar a patient from participating: a wound with inadequate circulation, a raw debrided wound, a wound with necrotised tissue and eschar, and a fibrotic wound or signs of cancer in the wound. After negative pressure wound therapy the patient should be reevaluated every two weeks to determine future therapy.

Clean full thickness pressure ulcers can be closed with surgery using tissue flap, free flap or other closure methods. Following these operations, no pressure or tension (pulling) can be applied to the flap while it is healing. Often the patient has to begin sitting up in short time increments to allow inspection of the flap for signs of pressure ulcer (unblanchable redness, pallor, incisional separation). Specialty low-air loss beds or air-fluidized beds are often required to promote healing of the flap in a low pressure environment.

Air Fluidized Therapy, often achieved with air fluidized therapy beds, can prevent further damage and salvage injured, yet viable tissue. Studies have been done to assess the benefit of Air Fluidized therapy on patients with suspected deep tissue injury. A recent study, Air Fluidized Therapy Use In Patients With Suspected Deep Tissue Injury - A Case Series has found positive results.

Complications

Pressure ulcers can trigger other ailments, cause patients considerable suffering, and be expensive to treat. Some complications include autonomic dysreflexia, bladder distension, osteomyelitis, pyarthroses, sepsis, amyloidosis, anemia, urethral fistula, gangrene and very rarely malignant transformation (Marjolin's ulcer - secondary carcinomas in chronic wounds). Sores often recur because patients do not follow recommended treatment or develop seromas, hematomas, infections, or dehiscence. Patients with paralysis are the most likely to have pressure sores recur. In some cases, complications from pressure sores can be life-threatening. The most common causes of fatality stem from renal failure and amyloidosis. Pressure ulcers are also painful, with patients of all ages and all stages of pressure ulcers reporting pain.

Epidemiology

Globally, as of 2010, pressure ulcers resulted in about 43,000 deaths.[18]

Each year, more than 2.5 million people in the United States develop pressure ulcers.[19] In acute care settings in the United States, the incidence of bedsores is 0.4% to 38%; within long-term care it is 2.2% to 23.9%, and in home care, it is 0% to 17%. Similarly, there is wide variation in prevalence: 10% to 18% in acute care, 2.3% to 28% in long-term care, and 0% to 29% in home care. There is a much higher rate of bedsores in intensive careunits because of immunocompromised individuals, with 8% to 40% of ICU patients developing bedsores.[20] However, pressure ulcer prevalence is highly dependent on the methodology used to collect the data. Using the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) methodology there are similar figures for pressure ulcers in acute hospital patients. There are differences across countries, but using this methodology pressure ulcer prevalence in Europe was consistently high, from 8.3% (Italy) to 22.9% (Sweden).[21] A recent study in Jordan also showed a figure in this range.[22]

References

- ↑ "2010 International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Survey: Canada Results".

- ↑ National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel

- ↑ Thomas DR, Diebold MR, Eggemeyer LM (2005). "A controlled, randomized, comparative study of a radiant heat bandage on the healing of stage 3-4 pressure ulcers: a pilot study". J Am Med Dir Assoc 6 (1): 46–9. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2004.12.007. PMID 15871870.

- ↑ Niezgoda JA, Mendez-Eastman S (2006). "The effective management of pressure ulcers". Adv Skin Wound Care. 19 Suppl 1: 3–15. doi:10.1097/00129334-200601001-00001. PMID 16565615.

- ↑ Bhat, Sriram (2013). Srb's Manual of Surgery, 4e. Jaypee Brother Medical Pub. p. 21. ISBN 9789350259443.

- ↑ American Family Physician. "Pressure Ulcers: Prevention, Evaluation, and Management". Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ D.Whitteridge, ‘Guttmann, Sir Ludwig (1899–1980)’, rev. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2012

- ↑ See npuap.org

- ↑ Guy H (2004). "Preventing pressure ulcers: choosing a mattress". Professional Nurse 20 (4): 43–46. PMID 15624622.

- ↑ "Antidecubitus Why?" (PDF). Antidecubitus Systems Matfresses Cushions. COMETE s.a.s. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ↑ Bain DS, Ferguson-Pell M (2002). "Remote monitoring of sitting behavior of people with spinal cord injury". J Rehabil Res Dev 39 (4): 513–20. PMID 17638148.

- ↑ https://library.hill-rom.com/browse?jobid=142

- ↑ NICHQ. "How To Guide Pediatric Supplement – Preventing Pressure Ulcers". Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/78501/001252.pdf

- ↑ Pressure Relief and Wound Care Independent Living (UK)

- ↑ "Bariatric Patient Care".

- ↑ "510(k)s Final Decisions Rendered for January 2004: DEVICE: MEDICAL MAGGOTS". FDA.

- ↑ Lozano, R (Dec 15, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.". Lancet 380 (9859): 2095–128. PMID 23245604.

- ↑ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. "Preventing Pressure Ulcers in Hospitals". Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ "Pressure ulcers in America: prevalence, incidence, and implications for the future. An executive summary of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel monograph". Adv Skin Wound Care 14 (4): 208–15. 2001. PMID 11902346.

- ↑ Vanderwee K, Clark M, Dealey C, Gunningberg L & Defloor T (2007). "Pressure ulcer prevalence in Europe: a pilot study". Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 13 (2): 227–235. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00684.x. PMID 17378869.

- ↑ Tubaishat A, Anthony DM, Saleh M (2010). "Pressure ulcers in Jordan: A point prevalence study". Journal of Tissue Viability 19 (4): 132–136. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2009.11.006. PMID 20036124.