Prenatal cocaine exposure

Prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE) occurs when a pregnant woman uses cocaine and thereby exposes her fetus to the drug. "Crack baby" was a term coined to describe children who were exposed to crack (cocaine in smokable form) as fetuses; the concept of the crack baby emerged in the US during the 1980s and 1990s in the midst of a crack epidemic.[2] Early studies reported that people who had been exposed to crack in utero would be severely emotionally, mentally, and physically disabled; this belief became common in the scientific and lay communities.[2] Fears were widespread that a generation of crack babies were going to put severe strain on society and social services as they grew up. Later studies failed to substantiate the findings of earlier ones that PCE has severe disabling consequences; these earlier studies had been methodologically flawed (e.g. with small sample sizes and confounding factors). Scientists have come to understand that the findings of the early studies were vastly overstated and that most people who were exposed to cocaine in utero do not have disabilities.[2]

No specific disorders or conditions have been found to result for people whose mothers used cocaine while pregnant.[3] Studies focusing on children of six years and younger have not shown any direct, long-term effects of PCE on language, growth, or development as measured by test scores.[4] PCE also appears to have little effect on infant growth.[5] However, PCE is associated with premature birth, birth defects, attention deficit disorder, and other conditions. The effects of cocaine on a fetus are thought to be similar to those of tobacco and less severe than those of alcohol.[6] No scientific evidence has shown a difference in harm to a fetus of crack and powder cocaine.[7]

PCE is very difficult to study because it very rarely occurs in isolation: usually it coexists with a variety of other factors, which may confound a study's results.[4] For example, pregnant mothers who use cocaine often use other drugs in addition, or they may be malnourished and lacking in medical care. Children in households where cocaine is abused are at risk of violence and neglect, and those in foster care may experience problems due to unstable family situations. Thus researchers have had difficulty in determining which effects result from PCE and which result from other factors in the children's histories.

Historical context

During the crack epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s in the US, fear existed throughout the country that PCE would create a generation of youth with severe behavioral and cognitive problems.[8] Early studies in the mid-1980s reported that cocaine use in pregnancy caused children to have severe problems including cognitive, developmental, and emotional disruption.[9] These early studies had methodological problems including small sample size, confounding factors like poor nutrition, and use of other drugs by the mothers.[9] However, the results of the studies sparked widespread media discussion in the context of the new War on Drugs.[10] For example a 1985 study that showed harmful effects of cocaine use during pregnancy created a huge media buzz.[9][11] The term "crack baby" resulted from the publicity surrounding crack and PCE.[12]

It was common in media reports of the phenomenon to emphasize that babies exposed to crack in utero would never develop normally.[12] The children were reported to be inevitably destined to be physically and mentally disabled for their whole lives.[2] Babies exposed to crack in utero were written off as doomed to be severely disabled, and many were abandoned in hospitals.[13] Experts foresaw the development of a "biological underclass" of born criminals who would prey on the rest of the population.[11][13] Crime rates were predicted to rise when the generation of crack-exposed infants grew up (instead they dropped).[13] It was predicted that the children would be difficult to console, irritable, and hyperactive, putting a strain on the school system.[5] Charles Krauthammer, a columnist for The Washington Post wrote in 1989, "[t]heirs will be a life of certain suffering, of probable deviance, of permanent inferiority."[11][13] The president of Boston University at the time, John Silber, said "crack babies ... won't ever achieve the intellectual development to have consciousness of God."[13] These claims of soullessness, "biological inferiority" and "born criminals" living in "inner cities" played easily into existing racial and class prejudice. Reporting was often sensational, favoring the direst predictions and shutting out skeptics.[14]

At the time, the proposed mechanism by which cocaine harmed fetuses was as a stimulant—it was predicted that cocaine would disrupt normal development of parts of the brain that dealt with stimulation, resulting in problems like bipolar disorder and attention deficit disorder.[2] Reports from the mid-1980s to early '90s raised concerns about links between PCE and slowed growth, deformed limbs, defects of the kidneys and genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts, neurological damage, small head size, atrophy or cysts in the cerebral cortex, bleeding into the brain's ventricles, obstruction of blood supply in the central nervous system.[15] Studies that find that exposure has significant effects may be more likely to be published than those that do not, a factor that may have biased reporting on the effects of PCE toward indicating more severe outcomes as the crack epidemic emerged.[15] Between 1980 and 1989, 57% of studies showing cocaine has effects on a fetus were accepted by the Society for Pediatric Research, compared with only 11% of studies showing no cocaine effects.[16]

After the early studies which reported that PCE children would be severely disabled came studies that purported to show that cocaine exposure in utero has no important effects.[13] Almost every prenatal complication originally thought to be due directly to PCE was found to result from confounding factors such as poor maternal nutrition, use of other drugs, depression, and lack of prenatal care.[17] More recently the scientific community has begun to reach an understanding that PCE does have some important effects but that they are not severe as was predicted in the early studies.[13] Most people who were exposed to cocaine in utero are normal.[2] The effects of PCE are subtle but they exist.[15][18][19]

Pathophysiology

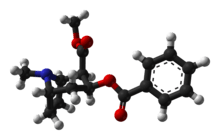

Cocaine, a small molecule, is able to cross the placenta into the bloodstream of the fetus.[1] In fact it may be present in a higher concentration in the amniotic fluid than it is in the mother's bloodstream.[20] The skin of the fetus is able to absorb the chemical directly from the amniotic fluid until the 24th week of pregnancy.[20] Cocaine can also show up in breast milk and affect the nursing baby.[20][21]

Cocaine prevents the reuptake of neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine and epinepherine, so they stay in the synapse longer, causing excitement of the sympathetic nervous system and evoking a stress response.[16] The euphoria experienced by cocaine users is thought to be largely due to the way it prevents the neurotransmitter serotonin from being reabsorbed by the presynaptic neuron which released it.[1]

Use of cocaine during pregnancy can negatively affect both the mother and the fetus.[16] But the ways in which cocaine affects a fetus are poorly understood.[17] There are multiple mechanisms by which cocaine exposure harms a fetus: it causes constriction (narrowing) of blood vessels and changes in brain chemistry, and it may alter expression of certain genes.[22] Cocaine affects neurotransmitters that are involved in the development of the fetus's brain.[23] Cocaine may affect fetal development directly by altering the development of the monoaminergic system in the brain.[24] In studies with rats, cocaine has been shown to cause apoptosis (programmed cell death) in fetuses; this could be a mechanism for some of the abnormalities of the heart associated with PCE.[1]

Another possible mechanism by which cocaine harms the fetus may be in part by interfering with blood supply to the uterus.[20][25] The reduction in blood flow to the uterus limits the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the fetus.[12] The reduced blood flow to the uterus may also play a role in congenital malformations and slowed fetal growth.[1] For example, it may be this reduction in blood flow that leads to gut damage in the infant.[20] Cocaine causes changes in the mother's blood pressure that are thought to be the cause of strokes in the fetus; one study found that 6% of cocaine-exposed infants had had one or more strokes.[20] Such prenatal strokes may be the cause of neurological problems found in some cocaine-exposed infants after birth.[5] Blood vessel contraction can also cause premature labor and birth.[12] Cocaine has also been found to enhance the contractility of the tissue in the uterus, another factor that has been suggested as a possible mechanism for its contribution to increased prematurity rates.[25] Increased contractility of the uterus may also be behind the increased likelihood of placental abruption (the placenta tearing away from the uterine wall) which some findings have linked with PCE.[16]

Diagnosis

Cocaine use during pregnancy can be discovered by asking the mother, but sometimes women will not admit to having used drugs; this "maternal interview" method has been found to be less reliable for discovering cocaine use than for other drugs such as marijuana.[26] More reliable methods for detecting cocaine exposure involve testing the newborn's hair or meconium (the infant's earliest stool).[26] Hair analysis, however, can give false positives for cocaine exposure.[26] The mother's urine can also be tested for drugs.[24]

Effects and prognosis

Drug use in the first trimester is the most harmful to the fetus in terms of neurological and developmental outcome.[27] The effects of PCE later in a child's life are poorly understood; there is little information about the effects of in utero cocaine exposure on children over age five.[4] Cocaine exposure in utero may affect the structure and function of the brain, predisposing children to developmental problems later, or these effects may be explained by children of crack-using mothers being at higher risk for domestic violence, insensitive parenting, and maternal depression.[4] Some studies have found PCE-related differences in height and weight while others have not; these differences are generally gone or small by the time children are school-age.[4] When researchers are able to identify effects that result from PCE, these effects are typically small.[17]

Some effects of PCE have been demonstrated with high exposures to cocaine but not with low ones.[24]

Studies have found that children exposed to cocaine during fetal development experience problems with language, behavior, development, and attention.[28] Some, but not all, PCE children experience hypertonia (excessive muscle tone), problems with attention, or delays in brain growth or language.[29] However, systematic reviews have found that after controlling for other factors that could be misleading, there is no evidence that fetal crack exposure causes problems different from those caused by other risk factors to which those fetuses are exposed.[30]

As many as 17–27% of cocaine-using pregnant women deliver prematurely.[25] There are also data showing that spontaneous abortion and low birth weight are associated with cocaine use.[11] The increased risk of placental abruption with cocaine use has been well documented.[1] Using cocaine while pregnant also heightens the chances of maternal and fetal vitamin deficiencies, respiratory distress syndrome for the baby, and infarction of the bowels.[20]

Early reports found that cocaine-exposed babies were at high risk for sudden infant death syndrome.[15] However, by itself, cocaine exposure during fetal development has not subsequently been identified as a risk factor for the syndrome.[30]

While newborns who were exposed prenatally to drugs such as barbiturates or heroin frequently have symptoms of drug withdrawal (neonatal abstinence syndrome), this does not happen with babies exposed to crack in utero; at least, such symptoms are difficult to separate in the context of other factors such as prematurity or prenatal exposure to other drugs.[12]

Unlike fetal alcohol syndrome, no set of characteristics has been discovered that results uniquely from cocaine exposure in utero.[17] Much is still not known about what factors may exist to aid children who were exposed to cocaine in utero.[17]

Mental, emotional, and behavioral outcomes

Little evidence suggests a link between fetal cocaine exposure and problems with cognitive development.[30] In IQ studies, cocaine-exposed children score no lower than others, and children exposed to marijuana and alcohol in utero were at the same level as those who were exposed to those drugs in addition to cocaine.[30] In school-age and younger children, PCE does not appear in studies to predispose children to poorer intellectual performance.[4] However, results of studies aiming to measure mental performance have been mixed, with some reporting measurable deficits in cocaine-exposed babies and others showing no differences between cocaine-exposed and control groups.[18] Studies of developmental delays have also been mixed.[24]

Cocaine causes impaired growth of the fetus's brain, an effect that is most pronounced with high levels of cocaine and prolonged duration of exposure throughout all three trimesters of pregnancy.[29] Those PCE children who had slowed brain growth as fetuses are at higher risk for impaired brain growth and motor, language and attention problems after they are born.[29]

Cognitive and attention skills can be impacted by PCE, possibly due to effects on brain areas such as the prefrontal cortex.[9] Children whose mothers used cocaine during pregnancy may develop symptoms akin to those of attention deficit disorder.[9] Language development has also been found in some studies to be impacted by PCE,[29] but language studies have failed to reliably show a detriment caused by in utero cocaine exposure.[30]

Evidence suggests that in utero cocaine exposure leads to problems with behavior and sustained attention, possibly by affecting parts of the brain that are vulnerable to toxins during fetal development.[4] The changes in behavior and attention caused by PCE are measurable by standardized scales;[29] however these behavioral effects seem to be mild.[9]

Physical outcomes

PCE may interfere with the way the motor system matures.[29] Reports on whether PCE affects motor functioning are mixed, with some reporting measurable deficits and others reporting none.[18] Some, but not all, studies have found impairments in development of motor skills in cocaine-exposed babies younger than seven months (but not older); however, this finding could be attributed to a failure to control for in utero tobacco exposure.[30]

A review of the literature reported that cocaine use causes congenital defects between 15 and 20% of the time; however another large-scale study found no difference in rates of birth anomalies in PCE and non-PCE infants.[31] Most PCE-related congenital defects are found in the brain, heart, genitourinary tract, arms and legs.[31] Abnormalities in the development of the heart both before and after birth have been linked to PCE; the mechanism by which this occurs is poorly understood.[1] Heart malformations can include a missing ventricle and defects with the septum of the heart, and can result in potentially deadly congestive heart failure.[1] Cocaine use by pregnant mothers may directly or indirectly contribute to defects in the formation of the circulatory system and is associated with abnormalities in development of the aorta.[25] Genital malformations occur at a higher-than-normal rate with PCE.[31] The liver and lungs are also at higher risk for abnormalities.[1] Cloverleaf skull, a congenital malformation in which the skull has three lobes, the brain is deformed, and hydrocephalus occurs, is also associated with PCE.[32] It is not well understood why cocaine exposure is associated with congenital malformations.[1] It has been suggested that some of these birth defects could be due to cocaine's disruption of blood vessel growth.[31]

Epidemiology

An estimated 0.6 to 3% of pregnant women worldwide use cocaine.[3] A 1995 survey in the US found that between 30,000 and 160,000 cases of prenatal exposure to cocaine occur each year.[33] By one estimate, in the US 100,000 babies are born each year after having been exposed to crack cocaine in utero.[25] Pregnant women in urban parts of the US and who are of a low socioeconomic status use cocaine more often.[24] However, the real prevalence of cocaine use by pregnant women is unknown.[17]

Legal and ethical issues

The harm to a child from PCE has implications for public policy and law. Some US states have pressed charges against pregnant women who use drugs, including child abuse, homicide, and distribution of drugs to a minor; however these approaches have generally been rejected in the courts on the basis that a fetus is not legally a child.[27] Between 1985 and 2001, more than 200 women in over 30 US states faced prosecution for drug use during pregnancy.[30] In South Carolina, a woman who used crack in her third trimester of pregnancy was sentenced to prison for eight years when her child was born with cocaine metabolites in its system.[27] The Supreme Court of South Carolina upheld this conviction.[27] From 1989 to 1994, in the midst of public outcry about cocaine babies, the Medical University of South Carolina tested pregnant women for cocaine, reporting those who tested positive to the police.[34] The US Supreme Court found the policy to be unacceptable on constitutional grounds in 2001.[34]

Some advocates argue that punishment for crack-using pregnant women as a means to treat their addiction is a violation of their right to privacy.[27] According to studies, fear of prosecution and having children taken away is associated with a refusal to seek prenatal care or medical treatment.[9]

Some nonprofit organizations aim to prevent PCE with birth control. One such initiative, Project Prevention, offers crack-addicted women money as an incentive to undergo long-term birth control or, frequently, sterilization—an approach which has led to public outcry from those who consider this practice to be eugenics.[35]

Social stigma

Children who were exposed to crack prenatally face social stigma as babies and school-aged children; some experts say that the "crack baby" social stigma is more harmful than the PCE.[11] Teachers who know that a child had been exposed to crack in utero may expect these children to be disruptive and developmentally delayed.[30] Children who were exposed to cocaine may be teased by others who know of the exposure, and problems these children have may be misdiagnosed by doctors or others as resulting from PCE when they may really be due to factors like illness or abuse.[8]

The social stigma of the drug also complicates studies of PCE; researchers labor under the awareness that their findings will have political implications.[8] In addition, the perceived hopelessness of 'crack babies' may cause researchers to ignore possibilities for early intervention that could help them.[5] The social stigma may turn out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy.[36]

Research

A number of the effects that had been thought after early studies to be attributable to prenatal exposure to cocaine are actually due partially or wholly to other factors, such as exposure to other substances (including tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana) or to the environment in which the child is raised.[30][31] Some effects (such as head circumference, body weight, and height) that appear in studies to result from prenatal cocaine exposure disappear when studies control for prenatal exposure to other drugs.[30]

PCE is very difficult to study because of a variety of factors that may confound the results: pre- and postnatal care may be poor; the pregnant mother and child may be malnourished; the amount of cocaine a mother takes can vary; she may take a variety of drugs during pregnancy in addition to cocaine; measurements for detecting deficits may not be sensitive enough; and results that are found may only last a short time.[33] PCE is clustered with other risk factors to the child such as maltreatment, domestic violence, and prenatal exposure to other substances.[31] Such environmental factors are known to adversely affect children in the same areas being studied with respect to PCE.[24] Most women who use cocaine while pregnant use other drugs too.[37] Addiction to any substance, including crack, may be a risk factor for child abuse or neglect.[30] Crack addiction, like other addictions, distracts parents from the child and leads to inattentive parenting.[12] Many drug users do not get prenatal care, for a variety of reasons including that they may not know they are pregnant.[27] Many crack addicts get no medical care at all and have extremely poor diets, and children who live around crack smoking are at risk of inhaling secondary smoke.[12] Cocaine using mothers also have a higher rate of to sexually transmitted infections such as HIV and hepatitis.[15] Drug use by mothers puts children at high risk for environmental problems, and PCE does not present much risk beyond these risk factors that occur alongside it.[4]

In some cases, it is not clear whether direct results of PCE lead to behavioral problems, or whether environmental factors are at fault.[4] For example, it may be that children who have caregiver instability have more behavioral problems as a result, or it may be that behavioral problems manifested by PCE children lead to greater turnover in caregivers.[4] Other factors that make studying PCE difficult include high rates of attrition (loss of participants) from studies, unwillingness of mothers to tell the truth about drug history, and uncertainty of dosages of street drugs.[24]

The difficulties in isolating crack exposure and other difficulties with studies mean that although many effects previously thought to have been attributable to crack exposure in utero have not been found, undiscovered effects may emerge as pressures on children grow as they reach school age and puberty.[30]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Feng, Q. (2005). "Postnatal consequences of prenatal cocaine exposure and myocardial apoptosis: Does cocaine in utero imperil the adult heart?". British Journal of Pharmacology 144 (7): 887. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706130. PMC 1576081. PMID 15685202.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Martin M. (May 3, 2010). "Crack Babies: Twenty Years Later". npr.org. National Public Radio. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lamy, S.; Thibaut, F. (2010). "Psychoactive substance use during pregnancy: a review". L'Encephale 36 (1): 33–38. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2008.12.009. PMID 20159194.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 Ackerman, J.; Riggins, T.; Black, M. (2010). "A review of the effects of prenatal cocaine exposure among school-aged children". Pediatrics 125 (3): 554–565. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0637. PMID 20142293.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Goldberg p.228

- ↑ Okie S (February 7, 2009). "Encouraging new on babies born to cocaine-abusing mothers". nytimes.com. The New York Times. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ↑ Lavoie D (December 25, 2007). "Crack-vs.-powder disparity is questioned". usatoday.com. USA Today. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Okie S. (January 26, 2009). "Crack Babies: The Epidemic That Wasn't". nytimes.com. The New York Times. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Thompson, B.; Levitt, P.; Stanwood, G. (2009). "Prenatal exposure to drugs: effects on brain development and implications for policy and education". Nature reviews. Neuroscience 10 (4): 303–312. doi:10.1038/nrn2598. PMC 2777887. PMID 19277053.

- ↑ Doweiko p.239

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Ornes S (December 2006). "What Ever Happened to Crack Babies? | Family Health | DISCOVER Magazine". discovermagazine.com. Discover Magazine. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Mercer, J (2009). "Claim 9: "Crack babies" can't be cured and will always have serious problems". Child Development: Myths and Misunderstandings. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications, Inc. pp. 62–64. ISBN 1-4129-5646-3.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Vargas T. (April 18, 2010). "Once written off, 'crack babies' have grown into success stories". washingtonpost.com. The Washington Post. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ↑ Greider, Katharine (August 1995). "crackpot ideas". Mother Jones.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Bauer, C. R.; Langer, J. C.; Shankaran, S.; Bada, H. S.; Lester, B.; Wright, L. L.; Krause-Steinrauf, H.; Smeriglio, V. L.; Finnegan, L. P.; Maza, P. L.; Verter, J. (2005). "Acute Neonatal Effects of Cocaine Exposure During Pregnancy". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 159 (9): 824–834. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.9.824. PMID 16143741.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Volpe p.1025

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Doweiko p.240

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Messinger, D. S.; Bauer, C. R.; Das, A.; Seifer, R.; Lester, B. M.; Lagasse, L. L.; Wright, L. L.; Shankaran, S.; Bada, H. S.; Smeriglio, V. L.; Langer, J. C.; Beeghly, M.; Poole, W. K. (2004). "The maternal lifestyle study: cognitive, motor, and behavioral outcomes of cocaine-exposed and opiate-exposed infants through three years of age". Pediatrics 113 (6): 1677–1685. doi:10.1542/peds.113.6.1677. PMID 15173491.

- ↑ Eiden, R.; McAuliffe, S.; Kachadourian, L.; Coles, C.; Colder, C.; Schuetze, P. (2009). "Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on infant reactivity and regulation". Neurotoxicology and Teratology 31 (1): 60. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2008.08.005. PMC 2631277. PMID 18822371.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 Doweiko p.241

- ↑ Yaffe p.417

- ↑ Lester, B.; Padbury, J. (2009). "Third pathophysiology of prenatal cocaine exposure". Developmental neuroscience 31 (1–2): 23–35. doi:10.1159/000207491. PMID 19372684.

- ↑ Singer, LT; Arendt, R; Minnes, S; Salvator, A; Siegel, AC; Lewis, BA (2001). "Developing language skills of cocaine-exposed infants". Pediatrics 107 (5): 1057–64. PMID 11331686.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 Singer, L.; Arendt, R.; Minnes, S.; Farkas, K.; Salvator, A.; Kirchner, H.; Kliegman, R. (2002). "Cognitive and motor outcomes of cocaine-exposed infants". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association 287 (15): 1952–1960. doi:10.1001/jama.287.15.1952. PMID 11960537.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Aronson p. 512–14

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Ostrea, E.; Knapp, D.; Tannenbaum, L.; Ostrea, A.; Romero, A.; Salari, V.; Ager, J. (2001). "Estimates of illicit drug use during pregnancy by maternal interview, hair analysis, and meconium analysis". The Journal of Pediatrics 138 (3): 344–348. doi:10.1067/mpd.2001.111429. PMID 11241040.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 Marrus, E. (2002). "Crack babies and the Constitution: ruminations about addicted pregnant women after Ferguson v. City of Charleston". Villanova law review 47 (2): 299–340. PMID 12680368.

- ↑ Lester, B.; Lagasse, L. (2010). "Children of addicted women". Journal of addictive diseases 29 (2): 259–276. doi:10.1080/10550881003684921. PMID 20407981.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 Ren, J.; Malanga, C.; Tabit, E.; Kosofsky, B. (2004). "Neuropathological consequences of prenatal cocaine exposure in the mouse". International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 22 (5–6): 309–320. doi:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.05.003. PMC 2664265. PMID 15380830.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 30.7 30.8 30.9 30.10 30.11 Frank, DA; Augustyn, M; Knight, WG; Pell, T; Zuckerman, B (2001). "Growth, development, and behavior in early childhood following prenatal cocaine exposure: a systematic review". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association 285 (12): 1613–25. doi:10.1001/jama.285.12.1613. PMC 2504866. PMID 11268270.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 Aronson p. 517

- ↑ Aronson p. 520

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Harvey JA (January 2004). "Cocaine effects on the developing brain: Current status". Neuroscience Biobehavioral Reviews 27 (8): 751–64. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.006. PMID 15019425.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Annas, G. J. (2001). "Testing Poor Pregnant Women for Cocaine — Physicians as Police Investigators". New England Journal of Medicine 344 (22): 1729–1732. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105313442219. PMID 11386286.

- ↑ "Sterilisation for drug addicts?". news.bbc.co.uk. May 18, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2010. Unknown parameter

|unused_data=ignored (help) - ↑ Connors GJ; Maisto SA; Galizio M (2007). Drug Use and Abuse. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing. p. 136. ISBN 0-495-09207-X.

- ↑ Richardson, G.; Day, N.; McGauhey, P. (1993). "The impact of prenatal marijuana and cocaine use on the infant and child". Clinical obstetrics and gynecology 36 (2): 302–318. doi:10.1097/00003081-199306000-00010. PMID 8513626.

Selected Bibliography

- Aronson JK (2008). "Cocaine". Meyler's Side Effects of Psychiatric Drugs. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. ISBN 0-444-53266-8.

- Doweiko, HE (2008). Concepts of Chemical Dependency. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 0-495-50580-3.

- Goldberg R (2009). "Cocaine amphetamines". Drugs Across the Spectrum. Pacific Grove: Brooks Cole. ISBN 0-495-55793-5.

- Volpe, JJ (2008). "Teratogenic effects of drugs and passive addiction". Neurology of the Newborn. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-3995-3.

- Yaffe, SJ; Briggs, GG; Freeman, RA (2008). "Cocaine". Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: A reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-7876-X.

- Lewis and Kestler (2011). Gender Differences in Prenatal Substance Exposure. Amer Psychological Society. ISBN 978-1-4338-1033-6.

- Soby, Jeanette M. (2006). Prenatal Exposure to Drugs/Alcohol: Characteristics And Educational Implications of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome And Cocaine/polydrug Effects. Charles C. Thomas Ltd. ISBN 978-0-398-07635-1.

- Steinberg, Wenzel, Kosofsky, Harvey, and Iguchi (2001). Prenatal Cocaine Exposure: Scientific Considerations and Policy Implications. 2001: RAND Drug Policy Research Center and NY Academy of Sciences. ISBN 978-0-8330-3001-6.

External links

- Crack Babies: A Tale from the Drug Wars, a documentary from The New York Times

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||