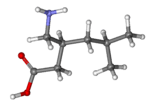

Pregabalin

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| (S)-3-(aminomethyl)-5-methylhexanoic acid | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Lyrica, Nervalin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605045 |

| Licence data | US Daily Med:link |

| Pregnancy cat. | B3 (Au), C (U.S.) |

| Legal status | Prescription Only (S4) (AU) POM (UK), Schedule V (U.S.) |

| Routes | oral |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ≥90% |

| Protein binding | Nil |

| Metabolism | Negligible |

| Half-life | 5–6.5 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 148553-50-8 |

| ATC code | N03AX16 |

| PubChem | CID 5486971 |

| DrugBank | DB00230 |

| ChemSpider | 4589156 |

| UNII | 55JG375S6M |

| KEGG | D02716 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:64356 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1059 |

| Synonyms | PD-144,723 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C8H17NO2 |

| Mol. mass | 159.23 g.mol-1 |

| SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

Pregabalin (INN) /prɨˈɡæbəlɨn/ is an anticonvulsant drug used for neuropathic pain and as an adjunct therapy for partial seizures with or without secondary generalization in adults.[1] It has also been found effective for generalized anxiety disorder and is (as of 2007) approved for this use in the European Union and Russia.[1] It was designed as a more potent successor to gabapentin. Pregabalin is marketed by Pfizer under the trade name Lyrica. Pfizer described in an SEC filing that the drug could be used to treat epilepsy, post-herpetic neuralgia, diabetic peripheral neuropathy and fibromyalgia. Sales reached a record $3.063 billion in 2010.[2] In Bangladesh Pregabalin is sold under the brand of Nervalin by Beximco Pharma It is effective at treating some causes of chronic pain such as fibromyalgia but not others. It is considered to have a low potential for abuse, and a limited dependence liability if misused, but is classified as a Schedule V drug in the U.S.[3]

Lyrica is one of four drugs which a subsidiary of Pfizer in 2009 pleaded guilty to misbranding "with the intent to defraud or mislead". Pfizer agreed to pay $2.3 billion (£1.4 billion) in settlement, and entered a corporate integrity agreement. Pfizer illegally promoted the drugs and caused false claims to be submitted to government healthcare programs for uses that were not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[4]

Medical uses

Pregabalin appears to be as effective as gabapentin for neuropathic pain; however costs more.[5] It is effective for some people with postherpetic neuralgia and fibromyalgia.[6] There is not enough data to state that it should be used in all neuropathic pain. It has not been found to be effective for HIV-associated peripheral neuropathy.[7] It has not been shown to be useful for cancer related neuropathic pain.[8] There is no evidence for use in acute pain.[6] Pregabalin is also used for the treatment perioperative pain.[9] There is no evidence for its use in the prevention of migraines and gabapentin has been found not to be useful.[10]

Pregabalin may be used as a second line medication in general anxiety disorder.[11] It appears to have anxiolytic effects similar to benzodiazepines.[12][13]

Adverse effects

Adverse drug reactions associated with the use of pregabalin include:[14][15]

- Very common (>10% of patients): dizziness, drowsiness.

- Common (1–10% of patients): blurred vision, diplopia, increased appetite and subsequent weight gain, euphoria, confusion, vivid dreams, changes in libido (increase or decrease), irritability, ataxia, attention changes, abnormal coordination, memory impairment, tremors, dysarthria, parasthesia, vertigo, dry mouth and constipation, vomiting and flatulence, erectile dysfunction, fatigue, peripheral oedema, drunkenness, abnormal walking, asthenia, nasopharyngitis, increased creatine kinase level.

- Infrequent (0.1–1% of patients): depression, lethargy, agitation, anorgasmia, hallucinations, myoclonus, hypoaesthesia, hyperaesthesia, tachycardia, excessive salivation, hypoglycaemia, sweating, flushing, rash, muscle cramp, myalgia, arthralgia, urinary incontinence, dysuria, thrombocytopenia, kidney calculus

- Rare (<0.1% of patients): neutropenia, first degree heart block, hypotension, hypertension, pancreatitis, dysphagia, oliguria, rhabdomyolysis, suicidal thoughts or behavior.[16]

Pregabalin may also cause withdrawal effects after long-term use if discontinued abruptly. When prescribed for seizures, quitting “cold turkey” can increase the strength of the seizures and possibly cause the seizures to reoccur. Withdrawal symptoms include difficulty sleeping, nausea, anxiety, diarrhoea, flu or flu-like symptoms, headache, increased sweating, convulsions, pain, dizziness, nervousness, and depression. Pregabalin should be reduced gradually when finishing treatment.

Overdosage

Several renal failure patients developed myoclonus while receiving pregabalin, apparently as a result of gradual accumulation of the drug. Acute overdosage may be manifested by somnolence, tachycardia and hypertonicity. Plasma, serum or blood concentrations of pregabalin may be measured to monitor therapy or to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients.[17][18][19]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Like gabapentin, pregabalin binds to the α2δ (alpha-2-delta) subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channel in the central nervous system. Pregabalin decreases the release of neurotransmitters including glutamate, norepinephrine, substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide.[20] However, unlike anxiolytic compounds (e.g., benzodiazepines) which exert their therapeutic effects through binding to GABAA, pregabalin neither binds directly to these receptors nor augments GABAA currents or affects GABA metabolism (Pfizer Inc., 2006).[21] The half-life for pregabalin is 6.3 hours.[22]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption: Pregabalin is rapidly absorbed when administered on an empty stomach, with peak plasma concentrations occurring within one hour. Pregabalin oral bioavailability is estimated to be greater than or equal to 90% and is independent of dose. The rate of pregabalin absorption is decreased when given with food resulting in a decrease in Cmax by approximately 25 to 30% and a delay in Tmax (time to reach Cmax) to approximately 2.5 hours. Administration with food, however, has no clinically significant effect on the extent of absorption.[23]

Distribution: Pregabalin has been shown to cross the blood–brain barrier in mice, rats, and monkeys. Pregabalin has been shown to cross the placenta in rats and is present in the milk of lactating rats. In humans, the volume of distribution of pregabalin for an orally administered dose is approximately 0.56 L/kg and is not bound to plasma proteins.[23]

Metabolism: Pregabalin undergoes negligible metabolism in humans.[24] In experiments using nuclear medicine techniques, it was revealed that approximately 98% of the radioactivity recovered in the urine was unchanged pregabalin. The major metabolite is N-methylpregabalin.[23]

Excretion: Pregabalin is eliminated from the systemic circulation primarily by renal excretion as unchanged drug.[23] Renal clearance of pregabalin is 73 mL/minute.[25]

History

Pregabalin was invented by medicinal chemist Richard Bruce Silverman at Northwestern University in the United States. The drug was approved in the European Union in 2004. Pregabalin received U.S. FDA approval for use in treating epilepsy, diabetic neuropathic pain, and postherpetic neuralgia in December 2004, and appeared on the U.S. market in fall 2005.[26]

In June 2007, the FDA approved Lyrica as a treatment for fibromyalgia. It was the first drug to be approved for this indication and remained the only one until duloxetine gained FDA approval for the treatment of fibromyalgia in June 2008.[27]

The patent for Lyrica currently expires in March 2018 (Silverman, R. B.; Andruszkiewicz, R. U. S. Pat. 6,197,819 B1 (March 6, 2001) “Gamma Amino Butyric Acid Analogs and Optical Isomers.”). This is the earliest possible date that a generic version of Lyrica could become available. However, there are other circumstances that could come up to extend the exclusivity period of Lyrica beyond 2018. These circumstances could include things such as lawsuits or other patents for specific Lyrica uses. Once Lyrica goes off patent, there may be several companies that manufacture a generic pregabalin drug.

Society and culture

Regulatory approval

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved pregabalin for adjunctive therapy for adults with partial onset seizures, management of postherpetic neuralgia and neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury and diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and the treatment of fibromyalgia.[9] Pregabalin has also been approved in the European Union and Russia (but not in US) for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder.[12][28]

Recreational use

Pregabalin is a Schedule V drug, and its classified as a CNS depressant. The potential for abuse of pregabalin is less than the potential with benzodiazepines; additionally the euphoric effects of pregabalin disappear with prolonged use.[29]

Marketing

Lyrica is one of four drugs which Pharmacia & Upjohn, a subsidiary of Pfizer, in 2009 pleaded guilty to misbranding "with the intent to defraud or mislead". Pfizer agreed to pay $2.3 billion (£1.4 billion) in settlement, and entered a corporate integrity agreement. Pfizer illegally promoted the drugs and caused false claims to be submitted to government healthcare programs for uses that were not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[30]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Benkert, Otto; Hippius, Hanns (2006). Kompendium Der Psychiatrischen Pharmakotherapie (in German) (6th ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-34401-8.

- ↑ "Portions of the Pfizer Inc. 2010 Financial Report". Sec.gov (edgar archives). Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ↑ Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Justice (July 2005). "Schedules of controlled substances: placement of pregabalin into schedule V. Final rule". Federal register 70 (144): 43633–5. PMID 16050051. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- ↑ "Pfizer agrees record fraud fine". BBC News. 2009-09-02. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ↑ Finnerup, NB; Sindrup SH; Jensen TS (September 2010). "The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain". Pain 150 (3): 573–81. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.019. PMID 20705215.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Moore, RA; Straube, S; Wiffen, PJ; Derry, S; McQuay, HJ (Jul 8, 2009). "Pregabalin for acute and chronic pain in adults.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (3): CD007076. PMID 19588419.

- ↑ Simpson, David M.; Schifitto, G.; Clifford, D.B. et al. (February 2010). "Pregabalin for painful HIV neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Neurology 74 (5): 413–420. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ccc6ef. PMC 2816006. PMID 20124207.

- ↑ Bennett, M.I. (November 2013). Pregabalin for acute and chronic pain in adults. PMID 23915361.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Pfizer to pay $2.3 billion to resolve criminal and civil health care liability relating to fraudulent marketing and the payment of kickbacks". Stop Medicare Fraud, US Dept of Health & Human Svc, and of Justice. Retrieved 2012-07-04.

- ↑ Linde, M; Mulleners, WM; Chronicle, EP; McCrory, DC (Jun 24, 2013). "Gabapentin or pregabalin for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine in adults.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 6: CD010609. PMID 23797675.

- ↑ Wensel TM, Powe KW, Cates ME (March 2012). "Pregabalin for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder". Ann Pharmacother 46 (3): 424–9. doi:10.1345/aph.1Q405. PMID 22395254.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Bandelow, Borwin; Wedekind, Dirk; Leon, Teresa (July 2007). "Pregabalin for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a novel pharmacologic intervention". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 7 (7): 769–781. doi:10.1586/14737175.7.7.769. PMID 17610384. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ↑ Owen, Richard T. (September 2007). "Pregabalin: its efficacy, safety and tolerability profile in generalized anxiety". Drugs of Today 43 (9): 601–10. doi:10.1358/dot.2007.43.9.1133188. PMID 17940637. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- ↑ Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd. Lyrica (Australian Approved Product Information). West Ryde: Pfizer; 2006.

- ↑ Rossi, Simone, ed. (2006). Australian Medicines Handbook, 2006. Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 978-0-9757919-2-9.

- ↑ "Medication Guide (Pfizer Inc.)" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. June 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ↑ Murphy, N.G.; Mosher, L. (2008). "Severe myoclonus from pregabalin (Lyrica) due to chronic renal insufficiency". Clinical Toxicology 46: 594.

- ↑ Yoo, Lawrence; Matalon, Daniel; Hoffman, Robert S.; Goldfarb, David S. (2009). "Treatment of pregabalin toxicity by hemodialysis in a patient with kidney failure". American Journal of Kidney Diseases 54 (6): 1127–30. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.014. PMID 19493601.

- ↑ Baselt, Randall C. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Biomedical Publications. pp. 1296–1297. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ↑ Micheva KD, Taylor CP, Smith SJ (April 2006). "Pregabalin Reduces the Release of Synaptic Vesicles from Cultured Hippocampal Neurons". Molecular Pharmacology 70 (2): 467–476. doi:10.1124/mol.106.023309. PMID 16641316.

- ↑ Strawn, JR; Geracioti Jr, TD (2007). "The treatment of generalized anxiety disorder with pregabalin, an atypical anxiolytic". Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment 3 (2): 237–43. doi:10.2147/nedt.2007.3.2.237. PMC 2654629. PMID 19300556.

- ↑ "Pregabalin". DRUGDEX. Micromedex. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 "Summary of product characteristics". European Medicines Agency. 6 March 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ↑ McElroy, Susan L.; Keck, Paul E.; Post, Robert M., eds. (2008). Antiepileptic Drugs to Treat Psychiatric Disorders. INFRMA-HC. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-8493-8259-8.

- ↑ "LYRICA - pregabalin capsule". DailyMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine. September 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ↑ Dworkin, Robert H.; Kirkpatrick, Peter (June 2005). "Pregabalin" (PDF). Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 4 (6): 455–456. doi:10.1038/nrd1756. PMID 15959952. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- ↑ "Living with Fibromyalgia, Drugs Approved to Manage Pain". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2008-07-18. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ↑ "Pfizer's Lyrica Approved for the Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) in Europe" (Press release). Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ↑ Chalabianloo, F; Schjøtt J (January 2009). "Pregabalin and its potential for abuse". Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association 129 (3): 186–187. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.08.0047. PMID 19180163.

- ↑ "Pfizer agrees record fraud fine". BBC News. 2009-09-02. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

External links

- Pfizer website for Lyrica

- U.S. prescribing information

- Lyrica (pregabalin) drug label/data at Daily Med from U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

- Lyrica Oral at WebMD.com

- Erowid Pregablin Vault, Pregabalin experience reports

| |||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||