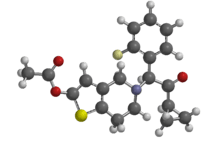

Prasugrel

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| (RS)-5-[2-cyclopropyl-1-(2-fluorophenyl)-2-oxoethyl]-4,5,6,7- tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridin-2-yl acetate | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Effient, Efient |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a609027 |

| Licence data | EMA:Link, US FDA:link |

| Pregnancy cat. | B (US) B |

| Legal status | POM (UK) ℞-only (US) |

| Routes | Oral |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ≥79% |

| Protein binding | Active metabolite: ~98% |

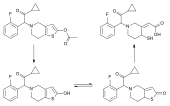

| Metabolism | Rapid intestinal and serum metabolism via esterase-mediated hydrolysis to a thiolactone (inactive), which is then converted, via CYP450-mediated (primarily CYP3A4 and CYP2B6) oxidation, to an active metabolite (R-138727) |

| Half-life | ~7 hours (range 2-15 hours) |

| Excretion | Urine (~68% inactive metabolites); feces (27% inactive metabolites) |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 150322-43-3 |

| ATC code | B01AC22 |

| PubChem | CID 6918456 |

| DrugBank | DB06209 |

| ChemSpider | 5293653 |

| UNII | 34K66TBT99 |

| KEGG | D05597 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201772 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C20H20FNO3S |

| Mol. mass | 373.442 g/mol |

| SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

Prasugrel (marketing name Effient in the US and India, and Efient in the EU) is a platelet inhibitor developed by Daiichi Sankyo Co. and produced by Ube and currently marketed in the United States in cooperation with Eli Lilly and Company for acute coronary syndromes planned for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Prasugrel was approved for use in Europe in February 2009, and is currently available in the UK. On July 10, 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of prasugrel for the reduction of thrombotic cardiovascular events (including stent thrombosis) in patients with acute coronary syndrome who are to be managed with PCI.[1]

Pharmacology

Prasugrel is a member of the thienopyridine class of ADP receptor inhibitors, like ticlopidine (trade name Ticlid) and clopidogrel (trade name Plavix). These agents reduce the aggregation ("clumping") of platelets by irreversibly binding to P2Y12 receptors. Compared to clopidogrel, prasugrel inhibits adenosine diphosphate–induced platelet aggregation more rapidly, more consistently, and to a greater extent than do standard and higher doses of clopidogrel in healthy volunteers and in patients with coronary artery disease, including those undergoing PCI.[2] Clopidogrel, unlike prasugrel, was issued a black box warning from the FDA on March 12, 2010, as the estimated 2-14% of the US population who have low levels of the CYP2C19 liver enzyme needed to activate clopidogrel may not get the full effect. Tests are available to predict if a patient would be susceptible to this problem or not.[3][4] Unlike clopidogrel, prasugrel is effective in most individuals, although several cases have been reported of decreased responsiveness to prasugrel.[5]

Pharmacodynamics

Prasugrel produces inhibition of platelet aggregation to 20 μM or 5 μM ADP, as measured by light transmission aggregometry.[6] Following a 60-mg loading dose of the drug, about 90% of patients had at least 50% inhibition of platelet aggregation by one hour. Maximum platelet inhibition was about 80%. Mean steady-state inhibition of platelet aggregation was about 70% following three to five days of dosing at 10 mg daily after a 60-mg loading dose. Platelet aggregation gradually returns to baseline values over five to 9 days after discontinuation of prasugrel, this time course being a reflection of new platelet production rather than pharmacokinetics of prasugrel. Discontinuing clopidogrel 75 mg and initiating prasugrel 10 mg with the next dose resulted in increased inhibition of platelet aggregation, but not greater than that typically produced by a 10-mg maintenance dose of prasugrel alone. Increasing platelet inhibition could increase bleeding risk. The relationship between inhibition of platelet aggregation and clinical activity has not been established.[7]

Pharmacokinetics

Prasugrel is a prodrug and is rapidly metabolized to a pharmacologically active metabolite and inactive metabolites. The active metabolite has an elimination half-life of about 7 hr (range 2–15 hr). Healthy subjects, patients with stable atherosclerosis, and patients undergoing PCI show similar pharmacokinetics.

TRITON-TIMI 38 study

As published in the New England Journal of Medicine's online edition, the TRITON-TIMI 38 study of 13,608 patients with acute coronary syndromes (moderate- to high-risk) and with scheduled percutaneous coronary intervention compared prasugrel against clopidogrel, both in combination with aspirin, and found that, as a more potent antiplatelet agent, prasugrel reduced the combined rate of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke (12.1% for clopidogrel vs. 9.9% for prasugrel). This difference in the primary endpoint was mainly driven by the reduction of nonfatal myocardial infarctions. However, an increased rate of serious bleedings (1.4%, vs. 0.9% in the clopidogrel group) and fatal bleedings (0.4% vs. 0.1%) was also observed.[2] Overall mortality did not differ between the two treatment groups.

From the editorial in the NEJM, "In TRITON–TIMI 38, for each death from cardiovascular causes prevented by the use of prasugrel as compared with clopidogrel, approximately one additional episode of fatal bleeding was caused by prasugrel".[8]

In patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), prasugrel was associated with a significantly lower incidence of ischemic events than clopidogrel, and was particularly effective in specific subgroups of patients, such as those with diabetes mellitus. This subgroup has a 30% relative risk reduction (4.2% ARR for unstable angina/NSTEMI and 5% AAR for STEMI) compared to the clopidogrel group without significant increased risk for major bleeding (2.2% vs. 2.3%).

However, the efficacy of prasugrel was offset by a higher risk of bleeding than clopidogrel, with patients aged ≥75 years, those weighing <60 kg, and those with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack at the greatest risk. A lower dose of prasugrel in patients aged ≥75 years and those weighing <60 kg may help to minimize the bleeding risk, although more data are needed to establish this; prasugrel is contraindicated in patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack.[9] The estimated number of patients needed to be treated with prasugrel at the dosage studied, as compared with standard-dose clopidogrel, to prevent one primary efficacy end point during a 15-month period was 46. The number of patients who would have to be treated to result in an excess non–CABG-related TIMI major hemorrhage was 167.[2]

Furthermore, data from a pharmacodynamic study suggest that ACS patients can be safely switched from clopidogrel to prasugrel and that doing so results in a further reduction in platelet function after one week. When patients receive a loading dose of prasugrel prior to switching from clopidogrel, the reduction in platelet function occurs within two hours.[10]

TRILOGY ACS study

In the TRILOGY ACS study on high-risk patients with ACS who are medically managed without revascularization, prasugrel has failed to show a reduction in major cardiovascular events compared with clopidogrel. No differences were found between rates of GUSTO severe/life-threatening and TIMI major bleeding, fatal, and intracranial bleeding between the prasugrel and clopidogrel groups in participants <75 years and the overall population. A lower dose of prasugrel (5 mg) was used in those aged 75 and over and in those weighing less than 60 kg and appeared to be safe.[11]

Interactions

As opposed to clopidogrel, proton pump inhibitors do not reduce the antiplatelet effects of prasugrel and hence it is relatively safe to use these medications together.[12]

Contraindications

Do not use prasugrel in patients with active pathological bleeding, such as peptic ulcer or a history of transient ischemic attack or stroke, because of higher risk of stroke (thrombotic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage).[13]

Adverse effects

- Cardiovascular: Hypertension (8%), hypotension (4%), atrial fibrillation (3%), bradycardia (3%), noncardiac chest pain (3%), peripheral edema (3%), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

- Central nervous system: Headache (6%), dizziness (4%), fatigue (4%), fever (3%), extremity pain (3%)

- Dermatologic: Rash (3%)

- Endocrine and metabolic: Hypercholesterolemia/hyperlipidemia (7%)

- Gastrointestinal: Nausea (5%), diarrhea (2%), gastrointestinal hemorrhage (2%)

- Hematologic: Leukopenia (3%), anemia (2%)

- Neuromuscular and skeletal: Back pain (5%)

- Respiratory: Epistaxis (6%), dyspnea (5%), cough (4%)

- Hypersensitivity, including angioedema

Patents

- US 5288726 claims prasugrel compound; will be expire on 14 Apr 2017

- US 6693115 claims hydrochloride salt of prasugrel; will expire on 3 Jul 2021

References

- ↑ Baker WL, White CM. Role of Prasugrel, a Novel P2Y12 Receptor Antagonist, in the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes. American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs Aug 1, 2009; 9 (4): 213-229. Link text

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH et al. (2007). "Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes". N Engl J Med 357 (20): 2001–15. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706482.

- ↑ "FDA Announces New Boxed Warning on Plavix: Alerts patients, health care professionals to potential for reduced effectiveness" (Press release). Food and Drug Administration (United States). March 12, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Reduced effectiveness of Plavix (clopidogrel) in patients who are poor metabolizers of the drug". Drug Safety and Availability. Food and Drug Administration (United States). March 12, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ↑ Silvano M, et al. (2011). "A case of resistance to clopidogrel and prasugrel after percutaneous coronary angioplasty.". J Thromb Thrombolysis. 31(2) (2): 233–4. doi:10.1007/s11239-010-0533-x. PMID 21088983.

- ↑ O'Riordan, Michael. "Switching from clopidogrel to prasugrel further reduces platelet function". http://www.theheart.org. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ↑ Efient: Highlights of prescribing information

- ↑ Bhatt DL (2007). "Intensifying Platelet Inhibition — Navigating between Scylla and Charybdis". N Engl J Med 357 (20): 2078–81. doi:10.1056/NEJMe0706859. PMID 17982183.

- ↑ Duggan ST, Keating GM. Prasugrel: A Review of its Use in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Drugs Aug 20, 2009; 69 (12): 1707-26 Link text

- ↑ O'Riordan, Michael. "Switching from clopidogrel to prasugrel further reduces platelet function". 1.Angiolillo DJ, Saucedo JF, DeRaad R, et al. Increased platelet inhibition after switching from maintenance clopidogrel to prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56: 1017-23. http://www.theheart.org. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ↑ Roe MT, Armstrong PW, Fox KAA, et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel for ACS patients managed without revascularization" N Engl J Med 2012; DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1205512. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1205512#t=articleResults

- ↑ John, Jinu; Koshy S (2012). "Current Oral Antiplatelets: Focus Update on Prasugrel". Journal of american board of family medicine 25: 343–349. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2012.03.100270.

- ↑ Effient (prasugrel hydrochloride) Prescribing Information September 2011 http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm275490.htm

External links

- Prasugrel information at Prous Science

- http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/online/webcasts/acute-coronary-syndrome/non-st-elevation/webcast.asp ; Use of prasugrel vs clopidogrel and other anti-aggregant drugs in ACS

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||