Power inverter

A power inverter, or inverter, is an electronic device or circuitry that changes direct current (DC) to alternating current (AC).[1]

The input voltage, output voltage and frequency, and overall power handling, are dependent on the design of the specific device or circuitry.

A power inverter can be entirely electronic or may be a combination of mechanical effects (such as a rotary apparatus) and electronic circuitry. Static inverters do not use moving parts in the conversion process.

Typical applications for power inverters include:

- Portable consumer devices that allow the user to connect a battery, or set of batteries, to the device to produce AC power to run various electrical items such as lights, televisions, kitchen appliances, and power tools.

- Use in power generation systems such as electric utility companies or solar generating systems to convert DC power to AC power.

- Use within any larger electronic system where an engineering need exists for deriving an AC source from a DC source.

Input and output

Input voltage

A typical power inverter device or circuit will require a relatively stable DC power source capable of supplying enough current for the intended overall power handling of the inverter. Possible DC power sources include: rechargeable batteries, DC power supplies operating off of the power company line, and solar cells. The inverter does not produce any power, the power is provided by the DC source. The inverter translates the form of the power from direct current to an alternating current waveform.

The level of the needed input voltage depends entirely on the design and purpose of the inverter. In many smaller consumer and commercial inverters a 12V DC input is popular because of the wide availability of powerful rechargeable 12V lead acid batteries which can be used as the DC power source.

Output waveform

An inverter can produce square wave, modified sine wave, pulsed sine wave, or sine wave depending on circuit design. The two dominant commercialized waveform types of inverters as of 2007 are modified sine wave and sine wave.

There are two basic designs for producing household plug-in voltage from a lower-voltage DC source, the first of which uses a switching boost converter to produce a higher-voltage DC and then converts to AC. The second method converts DC to AC at battery level and uses a line-frequency transformer to create the output voltage.[2]

Square wave

This is one of the simplest waveforms an inverter design can produce and is useful for some applications.

Sine wave

A power inverter device which produces a smooth sinusoidal AC waveform is referred to as a sine wave inverter. To more clearly distinguish from "modified sine wave" or other creative terminology, the phrase pure sine wave inverter is sometimes used.

In situations involving power inverter devices which substitute for standard line power, a sine wave output is extremely desirable because the vast majority of electric plug in products and appliances are engineered to work well with the standard electric utility power which is a true sine wave.

At present, sine wave inverters tend to be more complex and have significantly higher cost than a modified sine wave type of the same power handling.[3]

Modified sine wave

The terminology "modified sine wave" has come into use and refers to an output waveform that is a useful rough approximation of a sine wave for power translation purposes.

The waveform in commercially available modified-sine-wave inverters is a square wave with a pause before the polarity transition, which only needs to cycle through a three-position switch that outputs forward, off, and reverse output at the pre-determined frequency.[2] The peak voltage to RMS voltage do not maintain the same relationship as for a sine wave. The DC bus voltage may be actively regulated or the "on" and "off" times can be modified to maintain the same RMS value output up to the DC bus voltage to compensate for DC bus voltage variation.

The ratio of on to off time can be adjusted to vary the RMS voltage while maintaining a constant frequency with a technique called PWM. Harmonic spectrum in the output depends on the width of the pulses and the modulation frequency. When operating induction motors, voltage harmonics is not of great concern, however harmonic distortion in the current waveform introduces additional heating, and can produce pulsating torques.[4]

Numerous electric equipment will operate quite well on modified sine wave power inverter devices, especially any load that is resistive in nature such as a traditional incandescent light bulb.

Most AC motors will run on MSW inverters with an efficiency reduction of about 20% due to the harmonic content.[5]

Other waveforms

By definition there is no restriction on the type of AC waveform an inverter might produce that would find use in a specific or special application.

Output frequency

The AC output frequency of a power inverter device is often the same as the standard power line frequency, for example 60 or 50 cycles per second.

If the output of the device or circuit is to be further conditioned (say stepped up by a follow on transformer) then the frequency may be much higher for good transformer efficiency.

Output voltage

The AC output voltage of a power inverter device is often the same as the standard power line voltage, such as household 120VAC or 240VAC. This allows the inverter to power numerous types of equipment designed to operate off the standard line power.

The designed for output voltage is often provided as a regulated output. That is, changes in the load the inverter is driving will not result in output voltage change from the inverter.

In a sophisticated inverter, the output voltage may be selectable or even continuously variable.

Output power

A power inverter will often have an overall power rating expressed in watts or kilowatts. This describes the power that will be available to the device the inverter is driving and, indirectly, the power that will be needed from the DC source. Smaller popular consumer and commercial devices designed to mimic line power typically range from 150 to 3000 watts.

Not all inverter applications are primarily concerned with brute power delivery, in some cases the frequency and or waveform properties are used by the follow on circuit or device.

Applications

DC power source utilization

An inverter converts the DC electricity from sources such as batteries or fuel cells to AC electricity. The electricity can be at any required voltage; in particular it can operate AC equipment designed for mains operation, or rectified to produce DC at any desired voltage.

Uninterruptible power supplies

An uninterruptible power supply (UPS) uses batteries and an inverter to supply AC power when main power is not available. When main power is restored, a rectifier supplies DC power to recharge the batteries.

Electric motor speed control

Inverter circuits designed to produce a variable output voltage range are often used within motor speed controllers. The DC power for the inverter section can be derived from a normal AC wall outlet or some other source. Control and feedback circuitry is used to adjust the final output of the inverter section which will ultimately determine the speed of the motor operating under its mechanical load. Motor speed control needs are numerous and include things like: industrial motor driven equipment, electric vehicles, rail transport systems, and power tools. (See related: variable-frequency drive )

Power grid

Grid-tied inverters are designed to feed into the electric power distribution system. They transfer synchronously with the line and have as little harmonic content as possible. They also need a means of detecting the presence of utility power for safety reasons, so as not to continue to dangerously feed power to the grid during a power outage.

Solar

A solar inverter can be fed into a commercial electrical grid or used by an off-grid electrical network. Solar inverters have special functions adapted for use with photovoltaic arrays, including maximum power point tracking and anti-islanding protection. Micro-inverters convert direct current from individual solar panels into alternating current for the electric grid. They are grid tie designs by default.

Induction heating

Inverters convert low frequency main AC power to higher frequency for use in induction heating. To do this, AC power is first rectified to provide DC power. The inverter then changes the DC power to high frequency AC power.

HVDC power transmission

With HVDC power transmission, AC power is rectified and high voltage DC power is transmitted to another location. At the receiving location, an inverter in a static inverter plant converts the power back to AC. The inverter must be synchronized with grid frequency and phase and minimize harmonic generation.

Electroshock weapons

Electroshock weapons and tasers have a DC/AC inverter to generate several tens of thousands of V AC out of a small 9 V DC battery. First the 9VDC is converted to 400–2000V AC with a compact high frequency transformer, which is then rectified and temporarily stored in a high voltage capacitor until a pre-set threshold voltage is reached. When the threshold (set by way of an airgap or TRIAC) is reached, the capacitor dumps its entire load into a pulse transformer which then steps it up to its final output voltage of 20–60 kV. A variant of the principle is also used in electronic flash and bug zappers, though they rely on a capacitor-based voltage multiplier to achieve their high voltage.

Circuit description

and automatic equivalent

auto-switching device implemented with two transistors and split winding auto-transformer in place of the mechanical switch.

Basic designs

In one simple inverter circuit, DC power is connected to a transformer through the center tap of the primary winding. A switch is rapidly switched back and forth to allow current to flow back to the DC source following two alternate paths through one end of the primary winding and then the other. The alternation of the direction of current in the primary winding of the transformer produces alternating current (AC) in the secondary circuit.

The electromechanical version of the switching device includes two stationary contacts and a spring supported moving contact. The spring holds the movable contact against one of the stationary contacts and an electromagnet pulls the movable contact to the opposite stationary contact. The current in the electromagnet is interrupted by the action of the switch so that the switch continually switches rapidly back and forth. This type of electromechanical inverter switch, called a vibrator or buzzer, was once used in vacuum tube automobile radios. A similar mechanism has been used in door bells, buzzers and tattoo machines.

As they became available with adequate power ratings, transistors and various other types of semiconductor switches have been incorporated into inverter circuit designs. Certain ratings, especially for large systems (many kilowatts) use thyristors (SCR). SCRS provide large power handling capability in a semiconductor device, and can readily be controlled over a variable firing range.

The switch in the simple inverter described above, when not coupled to an output transformer, produces a square voltage waveform due to its simple off and on nature as opposed to the sinusoidal waveform that is the usual waveform of an AC power supply. Using Fourier analysis, periodic waveforms are represented as the sum of an infinite series of sine waves. The sine wave that has the same frequency as the original waveform is called the fundamental component. The other sine waves, called harmonics, that are included in the series have frequencies that are integral multiples of the fundamental frequency.

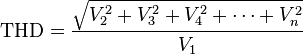

Fourier analysis can be used to calculate the total harmonic distortion (THD). The total harmonic distortion (THD) is the square root of the sum of the squares of the harmonic voltages divided by the fundamental voltage:

Advanced designs

There are many different power circuit topologies and control strategies used in inverter designs. Different design approaches address various issues that may be more or less important depending on the way that the inverter is intended to be used.

The issue of waveform quality can be addressed in many ways. Capacitors and inductors can be used to filter the waveform. If the design includes a transformer, filtering can be applied to the primary or the secondary side of the transformer or to both sides. Low-pass filters are applied to allow the fundamental component of the waveform to pass to the output while limiting the passage of the harmonic components. If the inverter is designed to provide power at a fixed frequency, a resonant filter can be used. For an adjustable frequency inverter, the filter must be tuned to a frequency that is above the maximum fundamental frequency.

Since most loads contain inductance, feedback rectifiers or antiparallel diodes are often connected across each semiconductor switch to provide a path for the peak inductive load current when the switch is turned off. The antiparallel diodes are somewhat similar to the freewheeling diodes used in AC/DC converter circuits.

| waveform | signal transitions per period | harmonics eliminated | harmonics amplified | System Description | THD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | - | - | 2-level square wave | ~45%[3] |

| 4 | 3, 9, 27,... | - | 3-level "modified square wave" | > 23.8%[3] |

| 8 | 5-level "modified square wave" | > 6.5%[3] | ||

| 10 | 3, 5, 9, 27 | 7, 11,... | 2-level very slow PWM | |

| 12 | 3, 5, 9, 27 | 7, 11,... | 3-level very slow PWM |

Fourier analysis reveals that a waveform, like a square wave, that is anti-symmetrical about the 180 degree point contains only odd harmonics, the 3rd, 5th, 7th, etc. Waveforms that have steps of certain widths and heights can attenuate certain lower harmonics at the expense of amplifying higher harmonics. For example, by inserting a zero-voltage step between the positive and negative sections of the square-wave, all of the harmonics that are divisible by three (3rd and 9th, etc.) can be eliminated. That leaves only the 5th, 7th, 11th, 13th etc. The required width of the steps is one third of the period for each of the positive and negative steps and one sixth of the period for each of the zero-voltage steps.[6]

Changing the square wave as described above is an example of pulse-width modulation (PWM). Modulating, or regulating the width of a square-wave pulse is often used as a method of regulating or adjusting an inverter's output voltage. When voltage control is not required, a fixed pulse width can be selected to reduce or eliminate selected harmonics. Harmonic elimination techniques are generally applied to the lowest harmonics because filtering is much more practical at high frequencies, where the filter components can be much smaller and less expensive. Multiple pulse-width or carrier based PWM control schemes produce waveforms that are composed of many narrow pulses. The frequency represented by the number of narrow pulses per second is called the switching frequency or carrier frequency. These control schemes are often used in variable-frequency motor control inverters because they allow a wide range of output voltage and frequency adjustment while also improving the quality of the waveform.

Multilevel inverters provide another approach to harmonic cancellation. Multilevel inverters provide an output waveform that exhibits multiple steps at several voltage levels. For example, it is possible to produce a more sinusoidal wave by having split-rail direct current inputs at two voltages, or positive and negative inputs with a central ground. By connecting the inverter output terminals in sequence between the positive rail and ground, the positive rail and the negative rail, the ground rail and the negative rail, then both to the ground rail, a stepped waveform is generated at the inverter output. This is an example of a three level inverter: the two voltages and ground.[7]

More on achieving a sine wave

Resonant inverters produce sine waves with LC circuits to remove the harmonics from a simple square wave. Typically there are several series- and parallel-resonant LC circuits, each tuned to a different harmonic of the power line frequency. This simplifies the electronics, but the inductors and capacitors tend to be large and heavy. Its high efficiency makes this approach popular in large uninterruptible power supplies in data centers that run the inverter continuously in an "online" mode to avoid any switchover transient when power is lost. (See related: Resonant inverter)

A closely related approach uses a ferroresonant transformer, also known as a constant voltage transformer, to remove harmonics and to store enough energy to sustain the load for a few AC cycles. This property makes them useful in standby power supplies to eliminate the switchover transient that otherwise occurs during a power failure while the normally idle inverter starts and the mechanical relays are switching to its output.

Enhanced quantization

A proposal suggested in Power Electronics magazine utilizes two voltages as an improvement over the common commercialized technology which can only apply DC bus voltage in either directions or turn it off. The proposal adds an additional voltage to this design. Each cycle consists of sequence as: v1, v2, v1, off/pause, -v1, -v2, -v1.[3]

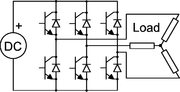

Three phase inverters

Three-phase inverters are used for variable-frequency drive applications and for high power applications such as HVDC power transmission. A basic three-phase inverter consists of three single-phase inverter switches each connected to one of the three load terminals. For the most basic control scheme, the operation of the three switches is coordinated so that one switch operates at each 60 degree point of the fundamental output waveform. This creates a line-to-line output waveform that has six steps. The six-step waveform has a zero-voltage step between the positive and negative sections of the square-wave such that the harmonics that are multiples of three are eliminated as described above. When carrier-based PWM techniques are applied to six-step waveforms, the basic overall shape, or envelope, of the waveform is retained so that the 3rd harmonic and its multiples are cancelled.

To construct inverters with higher power ratings, two six-step three-phase inverters can be connected in parallel for a higher current rating or in series for a higher voltage rating. In either case, the output waveforms are phase shifted to obtain a 12-step waveform. If additional inverters are combined, an 18-step inverter is obtained with three inverters etc. Although inverters are usually combined for the purpose of achieving increased voltage or current ratings, the quality of the waveform is improved as well.

History

Early inverters

From the late nineteenth century through the middle of the twentieth century, DC-to-AC power conversion was accomplished using rotary converters or motor-generator sets (M-G sets). In the early twentieth century, vacuum tubes and gas filled tubes began to be used as switches in inverter circuits. The most widely used type of tube was the thyratron.

The origins of electromechanical inverters explain the source of the term inverter. Early AC-to-DC converters used an induction or synchronous AC motor direct-connected to a generator (dynamo) so that the generator's commutator reversed its connections at exactly the right moments to produce DC. A later development is the synchronous converter, in which the motor and generator windings are combined into one armature, with slip rings at one end and a commutator at the other and only one field frame. The result with either is AC-in, DC-out. With an M-G set, the DC can be considered to be separately generated from the AC; with a synchronous converter, in a certain sense it can be considered to be "mechanically rectified AC". Given the right auxiliary and control equipment, an M-G set or rotary converter can be "run backwards", converting DC to AC. Hence an inverter is an inverted converter.[8]

Controlled rectifier inverters

Since early transistors were not available with sufficient voltage and current ratings for most inverter applications, it was the 1957 introduction of the thyristor or silicon-controlled rectifier (SCR) that initiated the transition to solid state inverter circuits.

The commutation requirements of SCRs are a key consideration in SCR circuit designs. SCRs do not turn off or commutate automatically when the gate control signal is shut off. They only turn off when the forward current is reduced to below the minimum holding current, which varies with each kind of SCR, through some external process. For SCRs connected to an AC power source, commutation occurs naturally every time the polarity of the source voltage reverses. SCRs connected to a DC power source usually require a means of forced commutation that forces the current to zero when commutation is required. The least complicated SCR circuits employ natural commutation rather than forced commutation. With the addition of forced commutation circuits, SCRs have been used in the types of inverter circuits described above.

In applications where inverters transfer power from a DC power source to an AC power source, it is possible to use AC-to-DC controlled rectifier circuits operating in the inversion mode. In the inversion mode, a controlled rectifier circuit operates as a line commutated inverter. This type of operation can be used in HVDC power transmission systems and in regenerative braking operation of motor control systems.

Another type of SCR inverter circuit is the current source input (CSI) inverter. A CSI inverter is the dual of a six-step voltage source inverter. With a current source inverter, the DC power supply is configured as a current source rather than a voltage source. The inverter SCRs are switched in a six-step sequence to direct the current to a three-phase AC load as a stepped current waveform. CSI inverter commutation methods include load commutation and parallel capacitor commutation. With both methods, the input current regulation assists the commutation. With load commutation, the load is a synchronous motor operated at a leading power factor.

As they have become available in higher voltage and current ratings, semiconductors such as transistors or IGBTs that can be turned off by means of control signals have become the preferred switching components for use in inverter circuits.

Rectifier and inverter pulse numbers

Rectifier circuits are often classified by the number of current pulses that flow to the DC side of the rectifier per cycle of AC input voltage. A single-phase half-wave rectifier is a one-pulse circuit and a single-phase full-wave rectifier is a two-pulse circuit. A three-phase half-wave rectifier is a three-pulse circuit and a three-phase full-wave rectifier is a six-pulse circuit.[9]

With three-phase rectifiers, two or more rectifiers are sometimes connected in series or parallel to obtain higher voltage or current ratings. The rectifier inputs are supplied from special transformers that provide phase shifted outputs. This has the effect of phase multiplication. Six phases are obtained from two transformers, twelve phases from three transformers and so on. The associated rectifier circuits are 12-pulse rectifiers, 18-pulse rectifiers and so on...

When controlled rectifier circuits are operated in the inversion mode, they would be classified by pulse number also. Rectifier circuits that have a higher pulse number have reduced harmonic content in the AC input current and reduced ripple in the DC output voltage. In the inversion mode, circuits that have a higher pulse number have lower harmonic content in the AC output voltage waveform.

Other notes

The large switching devices for power transmission applications installed until 1970 predominantly used mercury-arc valves. Modern inverters are usually solid state (static inverters). A modern design method features components arranged in an H bridge configuration. This design is also quite popular with smaller-scale consumer devices.[10][11]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to DC/AC Inverters (power). |

- Electrical power converter

- Rectifier

- Distributed inverter architecture

- Push-pull converter

- Switched-mode power supply (SMPS)

- Space vector modulation

- Variable-frequency drive

References

- ↑ The Authoritative Dictionary of IEEE Standards Terms, Seventh Edition, IEEE Press, 2000,ISBN 0-7381-2601-2, page 588

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 http://www.wpi.edu/Pubs/E-project/Available/E-project-042507-092653/unrestricted/MQP_D_1_2.pdf

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 James, Hahn. "Modifi ed Sine-Wave Inverter Enhanced". Power Electronics.

- ↑ Barnes, Malcolm (2003). Practical variable speed drives and power electronics. Oxford: Newnes. p. 97. ISBN 0080473911.

- ↑ Inverter selection

- ↑ MIT open-courseware, Power Electronics, Spring 2007

- ↑ Rodriguez, Jose; et al. (August 2002). "Multilevel Inverters: A Survey of Topologies, Controls, and Applications". IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics (IEEE) 49 (4): 724–738. doi:10.1109/TIE.2002.801052.

- ↑ Owen, Edward L. (January/February 1996). "Origins of the Inverter". IEEE Industry Applications Magazine: History Department (IEEE) 2 (1): 64–66. doi:10.1109/2943.476602.

- ↑ D. R. Grafham and J. C. Hey, editors, ed. (1972). SCR Manual (Fifth ed.). Syracuse, N.Y. USA: General Electric. pp. 236–239.

- ↑ http://web.eecs.utk.edu/~tolbert/publications/ecce_2011_bailu.pdf

- ↑ http://www05.abb.com/global/scot/scot271.nsf/veritydisplay/369669d5dd6e8e6ec1257ba500293166/$file/70-78%202m315_EN_72dpi.pdf

General references

- Bedford, B. D.; Hoft, R. G. et al. (1964). Principles of Inverter Circuits. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-06134-4.

- Mazda, F. F. (1973). Thyristor Control. New York: Halsted Press Div. of John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-58116-6.

- Dr. Ulrich Nicolai, Dr. Tobias Reimann, Prof. Jürgen Petzoldt, Josef Lutz: Application Manual IGBT and MOSFET Power Modules, 1. Edition, ISLE Verlag, 1998, ISBN 3-932633-24-5 PDF-Version