Potala Palace

| Potala Palace | |

|---|---|

The Potala Palace | |

| Tibetan name | |

| Tibetan | པོ་ཏ་ལ |

| Wylie transliteration | Po ta la |

| official transcription (PRC) | Bodala |

| Chinese name | |

| traditional | 布達拉宮 |

| simplified | 布达拉宫 |

| Pinyin | Bùdálā Gōng |

Potala Palace Location within Tibet

| |

| Coordinates: | 29°39′28″N 91°07′01″E / 29.65778°N 91.11694°E |

| Monastery information | |

| Location | Lhasa, Tibet, China |

| Founded by | Songtsen Gampo |

| Founded | 637 |

| Date renovated |

Modern palace constructed by the 5th Dalai Lama in 1645 Renovated:1989 to 1994, 2002 |

| Type | Tibetan Buddhist |

| Lineage | Dalai Lama |

| Head Lama | 14th Dalai Lama |

| Official name: Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace, Lhasa | |

| Type: | Cultural |

| Criteria: | i, iv, vi |

| Designated: | 1994 (18th session) |

| Reference No. | 707 |

| State Party: | China |

| Region: | Asia-Pacific |

| Extensions: | 2000; 2001 |

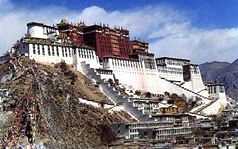

The Potala Palace (Tibetan: པོ་ཏ་ལ, Wylie: Po ta la, ZYPY: Bodala ; simplified Chinese: 布达拉宫; traditional Chinese: 布達拉宮; pinyin: Bùdálā Gōng) in Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region, China, was the chief residence of the Dalai Lama until the 14th Dalai Lama fled to India during the 1959 Tibetan uprising. It is now a museum and UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The palace is named after Mount Potalaka, the mythical abode of Chenresig or Avalokitesvara.[1] Lozang Gyatso, the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, started its construction in 1645[2] after one of his spiritual advisers, Konchog Chophel (died 1646), pointed out that the site was ideal as a seat of government, situated as it is between Drepung and Sera monasteries and the old city of Lhasa.[3] It may overlay the remains of an earlier fortress, called the White or Red Palace,[4] on the site built by Songtsen Gampo in 637.[5]

The building measures 400 metres east-west and 350 metres north-south, with sloping stone walls averaging 3 m. thick, and 5 m. (more than 16 ft) thick at the base, and with copper poured into the foundations to help proof it against earthquakes.[6] Thirteen stories of buildings – containing over 1,000 rooms, 10,000 shrines and about 200,000 statues – soar 117 metres (384 ft) on top of Marpo Ri, the "Red Hill", rising more than 300 m (about 1,000 ft) in total above the valley floor.[7]

Tradition has it that the three main hills of Lhasa represent the "Three Protectors of Tibet." Chokpori, just to the south of the Potala, is the soul-mountain (bla-ri) of Vajrapani, Pongwari that of Manjushri, and Marpori, the hill on which the Potala stands, represents Chenresig or Avalokiteshvara.[8]

History

The site on which the Potala Palace rises is built over a palace erected by Songtsän Gampo on the Red Hill.[9] The Potala contains two chapels on its the northwest corner that conserve parts of the original building. One is the Phakpa Lhakhang, the other the Chogyel Drupuk, a recessed cavern identified as Songtsän Gampo's meditation cave.[10] Lozang Gyatso, the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, started the construction of the modern Potala Palace in 1645[2] after one of his spiritual advisers, Konchog Chophel (died 1646), pointed out that the site was ideal as a seat of government, situated as it is between Drepung and Sera monasteries and the old city of Lhasa.[3] The external structure was built in 3 years, while the interior, together with its furnishings, took 45 years to complete.[11] The Dalai Lama and his government moved into the Potrang Karpo ('White Palace') in 1649.[3] Construction lasted until 1694,[12] some twelve years after his death. The Potala was used as a winter palace by the Dalai Lama from that time. The Potrang Marpo ('Red Palace') was added between 1690 and 1694.[12]

The new palace got its name from a hill on Cape Comorin at the southern tip of India—a rocky point sacred to the bodhisattva of compassion, who is known as Avalokitesvara, or Chenrezi. The Tibetans themselves rarely speak of the sacred place as the "Potala," but rather as "Peak Potala" (Tse Potala), or usually as "the Peak.[13]

The palace was slightly damaged during the Tibetan uprising against the Chinese in 1959, when Chinese shells were launched into the palace's windows. It also escaped damage during the Cultural Revolution in 1966 through the personal intervention of Zhou Enlai,[14] who was then the Premier of the People's Republic of China. Still, almost all of the over 100,000 volumes of scriptures, historical documents and other works of art were either removed, damaged or destroyed.[15]

The Potala Palace was inscribed to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1994. In 2000 and 2001, Jokhang Temple and Norbulingka were added to the list as extensions to the sites. Rapid modernisation has been a concern for UNESCO, however, which expressed concern over the building of modern structures immediately around the palace which threaten the palace's unique atmosphere.[16] The Chinese government responded by enacting a rule barring the building of any structure taller than 21 metres in the area. UNESCO was also concerned over the materials used during the restoration of the palace, which commenced in 2002 at a cost of RMB180 million (US$22.5 million), although the palace's director, Qiangba Gesang, has clarified that only traditional materials and craftsmanship were used. The palace has also received restoration works between 1989 to 1994, costing RMB55 million (US$6.875 million).

The number of visitors to the palace was restricted to 1,600 a day, with opening hours reduced to six hours daily to avoid over-crowding from 1 May 2003. The palace was receiving an average of 1,500 a day prior to the introduction of the quota, sometimes peaking to over 5,000 in one day.[17] Visits to the structure's roof was banned after restoration works were completed in 2006 to avoid further structural damage.[18] Visitorship quotas were raised to 2,300 daily to accommodate a 30% increase in visitorship since the opening of the Qingzang railway into Lhasa on 1 July 2006, but the quota is often reached by mid-morning.[19] Opening hours were extended during the peak period in the months of July to September, where over 6,000 visitors would descend on the site.[20]

Architecture

Built at an altitude of 3,700 m (12,100 ft), on the side of Marpo Ri ('Red Mountain') in the center of Lhasa Valley,[21] the Potala Palace, with its vast inward-sloping walls broken only in the upper parts by straight rows of many windows, and its flat roofs at various levels, is not unlike a fortress in appearance. At the south base of the rock is a large space enclosed by walls and gates, with great porticos on the inner side. A series of tolerably easy staircases, broken by intervals of gentle ascent, leads to the summit of the rock. The whole width of this is occupied by the palace.

The central part of this group of buildings rises in a vast quadrangular mass above its satellites to a great height, terminating in gilt canopies similar to those on the Jokhang. This central member of Potala is called the "red palace" from its crimson colour, which distinguishes it from the rest. It contains the principal halls and chapels and shrines of past Dalai Lamas. There is in these much rich decorative painting, with jewelled work, carving and other ornamentation.

The Chinese Putuo Zongcheng Temple, also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, built between 1767 and 1771, was in part modeled after the Potala Palace. The palace was named by the American television show Good Morning America and newspaper USA Today as one of the "New Seven Wonders".[22]

White Palace

The White Palace or Potrang Karpo is the part of the Potala Palace that makes up the living quarters of the Dalai Lama. The first White Palace was built during the lifetime of the Fifth Dalai Lama and he and his government moved into it in 1649.[3] It then was extended to its size today by the thirteenth Dalai Lama in the early 20th century. The palace was for secular uses and contained the living quarters, offices, the seminary and the printing house. A central, yellow-painted courtyard known as a Deyangshar separates the living quarters of the Lama and his monks with the Red Palace, the other side of the sacred Potala, which is completely devoted to religious study and prayer. It contains the sacred gold stupas—the tombs of eight Dalai Lamas—the monks' assembly hall, numerous chapels and shrines, and libraries for the important Buddhist scriptures, the Kangyur in 108 volumes and the Tengyur with 225. The yellow building at the side of the White Palace in the courtyard between the main palaces houses giant banners embroidered with holy symbols which hung across the south face of the Potala during New Year festivals.

Red Palace

The Red Palace or Potrang Marpo is part of the Potala palace that is completely devoted to religious study and Buddhist prayer. It consists of a complicated layout of many different halls, chapels and libraries on many different levels with a complex array of smaller galleries and winding passages:

Great West Hall

The main central hall of the Red Palace is the Great West Hall which consists of four great chapels that proclaim the glory and power of the builder of the Potala, the Fifth Dalai Lama. The hall is noted for its fine murals reminiscent of Persian miniatures, depicting events in the fifth Dalai Lama's life. The famous scene of his visit to Emperor Shun Zhi in Beijing is located on the east wall outside the entrance. Special cloth from Bhutan wraps the Hall's numerous columns and pillars.

The Saint's Chapel

On the north side of this hall in the Red Palace is an important shrine of the Potala. The chapel like the Dharma cave below it dates from the 7th century. It contains a small ancient jewel encrusted statue of Avalokiteshvara and two of his attendants. On the floor below, a low, dark passage leads into the Dharma Cave where Songsten Gampo is believed to have studied Buddhism. In the holy cave are images of Songsten Gampo, his wives, his chief minister and Sambhota, the scholar who developed Tibetan writing in the company of his many divinities. A large blue and gold inscription over the door was written by the 19th century Tongzhi Emperor of the Qing Empire, proclaiming Buddhism a Blessed Field of Wonderful Fruit.

North Chapel

The North Chapel centres on a crowned Sakyamuni Buddha on the left and the Fifth Dalai Lama on the right seated on magnificent gold thrones. Their equal height and shared aura implies equal status. On the far left of the chapel is the gold stupa tomb of the Eleventh Dalai Lama who died as a child, with rows of benign Medicine Buddhas who were the heavenly healers. On the right of the chapel are Avalokiteshvara and his historical incarnations including Songsten Gampo and the first four Dalai Lamas. Scriptures covered in silk between wooden covers form a specialized library in a room branching off it.

South Chapel

The South Chapel centres on Padmasambhava, the 8th century Indian magician and saint. His consort Yeshe Tsogyal, a gift from the King is by his left knee and his other wife from his native land of Swat is by his right. On his left, eight of his holy manifestations meditate with an inturned gaze. On his right, eight wrathful manifestations wield instruments of magic powers to subdue the demons of the Bön faith.

East Chapel

The East chapel is dedicated to Tsong Khapa, founder of the Gelug tradition. His central figure is surrounded by lamas from Sakya Monastery who had briefly ruled Tibet and formed their own tradition until converted by Tsong Khapa. Other statues are displayed made of various different materials and display noble expressions.

West Chapel

This is the chapel that contains the five golden stupas. The enormous central stupa, 14.85 metres (49 ft) high, contains the mummified body of the Fifth Dalai Lama. This stupa is built of sandalwood and is remarkably coated in 3,727 kg (8,200 lb) of solid gold and studded with 18,680 pearls and semi-precious jewels.[23] On the left is the funeral stupa for the Twelfth Dalai Lama and on the right that of the Tenth Dalai Lama. The nearby stupa for the 13th Dalai Lama is 22 metres (72 ft) high. The stupas on both ends contain important scriptures.[7]

First Gallery

The first gallery is on the floor above the West chapel and has a number of large windows that give light and ventilation to the Great West Hall and its chapels below. Between the windows, superb murals show the Potala's construction is fine detail.

Second Gallery

The Second Gallery gives access to the central pavilion which is used for visitors to the palace for refreshments and to buy souvenirs.

Third Gallery

The Third Gallery besides fine murals has a number of dark rooms branching off it containing enormous collections of bronze statues and miniature figures made of copper and gold worth a fortune. The chanting hall of the Seventh Dalai Lama is on the south side and on the east an entrance connects the section to the Saints chapel and the Deyangshar between the two palaces.

Tomb of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama

The tomb of the 13th Dalai Lama is located west of the Great West Hall and it can be reached only from an upper floor and with the company of a monk or a guide of the Potala. Built in 1933, the giant stupa contains priceless jewels and one ton of solid gold. It is 14 metres (46 ft) high. Devotional offerings include elephant tusks from India, porcelain lions and vases and a mandala made from over 200,000 pearls. Elaborate murals in traditional Tibetan styles depict many events of the life of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama during the early 20th century.

The Lhasa Zhol Pillars

Lhasa Zhol Village has two stone pillars or rdo-rings, an interior stone pillar or doring nangma, which stands within the village fortification walls, and the exterior stone pillar or doring chima,[24] which originally stood outside the South entrance to the village. Today the pillar stands neglected to the East of the Liberation Square, on the South side of Beijing Avenue.

The doring chima dates as far back as c. 764, "or only a little later,"[25] and is inscribed with what may be the oldest known example of Tibetan writing.[26]

The pillar contains dedications to a famous Tibetan general and gives an account of his services to the king including campaigns against China which culminated in the brief capture of the Chinese capital Chang'an (modern Xian) in 763[27] during which the Tibetans temporarily installed as Emperor a relative of Princess Jincheng Gongzhu (Kim-sheng Kong co), the Chinese wife of Trisong Detsen's father, Me Agtsom.[28][29]

See also

- Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama's former summer palace

- Jokhang Temple Monastery

- Dhvaja

- Kundun, a 1997 film about the Dalai Lama, chiefly set inside the palace

- Seven Years in Tibet

- Leh Palace

- Mount Putuo

Footnotes

- ↑ Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization (1962). Translated into English with minor revisions by the author. 1st English edition by Faber & Faber, London (1972). Reprint: Stanford University Press (1972), p. 84

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Laird, Thomas. (2006). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama, pp. 175. Grove Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Karmay, Samten C. (2005). "The Great Fifth", p. 1. Downloaded as a pdf file on 16 December 2007 from:

- ↑ W. D. Shakabpa, One hundred thousand moons, translated with an introduction by Derek F. Maher, Vol.1, BRILL, 2010 p.48

- ↑ Michael Dillon, China : a cultural and historical dictionary, Routledge, 1998, p.184.

- ↑ Booz, Elisabeth B. (1986). Tibet, pp. 62-63. Passport Books, Hong Kong.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Buckley, Michael and Strausss, Robert. Tibet: a travel survival kit, p. 131. Lonely Planet. South Yarra, Vic., Australia. ISBN 0-908086-88-1.

- ↑ Stein, R. A. (1972). Tibetan Civilization, p. 228. Translated by J. E. Stapleton Driver. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 (paper).

- ↑ Derek F. Maher in W. D. Shakabpa, One hundred thousand moons, translated with an introduction by Derek F. Maher, BRILL, 2010,Vol. 1,p.123.

- ↑ Gyurme Dorje, Tibet handbook: with Bhutan, Footprint Travel Guides, 1999 pp.101-3.

- ↑ W. D. Shakabpa, One hundred thousand moons, translated with an introduction by Derek F. Maher BRILL, 2010, Vol.1, pp.48-9.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization (1962). Translated into English with minor revisions by the author. 1st English edition by Faber & Faber, London (1972). Reprint: Stanford University Press (1972), p. 84.

- ↑ Lowell Thomas, Jr. (1951). Out of this World: Across the Himalayas to Tibet'. Reprint: 1952, p. 181. Macdonald & Co., London

- ↑ http://www.potalarestaurante.com/potala.php

- ↑ Decline of Potala par Oser

- ↑ "Development 'not ruining' Potala". BBC News. 28 July 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ Tourist entry restriction protects Potala Palace

- ↑ Potala Palace bans roof tour

- ↑ Tibet's Potala Palace to restrict visitors to 2,300 a day

- ↑ Tibet bans price rises at all tourist sites(05/04/07)

- ↑ Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization (1962). Translated into English with minor revisions by the author. 1st English edition by Faber & Faber, London (1972). Reprint: Stanford University Press (1972), p. 206

- ↑ ABC Good Morning America "7 New Wonders" Page

- ↑ Chorten of the fifth Dalai Lama in the Potala Palace in Lhasa of Tibet Autonomous Region

- ↑ Larsen and Sinding-Larsen (2001), p. 78.

- ↑ Richardson (1985), p. 2.

- ↑ Coulmas, Florian (1999). "Tibetan writing". Blackwell Reference Online. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Snellgrove and Richardson (1995), p. 91.

- ↑ Richardson (1984), p. 30.

- ↑ Beckwith (1987), p. 148.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press- Beckwith, Christopher I. (1987). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 0-691-02469-3.

- "Reading the Potala." Peter Bishop. In: Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places In Tibetan Culture: A Collection of Essays. (1999) Edited by Toni Huber, pp. 367–388. The Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, H.P., India. ISBN 81-86470-22-0.

- Das, Sarat Chandra. Lhasa and Central Tibet. (1902). Edited by W. W. Rockhill. Reprint: Mehra Offset Press, Delhi (1988), pp. 145–146; 166-169; 262-263 and illustration opposite p. 154.

- Larsen and Sinding-Larsen (2001). The Lhasa Atlas: Traditional Tibetan Architecture and Landscape, Knud Larsen and Amund Sinding-Larsen. Shambhala Books, Boston. ISBN 1-57062-867-X.

- Richardson, Hugh E. (1984) Tibet & Its History. 1st edition 1962. Second Edition, Revised and Updated. Shambhala Publications. Boston ISBN 0-87773-376-7.

- Richardson, Hugh E. (1985). A Corpus of Early Tibetan Inscriptions. Royal Asiatic Society. ISBN 0-94759300-4.

- Snellgrove, David & Hugh Richardson. (1995). A Cultural History of Tibet. 1st edition 1968. 1995 edition with new material. Shambhala. Boston & London. ISBN 1-57062-102-0.

- von Schroeder, Ulrich. (1981). Indo-Tibetan Bronzes. (608 pages, 1244 illustrations). Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications Ltd. ISBN 962-7049-01-8

- von Schroeder, Ulrich. (2001). Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet. Vol. One: India & Nepal; Vol. Two: Tibet & China. (Volume One: 655 pages with 766 illustrations; Volume Two: 675 pages with 987 illustrations). Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd. ISBN 962-7049-07-7

- von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2008. 108 Buddhist Statues in Tibet. (212 p., 112 colour illustrations) (DVD with 527 digital photographs). Chicago: Serindia Publications. ISBN 962-7049-08-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Potala Palace. |

Potala Palace travel guide from Wikivoyage

Potala Palace travel guide from Wikivoyage- Potala Palace (Unesco)

- Potala (Tibetan and Himalayan Digital Library)

- Research work on possible relation with Potala, Malaya Mountains and South India

- Research work on Buddhism in India

- Google Maps location of Potala Palace

- Three dimensional rendering of Potala Palace (without plugin; in English, Spanish, German)

Coordinates: 29°39′28″N 91°07′01″E / 29.65778°N 91.11694°E

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||