Portuguese language

| Portuguese | |

|---|---|

| português | |

| Native to | See geographic distribution of Portuguese |

Native speakers | 240 million (2013)[1] |

|

Indo-European

| |

Early forms |

Medieval Galician

|

|

Latin (Portuguese alphabet) Portuguese Braille | |

| Signed Portuguese | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

9 countries

1 dependency

Cultural language

|

| Regulated by |

International Portuguese Language Institute Academia Brasileira de Letras (Brazil) Academia das Ciências de Lisboa, Classe de Letras (Portugal) CPLP |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | pt |

| ISO 639-2 | por |

| ISO 639-3 | por |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-a |

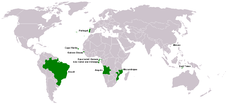

Native language

Official and administrative language

Cultural or secondary language

Portuguese speaking minorities

| |

Portuguese (português or língua portuguesa [ˈɫĩɡwɐ puɾtuˈɣezɐ][2]) is a Romance language and the sole official language of Portugal, Brazil, Mozambique, Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, and São Tomé and Príncipe.[3] It also has co-official language status in Macau, Equatorial Guinea and East Timor. As the result of expansion during colonial times, Portuguese speakers are also found in Goa, Daman and Diu in India,[4] and in Malacca in Malaysia.

Portuguese is a part of the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several dialects of colloquial Latin in the medieval Kingdom of Galicia. With approximately 210 to 215 million native speakers and 240 million total speakers, Portuguese is usually listed as the seventh most spoken language in the world (or sixth, being very close to Bengali in native speakers), the third most spoken European language[5] and the major language of the Southern Hemisphere. It is also the most spoken language in South America and the second most spoken in Latin America, after Castilian, as well as an official language of the European Union and Mercosul.

Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes once called Portuguese "the sweet and gracious language" and Spanish playwright Lope de Vega referred to it as "sweet", while the Brazilian writer Olavo Bilac poetically described it as "a última flor do Lácio, inculta e bela" (the last flower of Latium, rustic and beautiful). Portuguese is also termed "the language of Camões", after one of the greatest literary figures in the Portuguese language, Luís Vaz de Camões.[6][7][8]

In March 2006, the Museum of the Portuguese Language, an interactive museum about the Portuguese language, was founded in São Paulo, Brazil, the city with the greatest number of Portuguese language speakers in the world.[9]

History

When the Romans arrived in the Iberian Peninsula in 216 BC, they brought the Latin language with them, from which all Romance languages descend. The language was spread by arriving Roman soldiers, settlers, and merchants, who built Roman cities mostly near the settlements of previous civilizations.

Between AD 409 and 711, as the Roman Empire collapsed in Western Europe, the Iberian Peninsula was conquered by Germanic peoples (Migration Period). The occupiers, mainly Suebi and Visigoths, quickly adopted late Roman culture and the Vulgar Latin dialects of the peninsula. After the Moorish invasion of 711, Arabic became the administrative and common language in the conquered regions, but most of the remaining Christian population continued to speak a form of Romance commonly known as Mozarabic which lasted a couple of centuries longer in Spain. The influence exerted by Arabic on the different Romance dialects spoken in the Christian kingdoms, and in Portugal in particular; was mainly restricted to affecting some of the lexicon.

| Medieval Portuguese poetry |

|---|

| Das que vejo |

| nom desejo |

| outra senhor se vós nom, |

| e desejo |

| tam sobejo, |

| mataria um leon, |

| senhor do meu coraçom: |

| fim roseta, |

| bela sobre toda fror, |

| fim roseta, |

| nom me meta |

| em tal coita voss'amor! |

| João Lobeira (c. 1270–1330) |

Portuguese evolved from the medieval language, known today by linguists as Galician-Portuguese or Old Portuguese or Old Galician, of the northwestern medieval Kingdom of Galicia, the first among the Christian kingdoms after the start of the Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula from the Moors. It is in Latin administrative documents of the 9th century that written Galician-Portuguese words and phrases are first recorded. This phase is known as Proto-Portuguese, which lasted from the 9th century until the 12th-century independence of the County of Portugal from the Kingdom of Galicia, then a subkingdom of León.

In the first part of Galician-Portuguese period (from the 12th to the 14th century), the language was increasingly used for documents and other written forms. For some time, it was the language of preference for lyric poetry in Christian Hispania, much as Occitan was the language of the poetry of the troubadours in France. Portugal became an independent kingdom in 1139, under King Afonso I of Portugal. In 1290, King Denis of Portugal created the first Portuguese university in Lisbon (the Estudos Gerais, later moved to Coimbra) and decreed that Portuguese, then simply called the "common language", be known as the Portuguese language and used officially.

In the second period of Old Portuguese, in the 15th and 16th centuries, with the Portuguese discoveries, the language was taken to many regions of Africa, Asia and the Americas. The great majority of Portuguese speakers now live in Brazil, Portugal's biggest former colony. By the mid-16th century Portuguese had become a lingua franca in Asia and Africa, used not only for colonial administration and trade but also for communication between local officials and Europeans of all nationalities.

Its spread was helped by mixed marriages between Portuguese and local people, and by its association with Roman Catholic missionary efforts, which led to the formation of creole languages such as that called Kristang in many parts of Asia (from the word cristão, "Christian"). The language continued to be popular in parts of Asia until the 19th century. Some Portuguese-speaking Christian communities in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia preserved their language even after they were isolated from Portugal.

The end of the Old Portuguese period was marked by the publication of the Cancioneiro Geral by Garcia de Resende, in 1516. The early times of Modern Portuguese, which spans a period from the 16th century to the present day, were characterized by an increase in the number of learned words borrowed from Classical Latin and Classical Greek since the Renaissance, which greatly enriched the lexicon.

Geographic distribution

Portuguese is the language of the majority of people in Brazil,[10] Portugal,[11] and São Tomé and Príncipe (95%).[12] Portuguese is quickly becoming the predominant native language of Angola. According to figures from 1983, roughly 70%, perhaps more, of Angolans speak Portuguese natively, and 80% profess fluency in Portuguese.[13][14] Although only just over 10 percent of the population are native speakers of Portuguese in Mozambique, the language is spoken by about 50.4 percent there according to the 2007 census.[15] It is also spoken by 11.5 percent of the population in Guinea-Bissau.[16] No data is available for Cape Verde, but almost all the population is bilingual, and the monolingual population speaks Cape Verdean Creole.

There are also significant Portuguese-speaking immigrant communities in many countries including Andorra (15.4%),[17] Australia,[18] Bermuda,[19] Canada (0.72% or 219,275 persons in the 2006 census[20] but between 400,000 and 500,000 according to Nancy Gomes),[21] Curaçao, France,[22] Japan,[23] Jersey,[24] Luxembourg (9%),[11] Namibia (about 4-5% of the population, mainly refugees from Angola in the North of the country)[25] Paraguay (10.7% or 636,000 persons),[26] Macau (0.6% or 12,000 persons),[27] South Africa,[28] Switzerland (196,000 nationals in 2008),[29] Venezuela (1 to 2% or 254,000 to 480,000),[30] and the USA (0.24% of the population or 687,126 speakers according to the 2007 American Community Survey),[31] mainly in Connecticut,[32] Florida,[33] Massachusetts (where it is the second most spoken language in the state),[34] New Jersey,[35] New York[36] and Rhode Island.[37]

In some parts of the former Portuguese India i.e. Goa,[38] Daman and Diu,[39] the language is still spoken.

Official status

The Community of Portuguese Language Countries[3] (with the Portuguese acronym CPLP) consists of the eight independent countries that have Portuguese as an official language: Angola, Brazil, Cape Verde, East Timor, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Portugal and São Tomé and Príncipe.[3]

Equatorial Guinea made a formal application for full membership to the CPLP in June 2010 and should add Portuguese as its third official language (alongside Spanish and French) since this is one of the conditions. The President of Equatorial Guinea, Obiang Nguema Mbasog, and Prime Minister Ignacio Milam Tang have approved on 20 July 2011 the new Constitutional bill that intends to add Portuguese as an official language of the country. The bill is now waiting for ratification by the People's Representative Chamber and it shall come into force 20 days after its publication at the official state's gazette.[40][41][42]

Portuguese is also one of the official languages of the Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China of Macau (alongside Chinese) and of several international organizations, including the Mercosur,[43] the Organization of Ibero-American States,[44] the Union of South American Nations,[45] the Organization of American States,[46] the African Union[47] and the European Union.[48]

Population of countries and jurisdictions of Portuguese official or co-official language

According to The World Factbook country population estimates for 2013, the population of each of the nine jurisdictions is as follows (by descending order):

| Country | Population (2013 est.)[49] |

|---|---|

| | 201,009,622 |

| | 24,096,669 |

| | 18,565,269 |

| | 10,799,270 |

| | 1,660,870 |

| | 1,172,390 |

| | 583,003 |

| | 531,046 |

| | 186,817 |

| Total | 258,604,956 |

This means that the population living in the Lusophone official area is of 258,604,956 inhabitants. To this number there is yet to add the Lusophone diaspora spread throughout the world, estimated at little less than 10 million people (4.5 million Portuguese, 3 million Brazilians, half a million Cape Verdeans, etc.) although it is hard to obtain official accurate numbers — including the percentage of this diaspora that can actually speak Portuguese, because a significant portion of these citizens are naturalized citizens born outside of Lusophone territory or children of immigrants, and who may have only the most basic command of the language. It is also important to note that a big part of these national diasporas is a part of the already counted population of the Portuguese-speaking countries and territories, like the high number of Brazilian and PALOP emigrant citizens in Portugal or the high number of Portuguese emigrant citizens in the PALOP and Brazil.

The Portuguese language therefore serves more than 250 million people daily, who have direct or indirect legal, juridic and social contact with it, varying from the only language used in any contact, to only education, contact with local or international administration, commerce and services or the simple sight of road signs, public information and advertising in Portuguese.

Portuguese as a foreign language

The mandatory offering of Portuguese language in school curricula is observed in Uruguay[50] and Argentina.[51] Other countries where Portuguese is taught at schools or is being introduced now include Venezuela,[52] Zambia,[53] Congo,[54] Senegal,[54] Namibia,[25] Swaziland,[54] and South Africa.[54]

Future

According to estimates by UNESCO, Portuguese and Spanish are the fastest-growing European languages after English and the language has, according to the newspaper The Portugal News publishing data given from UNESCO, the highest potential for growth as an international language in southern Africa and South America.[55] The Portuguese-speaking African countries are expected to have a combined population of 83 million by 2050. In total, the Portuguese-speaking countries will have about 400 million people by the same year.[55]

Since 1991, when Brazil signed into the economic community of Mercosul with other South American nations, such as Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay, there has been an increase in interest in the study of Portuguese in those South American countries.

Although early in the 21st century, after Macau was ceded to China and Brazilian immigration to Japan slowed down, the use of Portuguese was in decline in Asia, it is once again becoming a language of opportunity there, mostly because of increased diplomatic and financial ties with Portuguese-speaking countries in China,[56] but also some interest in their cultures, mainly Koreans and Japanese about Brazil.

Dialects

Modern Standard European Portuguese (português padrão) is based on the Portuguese spoken in the area including and surrounding the cities of Coimbra and Lisbon, in central Portugal, while modern Standard Brazilian Portuguese (português neutro) is based on the Portuguese spoken in the area including and surrounding the city of Rio de Janeiro, in southeastern Brazil,[57][58] which if vanished from its stereotypical traits i.e. its strong European flavor in phonology and prosody, is linguistically a halfway between Brazilian dialects and accents.

Standard European Portuguese is also the preferred standard by the Portuguese-speaking African countries. As such, and despite the fact that its speakers are dispersed around the world, Portuguese has only two dialects used for learning: the European and the Brazilian. Some aspects and sounds found in many dialects of Brazil are exclusive to South America, and can not be found in Europe. However, the Santomean Portuguese in Africa may be confused with a Brazilian dialect by its phonology and prosody. Some aspects link some Brazilian dialects with the ones spoken in Africa, such as the pronunciation of "menino", which is pronounced as [miˈninu] (though rather different for many Brazilian speakers, e.g. [me̞ˈn̠ʲĩnʊ]) compared to [mɯ̟ˈninu] in European Portuguese, though most of them are assumed to be conservative rather than innovative. Dialects from inland northern Portugal have significant similarities with Galician.

Audio samples of some dialects and accents of Portuguese are available below.[59] There are some differences between the areas but these are the best approximations possible. IPA transcriptions refer to the names in local pronunciation.

Angola

- Benguelense—Benguela province.

-

Luandense—Luanda province.

Luandense—Luanda province. - Sulista—South of Angola.

- Huambense—Huambo province.

Brazil

- Caipira [kajˈpiɽɐ] — Spoken in the states of São Paulo (most markedly on the countryside and rural areas); southern Minas Gerais, northern Paraná and southeastern Mato Grosso do Sul. Depending on the vision of what constitutes caipira, Triângulo Mineiro, border areas of Goiás and the remaining parts of Mato Grosso do Sul are included, and the frontier of caipira in Minas Gerais is expanded further northerly, though not reaching metropolitan Belo Horizonte. It is often said that caipira appeared by decreolization of the língua brasílica and the related língua geral paulista, then spoken in almost all of what is now São Paulo, a former lingua franca in most of the contemporary Centro-Sul of Brazil before the 18th century, brought by the bandeirantes, interior pioneers of Colonial Brazil, closely related to its northern counterpart Nheengatu, and that is why the dialect shows many general differences from other variants of the language.[60] It has striking remarkable differences in comparison to other Brazilian dialects in phonology, prosody and grammar, often stigmatized as being strongly associated with a substandard variant, now mostly rural.[61][62][63][64][65]

- Cearense or costa norte — is a dialect spoken more sharply in the states of Ceará and Piauí. The variant of Ceará includes fairly distinctive traits it shares with the one spoken in Piauí, though, such as distinctive regional phonology and vocabulary (for example, a debuccalization process stronger than that of Portuguese, a different system of the vowel harmony that spans Brazil from fluminense and mineiro to amazofonia but is especially prevalent in nordestino, a very coherent coda sibilant palatalization as those of Portugal and Rio de Janeiro but allowed in less environments than in other accents of nordestino, a greater presence of dental stop palatalization to palato-alveolar and especially alveolo-palatal in comparison to other accents of nordestino, among others, as well as a great number of archaic Portuguese words).[66][67][68][69][70][71]

- Baiano — Found in Bahia, Sergipe, northern Minas Gerais and border regions with Goiás and Tocantins. Similar to nordestino, it has a very characteristic syllable-timed rhythm and the greatest tendency to pronounce unstressed mid vowels [e̞] and [o̞] as open-mid [ɛ] and [ɔ].

Variants and sociolects of Brazilian Portuguese.

Variants and sociolects of Brazilian Portuguese. -

Fluminense — A broad dialect with many variants spoken in the states of Rio de Janeiro, Espírito Santo and neighbouring eastern regions of Minas Gerais. Fluminense formed in these previously caipira-speaking areas due to the gradual influence of European migrants, causing many people to distance their speech from their original dialect and incorporate new terms.[72] Fluminense is sometimes referred to as carioca, however carioca is a more specific term referring to the accent of the Greater Rio de Janeiro area by speakers with a fluminense dialect.

Fluminense — A broad dialect with many variants spoken in the states of Rio de Janeiro, Espírito Santo and neighbouring eastern regions of Minas Gerais. Fluminense formed in these previously caipira-speaking areas due to the gradual influence of European migrants, causing many people to distance their speech from their original dialect and incorporate new terms.[72] Fluminense is sometimes referred to as carioca, however carioca is a more specific term referring to the accent of the Greater Rio de Janeiro area by speakers with a fluminense dialect. - Gaúcho — [ɡaˈuʃʊ], in Rio Grande do Sul, similar to sulista. There are many distinct accents in Rio Grande do Sul, mainly due to the heavy influx of European immigrants of diverse origins who have settled in colonies throughout the state, and to the proximity to Spanish-speaking nations. The gaúcho word in itself is a Spanish loanword into Portuguese of obscure Indigenous Amerindian origins.

Percentage of worldwide Portuguese speakers per country.

Percentage of worldwide Portuguese speakers per country. - Mineiro — [miˈneːɽʷ], Minas Gerais (not prevalent in the Triângulo Mineiro). As the fluminense area, its associated region was formerly a sparsely populated land where caipira was spoken, but the discovery of gold and gems made it the most prosperous Brazilian region, what attracted Portuguese colonists, commoners from other parts of Brazil and their African slaves. South-southwestern, southeastern and northern areas of the state have fairly distinctive speech, actually approximating to caipira, fluminense (popularly called, often pejoratively, carioca do brejo, "marsh carioca") and baiano respectively. Areas including and surrounding Belo Horizonte have a distinctive accent.

-

Nordestino[73] — [nɔɦdɛʃˈtĩnu], more marked in the Sertão (7), where, in the 19th and 20th centuries and especially in the area including and surrounding the sertão (the dryland after Agreste) of Pernambuco and southern Ceará, it could sound less comprehensible to speakers of other Portuguese dialects than Galician or Rioplatense Spanish, and nowadays less distinctive from other variants in the metropolitan cities along the coasts. It can be divided in two regional variants, one that includes the northern Maranhão and southern of Piauí, and other that goes from Ceará to Alagoas.

Nordestino[73] — [nɔɦdɛʃˈtĩnu], more marked in the Sertão (7), where, in the 19th and 20th centuries and especially in the area including and surrounding the sertão (the dryland after Agreste) of Pernambuco and southern Ceará, it could sound less comprehensible to speakers of other Portuguese dialects than Galician or Rioplatense Spanish, and nowadays less distinctive from other variants in the metropolitan cities along the coasts. It can be divided in two regional variants, one that includes the northern Maranhão and southern of Piauí, and other that goes from Ceará to Alagoas. - Nortista [nɔxˈtɕiɕtɐ] or amazofonia — Most of Amazon Basin states i.e. Northern Brazil. Before the 20th century, most people from the nordestino area fleeing the droughts and their associated poverty settled here, so it has some similarities with the Portuguese dialect there spoken. The speech in and around the city of Belém has a more European flavor in phonology, prosody and grammar.

- Paulistano — Variants spoken around Greater São Paulo in its maximum definition and more easterly areas of São Paulo state, as well perhaps "educated speech" from anywhere in the state of São Paulo (where it coexists with caipira). Caipira is the hinterland sociolect of much of the Central-Southern half of Brazil, nowadays conservative only in the rural areas and associated with them, that has a historically low prestige in cities as Rio de Janeiro, Curitiba, Belo Horizonte, and until some years ago, in São Paulo itself. Sociolinguistics, or what by times is described as 'linguistic prejudice', often correlated with classism,[74][75][76] is a polemic topic in the entirety of the country since the times of Adoniran Barbosa. Also, the "Paulistano" accent was heavily influenced by the presence of immigrants in the city of São Paulo, especially the Italians.

- Sertanejo — Center-Western states, and also much of Tocantins and Rondônia. It is closer to mineiro, caipira, nordestino or nortista depending on the location.

- Sulista — The variants spoken in the areas between the northern regions of Rio Grande do Sul and southern regions of São Paulo state, encompassing most of southern Brazil. The city of Curitiba does have a fairly distinct accent as well, and a relative majority of speakers around and in Florianópolis also speak this variant (many speak florianopolitano or manezinho da ilha instead, related to the European Portuguese dialects spoken in Azores and Madeira). Speech of northern Paraná is closer to that of inland São Paulo.

- Florianopolitano — Variants heavily influenced by European Portuguese spoken in Florianópolis city (due to a heavy immigration movement from Portugal, mainly its insular regions) and much of its metropolitan area, Grande Florianópolis, said to be a continuum between those whose speech most resemble sulista dialects and those whose speech most resemble fluminense and European ones, called, often pejoratively, manezinho da ilha.

- Carioca — Not a dialect, but sociolects of the fluminense variant spoken in an area roughly corresponding to Greater Rio de Janeiro. It appeared after locals came in contact with the Portuguese aristocracy amidst the Portuguese royal family fled in the early 19th century. There is actually a continuum between Vernacular countryside accents and the carioca sociolect, and the educated speech (in Portuguese norma culta, which most closely resembles other Brazilian Portuguese standards but with marked recent Portuguese influences, the nearest ones among the country's dialects along florianopolitano), so that not all people native to the state of Rio de Janeiro speak the said sociolect, but most carioca speakers will use the standard variant not influenced by it that is rather uniform around Brazil depending on context (emphasis or formality, for example).

- Brasiliense — used in Brasília and its metropolitan area.[77] It is not considered a dialect, but more of a regional variant – often deemed to be closer to fluminense than the dialect commonly spoken in most of Goiás, sertanejo.

- Arco do desflorestamento or serra amazônica — Known in its region as the "accent of the migrants", it has similarities with caipira, sertanejo and often sulista that make it differing from amazofonia (in the opposite group of Brazilian dialects, in which it is placed along nordestino, baiano, mineiro and fluminense). It is the most recent dialect, which appeared by the settlement of families from various other Brazilian regions attracted by the cheap land offer in recently deforested areas.[78][79]

- Recifense — used in Recife and its metropolitan area.

Portugal

-

Micaelense (Açores) (São Miguel)—Azores.

Micaelense (Açores) (São Miguel)—Azores. -

Alentejano—Alentejo (Alentejan Portuguese)

Alentejano—Alentejo (Alentejan Portuguese) -

Algarvio—Algarve (there is a particular dialect in a small part of western Algarve).

Algarvio—Algarve (there is a particular dialect in a small part of western Algarve). -

Alto-Minhoto—North of Braga (hinterland).

Alto-Minhoto—North of Braga (hinterland). -

Baixo-Beirão; Alto-Alentejano—Central Portugal (hinterland).

Baixo-Beirão; Alto-Alentejano—Central Portugal (hinterland). -

Beirão— Central Portugal.

Beirão— Central Portugal. -

Estremenho—Regions of Coimbra, Leiria and Lisbon (this is a disputed denomination, as Coimbra is not part of "Estremadura", and the Lisbon dialect has some peculiar features that not only are not shared with the one of Coimbra, as make it significantly distinct and recognizable to most native speakers from elsewhere in Portugal).

Estremenho—Regions of Coimbra, Leiria and Lisbon (this is a disputed denomination, as Coimbra is not part of "Estremadura", and the Lisbon dialect has some peculiar features that not only are not shared with the one of Coimbra, as make it significantly distinct and recognizable to most native speakers from elsewhere in Portugal). -

Madeirense (Madeiran)—Madeira.

Madeirense (Madeiran)—Madeira. -

Nortenho—Regions of the districts of Braga, Porto and parts of Aveiro.

Nortenho—Regions of the districts of Braga, Porto and parts of Aveiro. -

Transmontano—Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro.

Transmontano—Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro.

Other countries

-

Cape Verde—

Cape Verde— Português cabo-verdiano (Cape Verdean Portuguese)

Português cabo-verdiano (Cape Verdean Portuguese) -

Guinea-Bissau—

Guinea-Bissau— Guineense (Guinean Portuguese)

Guineense (Guinean Portuguese) -

India — Damaense (Damanese Portuguese) and Goês (Goan Portuguese)

India — Damaense (Damanese Portuguese) and Goês (Goan Portuguese) -

Macau—

Macau— Macaense (Macanese Portuguese)

Macaense (Macanese Portuguese) -

Mozambique—

Mozambique— Moçambicano (Mozambican Portuguese)

Moçambicano (Mozambican Portuguese) -

São Tomé and Príncipe—

São Tomé and Príncipe— Santomense (São Tomean Portuguese)

Santomense (São Tomean Portuguese) -

Spain—Oliventian Portuguese and other varieties sometimes controversially deemed as separate languages, such as Galician and Fala.

Spain—Oliventian Portuguese and other varieties sometimes controversially deemed as separate languages, such as Galician and Fala. -

Uruguay—Dialectos Portugueses del Uruguay (DPU)

Uruguay—Dialectos Portugueses del Uruguay (DPU) -

Timor-Leste—

Timor-Leste— Timorense (East Timorese Portuguese)

Timorense (East Timorese Portuguese)

Differences between dialects are mostly of accent and vocabulary, but between the Brazilian dialects and other dialects, especially in their most colloquial forms, there can also be some grammatical differences. The Portuguese-based creoles spoken in various parts of Africa, Asia, and the Americas are independent languages.

Characterization and peculiarities

Portuguese, like Catalan and Sardinian, preserved the stressed vowels of Vulgar Latin, which became diphthongs in most other Romance languages; cf. Port., Cat., Sard. pedra ; Fr. pierre, Sp. piedra, It. pietra, Ro. piatră, from Lat. petram ("stone"); or Port. fogo, Cat. foc, Sard. fogu; Sp. fuego, It. fuoco, Fr. feu, Ro. foc, from Lat. focus ("fire"). Another characteristic of early Portuguese was the loss of intervocalic l and n, sometimes followed by the merger of the two surrounding vowels, or by the insertion of an epenthetic vowel between them: cf. Lat. salire ("to leave"), tenere ("to have"), catenam ("chain"), Sp. salir, tener, cadena, Port. sair, ter, cadeia.

When the elided consonant was n, it often nasalized the preceding vowel: cf. Lat. manum ("hand"), ranam ("frog"), bonum ("good"), Port. mão, rãa, bõo (now mão, rã, bom). This process was the source of most of the language's distinctive nasal diphthongs. In particular, the Latin endings -anem, -anum and -onem became -ão in most cases, cf. Lat. canem ("dog"), germanum ("brother"), rationem ("reason") with Modern Port. cão, irmão, razão, and their plurals -anes, -anos, -ones normally became -ães, -ãos, -ões, cf. cães, irmãos, razões.

The Portuguese language is also the only Romance language that developed the clitic case mesoclisis: cf. dar-te-ei (I'll give thee), amar-te-ei (I'll love you), contactá-los-ei (I'll contact them). And it was also the only Romance language to develop the "syntactic pluperfect past tense": cf. eu estivera (I had been), eu vivera (I had lived), vós vivêreis (you had lived). It also has single three other tense cases among the Romance languages.

Vocabulary

Most of the lexicon of Portuguese is derived from Latin. Nevertheless, because of the Moorish occupation of the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages, and the participation of Portugal in the Age of Discovery, it has adopted loanwords from all over the world.

Very few Portuguese words can be traced to the pre-Roman inhabitants of Portugal, which included the Gallaeci, Lusitanians, Celtici and Cynetes. The Phoenicians and Carthaginians, briefly present, also left some scarce traces. Some notable examples are abóbora "pumpkin" and bezerro "year-old calf", from the nearby Celtiberian language (probably through the Celtici); cerveja "beer", from Celtic; through Latin "cervisia."

In the 5th century, the Iberian Peninsula (the Roman Hispania) was conquered by the Germanic Suebi and Visigoths. As they adopted the Roman civilization and language, however, these people contributed only a few words to the lexicon, mostly related to warfare—such as espora "spur", estaca "stake", and guerra "war", from Gothic *spaúra, *stakka, and *wirro, respectively. The influence also exists in toponymic surnames and patronymic surnames borne by Visigoth sovereigns and their descendants, and it dwells on placenames such has Ermesinde, Esposende and Resende where sinde and sende are derived from the Germanic "sinths" (military expedition) and in the case of Resende, the prefix re comes from Germanic "reths" (council).

Between the 9th and 13th centuries, Portuguese acquired about 900 words from Arabic by influence of Moorish Iberia. They are often recognizable by the initial Arabic article a(l)-, and include many common words such as aldeia "village" from الضيعة alḍai`a (or from Edictum Rothari: aldii, aldias),[80] alface "lettuce" from الخس alkhass, armazém "warehouse" from المخزن almakhzan, and azeite "olive oil" from الزيت azzait. From Arabic came also the grammatically peculiar word oxalá إن شاء الله "hopefully". The Mozambican currency name metical was derived from the word متقال mitqāl, a unit of weight. The word Mozambique itself is from the Arabic name of sultan Muça Alebique (Musa Alibiki).

Starting in the 15th century, the Portuguese maritime explorations led to the introduction of many loanwords from Asian languages. For instance, catana "cutlass" from Japanese katana and chá "tea" from Chinese chá.

From South America came batata "potato", from Taino; ananás and abacaxi, from Tupi–Guarani naná and Tupi ibá cati, respectively (two species of pineapple), and tucano "toucan" from Guarani tucan.

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, because of the role of Portugal as intermediary in the Atlantic slave trade, and the establishment of large Portuguese colonies in Angola, Mozambique, and Brazil, Portuguese acquired several words of African and Amerind origin, especially names for most of the animals and plants found in those territories. While those terms are mostly used in the former colonies, many became current in European Portuguese as well. From Kimbundu, for example, came kifumate > cafuné "head caress" (Brazil), kusula > caçula "youngest child" (Brazil), marimbondo "tropical wasp" (Brazil), and kubungula > bungular "to dance like a wizard" (Angola).

Finally, it has received a steady influx of loanwords from other European languages. For example, melena "hair lock", fiambre "wet-cured ham" (in Portugal, in contrast with presunto "dry-cured ham" from Latin prae-exsuctus "dehydrated"; not in Brazil), and castelhano "Castilian", from Spanish; colchete/crochê "bracket"/"crochet", paletó "jacket", batom "lipstick", and filé/filete "steak"/"slice", rua "street" respectively, from French crochet, paletot, bâton, filet; macarrão "pasta", piloto "pilot", carroça "carriage", and barraca "barrack", from Italian maccherone, pilota, carrozza, baracca; and bife "steak", futebol, revólver, estoque, folclore, from English beef, football, revolver, stock, folklore.

Before the last four decades, Brazilians adopted a greater number of loanwords from Japanese and other European languages (due to the historical immigration affecting their demographics), and they were and are also more willing to adopt foreign terms that come from globalisation than the Portuguese, while the degree of African, Tupian and other Amerindian lexicon in Brazilian Portuguese is showed to be surprisingly lesser than that commonly expected of the said variant by the local Africanist and Indianist academia (that also has to some degree influenced the common sense of what gives a different cultural identity of Brazilians in relation to the Portuguese), so that its lexicon is almost identical (about 99%) to that of European Portuguese.[81][82][83]

Many Brazilian Portuguese colonial settlers were from northern and insular Portugal[84] apart from some historically important illegal immigrants from elsewhere in Europe, such as Galicia, France and the Netherlands.[85] It should be noted that Brazil received more European immigrants in its colonial history than the United States. Between 1500 and 1760, 700.000 Europeans settled in Brazil, while 530.000 Europeans settled in the United States for the same given time.[86]

Classification and related languages

Portuguese belongs to the West Iberian branch of the Romance languages, and it has special ties with the following members of this group:

- Galician, Fala and portunhol da pampa (the way riverense and its sibling dialects are referred to in Portuguese), its closest relatives.

- Mirandese, Leonese, Asturian, Extremaduran and Cantabrian (Astur-Leonese languages). Mirandese is the only recognised regional language spoken in Portugal (beside Portuguese, the only official language in Portugal).

Despite the obvious lexical and grammatical similarities between Portuguese and other Romance languages i.e., French, Italian, it is not mutually intelligible with them, except for Galician-Portuguese descendants, Mirandese, and Spanish. Portuguese speakers will usually need some formal study of basic grammar and vocabulary before attaining a reasonable level of comprehension in the other Romance languages, and vice versa.

Portuguese has a larger phonemic inventory than Spanish, and its dialect-varying system of allophony furthers distance even more. That could explain why it is only moderately intelligible to Spanish speakers despite the strong lexical similarity between the two languages; Portuguese speakers on the other hand have quite a high degree of comprehension of Spanish.

Communication is quite good between monolingual Brazilians and Spanish-speaking Latin Americans; between monolingual Portuguese and Spanish-speaking Spaniards the accents can make things more challenging. However, educated Portuguese and Spaniards can usually understand one another quite well. And portunhol, a form of code-switching, has far more users in the Americas (not to be confused with the portunhol spoken in the borders of Brazil with Uruguay and Paraguay, that is a Portuguese dialect heavily influenced by Spanish rather than code-switching).

Galician-Portuguese in Spain

The closest language to Portuguese is Galician, spoken in the autonomous community of Galicia (northwestern Spain). The two were at one time a single language, known today as Galician-Portuguese, but since the political separation of Portugal from Galicia they have diverged, especially in pronunciation and vocabulary. But there is still a linguistic continuity, the variant of Galician referred to as "galego-português baixo-limiao" spoken in several Galician villages between the municipalities of Entrimo and Lobios and the transborder region of the natural park of Peneda-Gerês/Xurês. "Considered a rarity, a living vestige of the medieval language that ranged from Cantabria to Mondego[...]".[87] As reported by UNESCO, due to the pressure of the Spanish language in the standard official version of the Galician language, the Galician language was in the verge of disappearing.[87] According to Unesco´s philologist Tapani Salminen, the proximity with the Portuguese language makes Galician a special language that is protected due to its proximity to the Portuguese language.[88] Nevertheless, the core vocabulary and grammar of Galician are still noticeably closer to Portuguese than to those of Spanish. In particular, like Portuguese, it uses the future subjunctive, the personal infinitive, and the synthetic pluperfect. Mutual intelligibility (estimated at 85% by R. A. Hall, Jr., 1989)[89] is very good between Galicians and northern Portuguese, but less so between Galicians and Brazilians. Nevertheless, many linguists still consider Galician to be a co-dialect of the Portuguese language. The government of Galicia has passed a law making the Portuguese language mandatory at all the school levels, intended to encourage the use of Portuguese at all levels of Galician society. Galicia will also become a full member of the CPLP (countries in the world that speak Portuguese).

Another member of the Galician-Portuguese group, most commonly thought of as a Galician dialect, is spoken in the Eonavian region in a western strip in Asturias and the westernmost parts of the provinces of León and Zamora, along the frontier with Galicia, between the Eo and Navia rivers (or more exactly Eo and Frexulfe rivers). It is called eonaviego or gallego-asturiano by its speakers.

The Fala language, known by its speakers as xalimés, mañegu, a fala de Xálima and chapurráu and in Portuguese as a fala de Xálima, a fala da Estremadura, o galego da Estremadura, valego ou galaico-estremenho, is another descendant of Galician-Portuguese, spoken by a small number of people in the Spanish towns of Valverde del Fresno (Valverdi du Fresnu), Eljas (As Ellas) and San Martín de Trevejo (Sa Martín de Trevellu) in the autonomous community of Extremadura, near the border with Portugal.

There is a number of other places in Spain in which the native language of the common people is a descendant of the Galician-Portuguese group, such as La Alamedilla, Cedillo (Cedilho), Herrera de Alcántara (Ferreira de Alcântara) and Olivenza (Olivença), but in these municipalities, what is spoken is actually Portuguese, not disputed as such in the mainstream.

It should be noticed that the diversity of dialects of the Portuguese language is known since the time of medieval Portuguese-Galician language when it coexisted with the Lusitanian-Mozarabic dialect, spoken in the south of Portugal. The dialectal diversity becomes more evident in the work of Fernão de Oliveira, in the Grammatica da Lingoagem Portuguesa, (1536), where he remarks that the people of Portuguese regions of Beira, Alentejo, Estremadura, and Entre Douro e Minho, all speak differently from each other. Also Contador de Argote (1725) distinguishes three main varieties of dialects: the local dialects, the dialects of time, and of profession (work jargon). Of local dialects he highlights five main dialects: the dialect of Estremadura, of Entre Douro e Minho, of Beyra, of Algarve and of Trás os Montes. He also makes reference to the overseas dialects, the rustic dialects, the poetic dialect and that of prose.[90]

In the kingdom of Portugal Ladinho or Lingoagem Ladinha was the name given to the pure Portuguese language romance, without any mixture of Aravia or Gerigonça Judenga.[91] While the term "língua vulgar" was used to name the language before D. Dinis decided to call it Portuguese language,[92] thus the erudit version used and known as Galician-Portuguese, the language of the Portuguese court, all other Portuguese dialects were spoken at the same time. In a historical perspective the Portuguese language was never just one dialect. Just like today there is a standard Portuguese (actually two) among the several dialects of Portuguese, in the past there was Galician-Portuguese as the "standard" while it coexisted among other dialects.

Influence on other languages

Portuguese has provided loanwords to many languages, such as Indonesian, Manado Malay, Malayalam, Sri Lankan Tamil and Sinhalese, Malay, Bengali, English, Hindi, Swahili, Afrikaans, Konkani, Marathi, Tetum, Xitsonga, Papiamentu, Japanese, Lanc-Patuá (spoken in northern Brazil), Esan and Sranan Tongo (spoken in Suriname). It left a strong influence on the língua brasílica, a Tupi–Guarani language, which was the most widely spoken in Brazil until the 18th century, and on the language spoken around Sikka in Flores Island, Indonesia. In nearby Larantuka, Portuguese is used for prayers in Holy Week rituals. The Japanese–Portuguese dictionary Nippo Jisho (1603) was the first dictionary of Japanese in a European language, a product of Jesuit missionary activity in Japan. Building on the work of earlier Portuguese missionaries, the Dictionarium Anamiticum, Lusitanum et Latinum (Annamite–Portuguese–Latin dictionary) of Alexandre de Rhodes (1651) introduced the modern orthography of Vietnamese, which is based on the orthography of 17th-century Portuguese. The Romanization of Chinese was also influenced by the Portuguese language (among others), particularly regarding Chinese surnames; one example is Mei. During 1583–88 Italian Jesuits Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci created a Portuguese–Chinese dictionary—the first ever European–Chinese dictionary.[93][94]

Derived languages

Beginning in the 16th century, the extensive contacts between Portuguese travelers and settlers, African and Asian slaves, and local populations led to the appearance of many pidgins with varying amounts of Portuguese influence. As each of these pidgins became the mother tongue of succeeding generations, they evolved into fully fledged creole languages, which remained in use in many parts of Asia, Africa and South America until the 18th century. Some Portuguese-based or Portuguese-influenced creoles are still spoken today, by over 3 million people worldwide, especially people of partial Portuguese ancestry.

Phonology

Portuguese phonology is similar to those of languages such as Catalan, French (especially that of Quebec), the Celto-Italic languages, Occitan and Franco-Provençal, unlike that of Spanish, similar to those of Sardinian and Southern Italian dialects.

There is a maximum of 9 oral vowels and 19 consonants, though some varieties of the language have fewer phonemes (Brazilian Portuguese is usually analyzed as having 8 oral vowels). There are also five nasal vowels, which some linguists regard as allophones of the oral vowels, ten oral diphthongs, and five nasal diphthongs. In total, Brazilian Portuguese has 13 vowel phonemes.[95][96]

Vowels

To the seven vowels of Vulgar Latin, European Portuguese has added two near central vowels, one of which tends to be elided in rapid speech, like the e caduc of French ([ɯ̽], but commonly represented as /ɨ/). The functional load of these two additional vowels is very low. The high vowels /e o/ and the low vowels /ɛ ɔ/ are four distinct phonemes, and they alternate in various forms of apophony.

Like Catalan, Portuguese uses vowel quality to contrast stressed syllables with unstressed syllables: isolated vowels tend to be raised, and in some cases centralized, when unstressed. Brazilian Portuguese, nevertheless, tends to contrast vowel height of unstressed vowels in different ways in relation to other national variants, so more vowel allophones may arise, while [a] and [ɐ] occur in a complementary distribution to which dialects disagree. Nasal diphthongs occur mostly at the ends of words and have [ɪ̯̃] and [ʊ̯̃] as non-syllabic elements in the Brazilian dialects where [ɪ] and [ʊ] are present.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ĩ | u ũ | |

| Near-close | (ɪ ~ ɪ̃) | (ɯ̟) (ʊ ~ ʊ̃) | |

| Close-mid | e | o | |

| Mid | ẽ i.e. ẽ̞ (e̞) | ə ~ ɐ ə̃ ~ ɐ̃ |

õ i.e. õ̞ (o̞) |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | a | ||

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Guttural | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | ʁ | |||||

| Liquid | l | ɾ | ʎ | |||||||||

The consonant inventory of Portuguese is fairly conservative. The medieval affricates /ts/, /dz/, /tʃ/, /dʒ/ merged with the fricatives /s/, /z/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/, respectively, but not with each other, and there have been no other significant changes to the consonant phonemes since then. However, some notable dialectal variants and allophones have appeared, among which:

- All post-alveolars are prevalently alveolo-palatal at least in the fluminense and paulistano dialects,[58] with just a few variation for the sibilants and affricates, and are likely to have the said pronunciation elsewhere in Brazil, except for speakers of the nordestino and baiano dialects, as well sibilants and affricates in sulista and gaúcho speech. In Portugal and elsewhere in the Portuguese-speaking world, /ɲ/ and /ʎ/ are also alveolo-palatal, but the sibilants vary in allophony (they tend to be alveolo-palatal as coda, as in Rio de Janeiro, but palato-alveolar elsewhere).

- In most regions of Brazil and some rural Portuguese accents, /t/ and /d/ have the affricate allophones [tʃ ~ tɕ] and [dʒ ~ dʑ], respectively, before /i/, /ĩ/, and in some dialects, /ui/ and [ɪ ~ ɪ̃].

- At the end of a syllable, the phoneme /l/ is velarized to [ɫ] in most of European Portuguese and vocalized to [u̯] or [ʊ̯] in most of Brazilian Portuguese, though for both of these variants a few isolated dialects present the characteristics of the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, while conservative caipira speech have [ɻ] as allophone of coda /l/ instead. It is also slightly velarized before unrounded close and rounded back vowels in most dialects everywhere (except Northeastern Brazil), and can be slightly velarized in all positions in Portugal, Africa and in some parts of Brazil as the state of Rio de Janeiro. It turns into [ʎ] before [j] in Brazil.

- In all of Brazil and parts of Africa, /ɲ/ is pronounced as a nasal palatal approximant [j̃] between vowels, which nasalizes the preceding vowel, so that, for instance, ninho /ˈniɲu/ (nest) is pronounced IPA: [ˈnĩj̃u]. There is evidence that it may be the language's original sound.[99] Actual alveolo-palatal occlusive pronunciation in the said dialects is present in clusters of /n/ and [j], and may also be used to indicate emphasis. On the other hand, sometimes the nasal vowels are interpreted as appending a velar nasal /ŋ/ onto the end, as with bem, /bẽŋ/ (cf. Kristang).

- In African and Asian Portuguese, most of Portugal, and few parts of Brazil (e.g. Rio de Janeiro state and metropolitan Florianópolis), sibilants, if outside consonant clusters (e.g. fax IPA: [faks]), are always postalveolar at the ends of syllables, [ʃ ~ ɕ] before voiceless consonants, and [ʒ ~ ʑ] before voiced consonants (in Judaeo-Spanish, coda /s/ is often postalveolar too). The use of postalveolars is present but inconsistent in most of Northern and Northeastern Brazil e.g. estrelas "stars" IPA: [iʃˈtɾelɐs], but for the majority of Brazilian speakers and very few northern dialects of Portugal, only the alveolar sibilants /s/ and /z/ (apico-alveolars in Portugal) will occur in complementary distribution at the ends of syllables, depending on whether the consonant that follows is voiceless or voiced, as in English. Even speakers of dialects which use alveolar-only codas may not follow it consistently, especially in frontier regions and bigger cities where there is influence from more prestigious variants.

- In rural caipira speech, /ʎ/ is nearly always replaced with /j/, as such mulher (woman) becomes "muié", família (family) becomes "famíia", os olhos (the eyes) becomes "os oio" (but not óleos, oils, which is homophone with olhos in most of Brazil, and always pronounced with a lateral) and there goes, but it is also present in the colloquial speech of a number of sociolects, including some carioca and paulistano speech. Some Galician speakers also present this feature as an influence from yeísmo, a centuries-old phenomenon of Spanish in which /ʎ/ merges with /ʝ/ (the latter phoneme is absent in all Portuguese and Galician dialects), although it is discouraged by the Real Academia Galega.

- Although there are two rhotic phonemes, they contrast only between vowels. Word-initially and after /n l s/ only /ʁ/ occurs; after other consonants only /ɾ/ occurs. When a word ends in a rhotic and the other starts in a vowel, the phoneme used in the liaison-like sandhi is /ɾ/. No contrast occurs at the end of a syllable, but the actual sound in this position varies greatly depending on the dialect, especially in Brazil. Conservative setubalense dialect of Central Portugal uses /ʁ/ for all instances of the rhotic because of French phonological influences, though this is almost never true for younger generations and areas settled by migrants from elsewhere in Portugal.

- There is also considerable dialectal variation in the actual pronunciation of the rhotic phoneme /ʁ/. The actual uvular pronunciation [χ ʁ ʀ] is common in Portugal, although the older trill [r] is also heard. In Brazil, the total inventory of /ʁ/ allophones is rather long, or up to [r ç x ɣ χ ʁ ʀ ħ h ɦ], the latter eight, specially unvoiced [χ x h], being particularly common, while none of them except archaic [r], that contrast with the flap in all positions, are usual to occur alone in a given dialect. In many Brazilian dialects, /ʁ/ occurs before other consonants (much as /ʀ/ in Judaeo-Spanish), although in other dialects the sound of [ɾ] (as in Portugal, also used by many Brazilian speakers such as most cariocas to indicate emphasis e.g. sem vergonha "shameless, profligate, barefaced" IPA: [ˈsẽj̃ ve̞ɾˈɡõː.ɲɐ]), or even rarer sounds such as [ɹ], [ɻ] or [ɻ̝̊] can be used instead. Word-finally in Brazil, the rhotic is often dropped entirely when speaking colloquially; when preserved, the same variation occurs as before a consonant.

- The voiced stops [b d ɡ] are pronounced as the corresponding voiced fricatives [β ð ɣ] between vowels, or between vowels and the tap /ɾ/. Voiced fricatives are a much more common feature in Lisbon and surrounding areas than outside Portugal or among rural and older speakers of southern and insular Portugal at the other end. It is also more common in unstressed syllables.

Examples of different pronunciation

- Excerpt from the Portuguese national epic Os Lusíadas, by author Luís de Camões (I, 33)

| Original | IPA (Lisbon) | IPA (Rio de Janeiro) | IPA (São Paulo) | IPA (Santiago de Compostela) | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustentava contra ele Vénus bela, | suɕtẽˈtavə ˈkõtɾə ˈeɫɨ ˈvɛnuʑ ˈβɛɫə | suɕtẽ̞ˈtavə ˈkõtɾə ˈeɫi ˈvẽnuʑ ˈbɛɫə | sustẽ̞ˈtavə ˈkõtɾɐ ˈeɫɪ ˈvẽnuz ˈbɛlɐ | sustenˈtaβa ˈkontɾa ˈel ˈβɛnuz ˈβɛla | Held against him the beautiful Venus |

| Afeiçoada à gente Lusitana, | əfəjˈswaðaː ˈʒẽtɨ̥ ɫuziˈtɐnə | əfejsuˈaðaː ˈʑẽtɕi̥ ɫuziˈtɜ̃nə | ɐfeɪ̯sʊˈadaː ˈʑẽtɕɪ̥ ɫuziˈtənə | afejθoˈaðaː ˈʃente lusiˈtana | So fond of the Lusitanian people, |

| Por quantas qualidades via nela | puɾ ˈkwɐ̃təɕ kwəɫiˈðaðɨʑ ˈviə ˈnɛɫə | puʀ ˈkwɜ̃təɕ kwəɫiˈdadʑiʑ ˈviə ˈnɛɫə | pʊɾ ˈkwɜ̃təs kwɐɫiˈdadʑɪz ˈviɐ ˈnɛlə | poɾ ˈkantas kwaliˈðaðez ˈβia ˈnɛla | For the many qualities he saw in her |

| Da antiga tão amada sua Romana; | də̃ˈtiɣə ˈtɐ̃w̃ əˈmaðə ˈsuə ʁuˈmɐnə | dɐˀɜ̃ˈtɕiɣə tɜ̃w̃ ɐ̃ˈmaðə ˈsuə ʁo̞ˈmɜ̃nə | dɐ̃ːˈtɕiɣɐ ˈtɐ̃ʊ̯̃ ɐ̃ˈmadɐ ˈsuɐ ɦõ̞ˈmənə | danˈtiɣa ˈtaŋ aˈmaða ˈsua roˈmana | that reminded her of his dear old Rome; |

| Nos fortes corações, na grande estrela, |

nuɕ ˈfɔɾtɨ̥ɕ kuɾəˈsõj̃ɕ nə ˈɣɾɐ̃dɨ̥ɕˈtɾeɫə |

nuɕ ˈfɔxtɕi̥ɕ ko̞ɾɐˈsõj̃ɕ nə ˈɡɾɜ̃dʑi̥ɕˈtɾeɫə |

nʊs ˈfɔɾtɕɪ̥s koɾɐˈsõɪ̯̃s nɐ ˈɡɾɜ̃dʑɪ̥sˈtɾelɐ |

nos ˈfɔɾtes koɾaˈθons na ˈɣɾandesˈtɾela |

In their stout hearts, in the great star |

| Que mostraram na terra Tingitana, | kɨ̥ muɕˈtɾaɾə̃w̃ nə ˈtɛʁə tĩʒiˈtɐnə | ki̥ mo̞ɕˈtɾaɾɜ̃w̃ nɐ ˈtɛʁə tɕĩʑiˈtɜ̃nə | kɪ̥ mʊsˈtɾaɾɜ̃ʊ̯̃ nɐ ˈtɛɦɐ tɕĩʑiˈtənə | ke mosˈtɾaɾaŋ na ˈtɛra tin̠ʃiˈtana | that they displayed in the land of Tangiers, |

| E na língua, na qual quando imagina, | i nə ˈɫĩɡwə nə ˈkwaɫ ˈkwɐ̃dwiməˈʒinə | i nɐ̞ ˈɫĩɡwə nɐ̞ ˈkwaw ˈkwɜ̃dwĩməˈʑĩnə | ɪ nɐ̞ ˈɫĩɡwə nɐ̞ ˈkwaʊ̯ kwə̃dwĩmɐˈʑinə | e na ˈliŋɡwa na ˈkal ˈkando jmaˈʃina | And the language, which if you think of it |

| Com pouca corrupção crê que é a Latina. | kõ ˈpokə kuʁupˈsɐ̃w̃ ˈkɾe kiˈɛ ə ɫəˈtinə | kũ ˈpowkɐ ko̞ʀupˈsɜ̃w̃ kɾe ˈkjɛ ə ɫəˈtɕĩnə | kʊ̃ ˈpoːkɐ ko̞ʁup(i)ˈsɜ̃ʊ̯̃ ˈkɾe ˈkjɛ ɐ lɐˈtɕĩnɐ | kom ˈpowka korupˈθoŋ ˈkɾe ˈke ˈɛ a laˈtina | a little corrupted, you believe it to be Latin.[100] |

Grammar

A notable aspect of the grammar of Portuguese is the verb. Morphologically, more verbal inflections from classical Latin have been preserved by Portuguese than by any other major Romance language. It has also some innovations not found in other Romance languages (except Galician and the Fala):

- The present perfect has an iterative sense unique to the Galician-Portuguese language group. It denotes an action or a series of actions that began in the past and are expected to keep repeating in the future. For instance, the sentence Tenho tentado falar com ela would be translated to "I have been trying to talk to her", not "I have tried to talk to her". On the other hand, the correct translation of the question "Have you heard the latest news?" is not *Tem ouvido a última notícia?, but Ouviu a última notícia?, since no repetition is implied.[101]

- Vernacular Portuguese still uses the future subjunctive mood, which developed from medieval West Iberian Romance and in present-day Spanish and Galician has almost entirely fallen into disuse. The future subjunctive appears in dependent clauses that denote a condition that must be fulfilled in the future so that the independent clause will occur. English normally employs the present tense under the same circumstances:

- Se eu for eleito presidente, mudarei a lei.

- If I am elected president, I will change the law.

- Quando fores mais velho, vais entender.

- When you grow older, you will understand.

- The personal infinitive: infinitives can inflect according to their subject in person and number, often showing who is expected to perform a certain action; cf. É melhor voltares "It is better [for you] to go back", É melhor voltarmos "It is better [for us] to go back." Perhaps for this reason, infinitive clauses replace subjunctive clauses more often in Portuguese than in other Romance languages.

Writing system

| Portugal and non-1990 Agreement countries | Brazil and 1990 Agreement countries | translation |

|---|---|---|

| direcção | direção | direction |

| óptimo | ótimo | best, excellent, optimal |

Portuguese is written with 26 letters of the Latin script, making use of five diacritics to denote stress, vowel height, contraction, nasalization, and other sound changes (acute accent, grave accent, circumflex accent, tilde, and cedilla). Accented characters and digraphs are not counted as separate letters for collation purposes.

Spelling reforms

See also

- Brazilian Portuguese

- Portuguese literature

- Portuguese poetry

- List of Portuguese language poets

- List of countries where Portuguese is an official language

- List of international organisations which have Portuguese as an official language

- Brazilian literature

- List of Brazilian poets

- Lusophone

- Anglophone pronunciation of foreign languages (Portuguese section)

- Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP)

- Instituto Camões

- International Portuguese Language Institute

- Museum of the Portuguese Language

- Portuñol

- Portuguese in the United States

References

- ↑ http://www.krysstal.com/spoken.html

- ↑ The Brazilian Portuguese pronunciation is IPA: [ˈlĩɡwɐ poɾtuˈgezɐ].

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Estados-membros da CPLP" (in Portuguese). 28 February 2011.

- ↑ Michael Swan, Bernard Smith (2001). "Portuguese Speakers". Learner English: a Teacher's Guide to Interference and Other Problems. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ CIA World Factbook

- ↑ Henry Edward Watts. Miguel de Cervantes: His Life & Works.

- ↑ Joseph T. Shipley (1946). Encyclopedia of Literature. Philosophical Library. p. 1188.

- ↑ Prem Poddar, Rajeev S. Patke, Lars Jensen (2008). "Introduction: The Myths and Realities of Portuguese (Post) Colonial Society". A historical companion to postcolonial literatures: continental Europe and its empires. Edinburgh University Press. p. 431. ISBN 07-4862-394-9.

- ↑ NOVAimagem.co.pt / Portugal em LInha (2006-03-08). "Museu da Língua Portuguesa aberto ao público no dia 20". Noticiaslusofonas.com. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ "Portuguese language in Brazil". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Special Eurobarometer 243 "Europeans and their Languages"". European Commission. 2006. p. 6. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ↑ 99.8% declared speaking Portuguese in the 1991 census

- ↑ Medeiros, Adelardo. Portuguese in Africa – Angola

- ↑ Angola: Language Situation (2005). Keith Brown, ed. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- ↑ Medeiros, Adelardo Portuguese in Africa – Moçambique

- ↑ Medeiros, Adelardo Portuguese in Africa – Guiné-Bissau

- ↑ 13,100 Portuguese nationals in 2010 according to Population par nationalité on the site of the "Département des Statistiques d'Andorre"

- ↑ 0.13% or 25,779 persons speak it at home in the 2006 census, see Spoken at Home (full classification list) by Sex&producttype=Census Tables&method=Place of Usual Residence&areacode=0 "Language Spoken at Home from the 2006 census". Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ↑ "Bermuda". World InfoZone. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ↑ "Population by mother tongue, by province and territory (2006 Census)". Statistics Canada.

- ↑ Gomes, Nancy (2001). "Os portugueses nas Américas: Venezuela, Canadá e EUA". Actualidade das migrações. Janus. Retrieved 13 May 2011

- ↑ 580,000 estimated to use it as their mother tongue in the 1999 census and 490,444 nationals in the 2007 census, see Répartition des étrangers par nationalité

- ↑ "Japão: imigrantes brasileiros popularizam língua portuguesa" (in Portuguese). 2008.

- ↑ "4.6% according to the 2001 census, see". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "www.namibian.com.na". www.namibian.com.na. 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ "Languages of Paraguay".

- ↑ "Languages of Macau".

- ↑ Between 300,000 and 600,000 according to Pina, António (2001). "Portugueses na África do Sul". Actualidade das migrações. Janus. Retrieved 13 May 2011

- ↑ Fibbi, Rosita (2010). Les Portugais en Suisse. Office fédéral des migrations. Retrieved 13 May 2011

- ↑ See "Languages of Venezuela". and Gomes, Nancy (2001). "Os portugueses nas Américas: Venezuela, Canadá e EUA". Actualidade das migrações. Janus. Retrieved 13 May 2011

- ↑ Carvalho, Ana Maria (2010). "Portuguese in the USA". In Potowski, Kim. Language Diversity in the USA. Cambridge University Press. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-521-74533-8

- ↑ "''The Portuguese Foundation, Inc.''". Pfict.org. 2011-05-01. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ "''Jornal Brasileiras & Brasileiros''". Jornalbb.com. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ An immigration phenomenon: Why Portuguese is the second language of Massachusetts from www.boston.com Fall 2007

- ↑ Hispanic Reading Room of the U.S. Library of Congress Web site, Twentieth-Century Arrivals from Portugal Settle in Newark, New Jersey,

- ↑ "Brazucas (Brazilians living in New York)". Nyu.edu. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ↑ Hispanic Reading Room of the U.S. Library of Congress Web site, Whaling, Fishing, and Industrial Employment in Southeastern New England

- ↑ "Portuguese Language in Goa". Colaco.net. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ↑ "The Portuguese Experience: The Case of Goa, Daman and Diu". Rjmacau.com. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ↑ Factoria Audiovisual S.R.L. (2010-07-20). "El portugués será el tercer idioma oficial de la República de Guinea Ecuatorial - Página Oficial del Gobierno de la República de Guinea Ecuatorial". Guineaecuatorialpress.com. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ "Decreto sobre el portugues como idioma oficial - Página Oficial del Gobierno de la República de Guinea Ecuatorial" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ Factoria Audiovisual S.R.L. (2010-07-25). "El Presidente Obiang asiste a la Cumbre de la CPLP - Página Oficial del Gobierno de la República de Guinea Ecuatorial". Guineaecuatorialpress.com. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ "Official languages of Mercosul as agreed in the ''Protocol of Ouro Preto''". Actrav.itcilo.org. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ "Official statute of the organization". Oei.es. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ Artículo 23 for the official languages

- ↑ General Assembly of the OAS, Amendments to the Rules of Procedure of the General Assembly, 5 June 2000

- ↑ Article 11, Protocol on Amendments to the Constitutive Act of the African Union

- ↑ "Languages in Europe – Official EU Languages". EUROPA web portal. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- ↑ "The World Factbook -- Field Listing - Population - CIA". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- ↑ "Uruguayan government makes Portuguese mandatory" (in Portuguese). 5 November 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ↑ "Portuguese will be mandatory in high school" (in Spanish). 21 January 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ↑ "Portuguese language will be option in the official Venezuelan teachings" (in Portuguese). 24 May 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ↑ "Zambia will adopt the Portuguese language in their Basic school" (in Portuguese). 26 May 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 "Congo will start to teach Portuguese in schools" (in Portuguese). 4 June 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "Portuguese language gaining popularity". Anglopress Edicões e Publicidade Lda. 5 May 2007. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ↑ Leach, Michael (2007). "talking Portuguese; China and East Timor". Arena Magazine. Retrieved 18 May 2011

- ↑ (Portuguese) The process of Norm change for the good pronunciation of the Portuguese language in chant and dramatics in Brazil during 1938, 1858 and 2007

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 (Portuguese) Carioca accent is the standard – The so-called "supremacy of the carioca speech", an issue of norm

- ↑ From Audio samples of the dialects of Portuguese at the Instituto Camões website.

- ↑ "Nheengatu and caipira dialect". Sosaci.org. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ (Portuguese) Acoustic-phonetic characteristics of the Brazilian Portuguese's retroflex /r/: data from respondents in Pato Branco, Paraná. Irineu da Silva Ferraz. Pages 19-21

- ↑ (Portuguese) Syllable coda /r/ in the "capital" of the paulista hinterland: sociolinguistic analisis. Cândida Mara Britto LEITE. Page 111 (page 2 in the attached PDF)

- ↑ (Portuguese) Callou, Dinah. Leite, Yonne. "Iniciação à Fonética e à Fonologia". Jorge Zahar Editora 2001, p. 24

- ↑ (Portuguese) To know a language is really about separating correct from awry? Language is a living organism that varies by context and goes far beyond a collection of rules and norms of how to speak and write Museu da Língua Portuguesa.

- ↑ (Portuguese) Linguistic prejudice and the surprising (academic and formal) unity of Brazilian Portuguese

- ↑ (Portuguese)

- ↑ (Portuguese)

- ↑ (Portuguese)

- ↑ (Portuguese)

- ↑ (Portuguese)

- ↑ (Portuguese)

- ↑ "Learn about Portuguese language". Sibila. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ Note: the speaker of this sound file is from Rio de Janeiro, and he is talking about his experience with nordestino and nortista accents.

- ↑ por Caipira Zé Do Mér dia 17 de maio de 2011, 6 Comentários. "O MEC, o "português errado" e a linguistica… | ImprenÇa". Imprenca.com. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ "Cartilha Do Mec Ensina Erro De Português". Saindo da Matrix. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ None (2011-05-26). "Livro do MEC ensina o português errado ou apenas valoriza as formas linguísticas? - Jornal de Beltrão" (in (Portuguese)). Jornaldebeltrao.com.br. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ "Sotaque branco". Meia Maratona Internacional CAIXA de Brasília accessdate=25 September 2012.

- ↑ "O Que É? Amazônia". Associação de Defesa do Meio Ambiente Araucária (AMAR). Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ "Fala NORTE". Fala UNASP - Centro Universitário Adventista de São Paulo. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Rothari -Edictus

- ↑ Say It in Portuguese, p. vii, R. Prista], Courier Dover Publications, 1979

- ↑ Portuguese for Dummies, p. 9, Karen Keller, 2006

- ↑ Learner English, p. 113, Michael Swan, Bernard Smith, Cambridge University Press, 2001

- ↑ Florentino, Manolo, and Machado, Cacilda. (Portuguese) Essay about Portuguese immigration and the patterns of miscegenation in Brazil in the 19th and 20rh centuries (PDF file)

- ↑ (Portuguese) Eduardo Fonseca, the Dutch Brazilians – Brazilians in the Netherlands

- ↑ Renato Pinto Venâncio, "Presença portuguesa: de colonizadores a imigrantes" i.e. Portuguese presence: from colonizers to immigrants, chap. 3 of Brasil: 500 anos de povoamento (IBGE). Relevant extract available here

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 A FALA GALEGO-PORTUGUESA DA BAIXA LIMIA E CASTRO LABOREIRO

- ↑ O galego deixa de ser unha das linguas "en perigo" para a Unesco

- ↑ "Ethnologue". Ethnologue. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ↑ Jerónimo Cantador de Argote e a Dialectologia Portuguesa (continuação)

- ↑ Diccionario da lingua portugueza: recopilado de todos os impressos ..., Volume 2

- ↑ D.Dinis: o Rei a Língua e o Reino

- ↑ Yves Camus, "Jesuits' Journeys in Chinese Studies"

- ↑ "Dicionário Português–Chinês : Pu Han ci dian: Portuguese–Chinese dictionary", by Michele Ruggieri, Matteo Ricci; edited by John W. Witek. Published 2001, Biblioteca Nacional. ISBN 97-2565-298-3. Partial preview available on Google Books

- ↑ Português brasileiro – Wikipédia, a enciclopédia livre (Portuguese)

- ↑ Handbook of the International Phonetic Association pg. 126–130; the reference applies to the entire section

- ↑ Cruz-Ferreira (1995:91)

- ↑ Barbosa & Albano (2004:228–229)

- ↑ Rosa Mattos e Silva, O Português arcaico – fonologia, Contexto, 1991, p.73.

- ↑ White, Landeg. (1997). The Lusiads—English translation. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 01-9280-151-1

- ↑ Squartini, Mario (1998) Verbal Periphrases in Romance—Aspect, Actionality, and Grammaticalization ISBN 31-1016-160-5

- História da Lingua Portuguesa Instituto Camões

- A Língua Portuguesa in Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil (...)

Literature

- Poesia e Prosa Medievais, by Maria Ema Tarracha Ferreira, Ulisseia 1998, 3rd ed., ISBN 978-9-72-568124-4.

- Bases Temáticas—Língua Portuguesa in Instituto Camões

- Portuguese Literature in The Catholic Encyclopedia

Phonology, orthography and grammar

- Barbosa, Plínio A.; Albano, Eleonora C. (2004). "Brazilian Portuguese". Journal of the International Phonetic Association 34 (2): 227–232. doi:10.1017/S0025100304001756

- Cruz-Ferreira, Madalena (1995). "European Portuguese". Journal of the International Phonetic Association 25 (2): 90–94. doi:10.1017/S0025100300005223

- Mateus, Maria Helena & d'Andrade, Ernesto (2000) The Phonology of Portuguese ISBN 01-9823-581-X (Excerpt available at Google Books)

- Bergström, Magnus & Reis, Neves Prontuário Ortográfico Editorial Notícias, 2004.

- A pronúncia do português europeu—European Portuguese Pronunciation

- Dialects of Portuguese at the Instituto Camões

- Audio samples of the dialects of Portugal

- Audio samples of the dialects from outside Europe

- Portuguese Grammar

Reference dictionaries

- Antônio Houaiss (2000), Dicionário Houaiss da Língua Portuguesa (228,500 entries).

- Aurélio Buarque de Holanda Ferreira, Novo Dicionário da Língua Portuguesa (1809pp)

- English–Portuguese–Chinese Dictionary (Freeware for Windows/Linux/Mac)

Linguistic studies

- Cook, Manuela. Portuguese Pronouns and Other Forms of Address, from the Past into the Future - Structural, Semantic and Pragmatic Reflections, Ellipsis, vol. 11, APSA, www.portuguese-apsa.com/ellipsis, 2013

- Cook, Manuela. Uma Teoria de Interpretação das Formas de Tratamento na Língua Portuguesa, Hispania, vol 80, nr 3, AATSP, 1997

- Cook, Manuela. On the Portuguese Forms of Address: From "Vossa Mercê" to "Você", Portuguese Studies Review 3.2, Durham: University of New Hampshire, 1995

- Lindley Cintra, Luís F. Nova Proposta de Classificação dos Dialectos Galego- Portugueses (PDF) Boletim de Filologia, Lisboa, Centro de Estudos Filológicos, 1971.

External links

| Portuguese edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Portuguese |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Portuguese language. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Portuguese_phrasebook. |

- Learn Portuguese BBC

- USA Foreign Service Institute Portuguese basic course

- (Portuguese) Society for the Portuguese Language (Sociedade da Língua Portuguesa)

- AULP—Associação das Universidades de Língua Portuguesa Portuguese Language Universities Association.

- ABL—Academia Brasileira de letras (em português)—(Brazilian Academy of Letters) (Portuguese)

| |||||||||||||||||