Poincaré duality

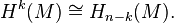

In mathematics, the Poincaré duality theorem, named after Henri Poincaré, is a basic result on the structure of the homology and cohomology groups of manifolds. It states that if M is an n-dimensional oriented closed manifold (compact and without boundary), then the kth cohomology group of M is isomorphic to the (n − k)th homology group of M, for all integers k

Poincaré duality holds for any coefficient ring, so long as one has taken an orientation with respect to that coefficient ring; in particular, since every manifold has a unique orientation mod 2, Poincaré duality holds mod 2 without any assumption of orientation.

History

A form of Poincaré duality was first stated, without proof, by Henri Poincaré in 1893. It was stated in terms of Betti numbers: The kth and (n − k) th Betti numbers of a closed (i.e. compact and without boundary) orientable n-manifold are equal. The cohomology concept was at that time about 40 years from being clarified. In his 1895 paper Analysis Situs, Poincaré tried to prove the theorem using topological intersection theory, which he had invented. Criticism of his work by Poul Heegaard led him to realize that his proof was seriously flawed. In the first two complements to Analysis Situs, Poincaré gave a new proof in terms of dual triangulations.

Poincaré duality did not take on its modern form until the advent of cohomology in the 1930s, when Eduard Čech and Hassler Whitney invented the cup and cap products and formulated Poincaré duality in these new terms.

Modern formulation

The modern statement of the Poincaré duality theorem is in terms of homology and cohomology: if M is a closed oriented n-manifold, and k is an integer, then there is a canonically defined isomorphism from the k-th cohomology group Hk(M) to the (n − k)th homology group Hn − k(M). (Here, homology and cohomology is taken with coefficients in the ring of integers, but the isomorphism holds for any coefficient ring.) Specifically, one maps an element of Hk(M) to its cap product with a fundamental class of M, which will exist for oriented M.

For non-compact oriented manifolds, one has to replace cohomology by cohomology with compact support.

Homology and cohomology groups are defined to be zero for negative degrees, so Poincaré duality in particular implies that the homology and cohomology groups of orientable closed n-manifolds are zero for degrees bigger than n.

Dual cell structures

Given a triangulated manifold, there is a corresponding dual polyhedral decomposition. The dual polyhedral decomposition is a cell decomposition of the manifold such that the k-cells of the dual polyhedral decomposition are in bijective correspondence with the (n−k)-cells of the triangulation, generalising the notion of dual polyhedra.

-- a picture of the parts of the dual-cells in a top-dimensional simplex.

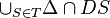

-- a picture of the parts of the dual-cells in a top-dimensional simplex.Precisely, let T be a triangulation of an n-manifold M. Let S be a simplex of T. We denote the dual cell (to be defined precisely) corresponding to S by DS. Let  be a top-dimensional simplex of T containing S. So we can think of S as a subset of the vertices of

be a top-dimensional simplex of T containing S. So we can think of S as a subset of the vertices of  . Then

. Then  is defined to be the convex hull (in

is defined to be the convex hull (in  ) of the barycentres of all subsets of the vertices of

) of the barycentres of all subsets of the vertices of  that contain

that contain  . One can check that if S is i-dimensional, then DS is an (n−i)-dimensional cell. Moreover, the dual cells to T form a CW-decomposition of M, and the only (n−i)-dimensional dual cell that intersects an i-cell S is DS. Thus the pairing

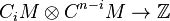

. One can check that if S is i-dimensional, then DS is an (n−i)-dimensional cell. Moreover, the dual cells to T form a CW-decomposition of M, and the only (n−i)-dimensional dual cell that intersects an i-cell S is DS. Thus the pairing  given by taking intersections induces an isomorphism

given by taking intersections induces an isomorphism  , where here

, where here  is the cellular homology of the triangulation T, and

is the cellular homology of the triangulation T, and  and

and  are the cellular homologies and cohomologies of the dual polyhedral/CW decomposition the manifold respectively. The fact that this is an isomorphism of chain complexes is a proof of Poincaré Duality. Roughly speaking, this amounts to the fact that the boundary relation for the triangulation T is the incidence relation for the dual polyhedral decomposition under the correspondence

are the cellular homologies and cohomologies of the dual polyhedral/CW decomposition the manifold respectively. The fact that this is an isomorphism of chain complexes is a proof of Poincaré Duality. Roughly speaking, this amounts to the fact that the boundary relation for the triangulation T is the incidence relation for the dual polyhedral decomposition under the correspondence  .

.

Naturality

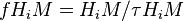

Note that Hk is a contravariant functor while Hn − k is covariant. The family of isomorphisms

- DM : Hk(M) → Hn − k(M)

is natural in the following sense: if

- f : M → N

is a continuous map between two oriented n-manifolds which is compatible with orientation, i.e. which maps the fundamental class of M to the fundamental class of N, then

- DN = f∗ DM f∗,

where f∗ and f∗ are the maps induced by f in homology and cohomology, respectively.

Note the very strong and crucial hypothesis that f maps the fundamental class of M to the fundamental class of N. Naturality does not hold for an arbitrary continuous map f, since in general f∗ is not an injection on cohomology. For example if f is a covering map then it maps the fundamental class of M to a multiple of the fundamental class of N. This multiple is the degree of the map f.

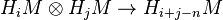

Bilinear pairings formulation

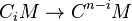

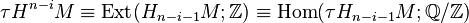

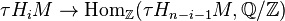

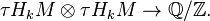

Assuming M is compact boundaryless and orientable, let

denote the torsion subgroup of  and let

and let

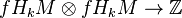

be the free part – all homology groups taken with integer coefficients in this section. Then there are bilinear maps which are duality pairings (explained below).

and

- (Here

is the quotient of the rationals by the integers, taken as an additive group.)

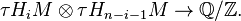

is the quotient of the rationals by the integers, taken as an additive group.) - (Notice that in the torsion linking form, there is a −1 in the dimension, so the paired dimensions add up to

rather than to

rather than to  )

)

The first form is typically called the intersection product and the 2nd the torsion linking form. Assuming the manifold M is smooth, the intersection product is computed by perturbing the homology classes to be transverse and computing their oriented intersection number. For the torsion linking form, one computes the pairing of x and y by realizing nx as the boundary of some class z. The form is the fraction with numerator the transverse intersection number of z with y and denominator n.

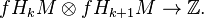

The statement that the pairings are duality pairings means that the adjoint maps

and

are isomorphisms of groups.

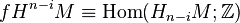

This result is an application of Poincaré Duality

together with the Universal coefficient theorem which gives an identification

and

.

.

Thus, Poincaré duality says that  and

and  are isomorphic, although there is no natural map giving the isomorphism, and similarly

are isomorphic, although there is no natural map giving the isomorphism, and similarly  and

and  are also isomorphic, though not naturally.

are also isomorphic, though not naturally.

- Middle dimension

While for most dimensions, Poincaré duality induces a bilinear pairing between different homology groups, in the middle dimension it induces a bilinear form on a single homology group. The resulting intersection form is a very important topological invariant.

What is meant by "middle dimension" depends on parity. For even dimension  which is more common, this is literally the middle dimension k, and there is a form on the free part of the middle homology:

which is more common, this is literally the middle dimension k, and there is a form on the free part of the middle homology:

By contrast, for odd dimension  which is less commonly discussed, it is most simply the lower middle dimension k, and there is a form on the torsion part of the homology in that dimension:

which is less commonly discussed, it is most simply the lower middle dimension k, and there is a form on the torsion part of the homology in that dimension:

However, there is also a pairing between the free part of the homology in the lower middle dimension k and in the upper middle dimension k+1:

The resulting groups, while not a single group with a bilinear form, are a simple chain complex and are studied in algebraic L-theory.

- Applications

This approach to Poincaré duality was used by Przytycki and Yasuhara to give an elementary homotopy and diffeomorphism classification of 3-dimensional lens spaces.[1]

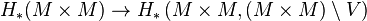

Thom Isomorphism Formulation

Poincaré Duality is closely related to the Thom Isomorphism Theorem, as we will explain here. For this exposition, let  be a compact, boundaryless oriented n-manifold. Let

be a compact, boundaryless oriented n-manifold. Let  be the product of

be the product of  with itself, let

with itself, let  be an open tubular neighbourhood of the diagonal in

be an open tubular neighbourhood of the diagonal in  . Consider the maps:

. Consider the maps:

-

inclusion.

inclusion.

-

-

excision map where

excision map where  is the normal disc bundle of the diagonal in

is the normal disc bundle of the diagonal in  .

.

-

-

the Thom Isomorphism. This map is well-defined as there is a standard identification

the Thom Isomorphism. This map is well-defined as there is a standard identification  which is an oriented bundle, so the Thom Isomorphism applies.

which is an oriented bundle, so the Thom Isomorphism applies.

-

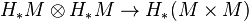

Combined, this gives a map  , which is the intersection product—strictly speaking it is a generalization of the intersection product above, but it is also called the intersection product. A similar argument with the Künneth theorem gives the torsion linking form.

, which is the intersection product—strictly speaking it is a generalization of the intersection product above, but it is also called the intersection product. A similar argument with the Künneth theorem gives the torsion linking form.

This formulation of Poincaré Duality has become quite popular[2] as it provides a means to define Poincaré Duality for any generalized homology theories provided one has a Thom Isomorphism for that homology theory. A Thom isomorphism theorem for a homology theory is now accepted as the generalized notion of orientability for a homology theory. For example, a  on a manifold turns out to be precisely what is needed to be orientable in the sense of complex topological k-theory.

on a manifold turns out to be precisely what is needed to be orientable in the sense of complex topological k-theory.

Generalizations and related results

The Poincaré-Lefschetz duality theorem is a generalisation for manifolds with boundary. In the non-orientable case, taking into account the sheaf of local orientations, one can give a statement that is independent of orientability: see Twisted Poincaré duality.

Blanchfield duality is a version of Poincaré duality which provides an isomorphism between the homology of an abelian covering space of a manifold and the corresponding cohomology with compact supports. It is used to get basic structural results about the Alexander module and can be used to define the signatures of a knot.

With the development of homology theory to include K-theory and other extraordinary theories from about 1955, it was realised that the homology H* could be replaced by other theories, once the products on manifolds were constructed; and there are now textbook treatments in generality. More specifically, there is a general Poincaré duality theorem for generalized homology theories which requires a notion of orientation with respect to a homology theory, and is formulated in terms of a generalized Thom Isomorphism Theorem. The Thom Isomorphism Theorem in this regard can be considered as the germinal idea for Poincaré duality for generalized homology theories.

Verdier duality is the appropriate generalization to (possibly singular) geometric objects, such as analytic spaces or schemes, while intersection homology was developed R. MacPherson and M. Goresky for stratified spaces, such as real or complex algebraic varieties, precisely so as to generalise Poincaré duality to such stratified spaces.

There are many other forms of geometric duality in algebraic topology, including Lefschetz duality, Alexander duality, Hodge duality, and S-duality.

More algebraically, one can abstract the notion of a Poincaré complex, which is an algebraic object that behaves like the singular chain complex of a manifold, notably satisfying Poincaré duality on its homology groups, with respect to a distinguished element (corresponding to the fundamental class). These are used in surgery theory to algebraicize questions about manifolds. A Poincaré space is one whose singular chain complex is a Poincaré complex. These are not all manifolds, but their failure to be manifolds can be measured by obstruction theory.

See also

References

Further reading

- Blanchfield, R. C. (1957), "Intersection theory of manifolds with operators with applications to knot theory", Annals of Mathematics 65 (2): 340–356, JSTOR 1969966

- Griffiths, Phillip; Harris, Joseph (1994), Principles of algebraic geometry, Wiley Classics Library, New York: Wiley, ISBN 978-0-471-05059-9, MR 1288523

External links

- Intersection form at the Manifold Atlas

- Linking form at the Manifold Atlas

the

the