Plasmon

| Condensed matter physics |

|---|

|

| Phases · Phase transition |

|

Solid · Liquid · Gas · Bose–Einstein condensate · Bose gas · Fermionic condensate · Fermi gas · Fermi liquid · Supersolid · Superfluidity · Luttinger liquid |

|

Phase phenomena |

|

Electronic phases Electronic band structure · Insulator · Mott insulator · Semiconductor · Semimetal · Conductor · Superconductor · Thermoelectric · Piezoelectric · Ferroelectric |

|

Electronic phenomena |

|

Magnetic phases |

In physics, a plasmon is a quantum of plasma oscillation. The plasmon is a quasiparticle resulting from the quantization of plasma oscillations just as photons and phonons are quantizations of electromagnetic and mechanical vibrations, respectively (although the photon is an elementary particle, not a quasiparticle). Thus, plasmons are collective oscillations of the free electron gas density, for example, at optical frequencies. Plasmons can couple with a photon to create another quasiparticle called a plasma polariton.

Since plasmons are the quantization of classical plasma oscillations, most of their properties can be derived directly from Maxwell's equations.

Explanation

Plasmons can be described in the classical picture as an oscillation of free electron density with respect to the fixed positive ions in a metal. To visualize a plasma oscillation, imagine a cube of metal placed in an external electric field pointing to the right. Electrons will move to the left side (uncovering positive ions on the right side) until they cancel the field inside the metal. If the electric field is removed, the electrons move to the right, repelled by each other and attracted to the positive ions left bare on the right side. They oscillate back and forth at the plasma frequency until the energy is lost in some kind of resistance or damping. Plasmons are a quantization of this kind of oscillation.

Role of plasmons

Plasmons play a large role in the optical properties of metals. Light of frequency below the plasma frequency is reflected, because the electrons in the metal screen the electric field of the light. Light of frequency above the plasma frequency is transmitted, because the electrons cannot respond fast enough to screen it. In most metals, the plasma frequency is in the ultraviolet, making them shiny (reflective) in the visible range. Some metals, such as copper[1] and gold,[2] have electronic interband transitions in the visible range, whereby specific light energies (colors) are absorbed, yielding their distinct color. In semiconductors, the valence electron plasma frequency is usually in the deep ultraviolet,[3][4] which is why they are reflective.

The plasmon energy can often be estimated in the free electron model as

where  is the conduction electron density,

is the conduction electron density,  is the elementary charge,

is the elementary charge,  is the electron mass,

is the electron mass,  the permittivity of free space,

the permittivity of free space,  the reduced Planck constant and

the reduced Planck constant and  the plasmon frequency.

the plasmon frequency.

Surface plasmons

Surface plasmons are those plasmons that are confined to surfaces and that interact strongly with light resulting in a polariton.[5] They occur at the interface of a vacuum and material with a small positive imaginary and large negative real dielectric constant (usually a metal or doped dielectric). They play a role in Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy and in explaining anomalies in diffraction from metal gratings (Wood's anomaly), among other things. Surface plasmon resonance is used by biochemists to study the mechanisms and kinetics of ligands binding to receptors (i.e. a substrate binding to an enzyme).

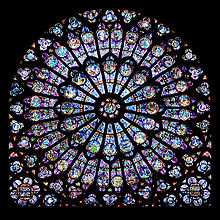

More recently surface plasmons have been used to control colors of materials.[6] This is possible since controlling the particle's shape and size determines the types of surface plasmons that can couple to it and propagate across it. This in turn controls the interaction of light with the surface. These effects are illustrated by the historic stained glass which adorn medieval cathedrals. In this case, the color is given by metal nanoparticles of a fixed size which interact with the optical field to give the glass its vibrant color. In modern science, these effects have been engineered for both visible light and microwave radiation. Much research goes on first in the microwave range because at this wavelength material surfaces can be produced mechanically as the patterns tend to be of the order a few centimeters. To produce optical range surface plasmon effects involves producing surfaces which have features <400 nm. This is much more difficult and has only recently become possible to do in any reliable or available way.

Possible applications

Position and intensity of plasmon absorption and emission peaks are affected by molecular adsorption, which can be used in molecular sensors. For example, a fully operational prototype device detecting casein in milk has been fabricated. The device is based on detecting a change in absorption of a gold layer.[7] Localized surface plasmons of metal nanoparticles can be used for sensing different types molecules, proteins, etc.

Plasmons are being considered as a means of transmitting information on computer chips, since plasmons can support much higher frequencies (into the 100 THz range, while conventional wires become very lossy in the tens of GHz). However, for plasmon-based electronics to be useful, the analog to the transistor, called a plasmonster, first needs to be created.[8]

Plasmons have also been proposed as a means of high-resolution lithography and microscopy due to their extremely small wavelengths. Both of these applications have seen successful demonstrations in the lab environment. Finally, surface plasmons have the unique capacity to confine light to very small dimensions which could enable many new applications.

Surface plasmons are very sensitive to the properties of the materials on which they propagate. This has led to their use to measure the thickness of monolayers on colloid films, such as screening and quantifying protein binding events. Companies such as Biacore have commercialized instruments which operate on these principles. Optical surface plasmons are being investigated with a view to improve makeup by L'Oréal among others.[9]

In 2009, a Korean research team found a way to greatly improve organic light-emitting diode efficiency with the use of plasmons.[10]

A group of European researchers led by IMEC has begun work to improve solar cell efficiencies and costs through incorporation of metallic nanostructures (using plasmonic effects) that can enhance absorption of light into different types of solar cells: crystalline silicon (c-Si), high-performance III-V, organic, and dye-sensitized solar cells. [11]

Full color holograms using plasmonics[12] have been demonstrated.

See also

References

- ↑ Burdick, Glenn (1963). "Energy Band Structure of Copper". Physical Review 129: 138. Bibcode:1963PhRv..129..138B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.129.138.

- ↑ S.Zeng et al. (2011). "A review on functionalized gold nanoparticles for biosensing applications". Plasmonics 6 (3): 491–506. doi:10.1007/s11468-011-9228-1.

- ↑ , have electronic interband transitions in the visible range, whereby specific light energies (colors) are absorbed, yielding their distinct color Kittel, C. (2005). Introduction to Solid State Physics (8th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 403, table 2.

- ↑ Böer, K. W. (2002). Survey of Semiconductor Physics 1 (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 525.

- ↑ S.Zeng et al. (2012). "Size dependence of Au NP-enhanced surface plasmon resonance based on differential phase measurement". Sensors and Actuators B. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2012.09.073.

- ↑ "LEDs work like butterflies' wings". BBC News. November 18, 2005. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ↑ Heip, H. M.; et al. (2007). "A localized surface plasmon resonance based immunosensor for the detection of casein in milk". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials 8 (4): 331. Bibcode:2007STAdM...8..331M. doi:10.1016/j.stam.2006.12.010.

- ↑ Lewotsky, Kristin (2007). "The Promise of Plasmonics". SPIE Professional. doi:10.1117/2.4200707.07.

- ↑ "The L'Oréal Art & Science of Color Prize – 7th Prize Winners".

- ↑ "Prof. Choi Unveils Method to Improve Emission Efficiency of OLED". KAIST. 9 July 2009.

- ↑ "EU partners eye metallic nanostructures for solar cells". ElectroIQ. 30 March 2010.

- ↑ Kawata, Satoshi. "New technique lights up the creation of holograms". Phys.org. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- Stefan Maier (2007). Plasmonics: Fundamentals and Applications. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-33150-8.

- Michael G. Cottam and David R. Tilley (1989). Introduction to Surface and Superlattice Excitations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-32154-9.

- Heinz Raether (1980). Excitation of plasmons and interband transitions by electrons. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-09677-9.

- Barnes, W. L.; Dereux, A.; Ebbesen T.W. (2003). "Surface plasmon subwavelength optics". Nature 424 (6950): 824–830. Bibcode:2003Natur.424..824B. doi:10.1038/nature01937. PMID 12917696.

- Zayats, A. V.; Smolyaninov, I. I.; Maradudin, A. A. (2005). "Nano-optics of surface plasmon polaritons". Physics Reports 408 (3–4): 131–314. Bibcode:2005PhR...408..131Z. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2004.11.001.

- Atwater, Harry A. (2007). "The Promise of Plasmonics". Scientific American 296 (4): 56–63. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0407-56. PMID 17479631.

- Ozbay, Ekmel (2006). "Plasmonics: Merging Photonics and Electronics at Nanoscale Dimensions". Science 311 (5758): 189–193. Bibcode:2006Sci...311..189O. doi:10.1126/science.1114849. PMID 16410515.

- Schuller, Jon; Barnard, Edward; Cai, Wenshan; Jun, Young Chul; White, Justin; Brongersma, Mark L. (2010). "Plasmonics for Extreme Light Concentration and Manipulation". Nature Materials 9 (3): 193–204. Bibcode:2010NatMa...9..193S. doi:10.1038/nmat2630. PMID 20168343.

- Brongersma, Mark; Shalaev, Vladimir (2010). "The case for plasmonics". Science 328: 440–441. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..440B. doi:10.1126/science.1186905.

External links

- A selection of free-download papers on Plasmonics in New Journal of Physics

- http://www.plasmonicfocus.com

- http://www.sprpages.nl

- http://www.qub.ac.uk/mp/con/plasmon/sp1.html

- http://www.nano-optics.org.uk

- Plasmonic computer chips move closer

- Progress at Stanford for use in computers

- Slashdot: A Plasmonic Revolution for Computer Chips?

- A Microscope from Flatland Physical Review Focus, January 24, 2005

- http://en.wikinews.org/wiki/Invisibility_shield_gets_blueprint

- http://www.plasmonanodevices.org

- http://www.eu-pleas.org

- http://www.plasmocom.org

- Test the limits of plasmonic technology

- http://www.activeplasmonics.org

- http://www.plaisir-project.eu

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||