Pituitary adenoma

| Pituitary adenoma | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| |

| ICD-10 | D35.2 |

| ICD-9 | 237.0 |

| ICD-O: | M8272/0 |

| MedlinePlus | 000704 |

| eMedicine | neuro/312 |

| MeSH | D010911 |

Pituitary adenomas are noncancerous tumors that occur in the pituitary gland. Pituitary adenomas are generally divided into three categories dependent upon their biological functioning: benign adenoma, invasive adenoma, or carcinomas, with carcinomas accounting for 0.1% to 0.2%, approximately 35% being invasive adenomas and most being benign adenomas. Pituitary adenomas represent from 10% to 25% of all intracranial neoplasms[citation needed] and the estimated prevalence rate in the general population is approximately 17%.[1]

Non-invasive and non-secreting pituitary adenomas are considered to be benign in the literal as well as the clinical sense; however a recent meta-analysis (Fernández-Balsells, et al. 2011) of available research has shown there are to date scant studies - of poor quality - to either support or refute this assumption.

Adenomas which exceed 10 millimetres (0.39 in) in size are defined as macroadenomas, with those smaller than 10 mm referred to as microadenomas. Most pituitary adenomas are microadenomas, and have an estimated prevalence of 16.7% (14.4% in autopsy studies and 22.5% in radiologic studies).[1][2] A majority of pituitary microadenomas often remain undiagnosed and those that are diagnosed are often found as an incidental finding, and are referred to as incidentalomas.

Pituitary macroadenomas are the most common cause of hypopituitarism, and in the majority of cases they are non-secreting adenomas[3].

Invasive adenomas may invade the dura mater, cranial bone, or sphenoid bone. Although previously believed that clinically active pituitary adenomas were rare, recent studies have suggested that they may affect approximately one in 1000 of the general population.[4]

Overview

The pituitary gland or hypophysis is often referred to as the "master gland" of the human body. Part of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, it controls most of the body's endocrine functions via the secretion of various hormones into the circulatory system. The pituitary gland is located below the brain in a depression (fossa) of the sphenoid bone known as the sella turcica. Although anatomically and functionally connected to the brain, the pituitary gland[5] and sits outside the blood–brain barrier. It is separated from the subarachnoid space by the diaphragma sella, therefore the arachnoid mater and thus cerebral spinal fluid cannot enter the sella turcica.

The pituitary gland is divided into two lobes, the anterior lobe (which accounts for two thirds of the volume of the gland), and the posterior lobe (one third of the volume) separated by the pars intermedia.

The posterior lobe (the neural lobe or neurohypophysis) of the pituitary gland is not, despite its name, a true gland. The posterior lobe contains axons of neurons that extend from the hypothalamus to which it is connected via the pituitary stalk. The hormones vasopressin and oxytocin, produced by the neurons of the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus, are stored in the posterior lobe and released from axon endings (dendrites) within the lobe.[6]

The pituitary gland's anterior lobe (adenohypophysis) is a true gland which produces and secretes six different hormones: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), growth hormone (GH), and prolactin (PRL).[7]

Classification

Pituitary adenomas are classified based on upon anatomical, histological and functional criteria.[8]

- Anatomically pituitary tumors are classified by their size based on radiological findings; either microadenomas (less than <10 mm) or macroadenomas (equal or greater than ≥I0 mm).

- Classification based on radioanatomical findings places adenomas into 1 of 4 grades (I–IV):[9]

- Stage I: microadenomas (<1 cm) without sella expansion.

- Stage II: macroadenomas (≥1 cm) and may extend above the sella.

- Stage III: macroadenomas with enlargement and invasion of the floor or suprasellar extension.

- Stage IV is destruction of the sella.

- Histological classification utilizes an immunohistological characterization of the tumors in terms of their hormone production.[8] Historically they were classed as either basophilic, acidophilic, or chromophobic on the basis of whether or not they took up the tinctorial stains hematoxylin and eosin. This classification has fallen into disuse, in favor of a classification based on what type of hormone is secreted by the tumor. Approximately 20-25% of adenomas do not secrete any readily identifiable active hormones ('non-functioning tumors') yet they are still sometimes referred to as 'chromophobic'.

- Functional classification is based upon the tumors endocrine activity as determined by serum hormone levels and pituitary tissue cellular hormone secretion detected via immunohistochemical staining.[10] The "Percentage of hormone production cases" values are the fractions of adenomas producing each related hormone of each tumor type as compared to all cases of pituitary tumors, and does not directly correlate to the percentages of each tumor type because of smaller or greater incidences of absence of secretion of the expected hormone. Thus, nonsecretive adenomas may be either null cell adenomas or a more specific adenoma that, however, remains nonsecretive.

| Type of adenoma | Secretion | Staining | Pathology | Percentage of hormone production cases |

| lactotrophic adenomas (prolactinomas) | secrete prolactin | acidophilic | galactorrhea, hypogonadism, amenorrhea, infertility, and impotence | 30%[11] |

| somatotrophic adenomas | secrete growth hormone (GH) | acidophilic | acromegaly in adults; gigantism in children | 15%[11] |

| corticotrophic adenomas | secrete adenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) | basophilic | Cushing's disease | |

| gonadotrophic adenomas | secrete luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and their subunits | basophilic | usually doesn't cause symptoms | 10%[11] |

| thyrotrophic adenomas (rare) | secrete thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | basophilic to chromophobic | occasionally hyperthyroidism,[12] usually doesn't cause symptoms | Less than 1%[11] |

| null cell adenomas | do not secrete hormones | may stain positive for synaptophysin | 25% of pituitary adenomas are nonsecretive[11] |

Pituitary incidentalomas

Pituitary incidentalomas are pituitary tumors that are characterized as an incidental finding. They are often discovered by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed in the evaluation of unrelated medical conditions such as suspected head trauma, in cancer staging or in the evaluation of nonspecific symptoms such as dizziness and headache. It is not uncommon for them to be discovered at autopsy. In a meta-analysis, adenomas were found in an average of 16.7% in postmortem studies, with most being microadenomas (<10mm); macrodenomas accounted for only 0.16% to 0.2% of the decedents.[1] While non-secreting, noninvasive pituitary microadenomas are generally considered to be literally as well as clinically benign, there are to date scant studies of low quality to support this assertion.[13] The presence of a microadenoma has been positively identified as a risk factor for suicide in a postmortem study of suicide victims.[14][15]

It has been recommended in the current Clinical Practice Guidelines (2011) by the Endocrine Society - a professional, international medical organization in the field of endocrinology and metabolism - that all patients with pituitary incidentalomas undergo a complete medical history and physical examination, laboratory evaluations to screen for hormone hypersecretion and for hypopituitarism. If the lesion is in close proximity to the optic nerves or optic chiasm, a visual field examination should be performed. For those with incidentalomas which do not require surgical removal, follow up clinical assessments and neuroimaging should be performed as well follow-up visual field examinations for incidentalomas that abut or compress the optic nerve and chiasm and follow-up endocrine testing for macroincidentalomas.[16]

Ectopic pituitary adenoma

An ectopic (occurring in an abnormal place) pituitary adenoma is a rare type of tumor which occurs outside of the sella turcica, most often in the sphenoid sinus,[17] suprasellar region, nasopharynx and the cavernous sinuses.[18]

Metastases to the pituitary gland

Carcinomas that metastasize into the pituitary gland are uncommon and typically seen in the elderly,[19][20] with lung and breast cancers being the most prevalent,[21] In breast cancer patients, metastases to the pituitary gland occur in approximately 6-8% of cases.[22]

Symptomatic pituitary metastases account for only 7% of reported cases. In those who are symptomatic Diabetes insipidus often occurs with rates approximately 29-71%. Other commonly reported symptoms include anterior pituitary dysfunction, visual field defects, headache/pain, and ophthalmoplegia.[23]

Risk factors

Multiple endocrine neoplasia

Adenomas of the anterior pituitary gland are a major clinical feature of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), a rare inherited endocrine syndrome that affects 1 person in every 30,000. MEN causes various combinations of benign or malignant tumors in various glands in the endocrine system or may cause the glands to become enlarged without forming tumors. It often affects the parathyroid glands, pancreatic islet cells, and anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. MEN1 may also cause non-endocrine tumors such as facial angiofibromas, collagenomas, lipomas, meningiomas, ependymomas, and leiomyomas. Approximately 25 percent of patients with MEN1 develop pituitary adenomas.[24][25]

Carney complex

Carney complex (CNC), also known as LAMB syndrome[26] and NAME syndrome[26] is an autosomal dominant condition comprising myxomas of the heart and skin, hyperpigmentation of the skin (lentiginosis), and endocrine overactivity and is distinct from Carney's triad.[27][28] Approximately 7% of all cardiac myxomas are associated with Carney complex.[29] Patients with CNC develop growth hormone (GH)-producing pituitary tumors and in some instances these same tumors also secrete prolactin. There are however no isolated prolactinomas or any other type of pituitary tumor. In some patients with CNC, the pituitary gland is characterized by hyperplastic areas with the hyperplasia most likely preceding the formation of GH-producing adenomas.[30]

Familial isolated pituitary adenoma

Familial isolated pituitary adenoma (FIPA) is a term that used to identify a condition that displays an autosomal dominant inheritance and is characterised by the presence of two or more related patients affected by adenomas of the pituitary gland only, with no other associated symptoms that occur in Multiple endocrine neoplasia Type 1 or Carney complex.[31][32]

Symptoms

Physical

Hormone secreting pituitary adenomas cause one of several forms of hyperpituitarism. The specifics depend on the type of hormone. Some tumors secrete more than one hormone, the most common combination being GH and prolactin.

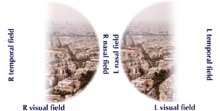

A pituitary adenoma may present with visual field defects, classically bitemporal hemianopia. It arises from the compression of the optic nerve by the tumor. The specific area of the visual pathway at which compression by these tumours occurs is at the optic chiasma.

The anatomy of this structure causes pressure on it to produce a defect in the temporal visual field on both sides, a condition called bitemporal hemianopia. If originating superior to the optic chiasm, more commonly in a craniopharyngioma of the pituitary stalk, the visual field defect will first appear as bitemporal inferior quadrantanopia, if originating inferior to the optic chiasm the visual field defect will first appear as bitemporal superior quadrantanopia. Lateral expansion of a pituitary adenoma can also compress the abducens nerve, causing a lateral rectus palsy.

Also, a pituitary adenoma can cause symptoms of increased intracranial pressure.

Prolactinomas often start to give symptoms especially during pregnancy, when the hormone progesterone increases the tumor's growth rate.

Various types of headaches are common in patients with pituitary adenomas. The adenoma may be the prime causative factor behind the headache or may serve to exacerbate a headache caused by other factors. Amongst the types of headaches experienced are both chronic and episodic migraine, and more uncommonly various unilateral headaches; primary stabbing headache,[33] short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT)[34] - another type of stabbing headache characterized by short stabs of pain -, cluster headache,[35] and hemicrania continua (HS).[36]

Psychiatric

Various psychiatric manifestations have been associated with pituitary disorders including pituitary adenomas. Psychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety[37] apathy, emotional instability, easy irritability and hostility have been noted.[38]

One study, which compared the prevalence of microadenomas in those dying from suicide and those who died from other causes, suggests that pituitary adenomas belong to suicide risk factors.[14]

Complications

- Acromegaly is a syndrome that results when the anterior pituitary gland produces excess growth hormone (GH). Approximately 90-95% of acromegaly cases are caused by a pituitary adenoma and it most commonly affects middle aged adults,[39] Acromegly can result in severe disfigurement, serious complicating conditions, and premature death if unchecked. The disease which is often also associated with gigantism, is difficult to diagnose in the early stages and is frequently missed for many years, until changes in external features, especially of the face, become noticeable with the median time from the development of initial symptoms to diagnosis being twelve years.[40]

- Cushing's syndrome is a hormonal disorder that causes hypercortisolism, which is elevated levels of cortisol in the blood. Cushing's disease (CD) is the most frequent cause of Cushing's syndrome, responsible for approximately 70% of cases.[41] CD results when a pituitary adenoma causes excessive secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) that stimulates the adrenal glands to produce excessive amounts of cortisol.[42]

- Cushing's disease may cause fatigue, weight gain, fatty deposits around the abdomen and lower back (truncal obesity) and face ("moon face"), stretch marks (striae) on the skin of the abdomen, thighs, breasts and arms, hypertension, glucose intolerance and various infections. In women it may cause excessive growth of facial hair (hirsutism) and in men erectile dysfunction. Psychiatric manifestations may include depression, anxiety, easy irritability and emotional instability. It may also result in various cognitive difficulties.

- Hyperpituitarism is a disease of the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland which is usually caused by a functional pituitary adenoma and results in hypersecretion of adenohypophyseal hormones such as growth hormone; prolactin; thyrotropin; luteinizing hormone; follicle stimulating hormone; and adrenocorticotropic hormone.

- Pituitary apoplexy is a condition that occurs when pituitary adenomas suddenly hemorrhage internally, causing a rapid increase in size or when the tumor outgrows its blood supply which causes tissue necrosis and subsequent swelling of the dead tissue. Pituitary apoplexy often presents with visual loss and sudden onset headache and requires timely treatment often with corticosteroids and if necessary surgical intervention.[43]

- Central diabetes insipidus is caused by diminished production of the antidiuretic hormone vasopressin that causes severe thirst and excessive production of very dilute urine (polyuria) which can lead to dehydration. Vasopressin is produced in the hypothalamus and is then transported down the pituitary stalk and stored in the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland which then secretes it into the bloodstream.[44]

- The diagnosis of CDI is based on the results of urine and blood tests, and a water deprivation test which tests the body's ability to concentrate urine. CDI is often treated with desmopressin acetate a synthetic vasopressin known as DDAVP administered via nasal spray.

Diagnosis and workup

Diagnosis of pituitary adenoma can be made, or at least suspected, by a constellation of related symptoms presented above.

Tumors which cause visual difficulty are likely to be a macroadenoma greater than 10 mm in diameter; tumors less than 10 mm are microadenoma.

The differential diagnosis includes pituitary tuberculoma, especially in developing countries and in immumocompromised patients.[45] The diagnosis is confirmed by testing hormone levels, and by radiographic imaging of the pituitary (for example, by CT scan or MRI).

Treatment

Treatment options depend on the type of tumor and on its size:

- Prolactinomas are most often treated with bromocriptine or more recently, cabergoline or quinagolide which decrease tumor size as well as alleviates symptoms, both dopamine agonists, and followed by serial imaging to detect any increase in size. Treatment where the tumor is large can be with radiation therapy or surgery, and patients generally respond well. Efforts have been made to use a progesterone antagonist for the treatment of prolactinomas, but so far have not proved successful.

- Somatotrophic adenomas respond to octreotide, a long-acting somatostatin analog, in many but not all cases according to a review of the medical literature. Unlike prolactinomas, thyrotrophic adenomas characteristically respond poorly to dopamine agonist treatment.[12]

- Surgery is a common treatment for pituitary tumors. Trans-sphenoidal adenectomy surgery can often remove the tumor without affecting other parts of the brain. Endoscopic surgery has become common recently.[46]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Ezzat, Shereen; Asa, Sylvia L.; Couldwell, William T.; Barr, Charles E.; Dodge, William E.; Vance, Mary Lee; McCutcheon, Ian E. (2004). "The prevalence of pituitary adenomas". Cancer 101 (3): 613–9. doi:10.1002/cncr.20412. PMID 15274075.

- ↑ Asa, Sylvia L. (2008). "Practical Pituitary Pathology: What Does the Pathologist Need to Know?". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 132 (8): 1231–40. doi:10.1043/1543-2165(2008)132[1231:PPPWDT]2.0.CO;2 (inactive September 30, 2013). PMID 18684022.

- ↑ Hyperthyroidism unmasked several years after the medical and radiosurgical treatment of an invasive macroprolactinoma inducing hypopituitarism: a case report. L Foppiani, A Ruelle, P Cavazzani, P del Monte - Cases journal, 2009

- ↑ Daly, A. F.; Rixhon, M.; Adam, C.; Dempegioti, A.; Tichomirowa, M. A.; Beckers, A. (2006). "High Prevalence of Pituitary Adenomas: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Province of Liege, Belgium". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 91 (12): 4769–75. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-1668. PMID 16968795.

- ↑ Dhruve

- ↑ Nussey, S.S; S.A. (2001). Endocrinology: An Integrated Approach. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers. ISBN 978-0-203-45043-7.

- ↑ Zhao, Yangu; Mailloux, Christina M.; Hermesz, Edit; Palkóvits, Miklos; Westphal, Heiner (2010). "A role of the LIM-homeobox gene Lhx2 in the regulation of pituitary development". Developmental Biology 337 (2): 313–23. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.002. PMC 2832476. PMID 19900438.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ironside, J W (2003). "Best Practice No 172: Pituitary gland pathology". Journal of Clinical Pathology 56 (8): 561–8. doi:10.1136/jcp.56.8.561. PMC 1770019. PMID 12890801.

- ↑ Asa, S. L.; Ezzat, S (1998). "The Cytogenesis and Pathogenesis of Pituitary Adenomas". Endocrine Reviews 19 (6): 798–827. doi:10.1210/er.19.6.798. PMID 9861546.

- ↑ Scanarini, M.; Mingrino, S. (1980). "Functional classification of pituitary adenomas". Acta Neurochirurgica 52 (3–4): 195–202. doi:10.1007/BF01402074. PMID 7424602.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Reddy, S. Sethu K.; Hamrahian, Amir H. (2009). "Pituitary Disorders and Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Syndromes". In Stoller, James K.; Michota, Franklin A.; Mandell, Brian F. The Cleveland Clinic Foundation Intensive Review of Internal Medicine. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 525–35. ISBN 0-7817-9079-4.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Chanson, Philippe; Weintraub, BD; Harris, AG (1993). "Octreotide Therapy for Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone-Secreting Pituitary Adenomas: A Follow-up of 52 Patients". Annals of Internal Medicine 119 (3): 236–40. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-3-199308010-00010. PMID 8323093.

- ↑ Fernandez-Balsells, M. M.; Murad, M. H.; Barwise, A.; Gallegos-Orozco, J. F.; Paul, A.; Lane, M. A.; Lampropulos, J. F.; Natividad, I.; Perestelo-Perez, L.; Ponce De Leon-Lovaton, P. G.; Erwin, P. J.; Carey, J.; Montori, V. M. (2011). "Natural History of Nonfunctioning Pituitary Adenomas and Incidentalomas: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 96 (4): 905–12. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-1054. PMID 21474687.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Furgal-Borzych, Alicja; Lis, Grzegorz J.; Litwin, Jan A.; Rzepecka-Wozniak, Ewa; Trela, Franciszek; Cichocki, Tadeusz (2007). "Increased Incidence of Pituitary Microadenomas in Suicide Victims". Neuropsychobiology 55 (3–4): 163–6. doi:10.1159/000106475. PMID 17657169.

- ↑ Forensic Neuropathology p. 137 By Jan E. Leestma

- ↑ Freda, P. U.; Beckers, A. M.; Katznelson, L.; Molitch, M. E.; Montori, V. M.; Post, K. D.; Vance, M. L.; Endocrine, Society (2011). "Pituitary Incidentaloma: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 96 (4): 894–904. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-1048. PMID 21474686.

- ↑ Thompson, Lester D. R.; Seethala, Raja R.; Müller, Susan (2012). "Ectopic Sphenoid Sinus Pituitary Adenoma (ESSPA) with Normal Anterior Pituitary Gland: A Clinicopathologic and Immunophenotypic Study of 32 Cases with a Comprehensive Review of the English Literature". Head and Neck Pathology 6 (1): 75–100. doi:10.1007/s12105-012-0336-9. PMC 3311955. PMID 22430769.

- ↑ Leon Barnes: Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours; p.100: World Health Organization; (2005) ISBN 92-832-2417-5

- ↑ Weil, Robert J. (2002). "Pituitary Metastasis". Archives of Neurology 59 (12): 1962–3. doi:10.1001/archneur.59.12.1962. PMID 12470187.

- ↑ Bret, Philippe; Jouvet, Anne; Madarassy, Gabor; Guyotat, Jacques; Trouillas, Jacqueline (2001). "Visceral cancer metastasis to pituitary adenoma: Report of two cases". Surgical Neurology 55 (5): 284–90. doi:10.1016/S0090-3019(01)00447-5. PMID 11516470.

- ↑ Morita, Akio; Meyer, Fredric B.; Laws Jr, Edward R. (1998). "Symptomatic pituitary metastases". Journal of Neurosurgery 89 (1): 69–73. doi:10.3171/jns.1998.89.1.0069. PMID 9647174.

- ↑ Daniel R. Fassett, M.D.; William T. Couldwell, M.D., PhD;Medscape:Metastases to the Pituitary Gland

- ↑ Komninos, J. (2004). "Tumors Metastatic to the Pituitary Gland: Case Report and Literature Review". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 89 (2): 574–80. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-030395. PMID 14764764.

- ↑ Newey, Paul J.; Thakker, Rajesh V. (2011). "Role of Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 Mutational Analysis in Clinical Practice". Endocrine Practice 17: 8–17. doi:10.4158/EP10379.RA. PMID 21454234.

- ↑ Marini, Francesca; Falchetti, Alberto; Luzi, Ettore; Tonelli, Francesco; Maria Luisa, Brandi (2009). "Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (MEN1) Syndrome". In Riegert-Johnson, Douglas L. Cancer Syndromes. PMID 21249756.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Carney Syndrome at eMedicine

- ↑ Carney, J. Aidan; Gordon, Hymie; Carpenter, Paul C.; Shenoy, B. Vittal; W. Go, Vay Liang (1985). "The Complex of Myxomas, Spotty Pigmentation, and Endocrine Overactivity". Medicine 64 (4): 270–83. doi:10.1097/00005792-198507000-00007. PMID 4010501.

- ↑ McCarthy, PM; Piehler, JM; Schaff, HV; Pluth, JR; Orszulak, TA; Vidaillet Jr, HJ; Carney, JA (1986). "The significance of multiple, recurrent, and 'complex' cardiac myxomas". The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 91 (3): 389–96. PMID 3951243.

- ↑ Reynen, Klaus (1995). "Cardiac Myxomas". New England Journal of Medicine 333 (24): 1610–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM199512143332407. PMID 7477198.

- ↑ Stergiopoulos, Sotirios G.; Abu-Asab, Mones S.; Tsokos, Maria; Stratakis, Constantine A. (2004). "Pituitary Pathology in Carney Complex Patients". Pituitary 7 (2): 73–82. doi:10.1007/s11102-005-5348-y. PMC 2366887. PMID 15761655.

- ↑ Daly, Adrian F; Vanbellinghen, Jean-François; Beckers, Albert (2007). "Characteristics of Familial Isolated Pituitary Adenomas". Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism 2 (6): 725–33. doi:10.1586/17446651.2.6.725.

- ↑ Daly, A. F.; Jaffrain-Rea, ML; Ciccarelli, A; Valdes-Socin, H; Rohmer, V; Tamburrano, G; Borson-Chazot, C; Estour, B; Ciccarelli, E; Brue, T; Ferolla, P; Emy, P; Colao, A; De Menis, E; Lecomte, P; Penfornis, F; Delemer, B; Bertherat, J; Wémeau, JL; De Herder, W; Archambeaud, F; Stevenaert, A; Calender, A; Murat, A; Cavagnini, F; Beckers, A (2006). "Clinical Characterization of Familial Isolated Pituitary Adenomas". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 91 (9): 3316–23. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-2671. PMID 16787992.

- ↑ Levy, M. J.; Matharu, MS; Meeran, K; Powell, M; Goadsby, PJ (2005). "The clinical characteristics of headache in patients with pituitary tumours". Brain 128 (8): 1921–30. doi:10.1093/brain/awh525. PMID 15888539.

- ↑ Matharu, M S; Levy, MJ; Merry, RT; Goadsby, PJ (2003). "SUNCT syndrome secondary to prolactinoma". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 74 (11): 1590–2. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.11.1590. PMC 1738244. PMID 14617728.

- ↑ Milos, Peter; Havelius, Uif; Hindfelt, Bengt (1996). "Clusterlike Headache in a Patient with a Pituitary Adenoma. With a Review of Literature". Headache: the Journal of Head and Face Pain 36 (3): 184–8. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.1996.3603184.x. PMID 8984093.

- ↑ Levy, M. J.; Matharu, M. S.; Goadsby, P. J. (2003). "Prolactinomas, dopamine agonists and headache: Two case reports". European Journal of Neurology 10 (2): 169–73. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00549.x. PMID 12603293.

- ↑ Sievers, C; Ising, M; Pfister, H; Dimopoulou, C; Schneider, H J; Roemmler, J; Schopohl, J; Stalla, G K (2008). "Personality in patients with pituitary adenomas is characterized by increased anxiety-related traits: Comparison of 70 acromegalic patients with patients with non-functioning pituitary adenomas and age- and gender-matched controls". European Journal of Endocrinology 160 (3): 367–73. doi:10.1530/EJE-08-0896. PMID 19073833.

- ↑ Weitzner, M. A.; Kanfer, S; Booth-Jones, M (2005). "Apathy and Pituitary Disease: It Has Nothing to Do with Depression". Journal of Neuropsychiatry 17 (2): 159–66. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.17.2.159. PMID 15939968.

- ↑ "Acromegaly and Gigantism". Merck.com. Retrieved 2010-10-26.

- ↑ Nabarro, J. D. N. (1987). "Acromegaly". Clinical Endocrinology 26 (4): 481–512. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1987.tb00805.x. PMID 3308190.

- ↑ Cushing’s Syndrome at The National Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service. July 2008. In turn citing: Nieman, Lynnette K.; Ilias, Ioannis (2005). "Evaluation and treatment of Cushing's syndrome". The American Journal of Medicine 118 (12): 1340–6. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.059. PMID 16378774.

- ↑ Kirk Jr, Lawrence F; Hash, Robert B; Katner, Harold P; Jones, Tom (2000). "Cushing's Disease: Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Evaluation". American Family Physician 62 (5): 1119–27, 1133–4. PMID 10997535.

- ↑ Biousse, V; Newman, NJ; Oyesiku, NM (2001). "Precipitating factors in pituitary apoplexy". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 71 (4): 542–5. doi:10.1136/jnnp.71.4.542. PMC 1763528. PMID 11561045.

- ↑ Maghnie, Mohamad (2003). "Diabetes insipidus". Hormone Research 59: 42–54. doi:10.1159/000067844. PMID 12566720.

- ↑ Saini, KS; Patel, AL; Shaikh, WA; Magar, LN; Pungaonkar, SA (2007). "Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in pituitary tuberculoma". Singapore Medical Journal 48 (8): 783–6. PMID 17657390.

- ↑ American Cancer Society. "Detailed guide: Pituitary tumor. Surgery." Retrieved January 10, 2008

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pituitary adenoma. |

- Cancer.gov: pituitary tumors

- Cleveland Clinic: Evaluation and management of pituitary incidentalomas

- The Pituitary Foundation

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

_GH_production.jpg)

_GH_production.jpg)