Piraeus Lion

The Piraeus Lion is one of four lion statues on display at the Venetian Arsenal, where it was displayed as a symbol of Venice's patron saint, Saint Mark. It was originally located in Piraeus, the harbour of Athens. It was looted by Venetian naval commander Francesco Morosini in 1687 as plunder taken in the Great Turkish War against the Ottoman Empire, during which the Venetians besieged Athens and Morosini's cannons caused damage to the Parthenon only matched by his subsequent looting.[1] Copies of the statue can also be seen at the Piraeus Archaeological Museum and the Swedish Museum of National Antiquities in Stockholm.

The lion was a famous landmark in Piraeus, having stood there since the 1st or 2nd century AD. Its prominence was such that the port was given the name Porto Leone ("Lion Port") by the Italians, who had long forgotten the port's original name.[2] It is depicted in a sitting pose, with a hollow throat and the mark of a pipe (now lost) running down its back; this suggests that it was originally used as a fountain.[3] This is consistent with the description of the statue from the 1670s, which said that water flowed from the lion's mouth into a cistern at its feet.[4]

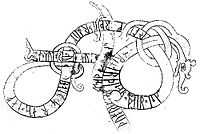

The statue, which is made of white marble and stands some 3 m (9 ft.) high, is particularly noteworthy for having been defaced some time in the second half of the 11th century by Scandinavians who carved two lengthy runic inscriptions into the shoulders and flanks of the lion.[5] The runes are carved in the shape of an elaborate lindworm dragon-headed scroll, in much the same style as on runestones in Scandinavia.[6] The carvers of the runes were almost certainly Varangians, Scandinavian mercenaries in the service of the Byzantine Emperor.

Inscriptions and translations

_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall'Orto%2C_3-Aug-2007.jpg)

The inscriptions were not recognised as runes until the Swedish diplomat Johan David Åkerblad identified them at the end of the 18th century. They are in the shape of a lindworm (a flightless dragon with serpentine body and two or no legs) and were first translated in the mid-19th century by Carl Christian Rafn, the Secretary of the Kongelige Nordiske Oldskrift-Selskab (Royal Society of Nordic Antiquaries).[7] The inscriptions are heavily eroded due to weathering and air pollution, making many of the individual runes barely legible. This has required translators to reconstruct some of the runes, filling in the blanks to determine what words they represented.

There have been several attempts to decipher and translate the text. Below follow Hrafn's early attempt (1854) and Eric Brate's attempt (1914), which is considered to be the most successful one.[8]

Rafn's translation

Rafn's attempt is as follows, with the legible letters shown in bold and the reconstructed ones unbolded:[9][10]

Right side of the lion:

- ASMUDR : HJU : RUNAR : ÞISAR : ÞAIR : ISKIR : AUK: ÞURLIFR : ÞURÞR : AUK : IVAR : AT : BON : HARADS : HAFA : ÞUAT : GRIKIAR : UF : HUGSAÞU : AUK : BANAÞU :

- Asmund cut these runes with Asgeir and Thorleif, Thord and Ivar, at the request of Harold the Tall, though the Greeks considered about and forbade it.

Left side of the lion:

- HAKUN : VAN: ÞIR : ULFR : AUK : ASMUDR : AUK : AURN : HAFN : ÞESA : ÞIR : MEN : LAGÞU : A : UK : HARADR : HAFI : UF IABUTA : UPRARSTAR : VEGNA : GRIKIAÞIÞS : VARÞ : DALKR : NAUÞUGR : I : FIARI : LAÞUM : EGIL : VAR : I : FARU : MIÞ : RAGNARR : TIL : RUMANIU . . . . AUK : ARMENIU :

Some have tried to trace Harald Hardrade's name on the inscription, but the time it was carved does not coincide with his time in the service of the emperor.[11]

Erik Brate's translation

Erik Brate's interpretation from 1914 is considered to be the most successful one.[8]

|

|

Popular culture

- The Piraeus Lion appears as a creature in God of War: Ghost of Sparta. Kratos fights the Piraeus Lion after a Dissenter had released it.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arsenale (Venice) - First Ancient Greek lion. |

- Berezan' Runestone

- Greece Runestones

- Italy Runestones

- Runic inscriptions in Hagia Sophia

Literature

- sv:Sven B.F. Jansson, "Pireuslejonets runor", Nordisk Tidskrift för vetenskap konst och industri, utgiven av Letterstedtska Föreningen. Stockholm (1984).

References

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, Athens, The Acropolis, p.6/20, 2008, O.Ed.

- ↑ Goette, Hans Rupprecht (2001), Athens, Attica and the Megarid: An Archaeological Guide. Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 0-415-24370-X

- ↑ Ellis, Henry (1833). The British Museum. Elgin and Phigaleian Marbles. British Museum. p. 36.

- ↑ Jarring, Gunnar (1978). "Evliya Celebi och Marmorlejonet från Pireus". Fornvännen (Swedish National Heritage Board) 85: 1–4. ISSN 1404-9430. Retrieved 5 September 2010..

- ↑ Kendrick, Thomas D. (2004). A History of the Vikings. Courier Dover Publications. p. 176. ISBN 0-486-43396-X

- ↑ "The Book of THoTH (Leaves of Wisdom) — Dragon" (notes), URL: BT-Dragon.

- ↑ Rafn, Carl Christian (1857). "En Nordisk Runeindskrift i Piræus, med Forklaring af C. C. Rafn". Antiquarisk Tidsskrift: Udgivet af det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskrift-Selskab 1855-57. pp. 3–69.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Pritsak, Omeljan. (1981). The Origin of Rus'. Cambridge, Mass.: Distributed by Harvard University Press for the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 348. ISBN 0-674-64465-4

- ↑ A. Craig Gibson, "Runic Inscriptions: Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian", in Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, p. 130. Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 1902

- ↑ Rafn, Carl Christian (1856). "Inscription runique du Pirée - Runeindskrift i Piraeeus", Impr. de Thiele

- ↑ Heath, Ian (1985). The Vikings Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-565-0

Coordinates: 45°26′5.22″N 12°20′59.34″E / 45.4347833°N 12.3498167°E