Physical quantity

A physical quantity (or "physical magnitude") is a physical property of a phenomenon, body, or substance, that can be quantified by measurement.[1]

Extensive and intensive quantities

An extensive quantity is equal to the sum of that quantity for all of its constituent subsystems; examples include volume, mass, and electric charge. For instance, if an object has mass m1 and another has mass m2 then a system simply comprising those two objects will have a mass of m1 + m2.

An intensive quantity is independent of the extent of the system; quantities such as temperature, pressure, and density are examples. To illustrate, if two objects having a given temperature are combined, together they still have the same temperature (not twice the temperature).

There are also physical quantities that can be classified as neither extensive nor intensive, for example an extensive quantity with a nonlinear operator applied, such as the square of volume.[2]

Symbols, nomenclature

General: Symbols for quantities should be chosen according to the international recommendations from ISO 80000, the IUPAP red book and the IUPAC green book. For example, the recommended symbol for the physical quantity 'mass' is m, and the recommended symbol for the quantity 'charge' is Q.

Subscripts and indices

Subscripts are used for two reasons, to simply attach a name to the quantity or associate it with another quantity, or represent a specific vector, matrix, or tensor component.

- Name reference: The quantity has a subscripted or superscripted single letter, a number of letters, or an entire word, to specify what concept or entity they refer to, and tend to be written in upright roman typeface rather than italic while the quantity is in italic. For instance Ek or Ekinetic is usually used to denote kinetic energy and Ep or Epotential is usually used to denote potential energy.

- Quantity reference: The quantity has a subscripted or superscripted single letter, a number of letters, or an entire word, to specify what measurement/s they refer to, and tend to be written in italic rather than upright roman typeface while the quantity is also in italic. For example cp or cisobaric is heat capacity at constant pressure.

- Note the difference in the style of the subscripts: k and p are abbreviations of the words kinetic and potential, whereas p (italic) is the symbol for the physical quantity pressure rather than an abbreviation of the word "pressure".

- Indices: These are quite apart from the above, their use is for mathematical formalism, see Index notation.

Scalars: Symbols for physical quantities are usually chosen to be a single letter of the Latin or Greek alphabet, and are printed in italic type.

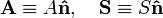

Vectors: Symbols for physical quantities that are vectors are in bold type, underlined or with an arrow above. If, e.g., u is the speed of a particle, then the straightforward notation for its velocity is u, u, or  .

.

Numbers and elementary functions

Numerical quantities, even those denoted by letters, are usually printed in roman (upright) type, though sometimes can be italic. Symbols for elementary functions (circular trigonometric, hyperbolic, logarithmic etc.), changes in a quantity like Δ in Δy or operators like d in dx, are also recommended to be printed in roman type.

- Examples

- real numbers are as usual, such as 1 or √2,

- e for the base of natural logarithm,

- i for the imaginary unit,

- π for 3.14159265358979323846264338327950288...

- δx, Δy, dz,

- sin α, sinh γ, log x

Units and dimensions

Units

Most physical quantities include a unit, but not all - some are dimensionless. Neither the name of a physical quantity, nor the symbol used to denote it, implies a particular choice of unit, though SI units are usually preferred and assumed today due to their ease of use and all-round applicability. For example, a quantity of mass might be represented by the symbol m, and could be expressed in the units kilograms (kg), pounds (lb), or daltons (Da).

Dimensions

The notion of physical dimension of a physical quantity was introduced by Joseph Fourier in 1822.[3] By convention, physical quantities are organized in a dimensional system built upon base quantities, each of which is regarded as having its own dimension.

Base quantities

Base Quantities are those quantities on the basics of which other quantities can be expressed. The seven base quantities of the International System of Quantities (ISQ) and their corresponding SI units and dimensions are listed in the following table. Other conventions may have a different number of fundamental units (e.g. the CGS and MKS systems of units).

| Quantity name/s | (Common) Quantity symbol/s | SI unit name | SI unit symbol | Dimension symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length, width, height, depth | a, b, c, d, h, l, r, s, w, x, y, z | metre | m | [L] |

| Time | t | second | s | [T] |

| Mass | m | kilogram | kg | [M] |

| Temperature | T, θ | kelvin | K | [Θ] |

| Amount of substance, number of moles | n | mole | mol | [N] |

| Electric current | i, I | ampere | A | [I] |

| Luminous intensity | Iv | candela | cd | [J] |

| Plane angle | α, β, γ, θ, φ, χ | radian | rad | dimensionless |

| Solid angle | ω, Ω | steradian | sr | dimensionless |

The last two angular units; plane angle and solid angle are subsidiary units used in the SI, but treated dimensionless. The subsidiary units are used for convenience to differentiate between a truly dimensionless quantity (pure number) and an angle, which are different measurements.

General derived quantities

Space

Important applied base units for space and time are below. Area and volume are of course derived from length, but included for completeness as they occur frequently in many derived quantities, in particular densities.

| (Common) Quantity name/s | (Common) Quantity symbol | SI unit | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Spatial) position (vector) | r, R, a, d | m | [L] |

| Angular position, angle of rotation (can be treated as vector or scalar) | θ, θ | rad | dimensionless |

| Area, cross-section | A, S, Ω | m2 | [L]2 |

| Vector area (Magnitude of surface area, directed normal to tangential plane of surface) |  |

m2 | [L]2 |

| Volume | τ, V | m3 | [L]3 |

Densities, flows, gradients, and moments

Important and convenient derived quantities such as densities, fluxes, flows, currents are associated with many quantities. Sometimes different terms such as current density and flux density, rate, frequency and current, are used interchangeably in the same context, sometimes they are used uniqueley.

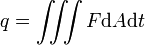

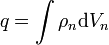

To clarify these effective template derived quantities, we let q be any quantity within some scope of context (not necessarily base quantities) and present in the table below some of the most commonly used symbols where applicable, their definitions, usage, SI units and SI dimensions - where [q] is the dimension of q.

For time derivatives, specific, molar, and flux densities of quantities there is no one symbol, nomenclature depends on subject, though time derivatives can be generally written using overdot notation. For generality we use qm, qn, and F respectively. No symbol is necessarily required for the gradient of a scalar field, since only the nabla/del operator ∇ or grad needs to be written. For spatial density, current, current density and flux, the notations are common from one context to another, differing only by a change in subscripts.

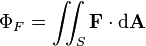

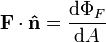

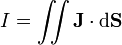

For current density,  is a unit vector in the direction of flow, i.e. tangent to a flowline. Notice the dot product with the unit normal for a surface, since the amount of current passing through the surface is reduced when the current is not normal to the area. Only the current passing perpendicular to the surface contributes to the current passing through the surface, no current passes in the (tangential) plane of the surface.

is a unit vector in the direction of flow, i.e. tangent to a flowline. Notice the dot product with the unit normal for a surface, since the amount of current passing through the surface is reduced when the current is not normal to the area. Only the current passing perpendicular to the surface contributes to the current passing through the surface, no current passes in the (tangential) plane of the surface.

The calculus notations below can be used synonymously.

If X is a n-variable function  , then:

, then:

- Differential The differential n-space volume element is

,

,

- Integral: The multiple integral of X over the n-space volume is

.

.

| Quantity | Typical symbols | Definition | Meaning, usage | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | q | q | Amount of a property | [q] |

| Rate of change of quantity, Time derivative |  |

|

Rate of change of property with respect to time | [q] [T]−1 |

| Quantity spatial density | ρ = volume density (n = 3), σ = surface density (n = 2), λ = linear density (n = 1)

No common symbol for n-space density, here ρn is used. |

|

Amount of property per unit n-space (length, area, volume or higher dimensions) |

[q][L]-n |

| Specific quantity | qm |  |

Amount of property per unit mass | [q][L]-n |

| Molar quantity | qn |  |

Amount of property per mole of substance | [q][L]-n |

| Quantity gradient (if q is a scalar field. |  |

Rate of change of property with respect to position | [q] [L]−1 | |

| Spectral quantity (for EM waves) | qv, qν, qλ | Two definitions are used, for frequency and wavelength:

|

Amount of property per unit wavelength or frequency. | [q][L]−1 (qλ) [q][T] (qν) |

| Flux, flow (synonymous) | ΦF, F | Two definitions are used; Transport mechanics, nuclear physics/particle physics: |

Flow of a property though a cross-section/surface boundary. | [q] [T]−1 [L]−2, [F] [L]2 |

| Flux density | F |  |

Flow of a property though a cross-section/surface boundary per unit cross-section/surface area | [F] |

| Current | i, I |  |

Rate of flow of property through a cross

section/ surface boundary |

[q] [T]−1 |

| Current density (sometimes called flux density in transport mechanics) | j, J |  |

Rate of flow of property per unit cross-section/surface area | [q] [T]−1 [L]−2 |

| Moment of quantity | m, M | Two definitions can be used; q is a scalar: |

Quantity at position r has a moment about a point or axes, often relates to tendency of rotation or potential energy. | [q] [L] |

The meaning of the term physical quantity is generally well understood (everyone understands what is meant by the frequency of a periodic phenomenon, or the resistance of an electric wire). The term physical quantity does not imply a physically invariant quantity. Length for example is a physical quantity, yet it is variant under coordinate change in special and general relativity. The notion of physical quantities is so basic and intuitive in the realm of science, that it does not need to be explicitly spelled out or even mentioned. It is universally understood that scientists will (more often than not) deal with quantitative data, as opposed to qualitative data. Explicit mention and discussion of physical quantities is not part of any standard science program, and is more suited for a philosophy of science or philosophy program.

The notion of physical quantities is seldom used in physics, nor is it part of the standard physics vernacular. The idea is often misleading, as its name implies "a quantity that can be physically measured", yet is often incorrectly used to mean a physical invariant. Due to the rich complexity of physics, many different fields possess different physical invariants. There is no known physical invariant sacred in all possible fields of physics. Energy, space, momentum, torque, position, and length (just to name a few) are all found to be experimentally variant in some particular scale and system. Additionally, the notion that it is possible to measure "physical quantities" comes into question, particular in quantum field theory and normalization techniques. As infinities are produced by the theory, the actual “measurements” made are not really those of the physical universe (as we cannot measure infinities), they are those of the renormalization scheme which is expressly depended on our measurement scheme, coordinate system and metric system.

See also

- Philosophy of science

- Quantitative property

References

- ↑ Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology (JCGM), International Vocabulary of Metrology, Basic and General Concepts and Associated Terms (VIM), III ed., Pavillon de Breteuil : JCGM 200:2012 (on-line)

- ↑ Hatsopoulos G.N. and Keenan J.H. Principles of general thermodynamics, John Wiley and Sons 1965 p.19-20

- ↑ Fourier, Joseph. Théorie analytique de la chaleur, Firmin Didot, Paris, 1822. (In this book, Fourier introduces the concept of physical dimensions for the physical quantities.)

Computer implementations

- DEVLIB project in C# Language and Delphi Language

- PhysicalQuantities project in C# Language at CodePlex

- PhysicalMeasure C# library project in C# Language at CodePlex

- Ethica Measures project in C# Language at CodePlex

Sources

- Cook, Alan H. The observational foundations of physics, Cambridge, 1994. ISBN 0-521-45597-

- Essential Principles of Physics, P.M. Whelan, M.J. Hodgeson, 2nd Edition, 1978, John Murray, ISBN 0-7195-3382-1

- Encyclopaedia of Physics, R.G. Lerner, G.L. Trigg, 2nd Edition, VHC Publishers, Hans Warlimont, Springer, 2005, pp 12–13

- Physics for Scientists and Engineers: With Modern Physics (6th Edition), P.A. Tipler, G. Mosca, W.H. Freeman and Co, 2008, 9-781429-202657