Phosphopentose epimerase

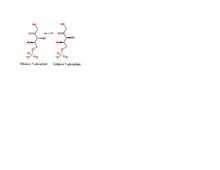

Phosphopentose epimerase (also known as ribulose-phosphate 3-epimerase and ribulose 5-phosphate 3-epimerase) is a metalloprotein that catalyzes the interconversion between D-ribulose 5-phosphate and D-xylulose 5-phosphate.[1]

- D-ribulose 5-phosphate

D-xylulose 5-phosphate

D-xylulose 5-phosphate

This reversible conversion is required for carbon fixation in plants – through the Calvin cycle – and for the nonoxidative phase of the pentose phosphate pathway.[2][3] This enzyme has also been implicated in additional pentose and glucuronate interconversions.

Family

Phosphopentose epimerase belongs to two protein families of increasing hierarchy. This enzyme belongs to the isomerase family which acts on carbohydrates and their derivatives.[1] In addition, the Structural Classification of Proteins database has defined the “ribulose phosphate binding” superfamily for which this epimerase is a member.[1] Other proteins included in this superfamily are 5‘-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC), and 3-keto-l-gulonate 6-phosphate decarboxylase (KGPDC).

Structure

Overall

Crystallographic studies have helped elucidate the apoenzyme structure of phosphopentose epimerase. Results of these studies have shown that this enzyme exists as a homodimer in solution.[4][5] Furthermore, Phosphopentose epimerase folds into a (β/α)8 triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) barrel that includes loops.[2] The core barrel is composed of 8 parallel strands that make up the central beta sheet, with helices located in between consecutive strands. The loops in this structure have been known to regulate substrate specificities. Specifically, the loop that connects helix α6 with strand β6 caps the active site upon binding of the substrate.[2]

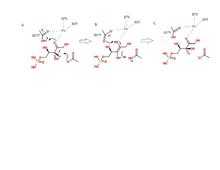

As previously mentioned, Phosphopentose epimerase is a metalloenzyme. It requires a cofactor for functionality and binds one divalent metal cation per subunit.[6] This enzyme has been shown to use Zn2+ predominantly for catalysis, along with Co2+ and Mn2+.[2] However, human phosphopentose epimerase – which is encoded by the RPE gene - differs in that it binds Fe2+ predominantly in catalysis. Fe2+ is octahedrally coordinated and stabilizes the 2,3-enediolate reaction intermediate observed in the figure.[2]

Active Site

The β6/α6 loop region interacts with the substrate and regulates access to the active site. Phe147, Gly148, and Ala149 of this region cap the active site once binding has occurred. In addition, the Fe2+ ion is coordinated to His35, His70, Asp37, Asp175, and oxygens O2 and O3 of the substrate.[2] The binding of substrate atoms to the iron cation helps stabilize the complex during catalysis. Mutagenesis studies have also indicated that two aspartic acids are located within the active site and help mediate catalysis through a 1,1-proton transfer reaction.[1] The aspartic acids are the acid/base catalysts. Lastly, once the ligand is attached to the active site, a series of methionines (Met39, Met72, and Met141) restrict further movement through constriction.[7]

Mechanism

Phosphopentose utilizes an acid/base type of catalytic mechanism. The reaction proceeds in such a way that trans-2,3-enediol phosphate is the intermediate.[8][9] The two aspartic acids mentioned above act as proton donors and acceptors. Asp37 and Asp175 are both hydrogen bonded to the iron cation in the active site.[2] When Asp37 is deprotonated, it attacks a proton on the third carbon of D-ribulose 5-phosphate, which forms the intermediate.[10] In a concerted step, as Asp37 grabs a proton, the carbonyl bond on the substrate grabs a second proton from Asp175 to form a hydroxyl group. The iron complex helps stabilize any additional charges. It is C3 of D-ribulose 5-phosphate which undergoes this epimerization, forming D-xylulose 5-phosphate.[7] The mechanism is clearly demonstrated in the figure.

Biological Function

Calvin Cycle

Electron microscopy experiments in plants have shown that phosphopentose epimerase localizes to the thykaloid membrane of chloroplasts.[11] This epimerase participates in the third phase of the Calvin cycle, which involves the regeneration of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate. RuBP is the acceptor of the CO2 in the first step of the pathway, which suggests that phosphopentose epimerase regulates flux through the Calvin cycle. Without the regeneration of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate, the cycle will be unable to continue. Therefore, xylulose 5-phosphate is reversibly converted into ribulose 5-phosphate by this epimerase. Subsequently, phosphoribulose kinase converts ribulose 5-phosphate into ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate.[10]

Pentose Phosphate Pathway

The reactions of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) take place in the cytoplasm. Phosphopentose epimerase specifically affects the nonoxidative portion of the pathway, which involves the production of various sugars and precursors.[2] This enzyme converts ribulose 5-phosphate into the appropriate epimer for the transketolase reaction, xylulose 5-phosphate.[10] Therefore, the reaction that occurs in the pentose phosphate pathway is exactly the reverse of the reaction which occurs in the Calvin cycle. The mechanism remains the same and involves the formation of an enediolate intermediate.

Due to its involvement in this pathway, phosphopentose epimerase is an important enzyme for the cellular response to oxidative stress.[2] The generation of NADPH by the pentose phosphate pathway helps protect cells against reactive oxygen species. NADPH is able to reduce glutathione, which detoxifies the body by producing H2O from H2O2.[2] Therefore, not only does phosphopentose epimerase alter flux through the PPP, but it also prevents buildup of peroxides.

Evolution

The structures of many phosphopentose epimerase analogs have been discovered through crystallographic studies.[12][13] Due to its role in the Calvin cycle and the pentose phosphate pathway, the overall structure is conserved. When the sequences of evolutionarily-distant organisms were compared, greater than 50% similarity was observed.[14] However, amino acids positioned at the dimer interface – which are involved in many intermolecular interactions – are not necessarily conserved. It is important to note that the members of the “ribulose phosphate binding” superfamily resulted from divergent evolution from a (β/α)8 - barrel ancestor.[1]

Drug Targeting and Malaria

The protozoan organism Plasmodium falciparum is a major causative agent of malaria. Phosphopentose epimerase has been implicated in the shikimate pathway, an essential pathway for the propagation of malaria.[15] As the enzyme converts ribulose 5-phosphate into xylulose 5-phosphate, the latter is further metabolized into erythrose 4-phosphate. The shikimate pathway then converts erythrose 4-phosphate into chorismate.[15] It is phosphopentose epimerase which allows Plasmodium falciparum to use erythorse 4-phosphate as a substrate. Due to this enzyme’s involvement in the shikimate pathway, phosphopentose epimerase is a potential drug target for developing antimalarials.

See also

- Phosphopentose Isomerase

- Phosphoribulose Kinase

- Pentose Phosphate Pathway

- TIM barrel

- RPE

External links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Akana, Julie; Alexander A. Fedorov, Elena Fedorov, Walter R. P. Novak, Patricia C. Babbitt , Steven C. Almo, and, and John A. Gerlt (2006). "d-Ribulose 5-Phosphate 3-Epimerase: Functional and Structural Relationships to Members of the Ribulose-Phosphate Binding (β/α)8-Barrel Superfamily". Biochemistry 8 (45): 2493–2503. doi:10.1021/bi052474m. PMID 16489742.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Liang, Wenguang; Songying Ouyang, Neil Shaw, Andrzej Joachimiak, Rongguang Zhang and Zhi-Jie Liu (2011). "Conversion of d-ribulose 5-phosphate to d-xylulose 5-phosphate: new insights from structural and biochemical studies on human RPE". The FASEB Journal 25 (2): 497–504. doi:10.1096/fj.10-171207. PMID 20923965.

- ↑ Mendz, George; Stuart Hazell (1991). "Evidence for a pentose phosphate pathway in Heliobacter pylori". FEMS Microbiology Letters (84): 331–336. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1991.tb04619.x.

- ↑ Chen, Yuh-Ru; Fred C. Hartman, Tse-Yuan S. Lu, Frank W. Larimer (1998). "d-Ribulose-5-Phosphate 3-Epimerase: Cloning and Heterologous Expression of the Spinach Gene, and Purification and Characterization of the Recombinant Enzyme.". Plant Physiology 118 (1): 199–207. doi:10.1104/pp.118.1.199. PMC 34857. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ Karmali, Amin; Alex Drake, and Neill Spencer (1983). "Purification, properties, and assay of D-ribulose 5-phosphate 3-epimerase from human erythrocytes". Biochem 211 (3): 617–623. PMC 1154406. PMID 6882362. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ "Ribulose-phosphate 3-epimerase". UniProt. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Jelakovic, S; Kopriva S., Süss K.-H., and Schulz G. E (2003). "Structure and catalytic mechanism of the cytosolic d-ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase from rice". J. Mol. Biol. 326 (1): 127–135. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01374-8. PMID 12547196.

- ↑ Das, Debajoyti (1978). Biochemistry. Academic Publishers. pp. 454–460.

- ↑ Davies, L.; Lee N., and Glaser L. (1972). "On the mechanism of the pentose phosphate epimerases.". J. Biol. 247 (18): 5862–5866. PMID 4560420. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Berg, Jeremy (2006). Biochemistry. WH Freeman and Company. pp. 570–580. ISBN 978-0-7167-8724-2.

- ↑ Chen, Y.; Larimer F. W., Serpersu E. H., and Hartman F. C. (1999). "Identification of a catalytic aspartyl residue of d-ribulose 5-phosphate 3-epimerase by site-directed mutagenesis". J. Biol. Chem 274 (4): 2132–2136. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.4.2132. PMID 9890975.

- ↑ Nowitzki, J.; Wyrich R., Westhoff P., Henze K., Schnarrenberger C., and Martin W.F. (1995). "Cloning of the amphibolic Calvin cycle/OPPP enzyme D-ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase (EC 5.1.3.1) from spinach chloroplasts: functional and evolutionary aspects.". Plant Mol. Bio. 29 (6): 1279–1291. PMID 8616224. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ Wise, E.; Akana J., Gerlt J. A., and Rayment I (2004). "Structure of d-ribulose 5-phosphate 3-epimerase from Synechocystis to 1.6 A resolution.". Acta Crystallogr 60 (Pt 9): 1687–1690. doi:10.1107/S0907444904015896. PMID 15333955.

- ↑ Teige, Markus; Stanislav Kopriva, Hermann Bauwe, and Karl-Heinz Süss (1995). Chloroplast pentose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase from potato: cloning, cDNA sequence, and tissue-specific enzyme accumulation 377 (3). pp. 349–352. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(95)01373-3. PMID 8549753.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Caruthers, J.; J. Bosch, F. Buckner, W. Van Voorhis, P. Myler, E. Worthey, C. Mehlin, E. Boni, G. DeTitta, J. Luft, A. Lauricella, O. Kalyuzhniy, L. Anderson, F. Zucker, M. Soltis, and Wim G. J. Hol (2005). "Structure of a ribulose 5-phosphate 3-epimerase from Plasmodium falciparum.". Wiley Online 62 (2): 338–342. doi:10.1002/prot.20764. PMID 16304640.

| |||||||||||||