Philippine Eagle

| Philippine Eagle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Falconiformes (or Accipitriformes, q.v.) |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Pithecophaga Ogilvie-Grant, 1896 |

| Species: | P. jefferyi |

| Binomial name | |

| Pithecophaga jefferyi Ogilvie-Grant, 1897 | |

| |

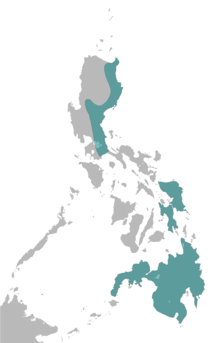

| Range in blue green | |

The Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi), also known as the Monkey-eating Eagle, is an eagle of the family Accipitridae endemic to forests in the Philippines. It has brown and white-coloured plumage, and a shaggy crest, and generally measures 86 to 102 cm (2.82 to 3.35 ft) in length and weighs 4.7 to 8.0 kilograms (10.4 to 17.6 lb). It is considered the largest of the extant eagles in the world in terms of length, with the Steller's Sea Eagle and the Harpy Eagle being larger in terms of weight and bulk.[2][3] Among the rarest and most powerful birds in the world, it has been declared the Philippine national bird.[4] It is critically endangered, mainly due to massive loss of habitat due to deforestation in most of its range. Killing a Philippine Eagle is punishable under Philippine law by 12 years in jail and heavy fines.[5]

Taxonomy

The first European to discover the species was the English explorer and naturalist John Whitehead in 1896, who observed the bird and whose servant, Juan, collected the first specimen a few weeks later.[6] The skin of the bird was sent to William Robert Ogilvie-Grant in London in 1896, who initially showed it off in a local restaurant and described the species a few weeks later.[7]

Upon its discovery, the Philippine Eagle was first called the monkey-eating eagle because of reports from natives of Bonga, Samar, where the species was first discovered, that it preyed exclusively on monkeys;[8] from these reports it gained its generic name, from the Greek pithecus ("ape or monkey") and phagus ("eater of").[9] The specific name commemorates Jeffery Whitehead, the father of John Whitehead.[7] Later studies revealed, however, that the alleged monkey-eating eagle also ate other animals, such as colugos, civets, large snakes, monitor lizards, and even large birds, such as hornbills. This, coupled with the fact that the same name applied to the African Crowned Eagle and the Central and South American Harpy Eagle, resulted in a presidential proclamation to change its name to Philippine Eagle in 1978, and in 1995 was declared a national emblem. This species has no recognized subspecies.[10]

Apart from Philippine Eagle and Monkey-eating Eagle, it has also been called the Great Philippine Eagle. It has numerous local names, including agila ("eagle"), haribon, haring ibon ("king bird") and banog ("kite").[4][11]

Evolutionary history

A study of the skeletal features in 1919 led to the suggestion that the nearest relative was the Harpy Eagle.[12] The species was included in the subfamily Harpiinae until a 2005 study of DNA sequences which identified them as not members of the group, finding instead, that the nearest relatives are snake eagles (Circaetinae), such as the Bateleur. The species has subsequently been placed in the subfamily Circaetinae.[13]

Description

The Philippine Eagle's nape is adorned with long, brown feathers that form a shaggy crest. These feathers give it the appearance of possessing a lion's mane, which in turn resembles the mythical griffin. The eagle has a dark face and a creamy-brown nape and crown. The back of the Philippine Eagle is dark brown, while the underside and underwings are white. The heavy legs are yellow, with large, powerful dark claws, and the prominent large, high-arched, deep beak is a bluish-gray. The eagle's eyes are blue-gray. Juveniles are similar to adults except their upperpart feathers have pale fringes.[14]

The Philippine Eagle is typically reported as measuring 86–102 cm (2 ft 10 in–3 ft 4 in) in total length,[3][14][15][16] but a survey of several specimens from some of the largest natural history collections in the world found the average was 95 cm (3 ft 1 in) for males and 105 cm (3 ft 5 in) for females.[17] Based on the latter measurements, this makes it the longest extant species of eagle, as the average for the female equals the maximum reported for the Harpy Eagle[16] and Steller's Sea Eagle.[3] The longest Philippine Eagle reported anywhere and the longest eagle outside of the extinct Haast's Eagle is a specimen from Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH) with a length of 112 cm (3 ft 8 in), but it had been kept in captivity[2] so may not represent the wild individuals due to differences in the food availability.[18][19] The level of sexual dimorphism in size is not certain, but the male is believed to be typically about 10% smaller than the female,[3] and this is supported by the average length provided for males and females in one source.[17] In many of the other large eagle species, the size difference between adult females and males can exceed 20%.[3] For adult Philippine Eagles, the complete weight range has been reported as 4.7 to 8 kg (10 to 18 lb),[3][20][21] while others have found the average was somewhat lower than the above range would indicate, at 4.5 kg (9.9 lb) for males and 6 kg (13 lb) for females.[17] One male (age not specified) was found to weigh 4.04 kg (8.9 lb).[22] The Philippine Eagle has a wingspan of 184 to 220 cm (6 ft 0 in to 7 ft 3 in) and a wing chord length of 57.4–61.4 cm (22.6–24.2 in).[3][23] The maximum reported weight is surpassed by two other eagles (the Harpy and Steller's Sea Eagle) and the wings are shorter than large eagles of open country (such as the White-tailed Eagle, Steller's Sea Eagle, Martial Eagle or Wedge-tailed Eagle), but are quite broad.[3] The tarsus of the Philippine Eagle ties as the longest of any eagle from 12.2 to 14.5 cm (4.8 to 5.7 in) long, which is about the same length as that of the smaller but relatively long-legged New Guinea Eagle.[3] The very large but laterally compressed bill rivals the size of the Steller's Sea Eagle's as the largest bill for an extant eagle. Its bill averages 7.22 cm (2.84 in) in length from the gape.[2] The tail is fairly long at 42–45.3 cm (16.5–17.8 in) in length,[3] while another source lists a tail length of 50 cm (20 in).[24]

The most frequently heard noises made by the Philippine Eagle are loud, high-pitched whistles ending with inflections in pitch.[25] Additionally, juveniles have been known to beg for food by a series of high-pitched calls.[14]

Distribution and habitat

The Philippine Eagle is endemic to the Philippines and can be found on four major islands: eastern Luzon, Samar, Leyte, and Mindanao. The largest number of eagles reside on Mindanao, with between 82 and 233 breeding pairs. Only six pairs are found on Samar, two on Leyte, and a few on Luzon. It can be found in Northern Sierra Madre National Park on Luzon and Mount Apo, Mount Malindang and Mount Kitanglad National Parks on Mindanao.[7][26]

This eagle is found in dipterocarp and mid-montane forests, particularly in steep areas. Its elevation ranges from the lowlands to mountains of over 1,800 metres (5,900 ft). Only an estimated 9,220 km2 (2,280,000 acres) of old-growth forest remain in the bird's range.[7] However, its total estimated range is about 146,000 km2 (56,000 sq mi).[14]

Ecology and behavior

Evolution in the Philippine islands, without other predators, made the eagles the dominant hunter in the Philippine forests. Each breeding pair requires a large home range to successfully raise a chick, thus the species is extremely vulnerable to deforestation. Earlier, the territory has been estimated at about 100 km2 (39 sq mi), but a study on Mindanao Island found the nearest distance between breeding pairs to be about 13 km (8.1 mi) on average, resulting in a circular plot of 133 km2 (51 sq mi).[27]

The species' flight is fast and agile, resembling the smaller hawks more than similar large birds of prey.[28]

Juveniles in play behavior have been observed gripping knotholes in trees with their talons and, using their tails and wings for balance, inserting their heads into tree cavities.[29] Additionally, they have been known to attack inanimate objects for practice, as well as attempt to hang upside down to work on their balance.[29] As the parents are not nearby when this occurs, they apparently do not play a role in teaching the juvenile to hunt.[29]

Life expectancy for a wild eagle is estimated to be from 30 to 60 years. A captive Philippine Eagle lived for 41 years in Rome Zoo, and it was already adult when it arrived at the zoo.[29] However, wild birds on average are believed to live shorter lives than captive birds.[29]

Diet

The Philippine Eagle was known initially as the Philippine Monkey-Eating Eagle because it was believed to feed on monkeys (the only monkey native to the Philippines is the Philippine long-tailed macaque) almost exclusively; this has proven to be inaccurate. This may be because the first examined specimen was found to have undigested pieces of a monkey in its stomach.[30] Like most predators, the Philippine Eagle is an opportunist that takes prey based on its local level of abundance and ease.[30] It is the apex predator in its range.

Prey specimens found at the eagle's nest have ranged in size from a small bat weighing 10 g (0.35 oz) to a Philippine deer weighing 14 kg (31 lb).[30] The primary prey varies from island to island depending on species availability, particularly in Luzon and Mindanao, because the islands are in different faunal regions. For example, the tree squirrel-sized Philippine flying lemurs, the preferred prey in Mindanao, are absent in Luzon.[7] The primary prey for the eagles seen in Luzon are monkeys, birds, flying foxes, giant cloud-rats Phloeomys pallidus which can weigh twice as much as flying lemurs at 2 to 2.5 kg (4.4 to 5.5 lb), and reptiles such as large snakes and lizards.[31] The flying lemur could make up an estimated 90% of the raptor's diet in some locations.[28] While the eagles generally seem to prefer flying lemurs where available, most other animals found in the Philippines, short of adult ungulates and humans, may be taken as prey. This can include Asian palm civets (12% of the diet in Mindanao), macaques, flying squirrels, tree squirrels, fruit bats, rats, birds (owls and hornbills), reptiles (snakes and monitor lizards), and even other birds of prey.[7][28][30] They have been reported to capture young pigs and small dogs.[28]

Philippine Eagles primarily use two hunting techniques. One is still-hunting, in which it watches for prey activity while sitting almost motionlessly on a branch near the canopy. The other is perch-hunting, which entails periodically gliding from one perch to another. While perch-hunting, they often work their way gradually down from the canopy on down the branches and, if not successful in find prey in their initial foray, will fly or circle back up to the top of the trees to work them again. Eagles in Mindanao often find success using the latter method while hunting flying lemurs, since they are nocturnal animals which try to use camouflage to protect them by day.[3] Eagle pairs sometimes hunt troops of monkey cooperatively, with one bird perching nearby to distract the primates, allowing the other to swoop in from behind, hopefully unnoticed, for the kill.[3][28] Since the native macaque is often around the same size as the eagle itself, at approximately 9 kg (20 lb) in adult males, it is a potentially hazardous prey, and eagles have been reported to suffer broken leg due from a fall after struggling and fell along with a large male monkey.[30]

Reproduction

The complete breeding cycle of the Philippine Eagle lasts two years. The female matures sexually at five years of age and the male at seven. Like most eagles, the Philippine Eagle is monogamous. Once paired, a couple remains together for the rest of their lives.[6] If one dies, the remaining eagle often searches for a new mate to replace the one lost.[29]

The beginning of courtship is signaled by nest-building, and the eagle remaining near its nest. Aerial displays also play a major role in the courtship. These displays include paired soaring over a nesting territory, the male chasing the female in a diagonal dive, and mutual talon presentation, where the male presents his talons to the female's back and she flips over in midair to present her own talons. Advertisement displays coupled with loud calling have also been reported. The willingness of an eagle to breed is displayed by the eagle bringing nesting materials to the bird's nest. Copulation follows and occurs repeatedly both on the nest and on nearby perches. The earliest courtship has been reported in July.[29]

Breeding season is in July; birds on different islands, most notably Mindanao and Luzon, begin breeding at different ends of this range.[6] The amount of rainfall and population of prey may also affect the breeding season.[6] The nest is normally built on an emergent dipterocarp, or any tall tree with an open crown, in primary or disturbed forest. The nests are lined with green leaves, and can be around 1.5 m (4.9 ft) across. The nesting location is around 30 m (98 ft) or even more above the ground.[7][28] As in many other large raptors, the eagle's nest resembles a huge platform made of sticks.[3][28] The eagle frequently reuses the same nesting site for several different chicks.[7] Eight to 10 days before the egg is ready to be laid, the female is afflicted with a condition known as egg lethargy. In this experience, the female does not eat, drinks lots of water, and holds her wings droopingly.[29] The female typically lays one egg in the late afternoon or at dusk, although occasionally two have been reported.[28][29] If an egg fails to hatch or the chick dies early, the parents will likely lay another egg the following year. Copulation may last a few days after the egg is laid to enable another egg to be laid should the first one fail. The egg is incubated for 58 to 68 days (typically 62 days) after being laid.[3] Both sexes participate in the incubation, but the female does the majority of incubating during the day and all of it at night.[29]

Both sexes help feed the newly hatched eaglet. Additionally, the parents have been observed taking turns shielding the eaglet from the sun and rain until it is seven weeks old.[29] The young eaglet fledges after four or five months.[28] The earliest an eagle has been observed making a kill is 304 days after hatching.[29] Both parents take care of the eaglet for a total of 20 months and, unless the previous nesting attempt had failed, the eagles can breed only in alternate years.[3][6] The Philippine Eagle rivals two other large tropical eagles, namely the Crowned Eagle and Harpy Eagle, for having the longest breeding cycle of any bird of prey.[3][32] Even nests have no predators other than humans, as even known nest predators such as palm civets and macaques (being prey species) are likely to actively avoid any area with regular eagle activity.[33]

Conservation

.jpg)

In 2010, the IUCN and BirdLife International listed this species as critically endangered.[1][14] The International Union for the Conservation of Nature believes between 180 and 500 Philippine Eagles survive in the Philippines.[6] They are threatened primarily by deforestation through logging and expanding agriculture. Old-growth forest is being lost at a high rate, and most of the forest in the lowlands is owned by logging companies.[7] Mining, pollution, exposure to pesticides that affect breeding, and poaching are also major threats.[5][6] Additionally, they are occasionally caught in traps laid by local people for deer. Though this is no longer a major problem, the eagle's numbers were also reduced by being captured for zoos.[6]

The diminishing numbers of the Philippine Eagle were first brought to international attention in 1965 by the noted Filipino ornithologist Dioscoro S. Rabor, and the director of the Parks and Wildlife Office, Jesus A. Alvarez.[34][35][36] Charles Lindbergh, best known for crossing the Atlantic alone and without stopping in 1927, was fascinated by this eagle. As a representative of the World Wildlife Fund, Lindbergh traveled to the Philippines several times between 1969 and 1972, where he helped persuade the government to protect the eagle. In 1969, the Monkey-eating Eagle Conservation Program was started to help preserve this species. In 1992, the first Philippine Eagles were born in captivity through artificial insemination; however, not until 1999 was the first naturally bred eaglet hatched. The first captive-bred bird to be released in the wild, Kabayan, was released in 2004 on Mindanao; however, he was accidentally electrocuted in January 2005. Another eagle, Kagsabua, was released March 6, 2008, but was shot and eaten by a farmer.[6] Killing this critically endangered species is punishable under Philippine law by 12 years in jail and heavy fines.[5]

Its numbers have slowly dwindled over the decades to the current population of 180 to 500 eagles. A series of floods and mud slides, caused by deforestation, further devastated the remaining population. The Philippine Eagle may soon no longer be found in the wild, unless direct intervention is taken. The Philippine Eagle Foundation of Davao City, Mindanao is one organization dedicated to the protection and conservation of the Philippine Eagle and its forest habitat. The Philippine Eagle Foundation has successfully bred Philippine Eagles in captivity for over a decade and conducted the first experimental release of a captive-bred eagle to the wild. The foundation has 35 eagles at its center, of which 18 were bred in captivity.[6] Ongoing research on behavior, ecology, and population dynamics is also underway. In recent years, protected lands have been established specifically for this species, such as the 700 km2 (170,000 acres) of Cabuaya Forest and the 37.2 square kilometers (9,200 acres) of Taft Forest Wildlife Sanctuary on Samar.[37] However, a large proportion of the population is found on unprotected land.[6]

Relationship with humans

The Philippine Eagle was officially declared the national bird of the Philippines on 4 July 1995 by President Fidel V. Ramos under Proclamation No. 615.[38] This eagle, because of its size and rarity, is also a highly desired bird for birdwatchers.[28]

The Philippine Eagle has also featured on at least 12 stamps from the Philippines, with dates ranging from 1967 to 2007. It was also depicted on the 50-centavo coins minted from 1981 to 1994.

Historically, about 50 Philippine Eagles have been kept in zoos in Europe (England, Germany, Belgium, Italy and France), the United States, and Japan.[39] The first was a female that arrived in London Zoo in August 1909[39] and died there in February 1910.[40] The majority arrived in zoos between 1947 and 1965.[39] The last outside the Philippines died in 1988 in the Antwerp Zoo, where it had lived since 1964 (except for a period at the Planckendael Zoo in Belgium).[39] The first captive breeding was only achieved in 1992 at the facility of the Philippine Eagle Foundation in Davao City, Mindanao, the Philippines, which has bred it several times since then.[6][41]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pithecophaga jefferyi. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Pithecophaga jefferyi |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 BirdLife International (2013). "Pithecophaga jefferyi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Tabaranza, Blas R., Jr. (2005-01-17). "The largest eagle in the world". Haribon Foundation. Retrieved 2012-09-23.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D. (2001). Raptors of the World. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 717–19. ISBN 0-7136-8026-1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kennedy, R. S., Gonzales, P. C.; Dickinson, E. C.; Miranda, H. C., Jr. and Fisher, T. H. (2000). A Guide to the Birds of the Philippines. Oxford University Press, New York. ISBN 0-19-854669-6

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Farmer arrested for killing, eating rare Philippines eagle: officials". AFP. 2008-07-18. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 Rare Birds Yearbook 2009. England: MagDig Media Lmtd. 2008. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-0-9552607-5-9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Rare Birds Yearbook 2008. England: MagDig Media Lmtd. 2007. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-9552607-3-5.

- ↑ Collar, N.J. (December 24, 1996). "The Philippine Eagle: one hundred years of solitude". Oriental Bird Club Bulletin.

- ↑ Doctolero, Heidi; Pilar Saldajeno and Mary Ann Leones (2007-04-29). "Philippine biodiversity, a world’s showcase". Manila Times. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Clements, James F (2007). The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World Sixth Edition. Ithaca, NY: Comstock Publishing Associates. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8014-4501-9.

- ↑ Almario, Ani Rosa S. (2007). 101 Filipino Icons. Adarna House Publishing Inc. p. 112. ISBN 971-508-302-1.

- ↑ Shufeldt, RW (1919). "Osteological and other notes on the monkey-eating eagle of the Philippines, Pithecophaga jefferyi Grant". Philippine Journal of Science 15: 31–58.

- ↑ Lerner, Heather R.L. & David P. Mindell (2005). "Phylogeny of eagles, Old World vultures, and other Accipitridae based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA" (pdf). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 37 (2): 327–346. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.010. PMID 15925523.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 "Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi )". BirdLife International. 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2000). Threatened Birds of the World. Lynx Edictions, Barcelona. ISBN 0-946888-39-6

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Clark, W. S. (1994). Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi). pp. 192 in: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J. eds. (1994). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Lynx Edictions, Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-15-6

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Gamauf, A., Preleuthner, M. and Winkler, H. (1998). "Philippine Birds of Prey: Interrelations among habitat, morphology and behavior". The Auk 115 (3): 713–726. doi:10.2307/4089419.

- ↑ O'Connor, R. J. (1984). The Growth and Development of Birds. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester. ISBN 0-471-90345-0

- ↑ Arent, L. A. (2007). Raptors in Captivity. Hancock House, Washington. ISBN 978-0-88839-613-6

- ↑ Mearns, EA (1905). "Note on a specimen of Pithecophaga jefferyi Ogilvie-Grant". Proc. Biol. Soc. Wash. 18: 76–77.

- ↑ Seth-Smith, D (1910). "On the Monkey-eating Eagle of the Philippines (Pithecophaga jefferyi)". Ibis 52 (2): 285–290. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1910.tb07905.x.

- ↑ CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ↑ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ↑ Dupont, John Eleuthere (1971). Philippine Birds, p. 47. Delaware Museum of Natural History

- ↑ Kennedy, RS (1977). "Notes on the biology and population status of the Monkey-eating Eagle of the Philippines" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin 89 (1): 1–20.

- ↑ http://www.pia.gov.ph/news/index.php?article=1151371448685

- ↑ Bueser, GL; Bueser, K. G.; Afan, D.S.; Salvador, D.I.; Grier, J.W.; Kennedy, R.S. and Miranda, H.C., Jr. (2003). "Distribution and nesting density of the Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi on Mindanao Island, Philippines: what do we know after 100 years?" (PDF). Ibis 145: 130–135. doi:10.1046/j.1474-919X.2003.00131.x.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 28.7 28.8 28.9 Chandler, David; Couzens, Dominic (2008). 100 Birds to See Before You Die. London: Carleton Books. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-84442-019-3.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 29.8 29.9 29.10 29.11 Jamora, Jon. "Philippine Eagle Biology and Ecology". Philippine Eagle Foundation. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi. birdbase.hokkaido-ies.go.jp

- ↑ BirdLife International (2001). "Philippine Eagle: Pithecophaga jefferyi", pp. 647–648 in Threatened Birds of Asia. Accessed July 1, 2011

- ↑ Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World by Leslie Brown & Dean Amadon. The Wellfleet Press (1986), ISBN 978-1555214722.

- ↑ Delacour, J., E. Mayr. 1946. Birds of the Philippines. New York: The MacMillan Company.

- ↑ Kennedy, Robert S. and Miranda, Hector C., Jr.; Miranda (1998). "In Memoriam: Dioscoro S. Rabor". The Auk 115 (1): 204–205. doi:10.2307/4089125.

- ↑ "Focusing on the Philippine Eagle for the conservation of nature". The Philippine Eagle Foundation.

- ↑ "Philippine Eagle: Lost in Vanishing Forests". Philippine Network of Environmental Journalists, Inc. June 10, 2011.

- ↑ Labro, Vicente (2007-07-19). "2 Philippine eagles spotted in Leyte forest". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2001). "Philippine Eagle: Pithecophaga jefferyi", p. 661 in Threatened Birds of Asia. Accessed April 28, 2010

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Weigl, R, & Jones, M. L. (2000). The Philippine Eagle in captivity outside the Philippines, 1909–1988. International Zoo News vol. 47/8 (305)

- ↑ Davidson, M. E. McLellan (1934). "Specimens of the Philippine Monkey-Eating Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi)". The Auk 51 (3): 338–342. doi:10.2307/4077661.

- ↑ Philippine Eagle Working Group (1996). Integrated Conservation Plan For The Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi).

External links

- Philippine Eagle Foundation. A foundation devoted to saving the Philippine Eagle.

- Animal Diversity Web – Pithecophaga jefferyi

- National Geographic Magazine – "The Lord of the Forest"

- Bringing Back Ol' Blue Eyes – article on Philippine Eagle Foundation work on Mindanao

- Video of Philippine eagle hunting flying lemurs

- Photos of the Philippine Eagle by Klaus Nigge

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||