Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetics may be simply defined as what the body does to the drug, as opposed to pharmacodynamics which may be defined as what the drug does to the body.

Pharmacokinetics, sometimes abbreviated as PK, (from Ancient Greek pharmakon "drug" and kinetikos "to do with motion"; see chemical kinetics) is a branch of pharmacology dedicated to the determination of the fate of substances administered externally to a living organism. The substances of interest include pharmaceutical agents, hormones, nutrients, and toxins. It attempts to discover the fate of a drug from the moment that it is administered up to the point at which it is completely eliminated from the body. Pharmacokinetics describes how the body affects a specific drug after administration through the mechanisms of absorption and distribution, as well as the chemical changes of the substance in the body (e.g. by metabolic enzymes such as cytochrome P450 or glucuronosyltransferase enzymes), and the effects and routes of excretion of the metabolites of the drug.[1] Pharmacokinetic properties of drugs may be affected by elements such as the site of administration and the dose of administered drug. These may affect the absorption rate.[2] Pharmacokinetics is often studied in conjunction with pharmacodynamics, the study of a drug's pharmacological effect on the body.

A number of different models have been developed in order to simplify conceptualization of the many processes that take place in the interaction between an organism and a drug. One of these models, the multi-compartment model, gives the best approximation to reality, however, the complexity involved in using this type of model means that monocompartmental models and above all two compartmental models are the most frequently used. The various compartments that the model is divided into is commonly referred to as the ADME scheme (also referred to as LADME if liberation is included as a separate step from absorption):

- Liberation - the process of release of a drug from the pharmaceutical formulation.[3][4] See also IVIVC.

- Absorption - the process of a substance entering the blood circulation.

- Distribution - the dispersion or dissemination of substances throughout the fluids and tissues of the body.

- Metabolization (or biotransformation, or inactivation) – the recognition by the organism that a foreign substance is present and the irreversible transformation of parent compounds into daughter metabolites.

- Excretion - the removal of the substances from the body. In rare cases, some drugs irreversibly accumulate in body tissue.

The two phases of metabolism and excretion can also be grouped together under the title elimination. The study of these distinct phases involves the use and manipulation of basic concepts in order to understand the process dynamics. For this reason in order to fully comprehend the kinetics of a drug it is necessary to have detailed knowledge of a number of factors such as: the properties of the substances that act as excipients, the characteristics of the appropriate biological membranes and the way that substances can cross them, or the characteristics of the enzyme reactions that inactivate the drug.

All these concepts can be represented through mathematical formulas that have a corresponding graphical representation. The use of these models allows an understanding of the characteristics of a molecule, as well as how a particular drug will behave given information regarding some of its basic characteristics. Such as its acid dissociation constant (pKa), bioavailability and solubility, absorption capacity and distribution in the organism.

The model outputs for a drug can be used in industry (for example, in calculating bioequivalence when designing generic drugs) or in the clinical application of pharmacokinetic concepts. Clinical pharmacokinetics provides many performance guidelines for effective and efficient use of drugs for human-health professionals and in veterinary medicine.

Branch of pharmacology concerned with the uptake of drugs by the body,

the biotransformation of the drugs and their metabolites in the tissues,

and the elimination of the drugs and their metabolites from the body over

a period of time.

Note 1: Modified from ref.[5]

Note 2: Pharmacokinetics also includes the distribution of bioactive

substances within the various compartments present in an animal or human

body, especially high-molar-mass polymers that cannot cross endothelial

or epithelial physiological barriers.[6]

Metrics

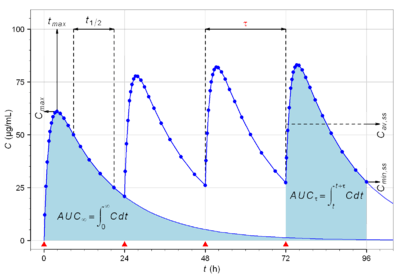

The following are the most commonly measured pharmacokinetic metrics:[7]

| Characteristic | Description | Example value | Symbol | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose | Amount of drug administered. | 500 mg |  | Design parameter |

| Dosing interval | Time between drug dose administrations. | 24 h |  | Design parameter |

| Cmax | The peak plasma concentration of a drug after administration. | 60.9 mg/L |  | Direct measurement |

| tmax | Time to reach Cmax. | 3.9 h |  | Direct measurement |

| Cmin | The lowest (trough) concentration that a drug reaches before the next dose is administered. | 27.7 mg/L |  | Direct measurement |

| Volume of distribution | The apparent volume in which a drug is distributed (i.e., the parameter relating drug concentration to drug amount in the body). | 6.0 L |  |  |

| Concentration | Amount of drug in a given volume of plasma. | 83.3 mg/L |  |  |

| Elimination half-life | The time required for the concentration of the drug to reach half of its original value. | 12 h |  |  |

| Elimination rate constant | The rate at which a drug is removed from the body. | 0.0578 h−1 |  |  |

| Infusion rate | Rate of infusion required to balance elimination. | 50 mg/h |  |  |

| Area under the curve | The integral of the concentration-time curve (after a single dose or in steady state). | 1,320 mg/L·h |  |  |

|  | |||

| Clearance | The volume of plasma cleared of the drug per unit time. | 0.38 L/h |  |  |

| Bioavailability | The systemically available fraction of a drug. | 0.8 |  |  |

| Fluctuation | Peak trough fluctuation within one dosing interval at steady state | 41.8 % |  |  where  |

In pharmacokinetics, steady state refers to the situation where the overall intake of a drug is fairly in dynamic equilibrium with its elimination. In practice, it is generally considered that steady state is reached when a time of 4 to 5 times the half-life for a drug after regular dosing is started.

The following graph depicts a typical time course of drug plasma concentration and illustrates main pharmacokinetic metrics:

Pharmacokinetic models

Pharmacokinetic modelling is performed by noncompartmental or compartmental methods. Noncompartmental methods estimate the exposure to a drug by estimating the area under the curve of a concentration-time graph. Compartmental methods estimate the concentration-time graph using kinetic models. Noncompartmental methods are often more versatile in that they do not assume any specific compartmental model and produce accurate results also acceptable for bioequivalence studies. The final outcome of the transformations that a drug undergoes in an organism and the rules that determine this fate depend on a number of interrelated factors. A number of functional models have been developed in order to simplify the study of pharmacokinetics. These models are based on a consideration of an organism as a number of related compartments. The simplest idea is to think of an organism as only one homogenous compartment. This monocompartimental model presupposes that blood plasma concentrations of the drug are a true reflection of the drug’s concentration in other fluids or tissues and that the elimination of the drug is directly proportional to the drug’s concentration in the organism (first order kinetics).

However, these models do not always truly reflect the real situation within an organism. For example, not all body tissues have the same blood supply, so the distribution of the drug will be slower in these tissues than in others with a better blood supply. In addition, there are some tissues (such as the brain tissue) that present a real barrier to the distribution of drugs, they can be breached with greater or lesser ease depending of the drug’s characteristics. If these relative conditions for the different tissue types are considered along with the rate of elimination, the organism can be considered to be acting like two compartments: one that we can call the central compartment that has a more rapid distribution, comprising organs and systems with a well-developed blood supply; and a peripheral compartment made up of organs with a lower blood flow. Other tissues, such as the brain, can occupy a variable position depending on a drug’s ability to cross the barrier that separates the organ from the blood supply.

This two compartment model will vary depending on which compartment elimination occurs in. The most common situation is that elimination occurs in the central compartment as the liver and kidneys are organs with a good blood supply. However, in some situations it may be that elimination occurs in the peripheral compartment or even in both. This can mean that there are three possible variations in the two compartment model, which still do not cover all possibilities.[8]

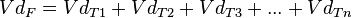

This model may not be applicable in situations where some of the enzymes responsible for metabolizing the drug become saturated, or where an active elimination mechanism is present that is independent of the drug's plasma concentration. In the real world each tissue will have its own distribution characteristics and none of them will be strictly linear. If we label the drug’s volume of distribution within the organism VdF and its volume of distribution in a tissue VdT the former will be described by an equation that takes into account all the tissues that act in different ways, that is:

This represents the multi-compartment model with a number of curves that express complicated equations in order to obtain an overall curve. A number of computer programmes have been developed to plot these equations.[8] However complicated and precise this model may be it still does not truly represent reality despite the effort involved in obtaining various distribution values for a drug. This is because the concept of distribution volume is a relative concept that is not a true reflection of reality. The choice of model therefore comes down to deciding which one offers the lowest margin of error for the type of drug involved.

Noncompartmental analysis

Noncompartmental PK analysis is highly dependent on estimation of total drug exposure. Total drug exposure is most often estimated by area under the curve (AUC) methods, with the trapezoidal rule (numerical integration) the most common method. Due to the dependence on the length of 'x' in the trapezoidal rule, the area estimation is highly dependent on the blood/plasma sampling schedule. That is, the closer time points are, the closer the trapezoids reflect the actual shape of the concentration-time curve.

Compartmental analysis

Compartmental PK analysis uses kinetic models to describe and predict the concentration-time curve. PK compartmental models are often similar to kinetic models used in other scientific disciplines such as chemical kinetics and thermodynamics. The advantage of compartmental over some noncompartmental analyses is the ability to predict the concentration at any time. The disadvantage is the difficulty in developing and validating the proper model. Compartment-free modelling based on curve stripping does not suffer this limitation. The simplest PK compartmental model is the one-compartmental PK model with IV bolus administration and first-order elimination. The most complex PK models (called PBPK models) rely on the use of physiological information to ease development and validation.

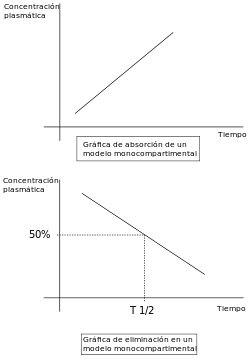

Single-compartment model

Linear pharmacokinetics is so-called because the graph of the relationship between the various factors involved (( dose, blood plasma concentrations, elimination, etc.) gives a straight line or an approximation to one. For drugs to be effective they need to be able to move rapidly from blood plasma to other body fluids and tissues.

The change in concentration over time can be expressed as C=Cinitial*E^(-kelt)

Multi-compartmental models

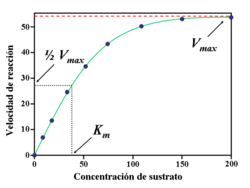

The graph for the non-linear relationship between the various factors is represented by a curve, the relationships between the factors can then be found by calculating the dimensions of different areas under the curve. The models used in 'non linear pharmacokinetics are largely based on Michaelis-Menten kinetics. A reaction’s factors of non linearity include the following:

- Multiphasic absorption : Drugs injected intravenously are removed from the plasma through two primary mechanisms: (1) Distribution to body tissues and (2) metabolism + excretion of the drugs. The resulting decrease of the drug's plasma concentration follows a biphasic pattern (see figure).

Plasma drug concentration vs time after an IV dose

Plasma drug concentration vs time after an IV dose- Alpha phase: An initial phase of rapid decrease in plasma concentration. The decrease is primarily attributed to drug distribution from the central compartment (circulation) into the peripheral compartments (body tissues). This phase ends when a pseudo-equilibrium of drug concentration is established between the central and peripheral compartments.

- Beta phase: A phase of gradual decrease in plasma concentration after the alpha phase. The decrease is primarily attributed to drug metabolism and excretion.[9]

- Additional phases (gamma, delta, etc.) are sometimes seen.[10]

- A drug’s characteristics make a clear distinction between tissues with high and low blood flow.

- Enzymatic saturation: When the dose of a drug whose elimination depends on biotransformation is increased above a certain threshold the enzymes responsible for its metabolism become saturated. The drug’s plasma concentration will then increase disproportionately and its elimination will no longer be constant.

- Induction or enzymatic inhibition: Some drugs have the capacity to inhibit or stimulate their own metabolism, in negative or positive feedback reactions. As occurs with fluvoxamine, fluoxetine and phenytoin. As larger doses of these pharmaceuticals are administered the plasma concentrations of the unmetabolized drug increases and the elimination half-life increases. It is therefore necessary to adjust the dose or other treatment parameters when a high dosage is required.

- The kidneys can also establish active elimination mechanisms for some drugs, independent of plasma concentrations.

It can therefore be seen that non-linearity can occur because of reasons that affect the whole of the pharmacokinetic sequence: absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination.

Bioavailability

At a practical level, a drug’s bioavailability can be defined as the proportion of the drug that reaches its site of action. From this perspective the intravenous administration of a drug provides the greatest possible bioavailability, and this method is considered to yield a bioavailability of 1 (or 100%). Bioavailability of other delivery methods is compared with that of intravenous injection («absolute bioavailability») or to a standard value related to other delivery methods in a particular study («relative bioavailability»).

![B_{A}={\frac {[ABC]_{P}.D_{{IV}}}{[ABC]_{{IV}}.D_{P}}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/5/c/a/3/5ca3c5293ac76c5cc118262203196262.png)

![{\mathit B}_{R}={\frac {[ABC]_{{A}}.dose_{{B}}}{[ABC]_{{B}}.dose_{{A}}}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/4/5/9/3/4593e75474bbd3859a4776d08f08d7fc.png)

Once a drug’s bioavailability has been established it is possible to calculate the changes that need to be made to its dosage in order to reach the required blood plasma levels. Bioavailability is therefore a mathematical factor for each individual drug that influences the administered dose. It is possible to calculate the amount of a drug in the blood plasma that has a real potential to bring about its effect using the formula:  ; where De is the effective dose, B bioavailability and Da the administered dose.

; where De is the effective dose, B bioavailability and Da the administered dose.

Therefore, if a drug has a bioavailability of 0.8 (or 80%) and it is administered in a dose of 100 mg, the equation will demonstrate the following:

That is the 100 mg administered represents a blood plasma concentration of 80 mg that has the capacity to have a pharmaceutical effect.

This concept depends on a series of factors inherent to each drug, such as:[11]

- Pharmaceutical form

- Chemical form

- Route of administration

- Stability

- Metabolism

These concepts, which are discussed in detail in their respective titled articles, can be mathematically quantified and integrated to obtain an overall mathematical equation:

where Q is the drug’s purity.[11]

where  is the drug’s rate of administration and

is the drug’s rate of administration and  is the rate at which the absorbed drug reaches the circulatory system.

is the rate at which the absorbed drug reaches the circulatory system.

Finally, using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation, and knowing the drug’s  (pH at which there is an equilibrium between its ionized and non ionized molecules), it is possible to calculate the non ionized concentration of the drug and therefore the concentration that will be subject to absorption:

(pH at which there is an equilibrium between its ionized and non ionized molecules), it is possible to calculate the non ionized concentration of the drug and therefore the concentration that will be subject to absorption:

When two drugs have the same bioavailability, they are said to be biological equivalents or bioequivalents. This concept of bioequivalence is important because it is currently used as a yardstick in the authorization of generic drugs in many countries .

LADME

A number of phases occur once the drug enters into contact with the organism, these are described using the acronym LADME:

- Liberation of the active substance from the delivery system,

- Absorption of the active substance by the organism,

- Distribution through the blood plasma and different body tissues,

- Metabolism that is, inactivation of the xenobiotic substance, and finally

- Excretion or elimination of the substance or the products of its metabolism.

Some textbooks combine the first two phases as the drug is often administered in an active form, which means that there is no liberation phase. Others include a phase that combines distribution, metabolization and excretion into a «disposition phase». Other authors include the drug’s toxicological aspect in what is known as ADME-Tox or ADMET.

Each of the phases is subject to physico-chemical interactions between a drug and an organism, which can be expressed mathematically. Pharmacokinetics is therefore based on mathematical equations that allow the prediction of a drug’s behaviour and which place great emphasis on the relationships between drug plasma concentrations and the time elapsed since the drug’s administration.

Analysis

Bioanalytical methods

Bioanalytical methods are necessary to construct a concentration-time profile. Chemical techniques are employed to measure the concentration of drugs in biological matrix, most often plasma. Proper bioanalytical methods should be selective and sensitive. For example microscale thermophoresis can be used to quantify how the biological matrix/liquid affects the affinity of a drug to its target.[12][13]

Mass spectrometry

Pharmacokinetics is often studied using mass spectrometry because of the complex nature of the matrix (often plasma or urine) and the need for high sensitivity to observe concentrations after a low dose and a long time period. The most common instrumentation used in this application is LC-MS with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Tandem mass spectrometry is usually employed for added specificity. Standard curves and internal standards are used for quantitation of usually a single pharmaceutical in the samples. The samples represent different time points as a pharmaceutical is administered and then metabolized or cleared from the body. Blank samples taken before administration are important in determining background and insuring data integrity with such complex sample matrices. Much attention is paid to the linearity of the standard curve; however it is not uncommon to use curve fitting with more complex functions such as quadratics since the response of most mass spectrometers is less than linear across large concentration ranges.[14][15][16]

There is currently considerable interest in the use of very high sensitivity mass spectrometry for microdosing studies, which are seen as a promising alternative to animal experimentation.[17]

Population pharmacokinetics

Population pharmacokinetics is the study of the sources and correlates of variability in drug concentrations among individuals who are the target patient population receiving clinically relevant doses of a drug of interest.[18][19][20] Certain patient demographic, pathophysiological, and therapeutical features, such as body weight, excretory and metabolic functions, and the presence of other therapies, can regularly alter dose-concentration relationships. For example, steady-state concentrations of drugs eliminated mostly by the kidney are usually greater in patients suffering from renal failure than they are in patients with normal renal function receiving the same drug dosage. Population pharmacokinetics seeks to identify the measurable pathophysiologic factors that cause changes in the dose-concentration relationship and the extent of these changes so that, if such changes are associated with clinically significant shifts in the therapeutic index, dosage can be appropriately modified. An advantage of population pharmacokinetic modelling is its ability to analyse sparse data sets (sometimes only one concentration measurement per patient is available).

Software packages used in population pharmacokinetics modelling include NONMEM, which was developed at the UCSF and newer packages which incorporate GUIs like Monolix as well as graphical model building tools; Phoenix NLME.

Clinical pharmacokinetics

Clinical pharmacokinetics (arising from the clinical use of population pharmacokinetics) is the direct application to a therapeutic situation of knowledge regarding a drug’s pharmacokinetics and the characteristics of a population that a patient belongs to (or can be ascribed to).

An example is the relaunch of the use of cyclosporine as an immunosuppressor to facilitate organ transplant. The drug's therapeutic properties were initially demonstrated, but it was almost never used after it was found to cause nephrotoxicity in a number of patients.[21] However, it was then realized that it was possible to individualize a patient’s dose of cyclosporine by analysing the patients plasmatic concentrations (pharmacokinetic monitoring). This practice has allowed this drug to be used again and has facilitated a great number of organ transplants.

Clinical monitoring is usually carried out by determination of plasma concentrations as this data is usually the easiest to obtain and the most reliable. The main reasons for determining a drug’s plasma concentration include:[22]

- Narrow therapeutic range (difference between toxic and therapeutic concentrations)

- High toxicity

- High risk to life.

Drugs where pharmacokinetic monitoring is recommended include:

|

|

|

|

|

|

* Antiviral (HIV) medication |

|

Ecotoxicology

Ecotoxicology is the study of toxic effects on a wide range of organisms and includes considerations of toxicokinetics and toxicodynamics.[23][24]

Software

Academic licenses are available for most commercial programs.

Noncompartmental

- Freeware: bear and PK for R

- Commercial: EquivTest, Kinetica, MATLAB/SimBiology, Phoenix/WinNonlin, PK Solutions.

Compartment based

- Freeware: ADAPT, Boomer (GUI), SBPKPD.org (Systems Biology Driven Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics), WinSAAM, PKfit for R.

- Commercial: Imalytics, Kinetica, MATLAB/SimBiology, Phoenix/WinNonlin, PK Solutions, PottersWheel, SAAM II.

Physiologically based

- Freeware: MCSim

- Commercial: acslX, Cloe PK, GastroPlus, MATLAB/SimBiology, PK-Sim, Simcyp, Entelos PhysioLab Phoenix/WinNonlin, ADME Workbench.

Population PK

- Freeware: WinBUGS, ADAPT, Boomer, PKBugs, Pmetrics for R.

- Commercial: Kinetica, MATLAB/SimBiology, Monolix, NONMEM, Phoenix/NLME, PopKinetics for SAAM II, USC*PACK.

Simulation

All model based software above.

- Freeware: Berkeley Madonna, MEGen.

Educational centres

Global centres with the highest profiles for providing in-depth training include the Universities of Buffalo, Florida, Gothenburg, Leiden, Otago, San Francisco, Tokyo, Uppsala, Washington, Manchester and University of Sheffield.[25]

See also

- Blood alcohol concentration

- Biological half-life

- Bioavailability

- Enzyme kinetics

- Pharmacodynamics

- Bioequivalence

- Generic drugs

- Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modelling

- Plateau Principle

- Toxicokinetics

References

- ↑ Pharmacokinetics. (2006). In Mosby's Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, & Health Professions. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences. Retrieved December 11, 2008, from http://www.credoreference.com/entry/6686418

- ↑ Kathleen Knights; Bronwen Bryant (2002). Pharmacology for Health Professionals. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 0-7295-3664-5.

- ↑ Koch HP, Ritschel WA (1986). "Liberation". Synopsis der Biopharmazie und Pharmakokinetik (in German). Landsberg, München: Ecomed. pp. 99–131. ISBN 3-609-64970-4.

- ↑ Ruiz-Garcia A, Bermejo M, Moss A, Casabo VG (February 2008). "Pharmacokinetics in drug discovery". J Pharm Sci 97 (2): 654–90. doi:10.1002/jps.21009. PMID 17630642.

- ↑ Alan D. MacNaught, Andrew R. Wilkinson, ed. (1997). Compendium of Chemical Terminology: IUPAC Recommendations (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0865426848.

- ↑ "Terminology for biorelated polymers and applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012)". Pure and Applied Chemistry 84 (2): 377–410. 2012. doi:10.1351/PAC-REC-10-12-04.

- ↑ AGAH working group PHARMACOKINETICS (2004-02-16). "Collection of terms, symbols, equations, and explanations of common pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters and some statistical functions" (PDF). Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Angewandte Humanpharmakologie (AGAH) (Association for Applied Human Pharmacology). Retrieved 2011-04-04.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Milo Gibaldi, Donald Perrier. FarmacocinéticaReverté 1982 pages 1-10. ISBN 84-291-5535-X, 9788429155358

- ↑ Gill SC, Moon-Mcdermott L, Hunt TL, Deresinski S, Blaschke T, Sandhaus RA (Sep 1999). "Phase I Pharmacokinetics of Liposomal Amikacin (MiKasome) in Human Subjects: Dose Dependence and Urinary Clearance". Abstr Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39: 33 (abstract no. 1195).

- ↑ Weiner, Daniel; Johan Gabrielsson (2000). "PK24 - Non-linear kinetics - flow II". Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data analysis: concepts and applications. Apotekarsocieteten. pp. 527–36. ISBN 91-86274-92-9.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Michael E. Winter, Mary Anne Koda-Kimple, Lloyd Y. Young, Emilio Pol Yanguas Farmacocinética clínica básica Ediciones Díaz de Santos, 1994 pgs. 8-14 ISBN 84-7978-147-5, 9788479781477 (in Spanish)

- ↑ Baaske P, Wienken CJ, Reineck P, Duhr S, Braun D (Feb 2010). "Optical Thermophoresis quantifies Buffer dependence of Aptamer Binding". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 (12): 1–5. doi:10.1002/anie.200903998. PMID 20186894. Lay summary – Phsyorg.com.

- ↑ Wienken CJ et al. (2010). "Protein-binding assays in biological liquids using microscale thermophoresis". Nature Communications 1 (7): 100. Bibcode:2010NatCo...1E.100W. doi:10.1038/ncomms1093. PMID 20981028.

- ↑ Hsieh Y, Korfmacher WA (June 2006). "Increasing speed and throughput when using HPLC-MS/MS systems for drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic screening". Current Drug Metabolism 7 (5): 479–89. doi:10.2174/138920006777697963. PMID 16787157.

- ↑ Covey TR, Lee ED, Henion JD (October 1986). "High-speed liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry for the determination of drugs in biological samples". Anal. Chem. 58 (12): 2453–60. doi:10.1021/ac00125a022. PMID 3789400.

- ↑ Covey TR, Crowther JB, Dewey EA, Henion JD (February 1985). "Thermospray liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry determination of drugs and their metabolites in biological fluids". Anal. Chem. 57 (2): 474–81. doi:10.1021/ac50001a036. PMID 3977076.

- ↑ Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) (December 2009). "ICH guideline M3(R2) on non-clinical safety studies for the conduct of human clinical trials and marketing authorisation for pharmaceuticals" (PDF). European Medicines Agency, Evaluation of Medicines for Human Use. Retrieved 4 May 2013. Unknown parameter

|reference=ignored (help) - ↑ Sheiner LB, Rosenberg B, Marathe VV (October 1977). "Estimation of population characteristics of pharmacokinetic parameters from routine clinical data". J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 5 (5): 445–79. doi:10.1007/BF01061728. PMID 925881.

- ↑ Sheiner LB, Beal S, Rosenberg B, Marathe VV (September 1979). "Forecasting individual pharmacokinetics". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 26 (3): 294–305. PMID 466923.

- ↑ Bonate PL (2005). "Recommended reading in population pharmacokinetic pharmacodynamics". AAPS J 7 (2): E363–73. doi:10.1208/aapsj070237. PMC 2750974. PMID 16353916.

- ↑ R. García del Moral, M. Andújar y F. O'Valle Mecanismos de nefrotoxicidad por ciclosporina A a nivel celular (in Spanish). NEFROLOGIA. Vol. XV. Supplement 1, 1995. Consulted 23 February 2008.

- ↑ Joaquín Herrera Carranza Manual de farmacia clínica y Atención Farmacéutica (in Spanish). Published by Elsevier España, 2003; page 159. ISBN 84-8174-658-4

- ↑ Jager T, Albert C, Preuss TG, Ashauer R (April 2011). "General unified threshold model of survival--a toxicokinetic-toxicodynamic framework for ecotoxicology". Environ. Sci. Technol. 45 (7): 2529–40. Bibcode:2011EnST...45.2529J. doi:10.1021/es103092a. PMID 21366215.

- ↑ Ashauer R. "Toxicokinetic-Toxicodynamic Models - Ecotoxicology and Models". Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Tucker GT (June 2012). "Research priorities in pharmacokinetics". Br J Clin Pharmacol 73 (6): 924–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04238.x. PMID 22360418.

Bibliography

- Alberts et al., Introducción a la Biología Celular, pág. 375-376, 2ª edición, Ed. Médica Panamericana

- Alberts et al., Biología Molecular de la célula, pág. 595, 4ª edición, Ed. Omega

- Armijo JA. 2003. Farmacocinética: Absorción, Distribución y Eliminación de los Fármacos. En: Flórez J, Armijo JA, Mediavilla A, Farmacología Humana, 4ta edición. Masson. Barcelona. pp: 51-79.

- Balani SK, Miwa GT, Gan LS, Wu JT, Lee FW., Strategy of utilizing in vitro and in vivo ADME tools for lead optimization and drug candidate selection, Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5(11):1033-8.

- Beal, S.; Sheiner L.B. "The NONMEM System". The American Statistician 34: 118–9. (1980). doi:10.2307/2684123.

- Cooper, La célula, pág 470-471, 2ª edición, Ed. Marbán

- Covey TR, Lee ED, Henion JD "High-speed liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry for the determination of drugs in biological samples". Anal. Chem. 58: 2453–60. (October 1986). doi:10.1021/ac00125a022. PMID 3789400.

- Covey TR, JB Crowther, EA Dewey, JD Henion "Thermospray liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry determination of drugs and their metabolites in biological fluids". Anal. Chem. 57 (2): 474–81. (February 1985). doi:10.1021/ac50001a036. PMID 3977076.

- Danielson P (2002). "The cytochrome P450 superfamily: biochemistry, evolution and drug metabolism in humans". Curr Drug Metab 3 (6): 561-97. PMID 12369887.

- Davies K (1995). "Oxidative stress: the paradox of aerobic life". Biochem Soc Symp 61: 1-31. PMID 8660387.

- Devlin, T. M. 2004. Bioquímica, 4ª edición. Reverté, Barcelona. ISBN 84-291-7208-4

- Galvão T, Mohn W, de Lorenzo V (2005). "Exploring the microbial biodegradation and biotransformation gene pool". Trends Biotechnol 23 (10): 497-506. PMID 16125262.

- Hsieh Y, Korfmacher WA "Increasing speed and throughput when using HPLC-MS/MS systems for drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic screening". Current Drug Metabolism 7 (5): 479–89.(June 2006). PMID 16787157. Disponible en [http://www.bentham-direct.org/pages/content.php?CDM/2006/00000007/00000005/0004F.SGM.]

- Janssen D, Dinkla I, Poelarends G, Terpstra P (2005). "Bacterial degradation of xenobiotic compounds: evolution and distribution of novel enzyme activities". Environ Microbiol 7 (12): 1868-82. PMID 16309386.

- Kathleen Knights; Bronwen Bryant (2002). Pharmacology for Health Professionals. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 0-7295-3664-5.

- King C, Rios G, Green M, Tephly T (2000). "UDP-glucuronosyltransferases". Curr Drug Metab 1 (2): 143-61. PMID 11465080.

- Malcolm Rowland, Thomas N. Tozer. "Farmacocinética clínica: Conceptos y Aplicaciones"

- Pharmacokinetics. (2006). En Mosby's Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, & Health Professions. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences. Disponible en Última visita 11, diciembre de 2008,

- Sheehan D, Meade G, Foley V, Dowd C (2001). "Structure, function and evolution of glutathione transferases: implications for classification of non-mammalian members of an ancient enzyme superfamily". Biochem J 360 (Pt 1): 1-16. PMID 11695986.

- Sheiner, L.B.; Beal, S.L., Rosenberg, B. Marathe, V.V. "Forecasting Individual Pharmacokinetics". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 26: 294–305. (1979). PMID 466923.

- Sheiner, L.B.; Rosenberg, B., Marathe, V.V. "Estimation of Population Characteristics of Pharmacokinetic Parameters from Routine Clinical Data". J. Pharmacokin. Biopharm. 5: 445–79. 1.997 doi:10.1007/BF01061728.

- Sies H (1997). "Oxidative stress: oxidants and antioxidants". Exp Physiol 82 (2): 291-5. PMID 9129943.

- Singh SS., Preclinical pharmacokinetics: an approach towards safer and efficacious drugs, Curr Drug Metab. 2006 Feb;7(2):165-82.

- Testa B, Krämer S (2006). "The biochemistry of drug metabolism--an introduction: part 1. Principles and overview". Chem Biodivers 3 (10): 1053-101. PMID 17193224.

- Tetko IV, Bruneau P, Mewes HW, Rohrer DC, Poda GI., Can we estimate the accuracy of ADME-Tox predictions?, Drug Discov Today. 2006 Aug;11(15-16):700-7, pre-print.

- Tu B, Weissman J (2004). "Oxidative protein folding in eukaryotes: mechanisms and consequences". J Cell Biol 164 (3): 341-6. PMID 14757749.

- Vertuani S, Angusti A, Manfredini S (2004). "The antioxidants and pro-antioxidants network: an overview". Curr Pharm Des 10 (14): 1677-94. PMID 15134565.

External links

- Pharmacokinetic Two-Compartment Model from Wolfram Demonstrations Project (requires free download of CDF Player)

- http://vam.anest.ufl.edu/demos/onecompbolus.html

- http://www.biokinetica.pl/en.html

- http://cti.itc.virginia.edu/~cmg/Demo/scriptFrame.html

| ||||||||||||||||||||