Petard

A petard was a small bomb used to blow up gates and walls when breaching fortifications, of French origin and dating back to the sixteenth century.[1] A typical petard was a conical or rectangular metal object containing 2–3 kg (5 or 6 pounds) of gunpowder, with a slow match as a fuse.

Etymology

Petard comes from the Middle French peter, to break wind, from pet expulsion of intestinal gas, from the Latin peditus, past participle of pedere, to break wind, akin to the Greek bdein, to break wind (Merriam-Webster). Petard is a modern French word, meaning a firecracker (it is the basis for the word for firecracker in several other European languages).

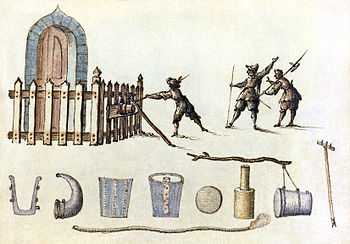

Petardiers were used during sieges of castles or fortified cities. The petard, a rather primitive and exceedingly dangerous explosive device, consisted of a brass or iron bell-shaped device filled with gunpowder fixed to a wooden base called a madrier. This was attached to a wall or gate using hooks and rings, the fuse lit and, if successful, the resulting explosive force, concentrated at the target point, would blow a hole in the obstruction, allowing assault troops to enter.

The word remains in modern usage in the phrase hoist with one's own petard, which means "to be harmed by one's own plan to harm someone else" or "to fall into one's own trap," implying that one could be lifted up (hoist, or blown upward) by one's own bomb.

Overview

Petards were often placed either inside tunnels under walls, or directly upon gates. The petard's shape allows the concussive pressure of the blast to be applied entirely towards the destruction of the gate. Depending on design, a petard could be secured by propping it against the gate using beams as illustrated, or nailing it in place on a madrier, a thick wooden board fixed to the end of the petard in advance.[2]

Variants

A petard mortar was the demolition weapon fitted to the Churchill AVRE tank. It was a mortar of a 290 mm bore, known to its crews as the "flying dustbin" due to the characteristics of its projectile, an unaerodynamic 20 kg charge that could be fired up to 100 m. This was sufficient to demolish many bunkers and earthworks and even disable a Tiger tank.[citation needed]

In Maltese English, home-made fireworks are called petards (the Maltese word murtal is related to "mortar"). Petards are detonated by the dozen during feasts dedicated to local patron saints.[citation needed]

"Hoist with his own petard"

If a petard detonated prematurely, the petardier would be lifted by the explosion. In addition, the usual human response is to get away from trouble by the most direct means possible, but a straight line is rarely the safest route of departure while under fire, and this is particularly true after setting a petard. The backblast went straight back from the fortification: if the petardier also moved straight back he would be "hoist by his own petard".[citation needed]

William Shakespeare used "hoist with his own petard" in Hamlet, in which the word "hoist" is the (now archaic) past participle of the earlier form "hoise" for the verb "hoist".[3][4]

In the following passage, the "letters" refer to instructions written by his uncle Claudius, the King, to be carried sealed to the King of England, by Hamlet, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the latter being two schoolfellows of Hamlet. The letters, as Hamlet suspects, contain a death warrant for Hamlet, who later opens and modifies them to refer to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Enginer refers to a military engineer, the spelling reflecting Elizabethan stress.

- There's letters seal'd: and my two schoolfellows,

- Whom I will trust as I will adders fang'd,

- They bear the mandate; they must sweep my way

- And marshal me to knavery. Let it work;

- For 'tis the sport to have the enginer

- Hoist with his own petar'; and 't shall go hard

- But I will delve one yard below their mines

- And blow them at the moon: O, 'tis most sweet,

- When in one line two crafts directly meet.

After modifying the letters, Hamlet escapes the ship and returns to Denmark. Hamlet's actual meaning is "cause the bomb maker to be blown up with his own bomb", metaphorically turning the tables on Claudius, whose messengers are killed instead of Hamlet. Shakespeare's use of "petar" (flatulate) rather than "petard" may be an off-colour pun.[5][6]

See also

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Petard. |

References

- ↑ Dictionary.reference.com

- ↑ "Stuart Jobs". The Worst Jobs in History. Season 1. http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/W/worstjobs/stuart.html.

- ↑ Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. "hoist". Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "hoist". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ↑ "The Phrase Finder".

- ↑ Adams, Cecil (July 14, 1978). "What's a petard, as in "hoist by his own ..."?". The Straight Dope. Chicago Reader. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

External links

| Look up hoist with one's own petard in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up petard in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Media related to Petard at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Petard at Wikimedia Commons