Pertussis

| Pertussis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

A young boy coughing due to pertussis. | |

| ICD-10 | A37 |

| ICD-9 | 033 |

| DiseasesDB | 1523 |

| MedlinePlus | 001561 |

| eMedicine | emerg/394 ped/1778 |

| MeSH | D014917 |

Pertussis — commonly called whooping cough (/ˈhuːpɪŋ kɒf/ or /ˈhwuːpɪŋ kɒf/) — is a highly contagious bacterial disease caused by Bordetella pertussis. In some countries, this disease is called the 100 days' cough or cough of 100 days.[1]

Symptoms are initially mild, and then develop into severe coughing fits, which produce the namesake high-pitched "whoop" sound in infected babies and children when they inhale air after coughing.[2] The coughing stage lasts approximately six weeks before subsiding. Prevention by vaccination is of primary importance given the seriousness of the disease in children.[3] Although treatment is of little direct benefit to the person infected, antibiotics are recommended because they shorten the duration of infectiousness.[3] It is currently estimated that the disease annually affects 48.5 million people worldwide, resulting in nearly 295,000 deaths.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The classic symptoms of pertussis are a paroxysmal cough, inspiratory whoop, and fainting and/or vomiting after coughing.[5] The cough from pertussis has been documented to cause subconjunctival hemorrhages, rib fractures, urinary incontinence, hernias, post-cough fainting, and vertebral artery dissection.[5] Violent coughing can cause the pleura to rupture, leading to a pneumothorax. If there is vomiting after a coughing spell or an inspiratory whooping sound on coughing, the likelihood almost doubles that the illness is pertussis. On the other hand, the absence of a paroxysmal cough or posttussive emesis makes it almost half as likely.[5]

The incubation period is typically seven to ten days with a range of four to 21 days and rarely may be as long as 42 days,[6] after which there are usually mild respiratory symptoms, mild coughing, sneezing, or runny nose. This is known as the catarrhal stage. After one to two weeks, the coughing classically develops into uncontrollable fits, each with five to ten forceful coughs, followed by a high-pitched "whoop" sound in younger children, or a gasping sound in older children, as the patient struggles to breathe in afterwards (paroxysmal stage).

Fits can occur on their own or can be triggered by yawning, stretching, laughing, eating or yelling; they usually occur in groups, with multiple episodes every hour around the clock. This stage usually lasts two to eight weeks, or sometimes longer. A gradual transition then occurs to the convalescent stage, which usually lasts one to two weeks. This stage is marked by a decrease in paroxysms of coughing, both in frequency and severity, and a cessation of vomiting. A tendency to produce the "whooping" sound after coughing may remain for a considerable period after the disease itself has cleared up.

Diagnosis

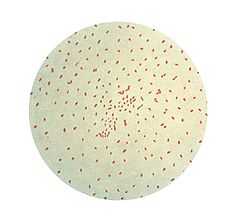

Methods used in laboratory diagnosis include culturing of nasopharyngeal swabs on Bordet-Gengou medium, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), direct immunofluorescence (DFA), and serological methods. The bacteria can be recovered from the patient only during the first three weeks of illness, rendering culturing and DFA useless after this period, although PCR may have some limited usefulness for an additional three weeks.

For most adults and adolescents, who often do not seek medical care until several weeks into their illness, serology may be used to determine whether antibody against pertussis toxin or another component of B. pertussis is present at high levels in the blood of the patient. By this stage they have been contagious for some weeks and may have spread the infection to many people. Because of this, adults, who are not in great danger from pertussis, are increasingly being encouraged to be vaccinated.

A similar, milder disease is caused by B. parapertussis.[7]

Prevention

The primary method of prevention for pertussis is vaccination. There is insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of antibiotics in those who have been exposed but are without symptoms.[8] Prophylactic antibiotics, however, are still frequently used in those who have been exposed and are at high risk of severe disease (such as infants).[3]

Vaccine

Pertussis vaccines are effective,[9] routinely recommended by the World Health Organization[10] and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention,[11] and are estimated to have saved over half a million lives in 2002.[10] The multi-component acellular pertussis vaccine, for example, is between 71-85% effective with greater effectiveness for more severe disease.[9] Despite widespread use of the vaccine, however, pertussis has persisted in vaccinated populations and is today "one of the most prevalent vaccine-preventable diseases in Western countries."[12] The recent resurgences in pertussis infections are attributed to a combination of waning immunity and new mutations in the bacteria that existing vaccines are unable to effectively control.[13][12]

Immunization against pertussis does not confer lifelong immunity; a 2011 study by the CDC indicated that the duration of protection may only last three to six years. This covers childhood, which is the time of greatest exposure and greatest risk of death from pertussis.[5][14] For children, the immunizations are commonly given in combination with immunizations against tetanus, diphtheria, polio and haemophilus influenzae type B at ages two, four, six, and 15–18 months. A single later booster is given at four to six years of age. (US schedule). In the UK, pertussis vaccinations are given at 2, 3 and 4 months, with a pre-school booster at 3 years 4 months.

Dr. Paul Offit, chief of the Director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, comments that the last pertussis vaccination people receive may be their booster at age 11 or 12 years old. However, he states that it is important for adults to have immunity as well to prevent transmission of the disease to infants.[15] While adults rarely die if they contract pertussis after the effects of their childhood vaccinations have worn off, they may transmit the disease to people at much higher risk of injury or death. To reduce morbidity and spread of the disease, Canada, France, the U.S. and Germany have approved pertussis vaccine booster shots. In 2012, a federal advisory panel recommended that all U.S. adults receive vaccination.[16] Later that year, health officials in the UK recommended the vaccination of pregnant women (between 28 – 38 weeks of pregnancy) in order to protect their unborn children. Designed to protect babies from birth until their first standard vaccination at eight weeks of age, this vaccine was introduced in response to the ongoing outbreak of pertussis in the UK, the worst in over a decade.[17]

The pertussis booster for adults is combined with a tetanus vaccine and diphtheria vaccine booster; this combination is abbreviated "Tdap" (Tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis). It is similar to the childhood vaccine called "DTaP" (Diphtheria, Tetanus, acellular Pertussis), with the main difference that the adult version contains smaller amounts of the diphtheria and pertussis components — this is indicated in the name by the use of lower-case "d" and "p" for the adult vaccine. The lower-case "a" in each vaccine indicates that the pertussis component is acellular, or cell-free, which improves safety by dramatically reducing the incidence of side effects. Adults should request the Tdap instead of just a tetanus vaccination in order to receive the multi-vaccine. The pertussis component of the original DPT vaccine accounted for most of the minor local and systemic side effects in many vaccinated infants (such as mild fever or soreness at the injection site). The newer acellular vaccine, known as DTaP, has greatly reduced the incidence of adverse effects compared to the earlier "whole-cell" pertussis vaccine, however the efficacy of the acellular vaccine declines faster than the whole-cell vaccine.[18][19]

Infection with pertussis induces incomplete natural immunity that wanes over time.[20] Natural immunity lasts longer than vaccine-induced immunity, with one study reporting maximum effectiveness as long as 20 years in the former and 12 in the latter.[21] Vaccination exemption laws appear to result in increased cases.[22][23]

Management

People with pertussis are infectious from the beginning of the catarrhal stage (runny nose, sneezing, low-grade fever, symptoms of the common cold) through the third week after the onset of paroxysms (multiple, rapid coughs) or until 5 days after the start of effective antimicrobial treatment.

A reasonable guideline is to treat people age >1 year within 3 weeks of cough onset and infants age <1 year and pregnant women (especially near-term) within 6 weeks of cough onset. If the patient is diagnosed late, antibiotics will not alter the course of the illness and, even without antibiotics, the patient should no longer be spreading pertussis.[3] Antibiotics decrease the duration of infectiousness and thus prevent spread.[3]

The antibiotic erythromycin or azithromycin is a front-line treatment[8] Newer macrolides are frequently recommended due to lower rates of side effects.[3] Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) may be used in those with allergies to first-line agents or in infants who have a risk of pyloric stenosis from macrolides.[3] Effective treatments of the cough associated with this condition have not been developed.[4]

Erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin are preferred for the treatment of pertussis in persons ≥1 month of age.

Prognosis

Common complications of the disease include pneumonia, encephalopathy, earache, or seizures.

Most healthy older children and adults will have a full recovery from pertussis, however those with comorbid conditions can have a higher risk of morbidity and mortality.

Infection in newborns is particularly severe. Pertussis is fatal in an estimated 1.6% of hospitalized infants who are under one year of age.[24] Infants under one are also more likely to develop complications, such as: pneumonia (20%), encephalopathy (0.3%), seizures (1%), failure to thrive, and death (1%)[24] — perhaps due to the ability of the bacterium to suppress immune response against it.[25] Pertussis can cause severe paroxysm-induced cerebral hypoxia and 50% of infants admitted to hospital will suffer apneas.[24] Reported fatalities from pertussis in infants have increased substantially over the past 20 years.[26]

Epidemiology

Worldwide, whooping cough affects 48.5 million people yearly.[4] As of 2010 it caused about 81,000 deaths, down from 167,000 in 1990.[27] This is despite generally high coverage with the DTP and DTaP vaccines. Pertussis is one of the leading causes of vaccine-preventable deaths world-wide.[28] 90% of all cases occur in developing countries.[28]

Before vaccines, an average of 178,171 cases were reported in the U.S., with peaks reported every two to five years; more than 93% of reported cases occurred in children under 10 years of age. The actual incidence was likely much higher. After vaccinations were introduced in the 1940s, incidence fell dramatically to less than 1,000 by 1976. Incidence rates have increased since 1980. In 2012, rates in the United States reached a high of 41,880 people; this is the highest it has been since 1955 when numbers reached 62,786.[29]

Pertussis is the only vaccine-preventable disease that is associated with increasing deaths in the U.S. The number of deaths increased from four in 1996 to 17 in 2001, almost all of which were infants under one year.[30] In Canada, the number of pertussis infections has varied between 2,000 and 10,000 reported cases each year over the last ten years.[31]

Australia reports an average of 10,000 cases a year, but the number of cases has increased in recent years.[32] In the U.S. pertussis in adults has increased significantly since about 2004.[33]

Outbreaks in the U.S.

- 2010

In 2010 ten infants in California died and health authorities declared an epidemic with 9,120 cases.[34][35] Investigating the cases of the ten infant fatalities, it found that doctors had been misdiagnosing the infants' condition despite having seen infants on multiple visits.[36] Statistical analysis identified significant overlap in communities with cluster of nonmedical exemptions for children and cases of whooping cough. The study found the number of exemption varies widely among communities but tends to be highly clustered, in some schools more than ¾ of parents filed for exemptions not to vaccinate their children. The data suggest vaccine refusal based on nonmedical reason and personal belief may have been one of several factors, in addition to less long lasting effect of the current vaccine and most vaccinated adults and older children have not received a booster shot, contributed to the California outbreak in 2010.[37][38]

- 2012

In April and May 2012, pertussis was declared to be at epidemic levels in the US state of Washington with 3,308 cases by December.[39][40][41] In December 2012, the state of Vermont declared a pertussis epidemic with 522 cases.[42] The state of Wisconsin has the highest incidence rate, with 3,877 cases of whooping cough, however it did not release an official epidemic declaration.[41]

History

B. pertussis was isolated in pure culture in 1906 by Jules Bordet and Octave Gengou, who also developed the first serology and vaccine. Efforts to develop an inactivated whole-cell pertussis vaccine began soon after B. pertussis was grown in pure culture in 1906. In the 1920s, Dr. Louis W. Sauer developed a vaccine for whooping cough at Evanston Hospital (Evanston, IL). In 1925, the Danish physician Thorvald Madsen was the first to test a whole-cell pertussis vaccine on a wide scale.[43]

He used the vaccine to control outbreaks in the Faroe Islands in the North Sea. In 1942, the American scientist Pearl Kendrick combined the whole-cell pertussis vaccine with diphtheria and tetanus toxoids to generate the first DTP combination vaccine. To minimize the frequent side effects caused by the pertussis component of the vaccine, the Japanese scientist Yuji Sato developed an acellular pertussis vaccine consisting of purified haemagglutinins (HAs: filamentous strep throat and leucocytosis-promoting-factor HA), which are secreted by B. pertussis into the culture medium. Sato's acellular pertussis vaccine was used in Japan since 1981.[44] Later versions of the acellular pertussis vaccine used in other countries consisted of additional defined components of B. pertussis and were often part of the DTaP combination vaccine.

The complete B. pertussis genome of 4,086,186 base pairs was sequenced in 2004.[45]

Society and culture

Much of the controversy surrounding the DPT vaccine in the 1970s and 1980s related to the question of whether the whole-cell pertussis component caused permanent brain injury in rare cases, called pertussis vaccine encephalopathy. Despite this possibility, doctors recommended the vaccine due to the overwhelming public health benefit, because the claimed rate was very low (one case per 310,000 immunizations, or about 50 cases out of the 15 million immunizations each year in the United States), and the risk of death from the disease was high (pertussis killed thousands of Americans each year before the vaccine was introduced).[46]

No studies showed a causal connection, and later studies showed no connection of any type between administration of the DPT vaccine and permanent brain injury. The alleged vaccine-induced brain damage proved to be an unrelated condition, infantile epilepsy.[47] Eventually evidence against the hypothesized existence of pertussis vaccine encephalopathy mounted to the point that in 1990, the Journal of American Medical Association called it a "myth" and "nonsense".[48]

However, before that point, criticism of the studies showing no connection and a few well-publicized anecdotal reports of permanent disability that were blamed on the DPT vaccine gave rise to anti-DPT movements in the 1970s.[49] The negative publicity and fear-mongering caused the immunization rate to fall in several countries, including the UK, Sweden, and Japan. In many cases, a dramatic increase in the incidence of pertussis followed.[50]

Unscientific claims about the vaccine pushed suppliers of the vaccines out of the market.[46] In the United States, low profit margins and an increase in vaccine-related lawsuits led many manufacturers to stop producing the DPT vaccine by the early 1980s.[46]

In 1982, the television documentary "DPT: Vaccine Roulette" depicted the lives of children whose severe disabilities were inaccurately blamed on the DPT vaccine by reporter Lea Thompson.[51] The negative publicity generated by the documentary led to a tremendous increase in the number of lawsuits filed against vaccine manufacturers.[52] By 1985, manufacturers of vaccines had difficulty obtaining liability insurance. The price of the DPT vaccine skyrocketed, leading to shortages around the country. Only one manufacturer of the DPT vaccine remained in the U.S. by the end of 1985. To avert a vaccine crisis, Congress in 1986 passed the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act (NCVIA), which established a federal no-fault system to compensate victims of injury caused by mandated vaccines.[53] The majority of claims that have been filed through the NCVIA have been related to injuries allegedly caused by the whole-cell DPT vaccine.

The concerns about side effects led Yuji Sato to introduce an even safer acellular version of the pertussis vaccine for Japan in 1981. The acellular pertussis vaccine was approved in the United States in 1992 for use in the combination DTaP vaccine. Research has shown that the acellular vaccine has a rate of adverse events similar to that of a Td vaccine (a tetanus-diphtheria vaccine containing no pertussis vaccine).[54]

References

- ↑ Carbonetti NH (June 2007). "Immunomodulation in the pathogenesis of Bordetella pertussis infection and disease". Curr Opin Pharmacol 7 (3): 272–8. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2006.12.004. PMID 17418639.

- ↑ Symptoms, sounds, and a video WhoopingCough.net

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Heininger, U (February 2010). "Update on pertussis in children.". Expert review of anti-infective therapy 8 (2): 163–73. doi:10.1586/eri.09.124. PMID 20109046.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Bettiol S, Wang K, Thompson MJ, et al. (2012). "Symptomatic treatment of the cough in whooping cough". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (5): CD003257. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003257.pub4. PMID 22592689.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Cornia PB, Hersh AL, Lipsky BA, Newman TB, Gonzales R (August 2010). "Does this coughing adolescent or adult patient have pertussis?". JAMA 304 (8): 890–6. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1181. PMID 20736473.

- ↑ Pertussis (whooping cough), New York State Department of Health, Updated: January 2012, retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ↑ Finger H, von Koenig CHW (1996). Bordetella–Clinical Manifestations. In: Barron's Medical Microbiology (Barron S et al., eds.) (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Altunaiji, S; Kukuruzovic, R, Curtis, N, Massie, J (2007-07-18). "Antibiotics for whooping cough (pertussis).". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD004404. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004404.pub3. PMID 17636756.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Zhang L, Prietsch SOM, Axelsson I, Halperin SA (2012). "Acellular vaccines for preventing whooping cough in children". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001478. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001478.pub5. PMID 22419280.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Annex 6 whole cell pertussis". World Health Organization. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ↑ "Pertussis: Summary of Vaccine Recommendations". Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Mooi et. al. (Feb 2013). "Pertussis resurgence: waning immunity and pathogen adaptation - two sides of the same coin.". Epidemiology and Infection (Oxford University Press): 1–10. doi:10.1017/S0950268813000071.

- ↑ van der Ark et. al. (Sep 2012). "Resurgence of pertussis calls for re-evaluation of pertussis animal models.". Expert Reviews 11 (9). doi:10.1586/erv.12.83.

- ↑ Versteegh FGA, Schellekens JFP, Fleer A, Roord JJ. (2005). "Pertussis: a concise historical review including diagnosis, incidence, clinical manifestations and the role of treatment and vaccination in management.". Rev Med Microbiol 16 (3): 79–89.

- ↑ Rettner, Rachael. "Whooping Cough Vaccine Protection Fades After 3 Years". My Health News Daily. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ http://apnews.myway.com/article/20120222/D9T2I3JG4.html

- ↑ "BBC News - Whooping cough outbreak: Pregnant women to be vaccinated".

- ↑ "Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid and Acellular Pertussis Vaccine Adsorbed, ADACEL, Aventis Pasteur Ltd". Archived from the original on 2007-02-16. Retrieved 2006-05-01.

- ↑ Allen, A. (2013). "The Pertussis Paradox". Science 341 (6145): 454–455. doi:10.1126/science.341.6145.454.

- ↑ Disease Control Priorities Project. (2006). Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (Table 20.1, page 390 ). International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, World Bank. Washington DC (www.worldbank.org).

- ↑ Wendelboe, Aaron; Van Rie, Annelies; Salmaso, Stefania; Englund, Janet (May 2005). "Duration of Immunity Against Pertussis After Natural Infection or Vaccination". Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 24 (5): S58–S61. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ "States with higher pertussis rates may be related to nonmedical exemptions from school vaccinations". Healio. 19 January 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ↑ Yang, Y. Tony; Debold, Vicky (February 2014). "A Longitudinal Analysis of the Effect of Nonmedical Exemption Law and Vaccine Uptake on Vaccine-Targeted Disease Rates". American Journal of Public Health 104 (2): 371–377. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301538.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "Pertussis: Complications". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ Carbonetti, Nicholas H (March 2010). "Pertussis toxin and adenylate cyclase toxin: key virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis and cell biology tools". Future Microbiol. 5: 455–469. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ↑ Guinto-Ocampo, Hazel; Bryon K McNeil, Stephen C Aronoff (April 27, 2010). "Pertussis: Follow-up". Emedicine (WebMD). Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ↑ Lozano, R (Dec 15, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.". Lancet 380 (9859): 2095–128. PMID 23245604.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Pertussis in Other Countries". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting/cases-by-year.html

- ↑ Gregory DS (2006). "Pertussis: a disease affecting all ages". Am Fam Physician 74 (3): 420–6. PMID 16913160.

- ↑ Whooping Cough - Causes, Symptoms, Treatment, Diagnosis - - C-Health

- ↑ Lavelle P (January 20, 2009). "A bad year for whooping cough". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ↑ Kate Murphy. "Enduring and Painful, Pertussis Leaps Back". The New York Times. 22 February 2005.

- ↑ Miriam Falco (October 20, 2010). "Ten infants dead in California whooping cough outbreak". CNN. Retrieved 2010-10-21. "Whooping cough, also known as pertussis, has claimed the 10th victim in California, in what health officials are calling the worst outbreak in 60 years."

- ↑ "Pertussis (Whooping Cough) Outbreaks". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). January 11, 2011.

- ↑ Rong-Gong Lin II (September 7, 2010). "Diagnoses lagged in baby deaths". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-09-08.

- ↑ Shute, Nancy (30 September 2013). "Vaccine Refusuals Fueled California’s Whooping Cough Epidemic". NPR. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ↑ Atwell, Jessica; Van Otterloo, Josh; Zipprich, Jennifer; Winter, Kathleen; Harriman, Kathleen; Salmon, Daniel; Halsey, Neal; Omer, Saad (2013). "Nonmedical Vaccine Exemptions and Pertussis in California, 2010". Pediatrics (American Academy of Pediatrics) 132 (4): 624–630. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0878.

- ↑ Donna Gordon Blankinship (May 10, 2012). "Whooping cough epidemic declared in Wash. state". Associated Press, Seattle Times. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ↑ Washington State Department of Health (April 2012). "Whooping cough cases reach epidemic levels in much of Washington". Washington State Department of Health. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Karen Herzog (Aug 17, 2012). "Wisconsin has highest rate of whooping cough". the Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ Johnson, T. (December 13, 2012). "Whooping cough epidemic declared in Vermont". Burlington Free Press. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ↑ Baker JP, Katz SL (2004). "Childhood vaccine development: an overview". Pediatr. Res. 55 (2): 347–56. doi:10.1203/01.PDR.0000106317.36875.6A. PMID 14630981.

- ↑ Sato Y, Kimura M, Fukumi H (1984). "Development of a pertussis component vaccine in Japan". Lancet 1 (8369): 122–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(84)90061-8. PMID 6140441.

- ↑ Parkhill J. et al. (2003). "Comparative analysisof the genome sequences of Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica". Nat Genet 35 (1): 32–40.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Huber, Peter (July 8, 1991). "Junk Science in the Courtroom". Forbes. p. 68.

- ↑ Cherry, James D. (March 2007). "Historical Perspective on Pertussis and Use of Vaccines to Prevent It: 100 years of pertussis (the cough of 100 days)". Microbe Magazine.

- ↑ Cherry JD (1990). "'Pertussis vaccine encephalopathy': it is time to recognize it as the myth that it is". JAMA 263 (12): 1679–80. doi:10.1001/jama.263.12.1679. PMID 2308206.

- ↑ Geier D, Geier M (2002). "The true story of pertussis vaccination: a sordid legacy?". Journal of the history of medicine and allied sciences 57 (3): 249–84. doi:10.1093/jhmas/57.3.249. PMID 12211972.

- ↑ Gangarosa EJ, Galazka AM, Wolfe CR, Phillips LM, Gangarosa RE, Miller E, Chen RT (1998). "Impact of anti-vaccine movements on pertussis control: the untold story". Lancet 351 (9099): 356–61. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04334-1. PMID 9652634.

- ↑ Rachel K. Sobel (22 May 2011). "At last: Ignorance inoculation". Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ↑ Evans G (2006). "Update on vaccine liability in the United States: presentation at the National Vaccine Program Office Workshop on strengthening the supply of routinely recommended vaccines in the United States, 12 February 2002". Clin. Infect. Dis. 42 Suppl 3: S130–7. doi:10.1086/499592. PMID 16447135.

- ↑ Smith MH (1988). "National Childhood Vaccine Injury Compensation Act". Pediatrics 82 (2): 264–9. PMID 3399300.

- ↑ Pichichero ME, Rennels MB, Edwards KM, et al. (June 2005). "Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and 5-component pertussis vaccine for use in adolescents and adults". JAMA 293 (24): 3003–11. doi:10.1001/jama.293.24.3003. PMID 15933223.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pertussis. |

- Pertussis at Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology

- View personal stories of pertussis – ShotbyShot.org, California Immunization Coalition (CIC)

- Whooping cough information page – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment